Contents

Who’s the Boss?

No I in Team?

Credible Sources

Vibes and Pressures

The pace of curricular change in American classrooms is typically sluggish, slinking unevenly across an archipelago of school boards, district officials, and classroom teachers. Even when an initiative can traverse the layers of policymaking that run from national priorities to local bureaucracies, reform has the chronic tendency, as one historian puts it, to “bounce off the classroom door.”1 The global rise of more ambitious administrative approaches to assessment and accountability since the 1990s has sent educational researchers into the field to discover (and sometimes to shape) how policy decisions most effectively transmit through the system.2 Scholars pose a range of questions. Do standards do anything at all? How do teachers comprehend what they’re obligated to do versus what they can ignore? Are social studies teachers classic “street-level bureaucrats” with mostly discretionary authority over instruction, or can they be ordered, encouraged, nudged, teamed up, or disciplined into aligning their practice with a scripted administrative vision?3 What conditions make social studies teachers (and US history content in particular) more or less susceptible to managerial directives? Contemporary culture warriors (and much of the media coverage that attends to them) tend to leave these questions offscreen, but they are fundamental to judging whether the efforts of education reformers and curricular activists even have a shot at succeeding or if they are, as some of our teacher interviewees described them, “rushed and trendy.”4

Who’s the Boss?

In the typical organizational chart for a superintendent’s office or school administration, structures of authority and chains of command may seem clear-cut. When it comes to curriculum, however, local conditions are far more complicated. Long-standing traditions of teacher autonomy over their classrooms collide with more recent efforts by state and local agency officials to standardize, synchronize, and align instruction to state standards. The daily work associated with these initiatives within local school districts and state agencies is often performed by staffers known as curriculum specialists or instructional coordinators. National education surveys since the turn of the 21st century show a clear trend of increasing administrative staffing in curriculum across all areas of instruction. Since 2000, the number of instructional coordinators working in public school districts and state education agencies has increased by 155 percent (from 39,433 in fall 2000 to 100,715 in fall 2022). Over that same period, teacher staffing increased by only 9 percent. Current national average ratios of teacher to instructional coordinators come in at 32 teachers per coordinator.5

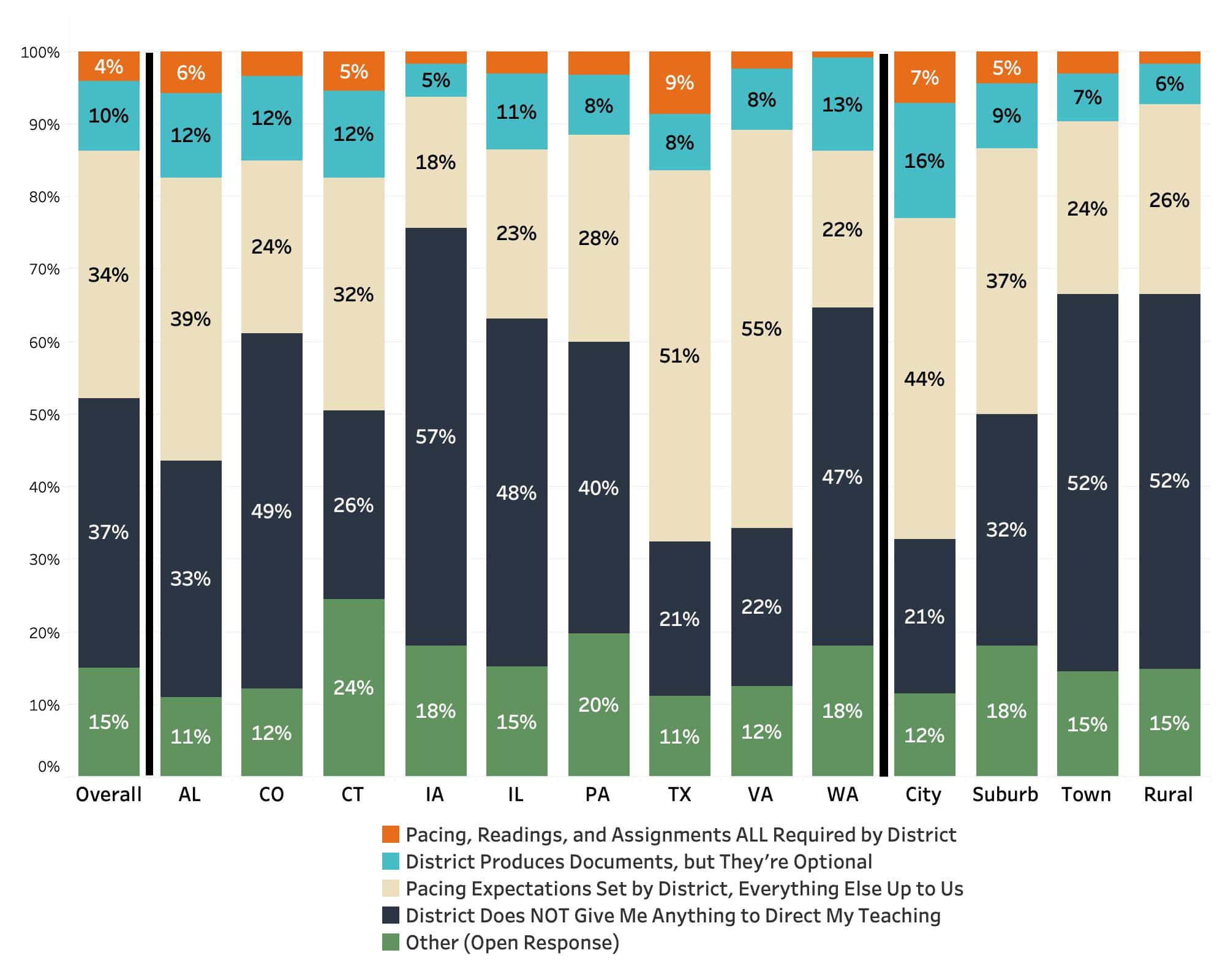

A low priority in terms of assessed subjects, social studies is less likely to receive managerial attention than mathematics and language arts. When districts do designate curricular or instructional staffing in social studies, the role varies significantly in terms of how much authority and direction they provide. Direction from district administrators, when present, generally focuses on the broad outline of the US history course. Only 4 percent of surveyed teachers said that the district requires anything more than pacing, and 37 percent of teachers said that they don’t receive anything at all from their district that directs their teaching (Fig. 15).6

Fig. 15: Curricular Direction Teachers Receive from Their District, Overall, by State, and by Locale Type (n = 2,805)

The role of the district administrator varies by locale type. In both rural and town districts, the number of teachers with no district paperwork jumps to 52 percent. Meanwhile, only 32 percent of suburban teachers and 21 percent of city teachers said the same thing (Fig. 15). Larger and better-resourced districts are more likely to have a heavier bureaucracy and, in some cases, an ambition for more top-down control—evidenced by slightly higher rates of reported district requirements among city teachers. Within these larger districts, administrators expressed a range of how much control they wield. An administrator in a well-resourced, mid-sized suburban district can be led to believe that they have the capacity, vision, and duty to align all their teachers to a single curricular document.7 In larger urban or suburban districts, there may be central office personnel, but there are also lower expectations (at least among more seasoned and realistic administrators) of alignment and uniformity throughout the system.8 On their power, urban and suburban administrators had the following to say:

- “My position has no authoritative power.” (Washington)9

- “Central office doesn’t really give guidance. . . . Nothing is required. The assessments are not required. They are all suggested.” (Illinois)10

- “Teachers rebelled at attempt to make unit plans. Some teachers ask for assistance, but mostly teachers did not want to be told ‘how to teach.’” (Alabama)11

- “[I’m] less confident that the older high school teachers are following along.” (Virginia)12

- “[I] can’t speak to what’s actually happening on the ground . . . Lots of siloed work happening.” (Illinois)13

At the school level, teacher perceptions of curricular authority also varied across locale type. Sixty-six percent of town and rural teachers said a principal had a role in directing their curriculum, compared with 56 percent of suburban teachers and 55 percent of urban teachers.14 Suburban and urban teachers reported slightly more emphasis on course teams in curricular decision-making. Seventy percent of town and 65 percent of rural teachers described their course team as influential in their own teaching, whereas 87 percent of suburban and 82 percent of urban teachers said the same.15

Administrators rarely take a one-size fits all approach to directing teachers, focusing their efforts on newer and less experienced teachers, with an understanding that longer-tenured teachers might be less receptive to their work. As one Texas coordinator put it, he and his team of instructional coaches “have newer struggling teachers that they work with more on a regular basis.”16

Administrators navigate both the structural limits of their position and the interpersonal dynamics of the workplace. In many cases, a district-level curriculum coordinator will oversee multiple subject areas, have no background in history, and work “more closely with English,” as one teacher explained.17 On the other hand, if the administrator had worked previously as a history teacher, their teachers tend to trust them more. In Colorado and Washington, curriculum coordinators are hired as Teachers on Special Assignment, a horizontal position that may come with collegial trust but limits their authority over other teachers. As one former Colorado specialist said of the position, “You are not anybody’s boss.”18 Given their experience and place within the team, school-level department chairs or course team leads are more likely to be valued by their peers. Chairs mainly serve as a link between the department and the principal or district curriculum office, and other teachers rely on them for their wisdom and experience. In some cases, they benefit from a small reduction in course load, but many do not. One Virginia teacher contrasted her course lead with her unfavorable view of the district office: “She’s part of my team. I listen to HER.”19 In a few wealthier districts, department chairs may be relieved of teaching duties and take a more active part in curriculum development.20 Authority over teacher alignment also depends on the strength of unions within the state or district. An Illinois administrator described “their union” rather than “the teachers” as the reason he cannot require a common assessment for each unit.21 Likewise, in Washington, another administrator cited union rules as a limitation on “what can be asked of [teachers]” during course team meeting time, adding that she could attend meetings only at the invitation of the team.22 In these contexts, coordinators may have a better sense of what they cannot do than what they can do.

The lack of clarity around administrative roles contributes to confusion. As one Virginia teacher marveled, “It’s a mystery to us how they fill their entire year.”23 A Washington teacher described administration as “someone up in a cubicle . . . rewording the requirements to justify their salary.”24 Of the multiple reformatting and alignment tasks that administrators asked for, a Pennsylvania teacher remarked, “It’s a gajillion bunch of letters and numbers that no one outside of the social studies department knows what they mean. I could write anything in my lesson plans, and no one would know the difference.”25

Teachers express a range of skepticism and appreciation for their administration. Unsurprisingly, teachers’ perceptions depend on who fills the role, warming up to one coordinator more than another—though the same could be said about how curriculum coordinators view their teachers. Speaking of the administration more broadly, teachers appreciate when they receive affirmation. As an Illinois teacher put it, “I seek out my administrators for advice when I need it regarding my lessons and units. They enjoy what and how I teach my lessons [and] are always willing to support me.”26

While standardized assessment may be the exception rather than the rule for social studies, three decades of accountability initiatives have nonetheless left their mark on the management of social studies teachers. Large districts tend to grow heavier bureaucracies, and in some cases, an ambition for more top-down control. Veteran teachers report a clear trend away from autonomy and idiosyncrasy and toward course team alignment and common assessment over the course of their careers.27 Commenting on the decrease in teacher autonomy, one Pennsylvania administrator admitted that, while he saw the value of oversight and alignment, “as a teacher, I would have hated it.”28

Even as state agencies, curriculum coordinators, and school principals have sought to synchronize and discipline instruction, many administrators confessed that history teachers, especially at the high school level, feel at liberty to resist directives that they find burdensome or intrusive. In some districts, administrators feel “confident” that teachers “are following the curriculum,” but they will also admit that they have “no authoritative power” and often “can’t speak to what’s actually happening on the ground,” especially in larger districts.29 Union rules certainly enhance teachers’ confidence in pushing back, but even in right-to-work states, teachers will resist increasing directives. When one Alabama administrator attempted to go beyond pacing guides and create unit plans, “teachers rebelled” because they “did not want to be told how to teach.”30 A Texas teacher who considered himself a “Lone Ranger” boasted that he could fend off administrators’ “new fandango stuff” by pointing to his students’ performance on state tests.31 The increase in alignment and oversight strikes differently across generations, with more resistance from the older teachers. As one teacher put it, there will not be as much alignment as he’d like or other “big changes” until the older teachers “retire.”32 Teachers often described a whiplash effect over the course of their careers; one administrator might assist their course team’s continual improvement with helpful resources, while the next simply pushes the latest trend, requiring paperwork rituals that teachers comply with in a perfunctory way. Ultimately, teachers ride these waves of attention and neglect, while retaining substantial discretion in deciding what they teach, how they teach it, and what materials they use.

The tug of war between administrators and teachers sometimes expresses a deeper contest over the purpose of teaching history, with sharp differences between management and labor. Among curriculum coordinators, an emphasis on developing skills of literacy, inquiry, and argumentation prevails. One veteran district administrator in Illinois recounted the “productive struggle” he had as he implemented successive rounds of reform with his teachers: backward design, literacy coaching, Socratic discussion, and thematic teaching.33 The emphasis on skills reflects profession-wide trends in curriculum and instruction and the ongoing pressures of standardized English and language arts (ELA) assessment. Administrators often express frustration with teachers focused on content rather than skills. Meanwhile, teachers typically define their expertise in terms of knowing their content. The clash may be especially pronounced if the administrator lacks a social studies background. As one Connecticut administrator complained, he would prefer a focus on “transferable history skills” but instead gets stuck working “with history teachers [who] love their content.”34 In fact, history teachers have no objections to transferable skills: almost all surveyed teachers cited critical thinking (97 percent) and informed citizenship (94 percent) as the top learning goals for their students.35 They are far less enthused, however, when they perceive that an administrator treats their social studies classes as an extra period of “nonfiction literacy” training for the next ELA exam.

Though few districts offer consistent professional development opportunities in social studies, administrators view this as an opportunity to increase teacher buy-in. A former Colorado coordinator said, “The tension was teacher autonomy and finding the best quality potential resources in front of teachers for the professional learning moments.”36 Still, districts tend to organize professional development around pedagogy and technology, leaving teachers on their own to learn new content and cultivate their historical expertise.

To the extent that a district develops curricular materials, teachers are likely to be the primary authors. In many cases, administrators organize teacher teams over the summer to create curriculum documents. Elsewhere, teachers lead the development of these documents and are invested in ensuring their fellow teachers adhere to them. A Colorado teacher recalled it being “extremely frustrating” when district and school-level administrators were not “enforcing the teaching of” the curriculum they had created.37 State authority over history education also shapes the duties assigned to curriculum coordinators. In Texas, the heavily detailed TEKS leave little room for curriculum coordinators to develop new materials, a fact reflected in district-created curriculums that were often just a reformatting or color-coding of the TEKS. But Texas administrators can insist more firmly that teachers stick to what the state and district expect them to teach. Intricate state mandates also give coordinators more opportunities for professional association, such as the state-level Texas Social Studies Supervisors Association, as well as a Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex conference where administrators work together to define their roles.38 As one Texas administrator explained, “You are never in this by yourself.”39 The Virginia Social Studies Leaders Consortium serves a similar function, bringing enterprising district-level specialists in regular contact with state agency supervisors and social studies nonprofits.40

For administrators who desire to effect broader changes across the system, networks of like-minded managers feed a shared sense of mission and a shared vocabulary. In addition to various local and regional conferences that they organize among themselves, social studies coordinators constitute a sizable and active proportion of membership in the NCSS and its associated group, the National Social Studies Leaders Association (formerly the National Social Studies Supervisors Association).

National and statewide debates about the teaching of history can shape the contest over power between teachers and administrators within the schoolhouse. The recent rise in politicized challenges aimed at the teaching of US history has become an effective tool for some administrators to encourage alignment with their expectations. As one Texas administrator put it, “Let’s teach to the TEKS and don’t get on the news. Don’t worry about CRT or the 1776 Project. We are not teaching those things.”41 Another Virginia administrator made it clear that they used the threat of “this world of controversy” to create a new set of “student-centered” materials. Teachers were told “if you want to ensure we’re on your side, always use our materials.”42

No I in Team?

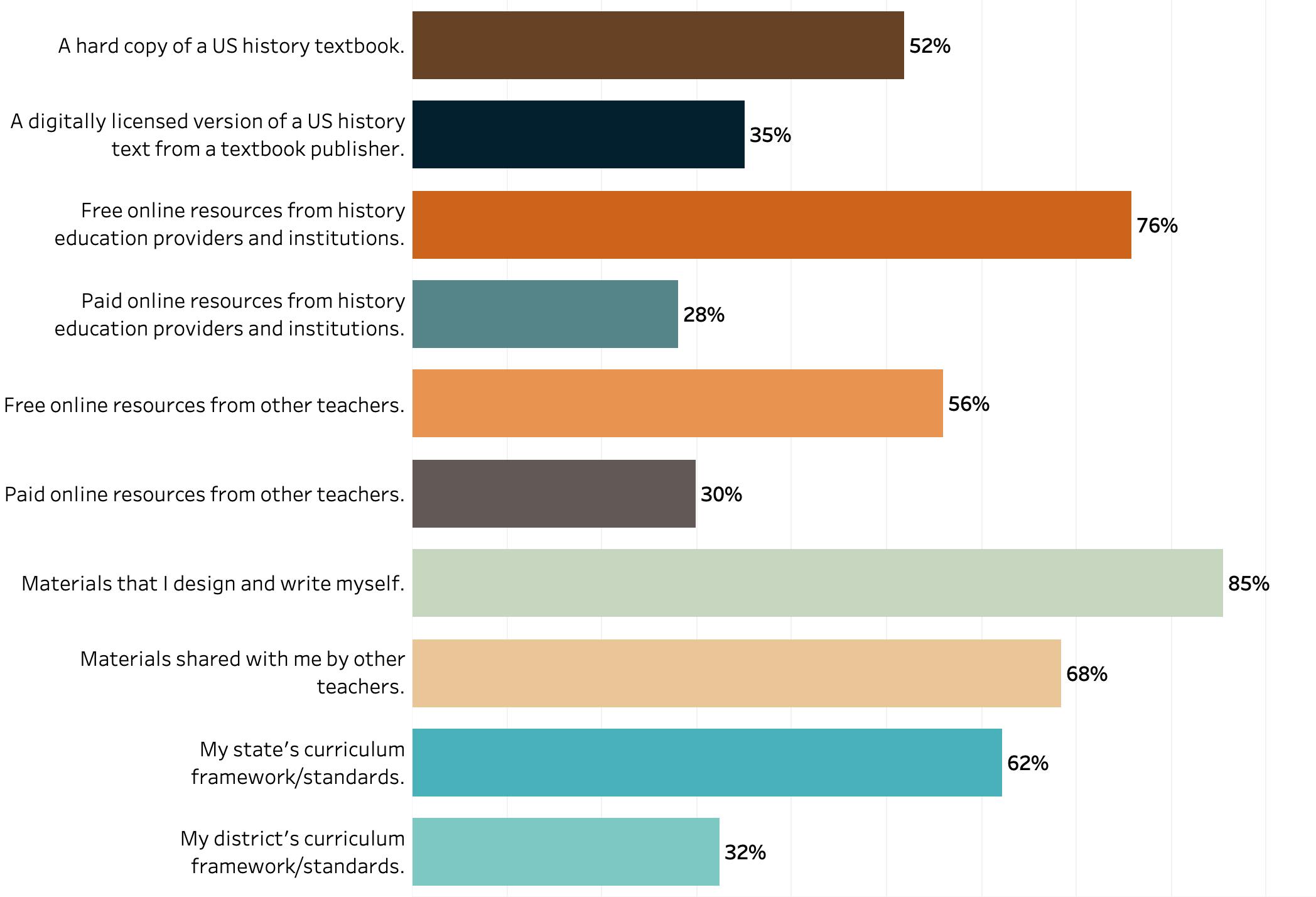

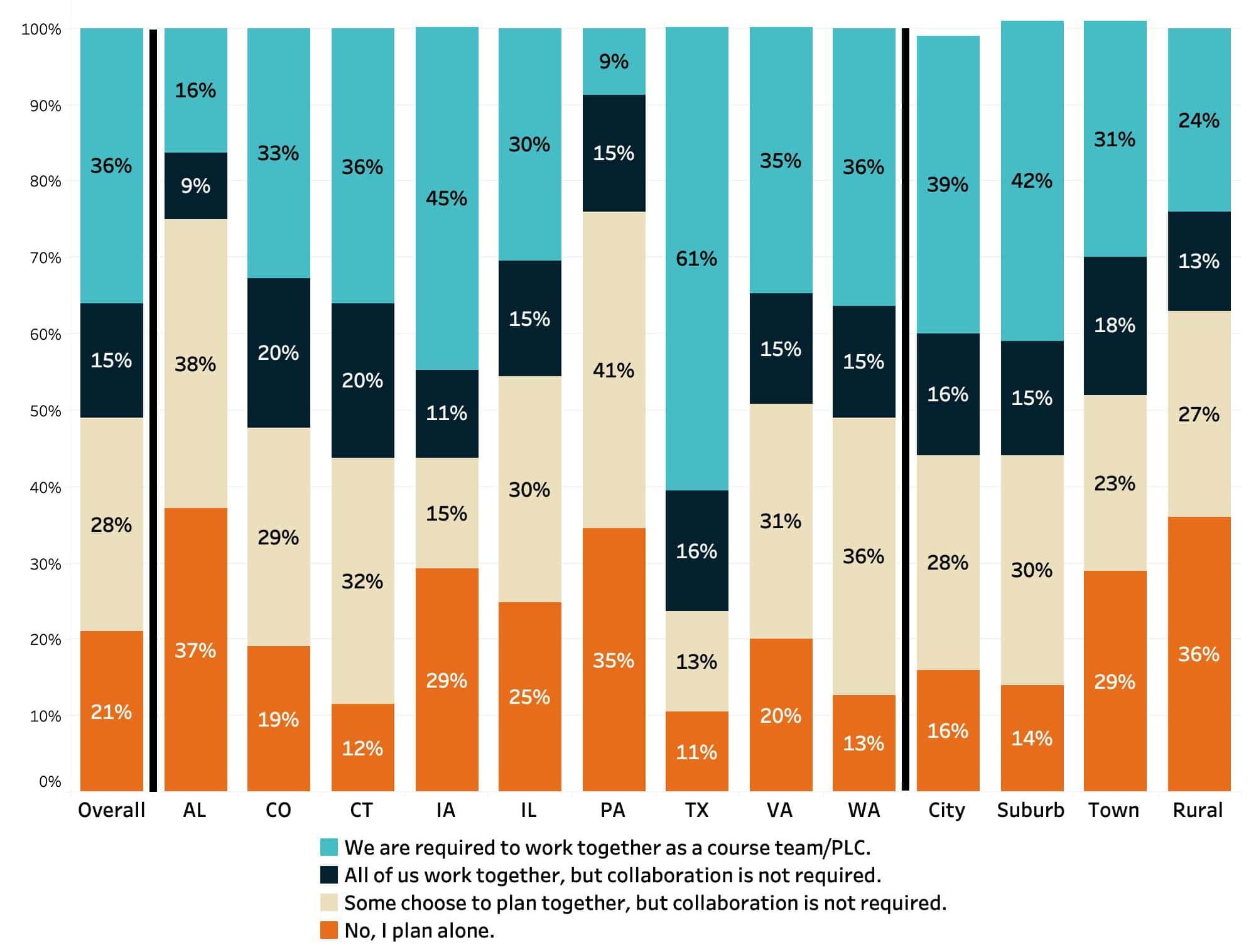

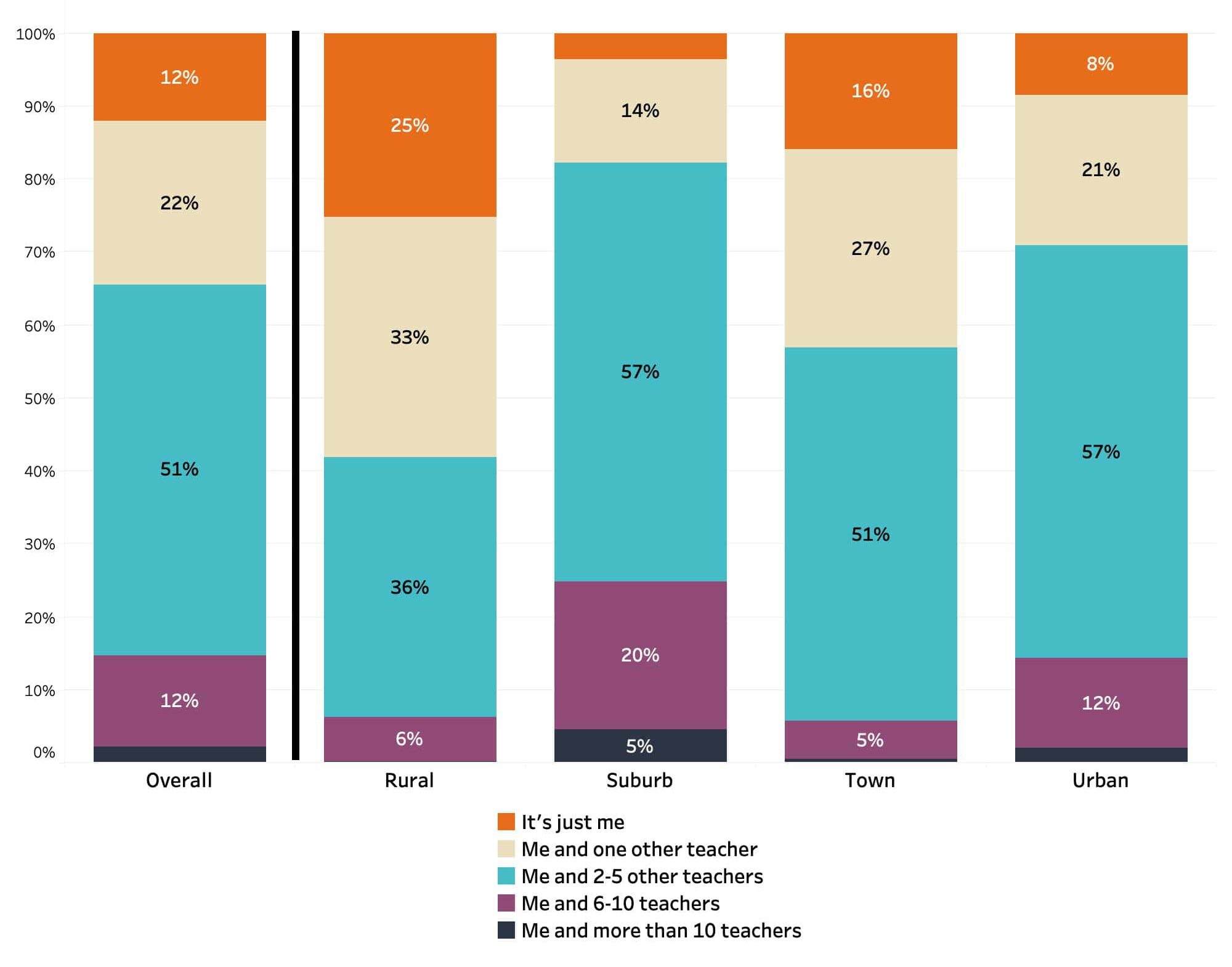

Ultimately, classroom teachers remain the decisive curricular policymakers. The “resource” most commonly referenced among surveyed teachers was “materials that I write myself” (Fig. 16). This isn’t the same as working alone. Teachers work together by choice and force. Forty-three percent of teachers described some form of voluntary collaboration and 36 percent said they were required to work together as a course team (Fig. 17).43 The professional learning community (PLC) terminology—coined by a suburban Illinois superintendent in the 1990s—is now widespread.44 Only 21 percent of surveyed teachers said they plan their lessons and curriculum alone, and most of this solitary work occurs because they are the sole US history teacher in their building.45 Thirty-four percent of teachers surveyed said that their US history team was either a solo act or a duet—a condition most common in smaller-town and rural settings (Fig. 18).46 Regardless of team size, teachers appear to rely on their colleagues more than administrators when it comes to content. When asked whose decisions matter most in terms of curriculum at the school, the top answer was the course-level team. In this sense, social studies departments function more as lesson-sharing ecosystems than structures of command and control. A Colorado teacher summed up how this process works for many teachers: “While I make the vast majority of decisions on what to teach from our state standards and how to do that, I collaborate in PLCs and with [the] administration to determine best practices.”47

Fig. 16: Teachers on What They Use to Teach US History

Fig. 17: Teachers on Collaboration (n = 3,012)

Fig. 18: How Big Is Your US History Team?

Through the survey and interviews, administrators and teachers revealed an increasing level of collaboration and alignment over the last few decades. An Illinois curriculum coordinator reflected that 16 to 17 years ago, “Teachers would fight on everything.” His teacher team would claim “you don’t trust us,” but then over time, in his view, they appreciated the value of working on a common curriculum.48 Even when the extent to which teacher teams actually align is uneven, teachers who had taught for more than 20 years described increasing cultural norms of alignment from their colleagues alongside new requirements from administrators. For some teachers, course teams can also be sites of meaningful collaboration—sometimes as a respite or a defense from administrations that they perceive as misunderstanding or devaluing social studies as compared with reading or STEM.

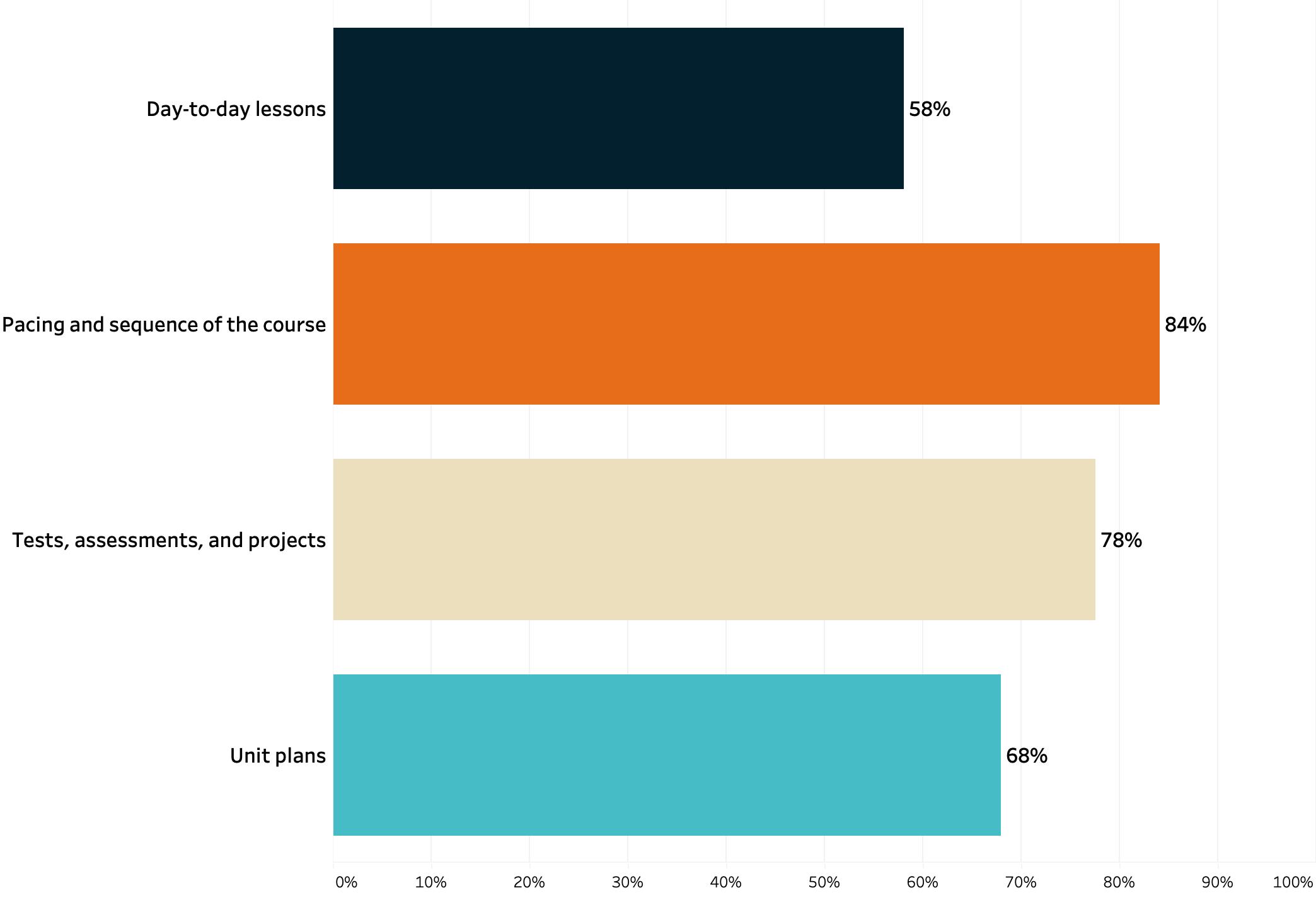

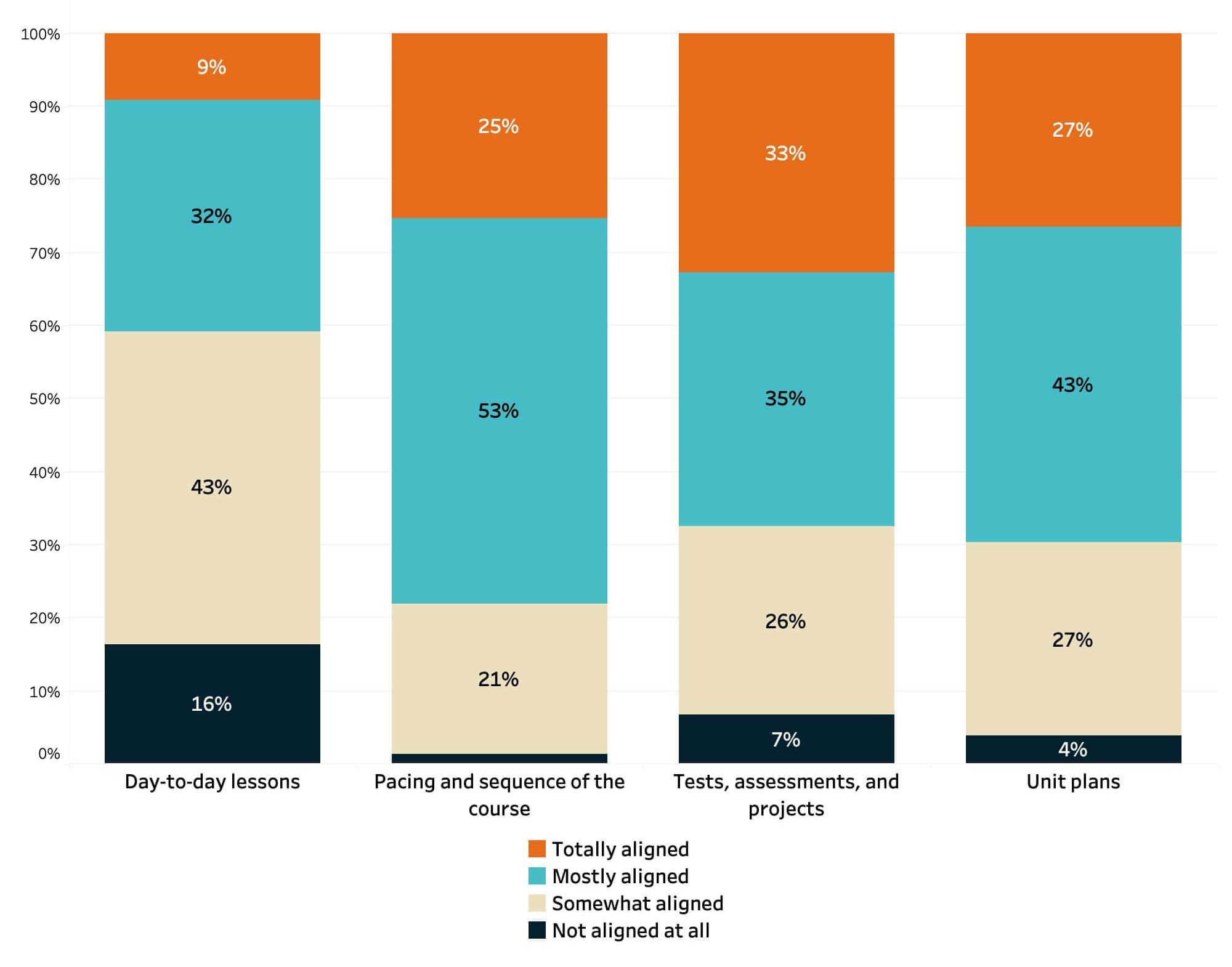

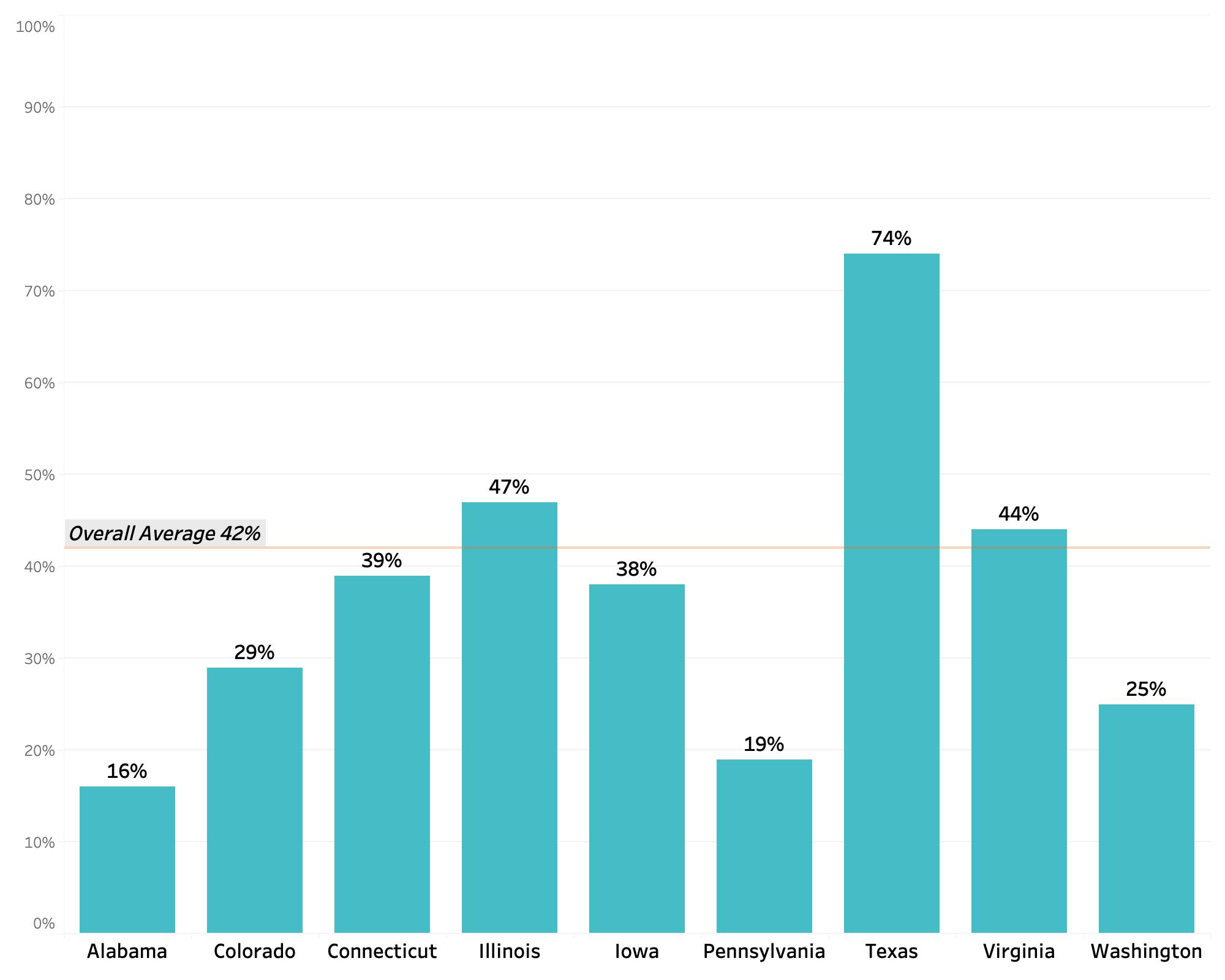

Of those who collaborate, virtually all have some measure of alignment on pacing.49 Fewer report alignment on other aspects of curriculum, but when they do, assessments and projects are more likely (78 percent of team-aligned teachers) to be held in common. Unsurprisingly, the day-to-day structure of lessons are the least aligned, with 59 percent of respondents reporting relatively or no alignment (Figs. 19 and 20).50 As some teachers expressed, their team works “off of the same unit map, but they do different activities and use different methods to get there.”51 Indeed, more alignment could even accommodate autonomy. As an Iowa teacher put it, “Our PLC has a common plan, and we genuinely follow it, but if we want to emphasize different things, we do.”52 Whether a common assessment was given every unit, every semester, or once a year, teachers used common assessments to norm themselves and gauge student achievement. The presence of a state-mandated assessment exerts a strong influence on local conditions. Texas’s annual STAAR test, for example, sustains the rationale for more alignment and more interim testing at the district and school levels. Seventy-four percent of surveyed teachers in Texas report giving a common test every unit, while only 33 percent of the other eight sample states report a similar condition (Fig. 21).

Fig. 19: Collaboration on What? (n = 1,933)

Fig. 20: How Much Alignment? (n = 1,933)

Fig. 21: Teachers Who Report Giving a Common Assessment Every Unit (n = 2,457)

Teacher perceptions about the usefulness of alignment vary by local contexts and individual preferences. One Illinois administrator described creating assessments that could “be used by any school” even if they did not use the full curriculum he recommended.53 Meanwhile, a teacher in the same district complained that a different standardized test just for the course team in his building “probably wouldn’t work very well.”54 While some teachers indicated all or most of their assessments had to be “identical,” others noted no such requirements.55 “We should probably be more aligned,” admitted one Pennsylvania teacher who gave a common midterm but no other common assessments, indicating the slow, but unmistakable trend toward alignment.56 The benefits of course team alignment are in the eye of the beholder. Teachers in Texas districts with long histories of PLC alignment seemed strikingly accustomed and unperturbed by expectations of standardization—conditions that teachers elsewhere would greet with resistance. Two teachers in the same Illinois school had very different views of their PLC; one spoke positively of her course team’s weekly collaborations, while her colleague described feeling “policed.”57

In schools where administrators see a value in maintaining common curricular documents, teachers still tend to write these materials themselves. As one Pennsylvania teacher noted, “We create the curriculum and it gets approved by central office and they look in to make sure we follow it.”58 Administrators, lacking time and background in social studies, will require a particular format for a course team’s curriculum but delegate to teacher teams what will go into them. These team documents may be “living documents” that are updated from year to year and owned by new teachers in each instance—and this is certainly understood as best practice for most administrators. But after the initial momentum, they can also sit unrevised and unevenly used in subsequent years, dated by the instructional idiosyncrasies of the teachers who happened to have worked on it in a given year.

Alignment often succeeds or fails because of personal idiosyncrasies. In several instances, interviewees mentioned that their fellow US teacher had been their student teacher and that they continued to work closely on lesson plans. In some cases, teachers reported splintered teams, with one contingent doing their own thing while another team worked together on recent trends in social studies education such as inquiry and an active classroom. As one teacher complained, some of his colleagues “were not really interested in furthering themselves as educators.”59 In rare instances, interviewed teachers described ideological differences between themselves and a colleague, feuds that they had managed for over a decade.60

On-the-job norms and mandates are not the only means by which curriculum and instruction can align across multiple school settings. Professional networks and alignment among teachers can extend beyond the school building, district, and state. District-wide professional development, although rarely organized by “job-alike” (i.e., grouped by subject) or “course-alike” (i.e., grouped by course) categories, can grant history teachers the chance to connect with colleagues during institute days at the beginning of the school year. More informally, veteran teachers who changed schools often reported maintaining contact and collaborating with former colleagues. State-level professional organizations for social studies teachers pull a small but committed number of teachers into regular contact at annual conferences. Several interviewees said they valued both the learning and the connections they made at these conferences. For teachers active on social media, the #SSchat on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) have become an important source of information and community. The AP program also has built significant networks of professional practice among teachers. As one Texas teacher enthused, the annual AP US history grading sessions are places to meet “awesome friends and collaborators” from across the country who continue to convene “on Zoom to make tests together.”61

For ambitious teachers who identify as lifelong learners and history nerds, professional development trips (offered by organizations like the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National World War II Museum, Founding Forward—formerly the Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge—with like-minded educators. Several years into her teaching career, one Iowa teacher recalled her realization that professional development supplied both a personal and professional boost: “Holy crap, this is amazing.”62 Others refrain from engaging with wider networks of social studies teachers. Some lamented their isolated state, wishing that they had the time, energy, ambition, or funding to link up with other professionals. Others seemed content to be alone with their content and their students. As one small-town Iowa teacher put it, the “weakness on my evaluations is that I don’t attend conferences, but I know that I am constantly learning and reading.”63

Credible Sources

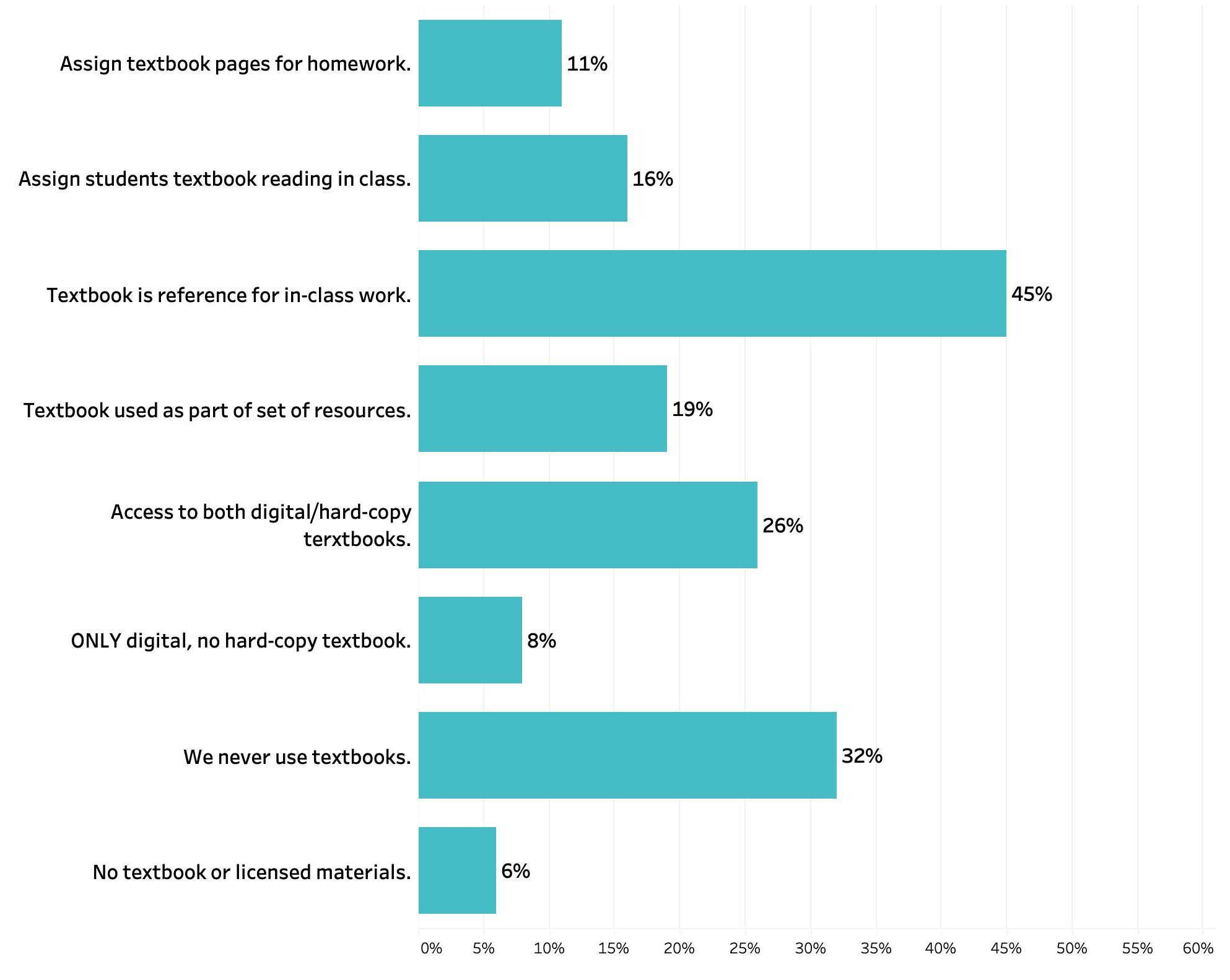

Just a few years ago, the question of what US history teachers use in their classrooms might have been answered by pointing to a short stack of textbooks from four or five publishers. Educational publishing is still a big business, but now traditional textbooks are unlikely to occupy the center of history instruction. Thirty-two percent of teachers surveyed say they never use a textbook, and those that do are far more likely to describe them as “a reference” (45 percent) than something that they expect students to read regularly in class (16 percent) or for homework (11 percent) (Fig. 22). While these trends appear consistent across locale types, usage of hard-copy textbooks varies widely from state to state, ranging from a high of 63 percent in Alabama to a low of 37 percent in Virginia. Veteran teachers remain friendlier to textbooks than newer teachers. Among veteran teachers with 21 years or more in education, 54 percent said they have copies of a textbook in their classroom, and 48 percent reported using it “as a reference for in-class work;” meanwhile, teachers with five or fewer years of experience reported rates of 42 percent and 35 percent, respectively. Conversely, 41 percent of newer teachers reported that they never use textbooks, while only 25 percent of veteran teachers reported such avoidance.64

Fig. 22: How Do You Use Your Textbook? (n = 2,361)

Notwithstanding these local and generational variances, textbooks clearly are diminishing in influence. Assumptions that century-old state-level textbook adoption rules in a couple of large states are the dog that wags the tail of curriculum nationwide is a persistent anachronism in public discourse.65 At the turn of the 21st century, 21 states, mostly in the south and west, had centralized adoption or recommendation processes.66 Today, 19 states maintain state rules for textbook adoption, but most settle somewhere between approving a lengthy list of textbooks from which districts can select or providing procedures for district textbook selection.67

Curriculum scholars might be tempted to credit the disappearance of textbooks to a long-running critique that derides textbooks as bland bargains or triumphal fables.68 But teachers offer more idiosyncratic testimony: they might prefer a book different from the one their district purchased; they might have only enough copies for a single class set; their district may have skipped over the last adoption cycle to fund a math or language arts purchase; their students may be too underprepared, distracted, or impatient to read them.69 When asked which textbook they had available, surveyed teachers most frequently responded that they could not recall the title. Those who could remember named the usual suspects: Teachers Curriculum Institute (TCI), Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt (HMH), McGraw-Hill, Pearson/Savvas, National Geographic/Cengage, and Discovery Education. Some publishers make a play for a particular state, as Five Ponds Press has in Virginia. In Alabama and Illinois, a number of teachers said they preferred to hold onto older copies of McDougall-Littell’s The Americans.70

The eclipse of textbooks reflects the rise of digital LMS and OER, and a relentless push for a “one-to-one” ratio of computing devices to students. Supplementary resources are not in themselves new; even in states with centralized adoption rules and scheduled cycles of review by local school boards (and even before the internet revolution), schools licensed “supplementary materials” on an ongoing basis and outside of approval procedures.71 Teachers’ tastes for more modular, and eventually digital materials—which district officials also found less costly—helped the case for nontextbook resources. These trends have only accelerated over the past decade, as computing technology and web access has become a policy priority, and was supercharged during COVID-19 school closures, when computer screens became the primary vehicle for instruction.72 Today, all six major textbook publishers offer digital-only licenses of their core US history titles.73

Over the past decade, concerns among state agency officials about the uneven rigor and patchwork quality of local instructional materials has spurred a movement to reassert a state role as gatekeeper and curator in the marketplace. Among state and local education agency officials and education researchers, terms like “high-quality instructional materials” (HQIM), “guaranteed and viable curriculum”(GVC), and “instructional system coherence” express administrators’ various ambitions for a tighter grip on the curricular steering wheel.74 Drawing on initiatives undertaken by Louisiana’s Department of Education in the early 2010s—where the state contracted reviewers to produce tiered ratings reports on common math and English textbooks—committees within the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and Chiefs for Change undertook an effort to spread the model beginning in 2017. The CCSSO’s Instructional Materials and Professional Development Network (IMPD) now includes 13 states, supplying research and talking points to boost state agencies’ clout as arbiters of instructional content, with recent initiatives specifically aimed at social studies.75 As one advocacy brief argues, “The level of control that a state has over curriculum decisions matters less than a state’s willingness to play an active role.”76 Leveraging connections between research nonprofits and professional networks, a few states are now experimenting with state-level review tools for social studies materials.77

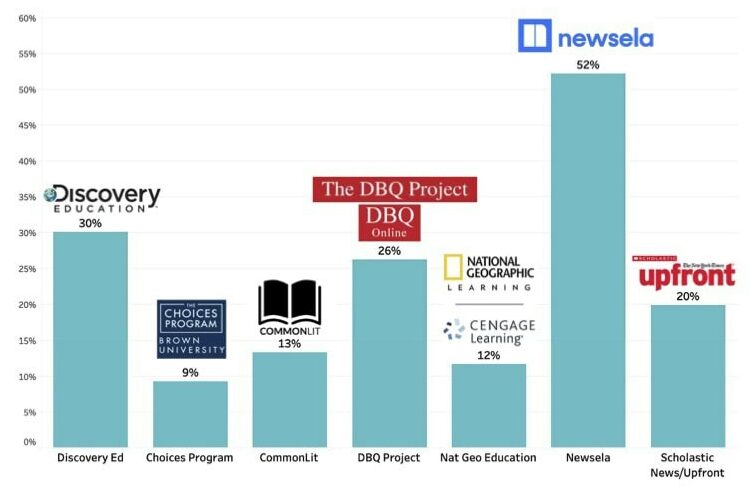

Edtech startups and nonprofits now elbow in alongside legacy publishing houses for curricular provision. In addition to a flock of catch-all tech tools with lighthearted names (BrainPop, Edpuzzle, Quizizz, Nearpod, Kahoot, and Peardeck), our survey data registered clear favorites among paid and licensed social studies resources (Fig. 23).78

Fig. 23: Reported Teacher Access to Selected Paid Resources (n = 1,677)

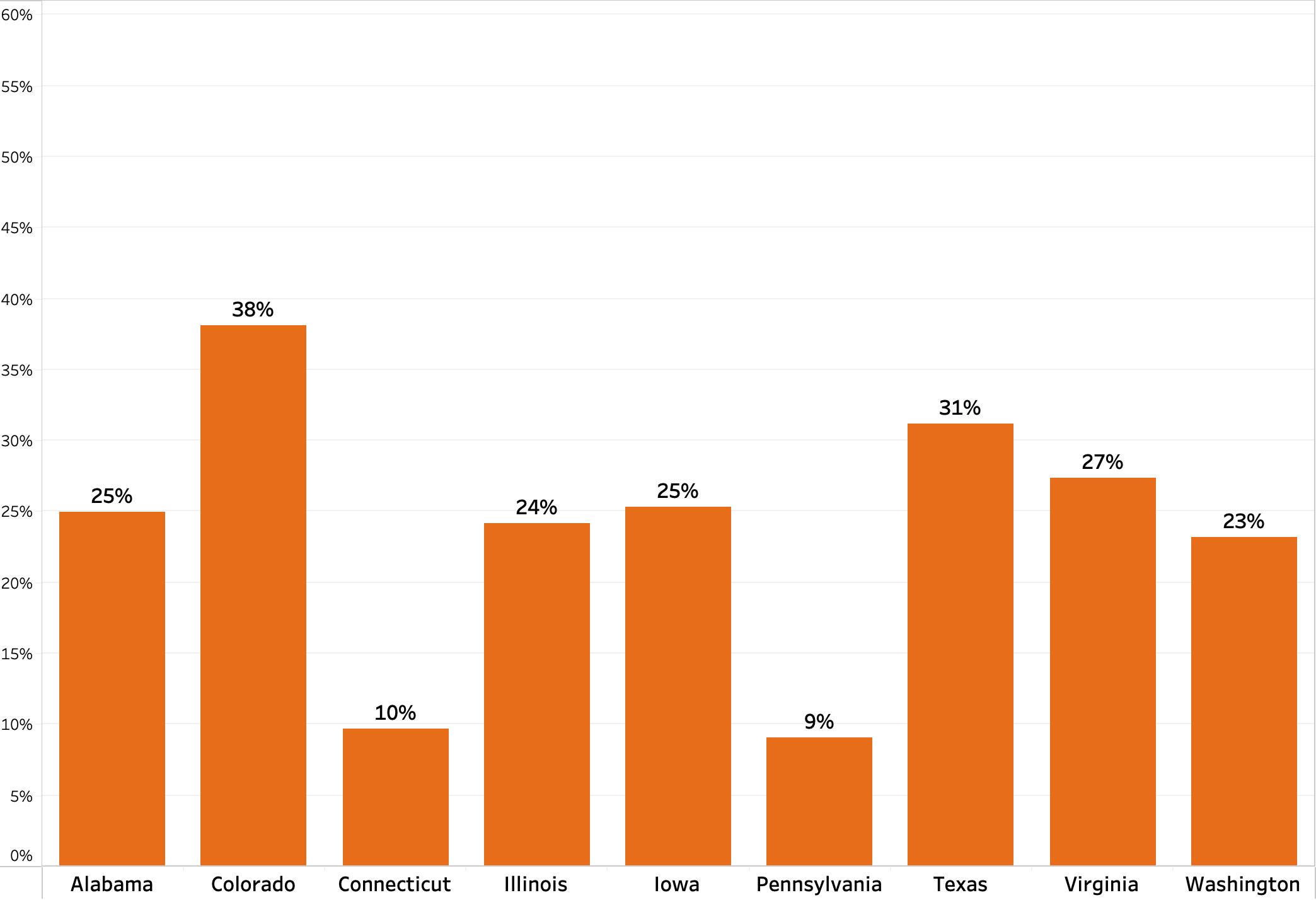

Content aggregation and curation service Newsela is by far the most recognized paid resource among surveyed teachers, with Discovery Education’s social studies “Techbook” in second place. Punching above its weight as a social studies–specific vendor is the influential DBQ Project, whose units appear in multiple places and are ranked as a highly used resource by 15 percent of surveyed teachers. Outside of Pennsylvania and Connecticut (where only 9 percent and 10 percent of surveyed teachers reported using the DBQ Project, respectively), at least 23 percent of teachers in all other sample states reported usage, with a high of 38 percent of surveyed teachers in Colorado (Fig. 24). The DBQ branding holds no relationship to the College Board’s famous AP testing instrument, but the name association undoubtedly boosts the product’s appeal.

Fig. 24: Reported DBQ Usage by State (n = 1,677)

Some products have made headway in certain states and locale types over others. Only 44 percent of rural and 49 percent of town teachers work in schools subscribed to Newsela, compared with 58 percent in cities and 52 percent in suburbs. For Discovery Education, about two of five teachers in Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia report having access versus fewer than one of five in Illinois, Iowa, and Washington. One in two surveyed Connecticut teachers have a Scholastic News/Upfront NYT subscription compared with fewer than one in 10 in Iowa and Texas. In Washington and Connecticut, between a quarter and a third of respondents (24 percent and 34 percent, respectively) reported using Brown University’s Choices curriculum, compared with 2 percent or less in Alabama, Texas, and Virginia.79

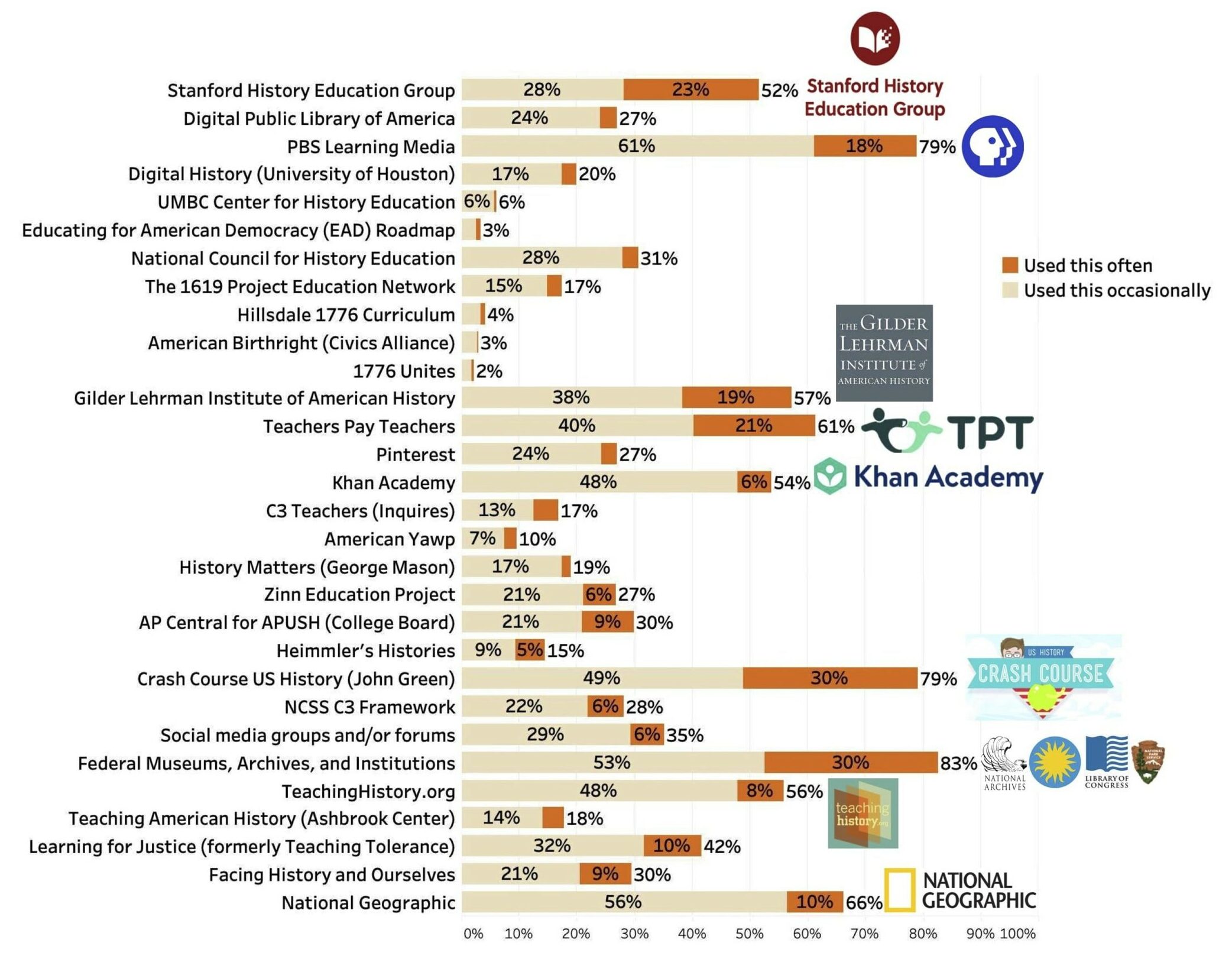

Perhaps the most significant force driving teachers and districts away from textbooks is the proliferation of free stuff (Fig. 25). Fifty-nine percent of surveyed teachers said they make use of no-cost materials from a decentralized online universe of history education providers and institutions, while another 45 percent said they use free resources from other teachers.80 In interviews, some teachers knew their favorites right away; others paused in bewilderment, realizing that they weren’t always sure where the material they use had come from. Surveyed teachers registered a high degree of trust in materials that come from federal institutions, such as the Library of Congress or the Smithsonian.

Fig. 25: Reported Teacher Usage of Selected No-Cost Resources (n range = 2,228–2,286)

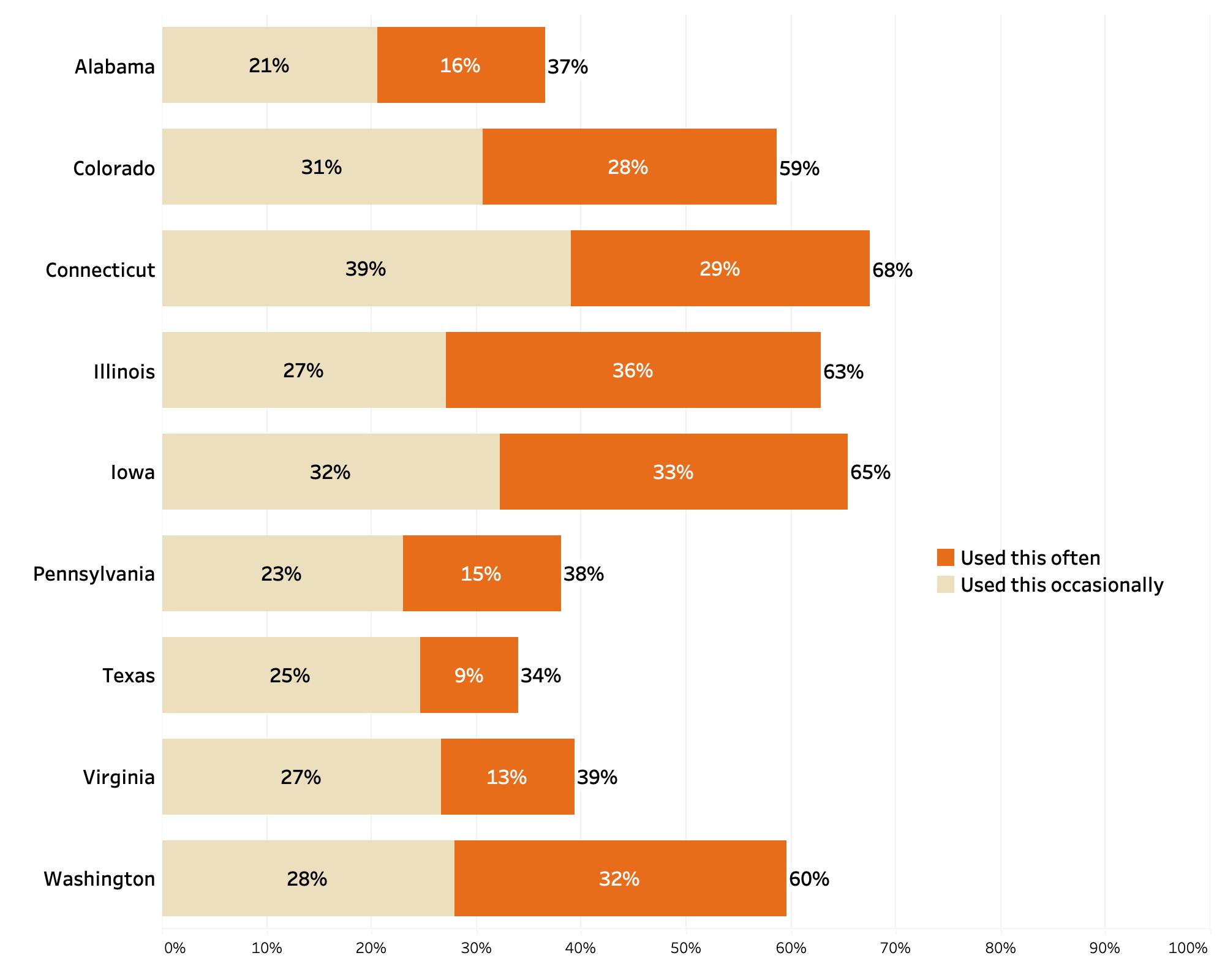

After that, the list of repeatedly used US history freebies begins with two names that most teachers outside history won’t recognize: John Green and Sam Wineburg. Green is a novelist and YouTuber, whose Crash Course US History, a 48-episode series launched in 2013, is cited as an often-used resource by more surveyed teachers than any other single digital resource listed in our survey. A smaller set of teachers find Green’s snarky quick-cut edutainment style too fast for their students to follow or too annoying to put up with.81 Wineburg is a cognitive psychologist and emeritus professor of education whose two-decade-old Stanford History Education Group (SHEG, recently reorganized as the Digital Inquiry Group, or DIG) has shown up at every level of our research. State websites link to it, district curricula recommend it, and teachers have SHEG worksheets scattered across their personal files. Among those who have heard of it, SHEG/DIG attracts repeated use and a loyal following, but its reach is not universal. High recognition and usage in Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Virginia, and Washington contrasts with a lower profile in Alabama, Pennsylvania, and Texas (Fig. 26).

Fig. 26: Reported SHEG Familiarity/Usage by State (n = 2,260)

While Crash Course and SHEG have loyal followings, many other resources fell into the category of widely recognized and occasionally used: PBS, National Geographic, Khan Academy, teachinghistory.org, and the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History all made strong showings in our survey.

Producing the most polarized data was TeachersPayTeachers (TPT), a popular online education marketplace where teachers buy and sell homemade instructional materials. TPT split teachers into two camps: 61 percent of teachers who said they use it regularly, and 36 percent who either don’t use it or purposefully avoid it. One teacher liked TPT’s ability to search for specific lesson formats, especially simulations.82 Others appreciated it as a time-saver, freeing up “time I can use helping and engaging with students instead of planning.”83 Those that purposefully avoided TPT tended to express their disapproval in strong moral terms, characterizing it as “a minefield of half-cooked ideas made by people trying to sell a hastily made pdf for $5” or “unscrupulous people taking other teacher’s work and selling it as their own.”84 Some expressed offense at “a neoliberal scheme” that contrasted with traditional norms of cost-free lesson sharing among teachers.85 As one teacher put it, “I come from mentors who retired and left all of their material to the next teacher because that is what we do.”86 Others were incredulous that teachers would pay for materials when there’s “a ton of free stuff out there and I also have a brain and skills myself.”87 Attitudes toward and usage of Teachers Pay Teachers varied widely across states. Teachers reporting frequent or occasional usage ranged from a high of 72 percent and 73 percent in Alabama and Texas, respectively, to a low of 49 percent in Connecticut. There was even sharper divergence with regard to locale type, with 29 percent of teachers in rural districts reporting regular TPT usage versus only 16 percent in suburbs. Teachers who purposefully avoided TPT were fewer but still substantial, ranging from 8 percent in Alabama to 23 percent in Connecticut, and again reflected in locale data (9 percent in rural districts and 19 percent in suburban ones). Newer teachers reported a good deal more usage of TPT (75 percent of those with fewer than five years’ experience) than veteran teachers (53 percent of those with at least 21 years’ experience). Midcareer teachers (11 to 20 years’ experience) were most skeptical of TPT, with 20 percent reporting a refusal to use it; only 9 percent of newer teachers reported avoiding it.88

Social media was also polarizing, with 35 percent of teachers reporting getting lessons from online groups or forums while 65 percent never used them (18 percent said they swore off social media purposefully). Pinterest ranked highly as an occasional source of lessons in Alabama, Texas, and Virginia but earned more skeptical responses from teachers in Colorado and Connecticut. Some teachers were simply not on social media, while others voiced concerns that recommendations in online forums were unvetted, “unreliable,” and “opinionated.”89 As one Illinois teacher explained, “I warn kids that social media is no place to get their information, so I follow the same rule.”90

Notes on Form

Part 4 of this report offers substantive appraisals of historical content in curricular materials. But the forms in which curriculum developers and social studies specialists choose to present this content matter as well. These choices express publishers’ and edtech companies’ informed judgments of the K–12 instructional materials market: a complex mix of agendas and funding streams set by education agency officials at the local, state, and federal level; the publicized advice of well-placed academic experts in curriculum and instruction; the tech and budget priorities of local administrators; and the tastes and work habits of rank-and-file teachers.

Instructional materials designed for US history classes imply an array of assumptions about how students are supposed to learn and how teachers are supposed to teach. Regarding student learning, materials range from the expository and descriptive (as in a textbook that students will read or a video that students will watch) to the inquisitive and active (directing students to conduct outside research and create a project, for instance). On teaching, materials run from plug and play (leaving questions of implementation entirely to the instructor) to highly prescriptive (with tight scripts for the teacher’s actions and utterances).

Expository Formats

Textbooks are the classic expository plug-and-play system, synthesizing various subfields of history into a chronologically arranged, image-enhanced narrative. As our survey results and interviews make clear, textbooks are rarely assigned to students as single-dose ingestions of knowledge. Teachers combine textbooks with other sources, use them for their maps and visuals, borrow their review questions and assessments, and access them via a combination of desk copies, teacher guides, and digitally interactive formats. Textbooks from leading publishers provide a spectrum of style and detail, from exceedingly dry to highly readable, and reflective of editorial judgments about the degree and type of historical contexts worth including. Publishers revise textbook editions to reflect ascendant vocabulary in curriculum and instruction, with recent editions framing units with essential questions, offering inquiry activities, and including subsections that highlight the perspectives of ethnic groups or invite students to apply historical insights to current civic issues. The visual landscape of the typical textbook can feel like a cluttered web page, with main bodies of text flanked or pierced by maps, images, insets, sidebars, section titles, question prompts, and boldfaced vocabulary. Frenzied layouts might not be conducive to focused, independent reading, but, as teachers report, this is not usually how textbooks are used.

Even when leafed through, glanced at, or used as a reference, the textbook transmits an image bank of American history, with patterns discernable across the major products from the big five publishing houses (Teachers Curriculum Institute, McGraw Hill, Savvas-Pearson, National Geographic-Cengage, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Regardless of which textbook they read, students are likely to encounter a map of the triangular trade, a reproduction of Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, a photo of Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington, and other classic visual icons. Some publishers have spliced more specialized imagery into their visual repertoire. National Geographic’s products brim with maps, cutaway diagrams of technological inventions, and elegant photographs of present-day historic sites and artifacts.91 TCI extends the life of 19th-century textbook illustrations, adorning its first-half edition with a throughline of Currier and Ives prints and paintings by illustrators like Howard Pyle and Jean Leon Gerome Ferris.92 Savvas-Pearson excels in by-the-numbers infographics, supplying stylized charts and graphs of everything from the Salem witch trials to nuclear proliferation.93

Overall, in their chapter-structured periodization, key events, famous personalities, and boldface terms, textbooks portray a mostly uncontroversial (if not always dynamic) professional consensus about the scope and sequence of content that belongs in a US history course. In this sense, textbooks are unobjectionable as a classroom resource, precisely the way that many teachers report using them. On many topics, textbooks offer more detail than the typical teacher-created or district-produced material. The social history of enslaved people, the labor history of unions in the Gilded Age, or various legal challenges to segregation before Brown v. Board of Education are all standard fare in textbooks but might not make it into a teacher PowerPoint or district pacing guide.

While textbooks languish on the shelf, narrative exposition is alive and well on YouTube. Even when districts pay for licensed digital repositories of video content, teachers default to the instantly searchable, no-cost familiarity of YouTube, where they can collect clips from the latest edutainment influencers and find many of the documentary films they used to have on a VHS tape.94 Traditional producers of documentary films (PBS, Smithsonian, History Channel) still command teacher tastes, but the YouTuber genre exemplified by Crash Course now includes an array of creators (on channels such as Hip Hughes, Heimmler’s History, Ducksters, Mr. Betts, and You Will Love History) that some teachers have grown fond of, even as others reject them as too “cute.”95 As a classroom resource, history videos function (like textbooks) in the expository mode, providing a single voice of narrative synthesis, but with a flair that textbooks rarely match.

Document-Based Inquiry96

With textbooks in retreat, the ascendant instructional format is the document-based lesson, increasingly referred to as an “inquiry task” or simply “an inquiry” in social studies circles.97 Defined broadly, the document-based inquiry lesson is a learning module centered on a central question, a set of excerpted primary documents, and a structured sequence of supporting questions, note-taking, and facilitated discussion. The lesson typically concludes with some culminating task in which students, either individually or in a group, deploy their readings of the primary documents as evidence in support of a position, a response to the central question posed at the outset. These central questions are designed to speak to big debates—unresolved issues that can motivate class discussion and set terms for a final assessment. As a catchall for these approaches, “inquiry” is everywhere, dovetailing with curriculum experts’ insistence on “essential questions” and “enduring understandings.”98 Professional networks put inquiry at the center of their descriptions of best practices, and social studies standards in multiple states now echo the C3 Framework—produced by a coalition of professional organizations including the AHA and NCSS—in centering inquiry as both process and goal.99

The basic intellectual and pedagogical moves of the document-based lesson date to the 19th century, when the first generation of professional historians called on schoolteachers to depart from the blunt moralism of many textbooks. Instead, historians endorsed more direct encounters with primary sources and even “topical study” by way of individual research projects with preselected source bases.100 As teacher educator and historian Mary Sheldon Barnes advised as early as 1891, “Give the student a little collection of historic data, and extracts from contemporary sources, together with a few questions within his power to answer from these materials. Then let him go by himself.”101 Skeptical of a purely source-driven approach, the AHA’s Committee of Seven stressed in their 1899 report that textbooks were indispensable, advising “limited contact with a limited body” of primary sources—mainly as a way to vitalize the subject and not as an effort to reenact “investigation.”102

If investigation remained a dirty word to some historians, by 1920 it had become a mantra for an interdisciplinary coalition of New History proponents, social studies advocates, and progressive curriculum developers.103 Seeing history’s proper role in general education as “understanding the most vital problems of the present” and informed by scientific curriculum design, social studies specialists designed courses like Community Civics and Problems of Democracy with “problems” or “issues” at their core.104 By midcentury, government and foundation-funded “New Social Studies” projects that promised to sharpen history’s intellectual profile by foregrounding inquiry as a process. Drawing from the latest in cognitive psychology, curriculum specialists produced templates for “inductive” or “discovery” approaches to history education, even as many proved too ambitious or expensive to enact at scale.105 Among the era’s lasting legacies was the AP US History exam’s document-based question (DBQ), first introduced in 1974.106

Today’s document-based inquiry powerhouses, SHEG/DIG and the DBQ Project, have intellectual roots in the New Social Studies era, but they owe their success to the particulars of the early 21st century. SHEG, founded in the internet age and reared in an era of ambitious new federal educational accountability initiatives, was the curricular expression of Wineburg’s thesis about character and value of historical thinking.107 As Abby Reisman, an education scholar and one of SHEG’s early curricular designers, saw it, prior attempts to install history-as-inquiry in the classroom were unrealistically grandiose. Scrutinizing the rhythms of teachers’ daily grind, SHEG was forthrightly pragmatic, offering a finite set of “classroom-ready materials” to plug into “a predictable and repeatable sequence” that teachers could recognize.108 In the language of education scholarship, SHEG’s developers leaned confidently into the “grammar of schooling,” rather than imagining that they could disrupt it.109

SHEG’s extensive (and free) collection of lessons anchored historical thinking in the cognitive encounter with primary documents. Its widely used chart of mental moves—sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and close reading—help teachers and students ask the right questions about primary sources. SHEG’s “HATs” (Historical Assessments of Thinking) push the skills-training idea further, suggesting that teachers track a single aspect of students’ historical thinking across successive formative assessments. As sophisticated as SHEG became at disaggregating the cognitive components of document reading, its designers remained largely aloof from (and occasionally antagonistic to) narrative synthesis.110 SHEG’s document-based learning approach proved a comfortable fit with the emphasis on nonfiction literacy that dominated the accountability era.111 In the Common Core era, SHEG’s advice about how to “read like a historian” could also be pitched as preparation for the next standardized test.

The DBQ Project’s approach shares much with SHEG but pays extra attention to evidence-based argumentative writing, another focus of Common Core. The DBQ Project’s method combines a focused historical question or “hook,” with a background information essay, a primary source collection with guiding questions, an analysis stage with folksy euphemisms (e.g., “Bucketing,” “Chickenfooting,” and “Thrashing-out”), and a writing product, which often takes the form of a thesis-driven essay or occasionally a creative exercise.112 In some modules, students (and teachers) weigh historical and historiographical arguments. Like SHEG, the DBQ Project’s lessons are modular, designed to be inserted into an existing curriculum, but they are generally less likely to fit within a single class period.

DBQ and SHEG are no longer the only inquiry products available. Curriculum vendors and nonprofits pitch various branded versions: “DBQuests” from iCivics, “Inquiry Journeys” from InquireEd, “Investigations” from Read.Inquire.Write. Teachers can also find bundles of material with document-based or inquiry-focused tags on TeachersPayTeachers. Over the past decade, C3 Teachers, a startup launched by three of the lead authors of the C3 Framework, has been particularly successful at promoting its “inquiry design model” (IDM) blueprint across a network of state-based hubs. Some state agencies have made document-based inquiry a centerpiece of their efforts to encourage alignment to the C3 Framework.113 In Virginia, recent changes to the state’s assessment rules now allow local districts to use IDM-branded inquiries instead of traditional multiple choice tests for “verified credits.”114 In some districts, document-based inquiry has become a part of teacher evaluation rituals. A large Illinois district requires its social studies teachers to administer a beginning-of-year and end-of-year performance task that sits outside of chronological content coverage and assesses students’ skills at document-reading and claim-making. Student growth between each assessment accounts for a portion of the teacher’s evaluation rating.115

No Such Thing as a Bad Question?116

In many instances, the prevalence of essential questions and document-based inquiry seems likely to deliver on its promise of promoting historical thinking.117 Asking about historical circumstances—how the shift to the factory system affected American workers, or what motivated US policy during the Cold War—encourages an exploration of multiple scales and genres of context.118 Asking about historical outcomes—whether the American Revolution was avoidable, why the Montgomery Bus Boycott succeeded, or why the Equal Rights Amendment was defeated—requires students to deal with complex causation in chronological sequence and to think through the structural constraints on historical agency.119 Good questions like these appear across a variety of units and lessons.

Not all questions are created equal, however. Forced choices between moral absolutes, abstract queries of moral or civic concern, and overly fanciful counterfactuals abound. Stark and uncomplicated question constructions can too easily speed the inquiry process straight to argument, reducing history to a series of positions that one must take and defend.

Too many lessons ask students to stake a position on a moral binary, rendering judgment on a past policy or person from the perspective of a national (and present-tense) “we.” Questions that ask whether slavery was bad or if American imperialism sacrificed freedom for power seem prebaked to generate only one conclusion, a litmus test to see if students have absorbed the right set of feelings about past events or an invitation to assume that they would have been “on the right side” had they lived at the time.120 Inquiries that ask students to render a verdict on whether the Boston Tea Party or the US War with Mexico were “justified” can spur consideration of causes and consequences, but they privilege lawyerly thinking over historical understanding.121 Even more blunt are the recurring assignments that require historical figures to be rated as heroes or villains. (Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Jackson are frequent defendants in such trials of character).122

The good intentions behind such prompts should not be dismissed. Engaging students with history often begins with indelicate provocation—a hook to awaken their own sense of what feels foreign and familiar about the past. Teachers can indeed encourage students to sit with a sense of moral disgust (slavery was wrong!), policy judgment (the US War with Mexico was not justified!), or psychic connection (Carnegie is my hero!). But such feelings and judgments are reminders that people in the past made choices within particular and peculiar contexts. And they should ideally serve as a preface for bigger, better questions that plumb the past and unsettle the naturalness of our present. When, why, and for whom did slavery become a moral problem? To whom were arguments justifying (and opposing) the US War with Mexico convincing, and why? How, when, and why did Americans develop their taste for rags to riches stories? How did industrial capitalists like Andrew Carnegie use their wealth to shape their legacy?

In some cases, a compelling question will edit out the historical characters, contexts, and events in order to build headier metaphysical stakes. Asking “what it means to be equal” or “how democracy should work” or “whether compromise is fair” are certainly compelling questions.123 Our skepticism does not amount to dissent from the longstanding article of faith among historians that historical inquiry sharpens students’ capacities for judgment, capacities that they will ultimately turn toward moral and civic issues. In class, however, the overheated stakes of backward-design-style “compelling questions” set up a mismatch between philosophical dilemmas and the tiny set of historical excerpts under study. History should help foster the skills and perspective necessary to historicize ourselves and our present, but it cannot be expected to resolve such fundamental questions or to speak its counsel in aphorism, analogy, or moral lesson. Moreover, historical thinking should help students to learn that judgment generally must be preceded by informed understanding.

A clearly positive effect of document-based inquiry has been teachers’ unanimous embrace of using primary sources with students. But the rush to turn primary sources into digestible and deployable units of evidence has produced collateral damage in the form of decontextualization. In the typical document-based lesson, sources come disembodied from their original contexts and in heavily excerpted formats. Far from staging a textured and stirring encounter with the past, many document-based lessons are designed toward more instrumental outcomes (extract the main idea; use this detail to support a claim). Responding to the reasonable concern that students may be unprepared to decode the challenging language found in many primary documents, lessons tend toward passages that have been plucked, trimmed, and even altered from the original. Unavoidable choices about how to edit, curate, and transcribe are one thing; the washing out of rhetoric and the wiping out of context is another.

Several online resources and digital textbooks now boast of customizable reading levels, but content aggregator Newsela is an especially popular paid resource with this feature. With content scraped from news and history websites (many of which are the popular free resources that teachers use on their own) and arranged in traditional chronological units or searchable by topic, Newsela can generate customized document packets with introductory remarks and scaffolded questions–with a note that their “suggestions have been generated by an AI model.”124 Teachers appreciate Newsela for its on-demand plug-and-play modularity and the five different reading levels that could be applied to any text, including primary sources. Some of Newsela’s contextual information is so broad that it may offer students little guidance; “The Civil War had a profound impact on American society, economics, and politics” borders on the banal.

A more serious problem arises when a provider changes the actual words of a primary source in accordance with reading levels, negating the aesthetic and distinctly human encounter with the past that a historical document is meant to provide (Table 3).

Table 3: The Gettysburg Address Adjusted for Reading Level

| Original | Adjusted to 880 Lexile125 |

|---|---|

| Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. | Eighty-seven years ago, our Founding Fathers created a new nation on this land. The country was born out of freedoms that we fought for. It was dedicated to the idea that all men are created equal. Now, this nation is engaged in a great civil war. The fighting between the North and the South is testing whether this nation, or any nation that shares our values, can last. Today, we stand on one of the great battlefields of this civil war. We have come to dedicate a part of this field, as a final resting place for the soldiers who gave their lives here. They died so this nation might continue to live. It is right for us to honor them. However, in a way, we cannot call these grounds holy or divine. Brave men fought here, and some lived and some died. Those who struggled here have already made this land holy. These soldiers did much more than we are able to do today. The world will not write or talk much about what we say here. The world will not remember what was said here for long. However, the world can never forget what the soldiers did here. It is us, the living, who are called here. We are called to the unfinished work which our soldiers have begun so nobly. For these honored dead we must increase our devotion to the cause that they died for. We must make sure that these men shall not have died in vain, so that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom. We must decide that the government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not disappear from the earth. |

Note: MetaMetrics, the developer of Lexiles, considers the 880 Lexile within the range of “proficient” (on grade level) for students from 4th through 7th grades.

Other Formats

Other curricular products bill themselves under the inquiry banner, but their materials are better understood as historical simulations. Whether in the form of roleplay, case studies, or RAFT (Role, Audience, Format, Task) writing exercises, these lessons place students in the role of historical figures. Role-playing lessons are typically designed either to help students imagine the inner lives of historical actors or to reenact the stakes and choices surrounding a critical decision. A range of typical classroom activities gesture toward roleplay and reenactment at small scales, from “write a journal as” assignments to encounters with local living history sites and any query that asks “what would you have done?” More elaborate curricular versions of the concept create games or cases out of a specific historical scenario. Formats and quirks initiated by The Oregon Trail computer game persist in some of these simulations.126 More distinguished role-playing products like Brown University’s Choices Curriculum and Harvard Business School’s Case Method are marked by complex multistep, multicharacter formats. In Choices units, the “options” moment—when a student is tasked with making a decision as a historical actor—is preceded by substantial historical and historiographical context. With lengthy and challenging units pitched at college preparatory markets, Choices advertises its connection to the Brown University history department, its access to experts, and “up-to-date historiography.”127 Because of the complex sequence of roles and tasks involved, these curricula tend to be highly prescriptive and resistant to the modular plug-and-play approach. Both Choices and Harvard Case require a subscription, and Harvard Case requires that teachers attend a training institute before accessing materials.128

While some teachers noted a “big move toward buying packaged curriculum,” districts are increasingly looking for more customized products that suit their stated priorities. When curriculum developers are contracted by districts to develop instructional materials, a tendency toward heavily scripted, all-inclusive packages prevails. A large Illinois district’s contract with a major textbook publisher to collaboratively build a fully digital product has attracted controversy for its high price tag and low buy-in from teachers.129 A set of suburban Washington districts contracted with a smaller developer to create project-based units centered on essential questions, progressive values, and multimedia student projects.130 A classical charter school network in Colorado stays closely tied to a common US history curriculum rooted in primary documents, annotation, and a tight script of questions.131 Radically different from each other in form and philosophy, these examples share a common goal of creating a centralized choreography for the individual moves and methods deployed in the act of teaching, pushing the page count of some of these documents into the thousands.

Every sample of local instructional material we reviewed revealed new idiosyncrasies. Official paperwork issued by a district often bore little resemblance to what a course team or department chair handed in to their principal, what an individual teacher used to plan their units, or what was handed out to students in class. If the typical district document was a gridded matrix crowded with number-coded standards and skills-aligned learning objectives, the typical teacher document was an endless cascade of folders and hyperlinks—a multimedia mashup of experiences accumulated and amended over the years. A single folder might contain viewing guides and YouTube links to clips of a Ken Burns documentary, photoscanned handouts from an older textbook, a full-length mp4 of Edward Zwick’s Glory, a teacher-authored DBQ assessment featuring Thomas Nast cartoons from Harper’s Weekly, and a modular thinking assessment from a curriculum developer like SHEG.

This decentralized miscellanea may be uncomfortable to many education agency administrators. But based on our interviews with hundreds of teachers and administrators, we are skeptical of the value of turning teacher guides or unit plans into extravagantly detailed scripts. Administrators are right to be concerned about the quality and rigor of in-use materials, but overbearing standardization runs counter to the longstanding and widely embraced goal of social studies: to foster new generations of independent-thinking, self-governing citizens. If teachers are too regimented to enact these habits as professionals, they will have little hope of modeling them for their students.

Vibes and Pressures

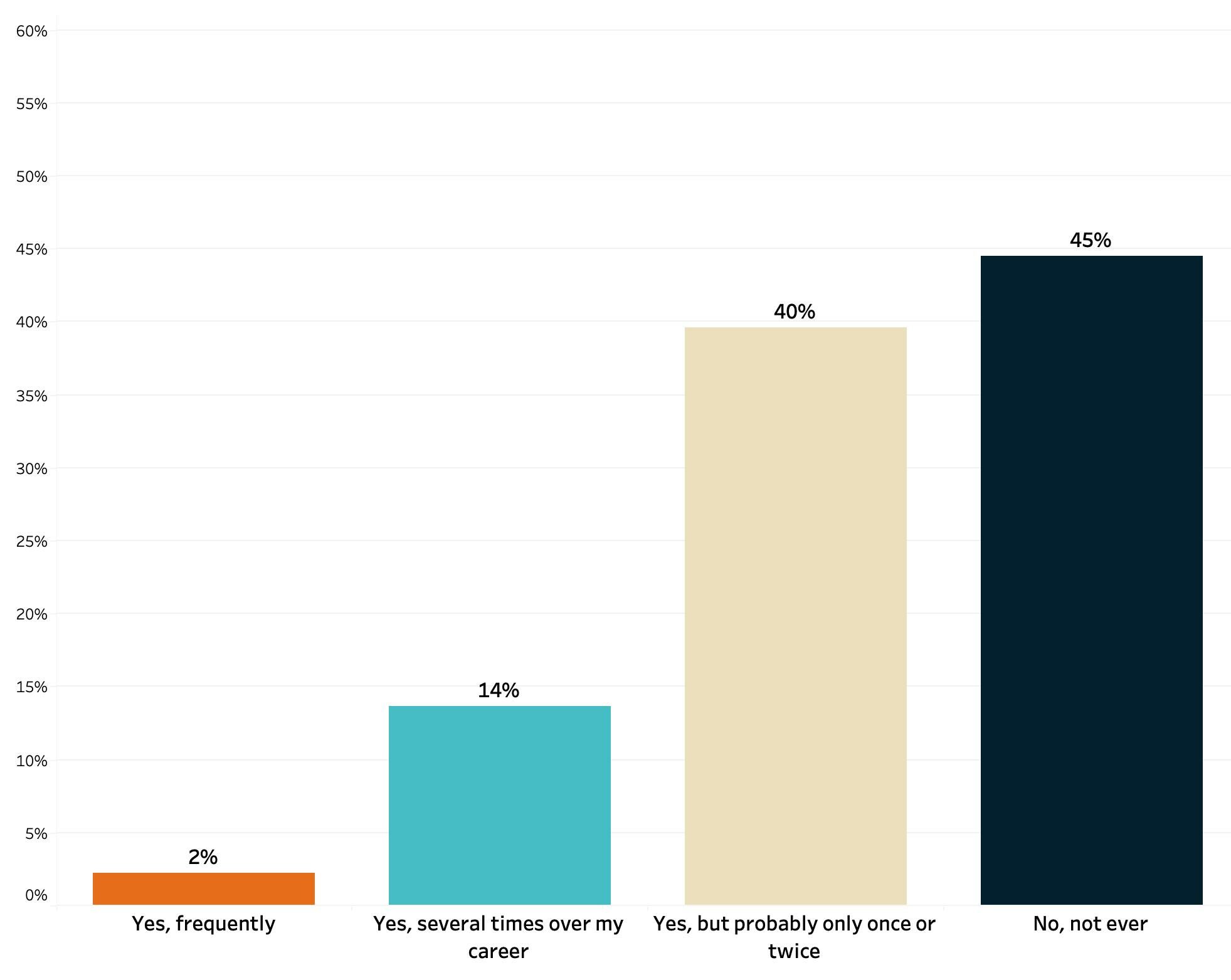

A fuller view of everyday teaching contradicts media accounts that portray the typical American school district as engulfed in a politically charged war for the core values and identity of our nation.132 With the exception of those working in certain hotspots, most teachers report that they do not face politicized pressure at their job with any consistency. Only 2 percent of surveyed teachers said that they regularly face criticism related to the way they teach topics in US history, while 40 percent report having encountered an objection only once or twice in their career and 45 percent report having never encountered an objection to anything they’ve taught (Fig. 27).133 Punitive legislation, public tip lines, book bans, and angry activists: these are real threats with serious implications for teachers across the country, but thus far much of their direct influence has remained localized in certain states and districts. Many of the educators we interviewed expressed alarm about reports of extreme conditions in Florida and other hot spots.134 Comparatively few have extensive personal experience with direct challenges to educational decisions. Far from fending off throngs of energized and oppositional parents, many social studies teachers struggle to get parents, students, and even administrators to care about history at all. When teachers do encounter politicized pushback, many express confidence in defending the integrity of good history and commit themselves to praiseworthy principles of neutrality and nonpartisanship. On the importance of neutrality, teachers said:

- “[I am] going to teach the good, the bad and the ugly. I’m going to tell it like it is and how it happened.” (Texas)135

- “I will cover things that are politically difficult and controversial. You can’t teach it well and do that. But . . . I’m very careful to be non-partisan.” (Texas)136

- “I would tell a younger teacher—you have to stay neutral when you teach and then the parents don’t have a leg to stand on. If you stay neutral and you’re not clearly on one side or the other of an issue then you can push back.” (Virginia)137

- “I try to be as neutral as I can. I also don’t want students knowing my views.” (Illinois)138

Fig. 27: Have You Faced Objections or Criticisms to the Way You Teach US History? (n = 2,258)

This good news notwithstanding, politics and ideology are indeed part of the mix of vibes and pressures that shape the work of history teaching. Teachers have idiosyncratic passions that inflect the plotlines of the stories they tell. Curriculum publishers aiming to sell to particular social enclaves sometimes design products matched to the ideologies of niche markets. Administrators face pressure to reflect the political currents that hold sway in their communities or within their professional networks. Parents will object when something bothers them. Activists will seize on opportunities to organize discontent. And teenagers will resist a great deal of what any of these adults try to pitch to them.

Polarization and Pandemic

The AHA began interviewing educators in 2022 as some districts were completing their first full year of normal schooling following the COVID-19 pandemic closures and remote instruction policies of 2020 and 2021. In early interviews, teachers shared fresh memories of pandemic-era challenges and ongoing frustrations with postpandemic adjustments. For some, the cascade of challenges introduced during the COVID era were still present: the wholesale move to digital platforms had rendered their older materials and methods unusable; an “everyone passes!” policy on assessment and promotion had fostered “lazy learners;” parents with an activist impulse had become more politicized, organized, and sometimes confrontational; and student misbehavior was rampant.139 By the time we completed our final interviews in 2024, mentions of COVID-associated challenges had faded, even as a general sense of students’ diminished capacities remained.140

The sigh of relief with which many teachers greeted the return of normal schooling expressed, in some cases, a wish that certain political dynamics would also abate. A few teachers noted that political polarization predated the pandemic, recalling the 2016 election as a moment when they noticed students expressing themselves in more overtly politicized terms than previously. Recalling the heightened debates over immigration policy, one Illinois teacher described her classroom: “Some kids were like ‘send ‘em back’ and the other students say ‘hello, we’re right here.’”141 Several teachers credited students’ enhanced political awareness to the reach of technology and social media, making students “so much more connected,” and thus more fluent with the various sides and slogans that constitute political opinion.142

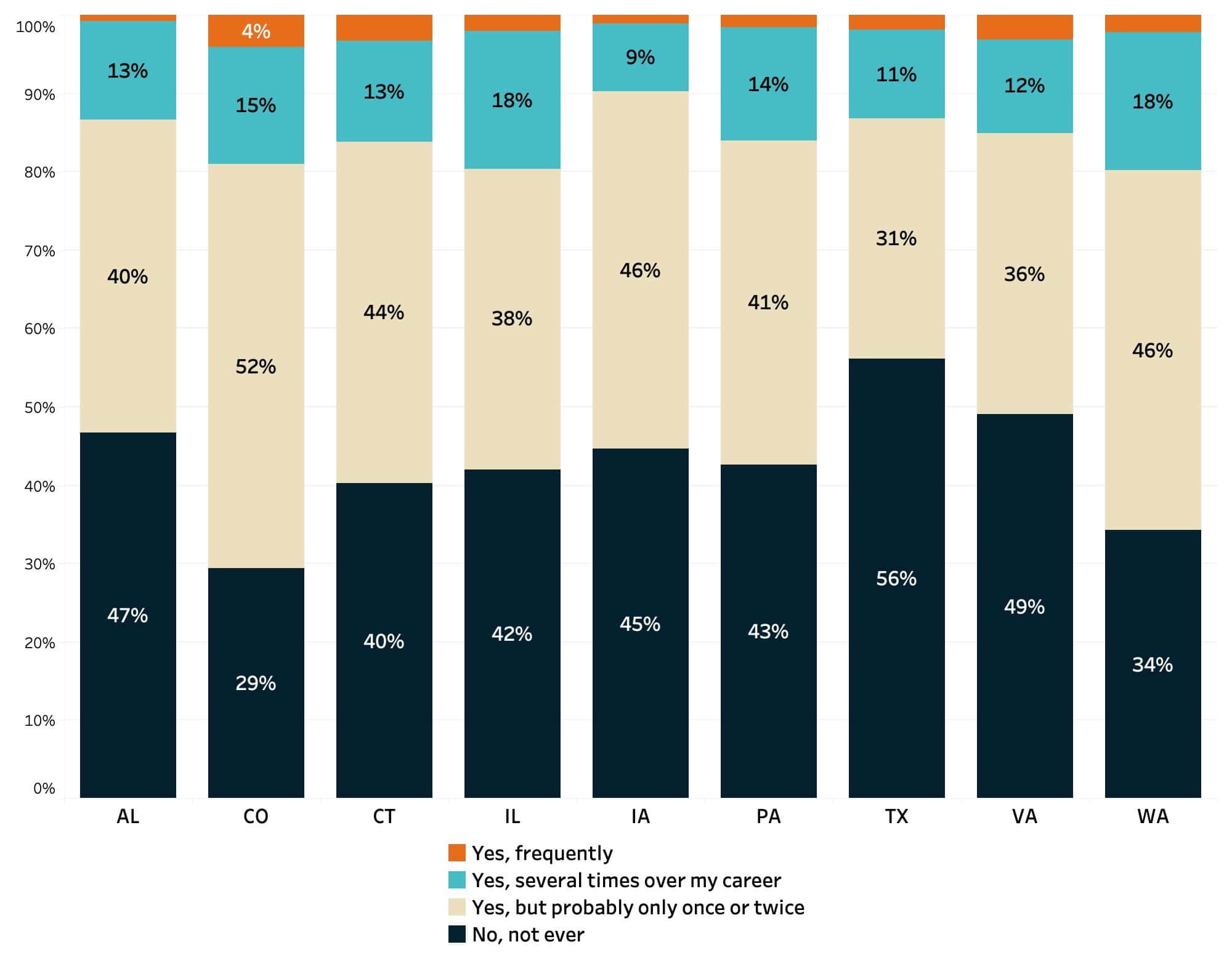

Teachers’ experience with direct criticism varies. Teachers in Texas, Virginia, and Alabama were most likely to report that they had never had any pushback during their careers (56 percent, 49 percent, and 47 percent of those surveyed, respectively) (Fig. 28). While low overall, rates of reported experience with direct criticism among surveyed teachers revealed some correlation with the social profile of their communities. Teachers working in wealthier districts (as measured by the rates of free-and-reduced-lunch-qualified students) were the most likely (17 percent) to report having experienced objections “several times” over the course of their career. Meanwhile, teachers working in low-income districts were far more likely to report (51 percent) that they had never experienced any criticism. Suburban teachers were likeliest to report experiencing challenges at some point in their careers, while other locales showed little variation. In interviews, teachers supplied anecdotal analysis of these patterns. As one Colorado teacher put it, the “toughest population are the very, very affluent suburbs” where parents have lots of free time on their hands.143 An Illinois teacher noted that when people asked him why his district seemed so calm, he replied, “My wife thinks it’s because we’re such a blue-collar area, that people are just busy.”144 A Washington teacher agreed: “Parents working two or three jobs [have] no time to get into my face.”145 For some teachers, the passing of the pandemic era appears to be dispersing political pressures. As one Virginia teacher guessed, “Maybe parents are more busy or not working from home, but they aren’t paying too much attention anymore.”146

Fig. 28: Teachers’ Reported Experience with Objections and Criticism, by State and Locale (n = 2,258)

Materials Teachers Avoid

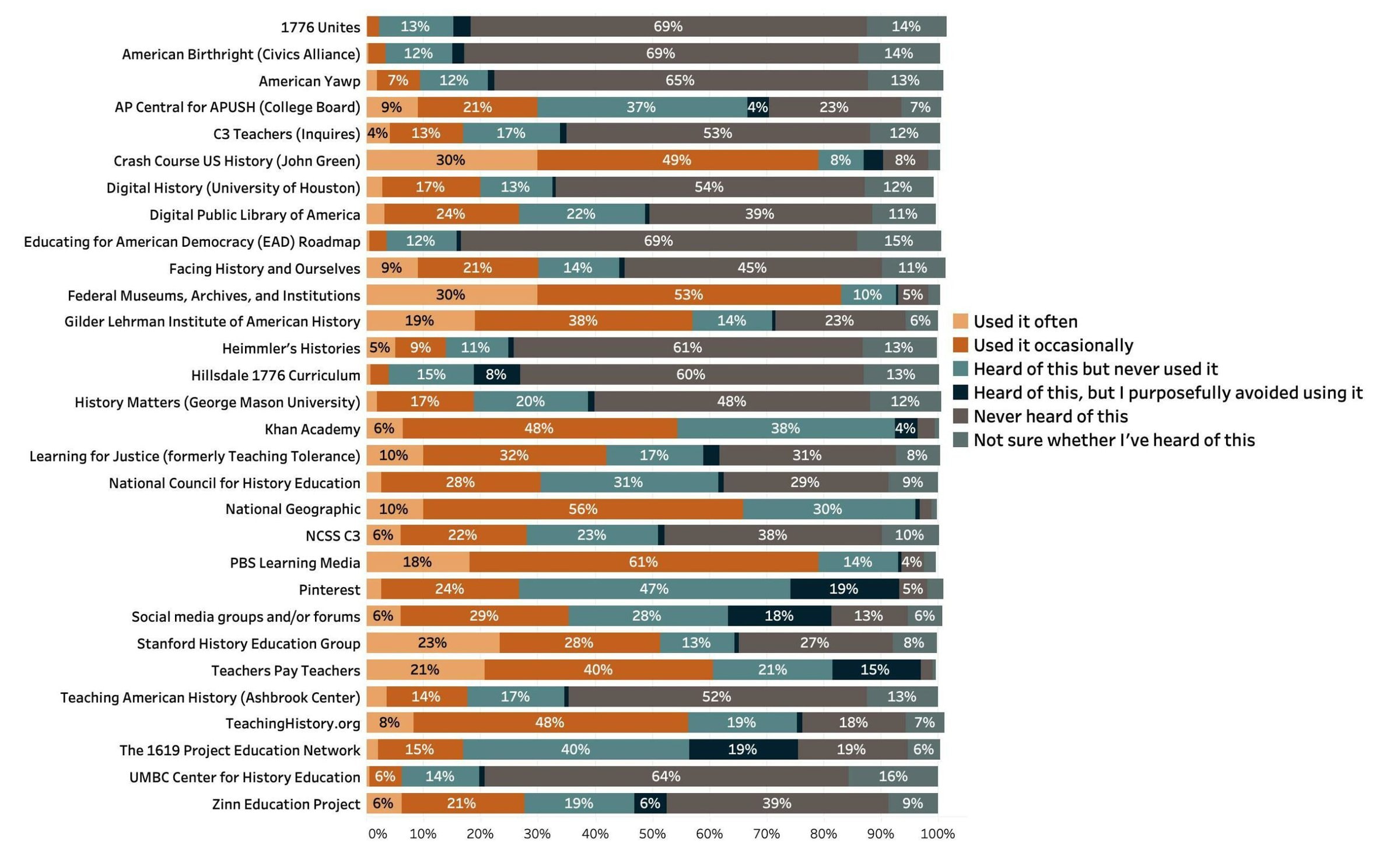

Unlike Pinterest or Teachers Pay Teachers, which detractors critiqued as shoddy or mercenary, a few resources earned suspicion from surveyed teachers because of what they or others judged as an ideological bias. The short list of resources that teachers reported avoiding are included in Fig. 29.

Fig. 29: Reported Usage and Avoidance of Social Studies Resources (n range = 2,233–2,286)

Among the sites that provide a centrally coordinated collection of materials, two registered noticeably higher rates of purposeful avoidance. The 1619 Project Education Network, a hub of teacher-produced materials hosted by the Pulitzer Center and spun off from The New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, earned the top spot on the list of resources that teachers reported purposefully avoiding.147 There were sharp variations along lines of geography and teacher tenure with regard to the 1619 Project, with far more avoiders than users in some more politically conservative states, while other traditionally liberal states tallied more occasional users than those keeping their distance.148 The longer a teacher’s career, the cooler their reaction to the 1619 Project was likely to be, with veteran teachers (22 percent) slightly more likely to report avoidance and newer teachers (13 percent) showing the least avoidance. Though significantly less recognized, the Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum, a K–12 civics and history curriculum produced by Hillsdale College, a Christian liberal arts college in Michigan, also registered strong negative reactions.149

When asked to elaborate on why they avoided these resources, teacher responses converged on the issue of political bias. Among the teachers who elaborated on their avoidance of the 1619 Project, responses fell into three categories. Most common was a perception that the project contained politically motivated inaccuracies—an “agenda-driven” “slant” that was “ideological and not factual.”150 A few within this group noted the critiques that the 1619 Project had earned from professional historians; these teachers described the work as “academically irresponsible,” “race reductionist,” or inattentive to historical agency and economic history.151 Another substantial set of teachers assigned their choice to avoid the 1619 Project to “the temperature of the current community,” either describing their sense that it was a “trigger” for “controversy” that they did not want, or that state law or local district authorities expressly prohibited them “from using 1619 project materials.”152 A third, smaller set of teachers used stronger language to signal their sympathies with the efforts of conservative activists. In these responses, teachers described the 1619 Project as “fake,” “racist,” “divisive,” or “anti-white.” As a Texas teacher put it, “I do not indoctrinate my students with liberal ideology.”153

As for the 1776 Curriculum, reactions were far fewer (60 percent of surveyed teachers had never heard of it), but similar suspicions about partisan bias underwrote teacher motives of avoidance.154 A number of teachers associated Hillsdale with an “intentionally political” “Christian conservative” bias that was “not academically sound.”155 Others used more strident terms, condemning Hillsdale as “fascists,” or “right-wing nutjobs.”156 A few teachers took the opportunity to explain that they saw pedagogical value to polarized curricular products like these. As one Pennsylvania teacher remarked, “My students have great fun reading the Intro [to] the 1619 project alongside the 1776 project manifesto.”157 Another teacher in Virginia agreed, having done a similar activity with college-level students, but that “this is not something that I would do in my regular level history courses.”158 Referring to both the 1619 Project and 1776 Curriculum as “propaganda,” one Iowa teacher characterized them as “either left ideology that just isn’t true [or] right wing, ‘everything about America is awesome’ bull.”159 In general, the data support a conclusion that anyone with access to local classrooms might have predicted: curricular products that come precoated with politicized associations can expect a cool reception from teachers. There are other curricular providers whose ideological leanings are present but less extreme, and they enjoy far warmer reactions as a result. Facing History and Ourselves leans into progressive multiculturalism but registers no strong signals of avoidance. The Ashbrook Center’s Teaching American History emphasizes a traditionalist view of civic virtue, but teachers showed no evidence that they associated its resources with a political position.160

As a result, very few of the prescribed or in-use materials that we examined could be described as containing a strong ideological skew. Exceptions worthy of mention tended to occur in settings where administrators and active community members shared a set of political outlooks. As one Washington teacher observed of his deep-blue district, it was easy to teach a “very progressive curriculum” with “little blowback about it.”161 Similarly, teachers in a conservative Colorado charter network described their sense that parents were “on board” for their school to have “a clear perspective” and “speak to [the] moral formation and character” of students. As one teacher put it, “We say who we are.”162

Seen from one angle, these convergences are precisely what local educational governance is meant to deliver: school communities where adult stakeholders agree on a coherent curricular vision. With class, culture, and politics mapped onto to school district boundaries, however, curricular vision can slide into an ideological mission. When learning goals become more affective than academic, historical content suffers.

Pressures in Blue and Red