Contents

Courses of Study

State Standards and State Agencies

State Assessment

State Legislation

Struggling to describe the US education state, scholars and policy advocates have mixed their metaphors to invoke complexity, fragmentation and even frustration—a “crazy quilt” of “marble cake federalism,” “bureaucratization without centralization,” a “game of telephone,” “too many chefs in the school governance kitchen,” “set up to thwart policy success.”1 Others find energy in the mix, noting the enduring “dynamism” of James Madison’s compound republic.2 The clutter of educational governance notwithstanding, a national view of US history education reveals meaningful patterns and notable divergences. This section maps these institutional contexts, which shape the local and teacher decisions cataloged in Parts 3 and 4.

Courses of Study

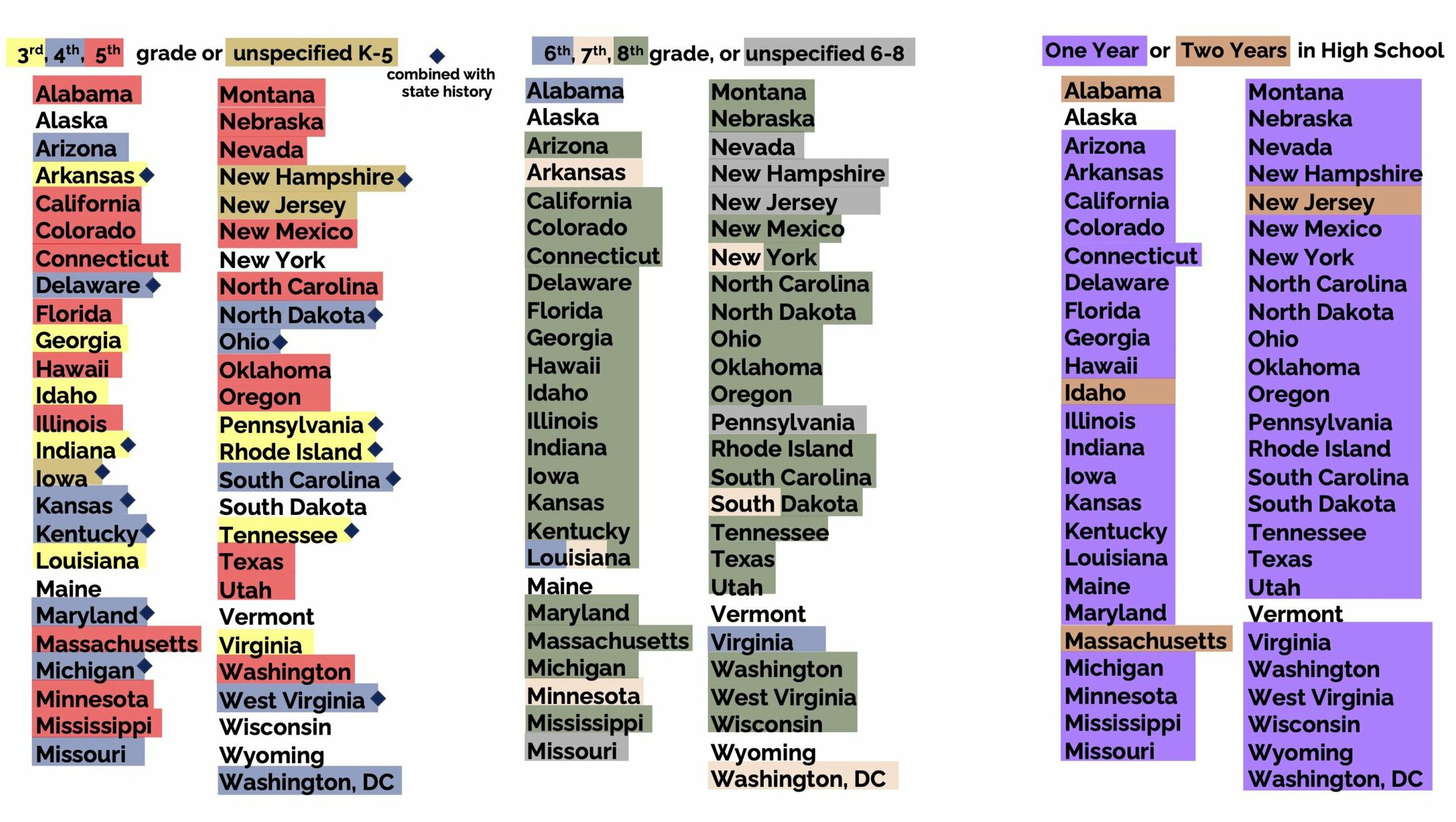

In the courses of study across 50 states and the District of Columbia, 43 introduce US history content for the first time somewhere within grades 3 through 5, with 5th grade the most common. Fifteen of those states combine students’ first dose of US history with state history. Thirty-nine states require or recommend more US history in middle school, most often in grade 8, or with far less frequency in a two- or three-part sequence. All states that provide guidance require at least one US history course in high school, typically in one year, with a few in a two-year sequence (Fig. 7). A handful of states offer no state-level guidance or description of courses of study.

Fig. 7: Sequence of Required and Recommended Courses in US History

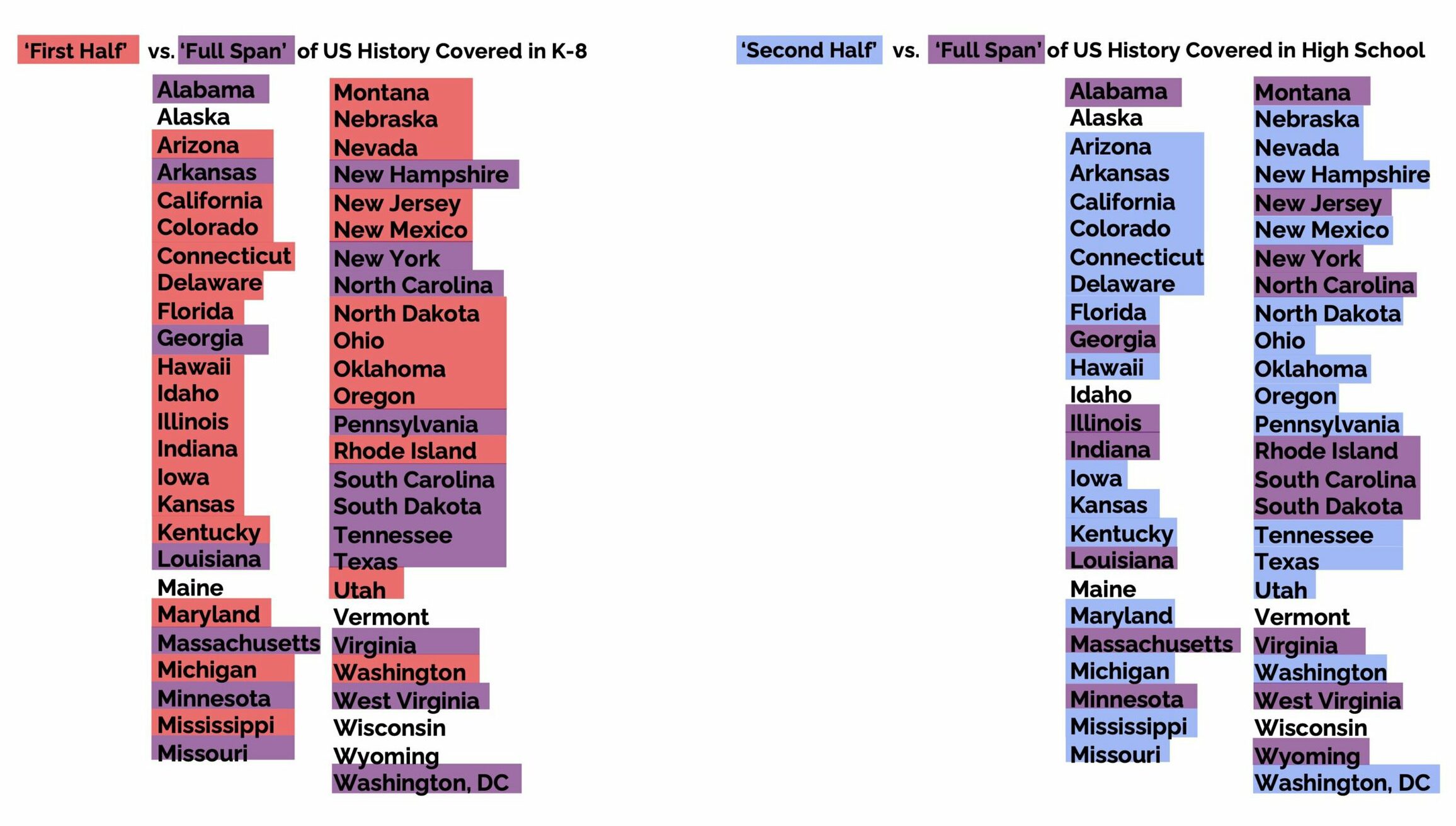

Despite consistencies regarding when students take US history, there is important variation in the scope of the content covered at these different grade levels. Most K–8 US history courses cover content from the so-called “first-half” of US history, starting somewhere between the original inhabitants of the Americas and the US Constitution and continuing to the end of Reconstruction.3 Only 18 states appear to cover the full span before the beginning of high school. In 23 states, the required high school US history course covers content only from the “second half” of the timeline, picking up wherever students left off in middle school (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Scope of US History Content Coverage

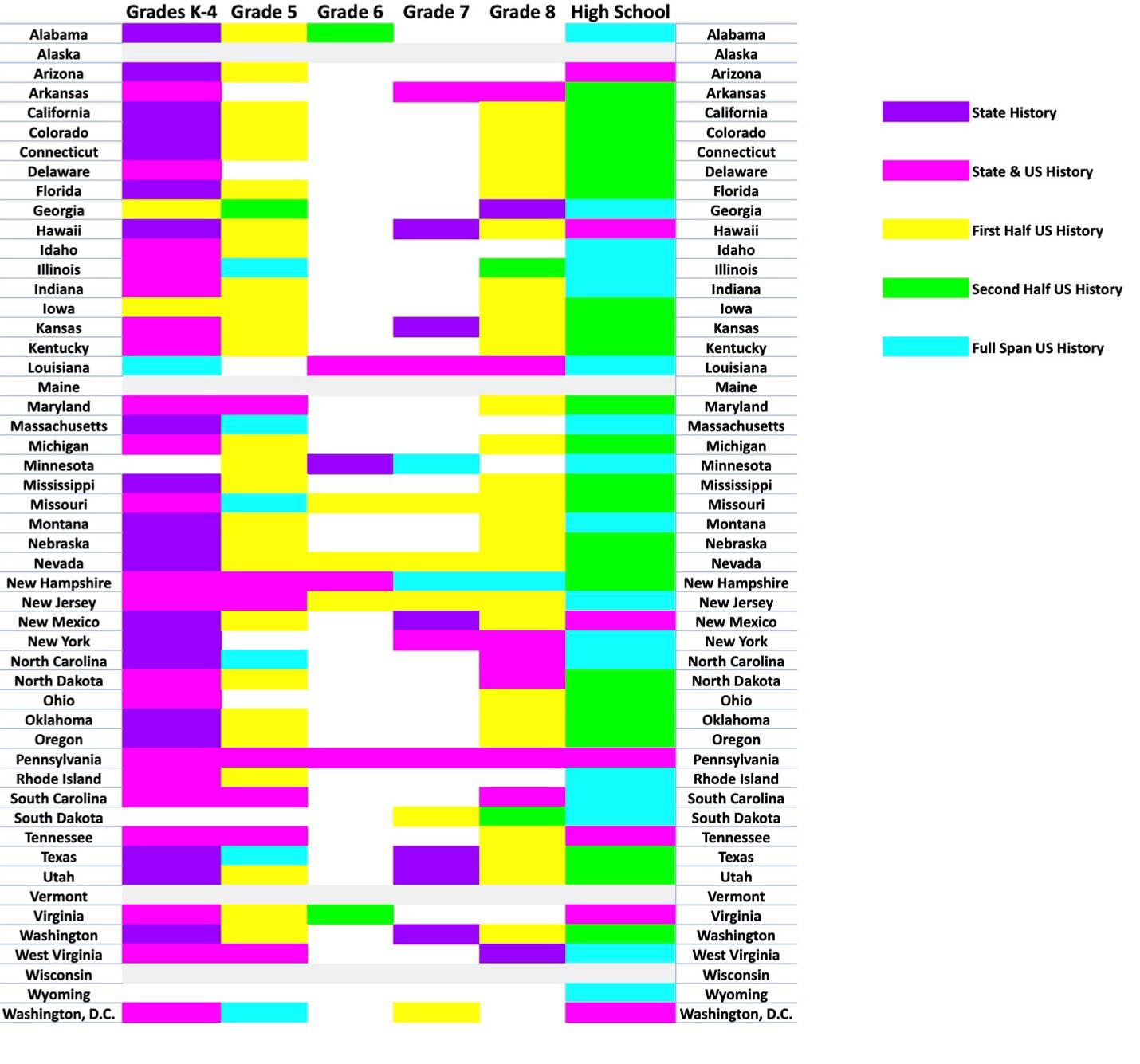

Color coding these course sequences across all 50 states and DC and adding state history requirements yields a clear clumping of coursework and content across common grade bands (Fig. 9). This pattern of state history in K–4 and US history in 5th grade, 8th grade, and again in high school (often junior year) is as clear today as it was to AHA researchers 80 years ago.4

Fig. 9: US History Course of Study by Grade Level and State

The legacy framework for US history is unobjectionable in many regards. Students benefit from repeated exposure to the same historical content, with increasing depth and sophistication, across their K—12 experience.5 The pivot point around the end of Reconstruction is one that few historians would dispute. Still, the structural limits and sequencing quirks of the typical US history course of study often persist without reflection or revision. When reforms do occur, the subject is buffeted by peripheral forces—a new civics requirement, a change in state exam schedules, or the expansion of AP offerings to a wider and younger cohort of students. One concern is the time lapse between students’ experience with the first and second halves of US history, a lag that can last a single summer or as much as six years. In states where only the second half is covered in high school, the events of early American history are stranded in fifth or sixth grade, depriving students of the opportunity for more mature treatment and advanced study of crucial episodes. Meanwhile, second-half history content only grows every year, leaving events of the recent past likely to be crammed in before summer break. In one class document, a teacher had only six class days for a half-century sprint from the Selma to Montgomery marches to Donald Trump’s presidency. Scheduled stops (at the Great Society, Malcom X, Vietnam, Ronald Reagan, 9/11, and Barack Obama) were likely dizzying. Indeed, when surveyed teachers identified the topics where they felt the need for more support, six of the top ten came from the post–civil rights era.6

Despite these difficulties, this model predominates, with 76 percent of surveyed teachers describing their course as chronologically organized. Eighteen percent of surveyed teachers reported that they organize their exposition thematically. We came across few examples of thematically organized curriculum in the materials we collected. When thematic approaches appeared, big questions—about democracy, equality, federalism, labor and business, foreign policy, and civil liberties—seemed well designed for the task. At the level of individual activities, however, the thematic approach can invite anachronism. Asking, for instance, whether James Madison would agree with Barack Obama’s proposal for reforming gun laws may illustrate vividly distinct historical contexts but without an account of how those contexts were produced.7

State Standards and State Agencies

Even though the rise of state social studies standards was historically concentrated at the turn of the 21st century, formats varied; there was no standard for standards. Subsequent professionalization among curriculum specialists built on broad points of consensus, borrowed and referenced standards from other states, and established a set of common patterns. When states and districts offer a rationale for the study of history, preparation for participation in a democratic society is the common refrain. State standards trend toward a definition of social studies that centers inquiry. In addition to being consonant with the various nonfiction reading and writing skills stressed in federal policy, inquiry has been an explicit focus of NCSS, whose 2013 C3 Framework and “inquiry arc” have been widely adopted or cited as reference for recent rounds of standards revision.8.

The influence of the C3 Framework highlights the important role that networks of education professionals (such as teachers, administrators, and publishers) have taken in sustaining a national culture related to social studies instruction. In every state, individual people, not standards documents, carry out the work of developing and aligning curriculum. The work that curriculum leads and supervisors have done to associate with each other, to develop professional norms, and share best practices is how “alignment” actually happens—a fact not generally acknowledged in media coverage of education issues. A great many teachers carry on with minimal awareness of the state agency’s alleged role in their work. Some teachers view it with suspicion or distrust (one referred to the state agency as “the Death Star”), while others look forward to helpful emails from their state social studies specialists promoting professional development opportunities (Table 1).

Table 1: Teacher Commentary on the State Agency and State Standards

| Positive Quotes | Negative Quotes |

|---|---|

| “Standards helped when I started out.” —Alabama teacher | “We have state-level requirements, but I basically ignore them.” —Virginia teacher |

| “We teach the Virginia and US History SOL curriculum, and my school division designs curriculum maps that are helpful for teachers to follow.” —Virginia teacher | “The state standards are really broad. . . . Teachers who don’t have much historical training will look at a standard and not know what they really need to do and are too lax in how they evaluate the kids.” —Colorado teacher |

| “I have them open right here. I use them to make sure I’m hitting everything. They are very helpful—it’s my handbook.” —Alabama teacher | “No contact from or oversight from the state besides the state standards.” —Illinois teacher |

| “Instructional mandates are helpful in that they are pushing us to consider multiple perspectives.” —Illinois teacher | “If I got paid in acronyms, I’d be a rich man.” —Washington teacher |

| “I prefer to be able to link what I’m teaching to a standard.” —Alabama teacher | “The standards are basically useless. . . . If you are a good teacher you are definitely covering all this anyway.” —Connecticut teacher |

| “They reach out to us and we reach out to them. I’m one of the few social studies teachers in the area . . . seeking out PD. . . . I know the AEA person well. . . also met the state [person], she’s good at sending out stuff.” —Iowa teacher | “Just changed buzzwords…I would be lying if I didn’t say we jump through the hoop, it sits on a shelf somewhere so some school board member can look at it if they want to.” —Pennsylvania teacher |

| Great emails about in-service opportunities. . . . They [the state] do as much as they can. —Alabama teacher | “The Washington state standards are garbage.” —Washington teacher |

| “The state standards are stupid. I can’t teach them all—It’s impossible.” —Alabama teacher |

While we refrain from giving letter grades to states on their documents, some state social studies standards do offer clearer guidance than others. Standards documents are artifacts of messy compromises struck among diverse stakeholders across multiple rounds of revision, not necessarily an expression of professional consensus among historians or even of the priorities of history educators. Some documents succeed in wrapping these compromises within a more coherent rhetorical package, while others show traces of disharmony.

Of the many tugs of war apparent within standards documents, the most recognizable is that between content and skills. State standards fall into three categories: skills-focused, content-focused, or a content-skills hybrid. Of the three, the hybrid model is most likely to speak to historians’ preferences. By our count, 10 states emphasize skills to the exclusion of content, nine states hide skills beneath heavier content, and 31 choose a balance.

This research inspired the AHA to revise its official guidance on state social studies standards in 2024, adding new emphasis on the inseparability of factual content from historical thinking.9 This emphasis is neither novel nor controversial. History teachers have long understood the reciprocal notion of teaching “the general concept through the specific fact.”10 Experts as distinct as core content monitor Chester Finn Jr. and inquiry skills booster Kathy Swan have described the phony choice between knowing and thinking.11

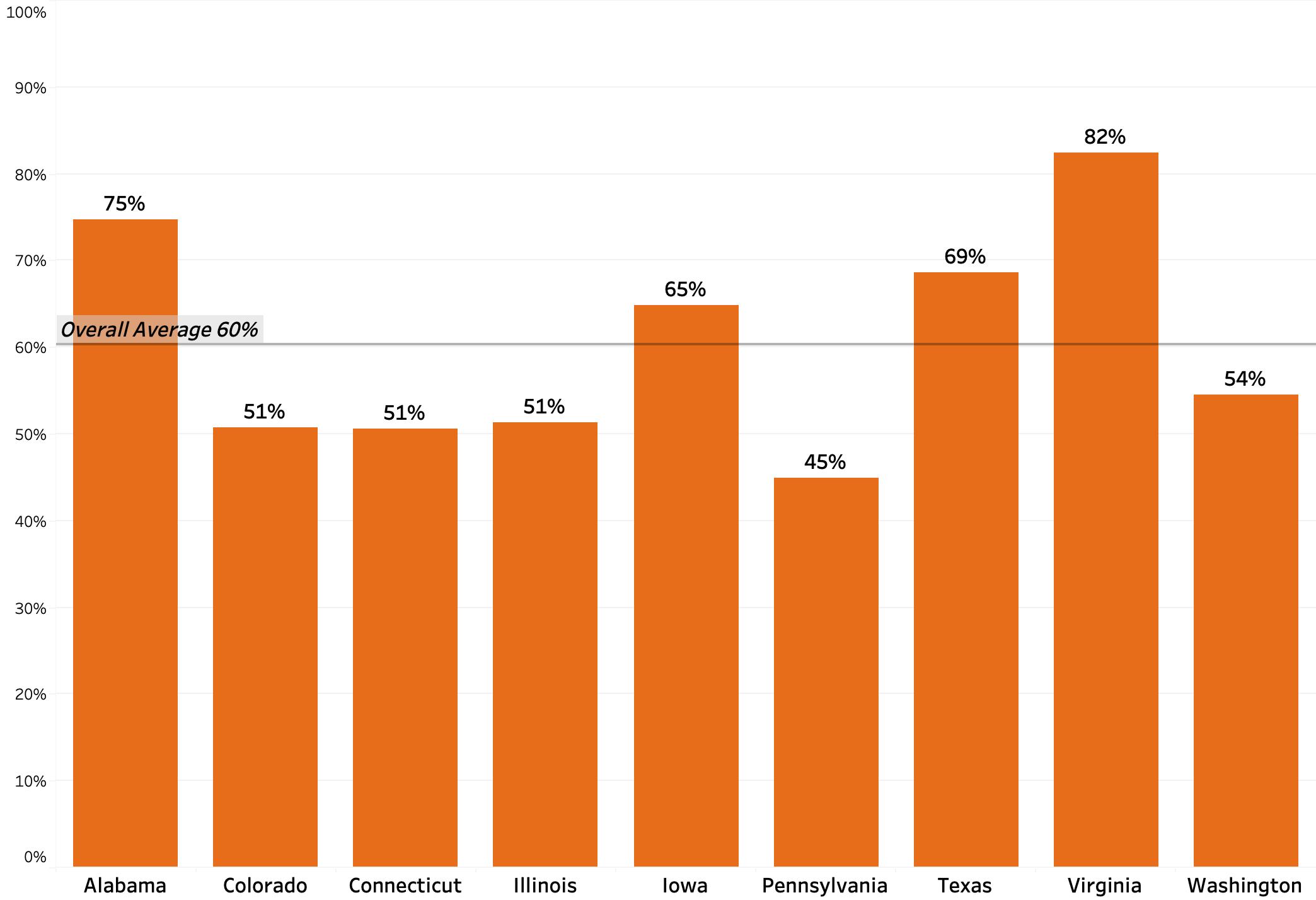

Teachers take notice of the relative strength, clarity, and consequences of academic standards at the state level. Sixty percent of surveyed teachers say they actually use state standards directly in their teaching—although there are important differences from state to state (Fig. 10). Their use as a reference depends on the level of detail in the document as well as the specifics of state assessment and accountability mandates. Among our nine sample states, over two-thirds of teachers in Alabama, Texas, and Virginia report using their state standards, while only half or less in Connecticut, Illinois, and Pennsylvania say the same. New teachers were more likely (65 percent) than veteran teachers (57 percent) to report that they regularly use state standards documents to guide their teaching. Teachers will complain about standards that are too overwhelming in their detailed lists of trivia as well as those that are so broad and abstract that they describe nothing (Table 2).

Fig. 10: Teachers Reporting That They Use State Standards to Teach US History

Table 2: Examples of Social Studies Standards Language

| Tennessee | Illinois |

|---|---|

| The 1920s (1920-1929) | SS.H.2.6-8.LC. Explain how and why perspectives of people have changed over time. |

| Overview: Students will describe how the battle between traditionalism and modernism manifested in the major historical trends and events post-World War I. | |

| US.28 Analyze the impact of the Great Migration of African Americans that began in the early 1900s from the rural South to the industrial regions of the Northeast and Midwest. (T.C.A. § 49-6- 1006) C, E, G, H, T, TCA | |

| US.29 Describe the growth and effects that radio and movies played in the emergence of popular culture as epitomized by celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin, Charles Lindbergh, and Babe Ruth. C, H | |

| US.30 Examine the growth and popularity of country and blues music, including the rise of: the Grand Ole Opry, W.C. Handy, and Bessie Smith. (T.C.A. § 49-6-1006) C, H, T, TCA | |

| US.31 Describe the impact of new technologies of the era, including the advent of air travel and spread of electricity. C, E, H | |

| US.32 Describe the impact of Henry T. Ford, the automobile, and the mass production of automobiles on the American economy and society. C, E, H | |

| US.33 Describe the Harlem Renaissance, its impact, and important figures, including (T.C.A. § 49- 6-1006): Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston. C, H, TCA | |

| US.34 Describe changes in the social and economic status of women during this era, including: flappers, birth control, clerical and office jobs, and the rise of women’s colleges. C, E, H | |

| US.35 Examine challenges related to civil liberties and racial/ethnic tensions during this era, including (T.C.A. § 49-6-1006): First Red Scare, Efforts of Ida B. Wells, Immigration Quota Acts of the 1920s, Emergence of Garveyism, Resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, Rise of the NAACP C, E, G, H, P, T, TCA | |

| US.36 Describe the Scopes Trial of 1925, including: the major figures, two sides of the controversy, the outcome, and legacy. C, H, P, T | |

| US.37 Describe the impacts of Prohibition on American society, including: the rise of organized crime, bootlegging, and speakeasies. C, E, H, P | |

| US.38 Analyze the changes in the economy and culture of the U.S. as a result of credit expansion, consumerism, and financial speculation. C, E, H |

Most standards offer a rationale focused on preparing students for citizenship with critical thinking skills and an understanding of a complex world. As a typical rationale explains, students should “understand America’s past and what decisions of the past account for present circumstances, using historical thinking skills to confront today’s problems, be informed on taking an active position on issues and make sense of the interconnected world around them.”12 While a common ground exists, different political and ideological environments can influence how standards committees and state officials frame their standards. Take the Louisiana state superintendent’s introduction to the 2022 Social Studies standards, in which he underscores the “fragility of liberty” and the mission to “teach our students to appreciate the majesty of our country and their obligations as citizens to safeguard America’s founding principles.”13 Or consider Rhode Island’s 2023 standards, which claim to “validate and affirm individuals’ diverse and intersectional identities,” and help students “critique the world around them . . . and move to act against bias, stereotypes, and inequities.”14 Each of these formulations provides cues for how policymakers expect teachers to read and interpret the specific historical content included in the standards for each grade level.

Partisan differences certainly shape public debates over historical content in state standards. But state agencies in the majority of states roughly agree about which major events and moments constitute the essential history of the nation. In general, standards succeed or fail on the basis of their own organization; consistency, readability, and a moderate level of specificity will often endear them to teachers. New teachers or teachers working in states with fewer resources especially benefit from solid standards that provide a sense of the order and emphasis of historical content within a given class. As a Texas teacher put his view of standards, “I know the way to San Antonio, but it’s nice to have a map.”15

State Assessment

The decisive variable in aligning instructional practice among teachers to any standard, whether issued from the state or the district, is assessment. During the accountability era, assessment mandates landed unevenly and sometimes only temporarily in the social studies world. Bold plans to test everyone on everything were often abandoned before they started. The Keystone Exam in Pennsylvania, for example, has never included social studies content, even though legislators have passed four different laws promising to make it happen.16 As education researchers often lament, assessment requirements are a moving target, with state legislatures and boards of education making new decisions about which tests will be added or dropped from year to year.17

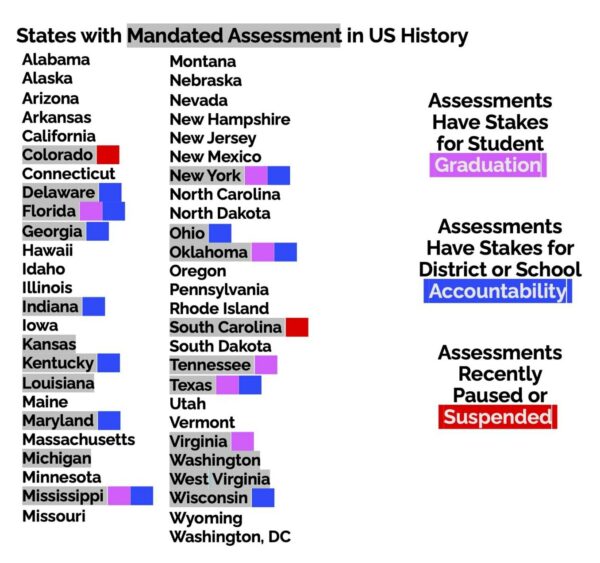

As of 2024, 21 states require some testing in US history, with 10 of those states testing students on history content at least twice over the course of their K–12 experience. A testing requirement does not always equate to a required test, however. In several testing states, assessment instruments are designed and scored locally or chosen from a menu that may include a state-designed test. Some of these assessment mandates are almost purely ceremonial, producing very little record of what was assessed or how students performed. Among states that test, only some could be described as imposing high stakes (for students, for teachers, for school districts) to their testing requirements (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11: States with Mandated Assessment in US History

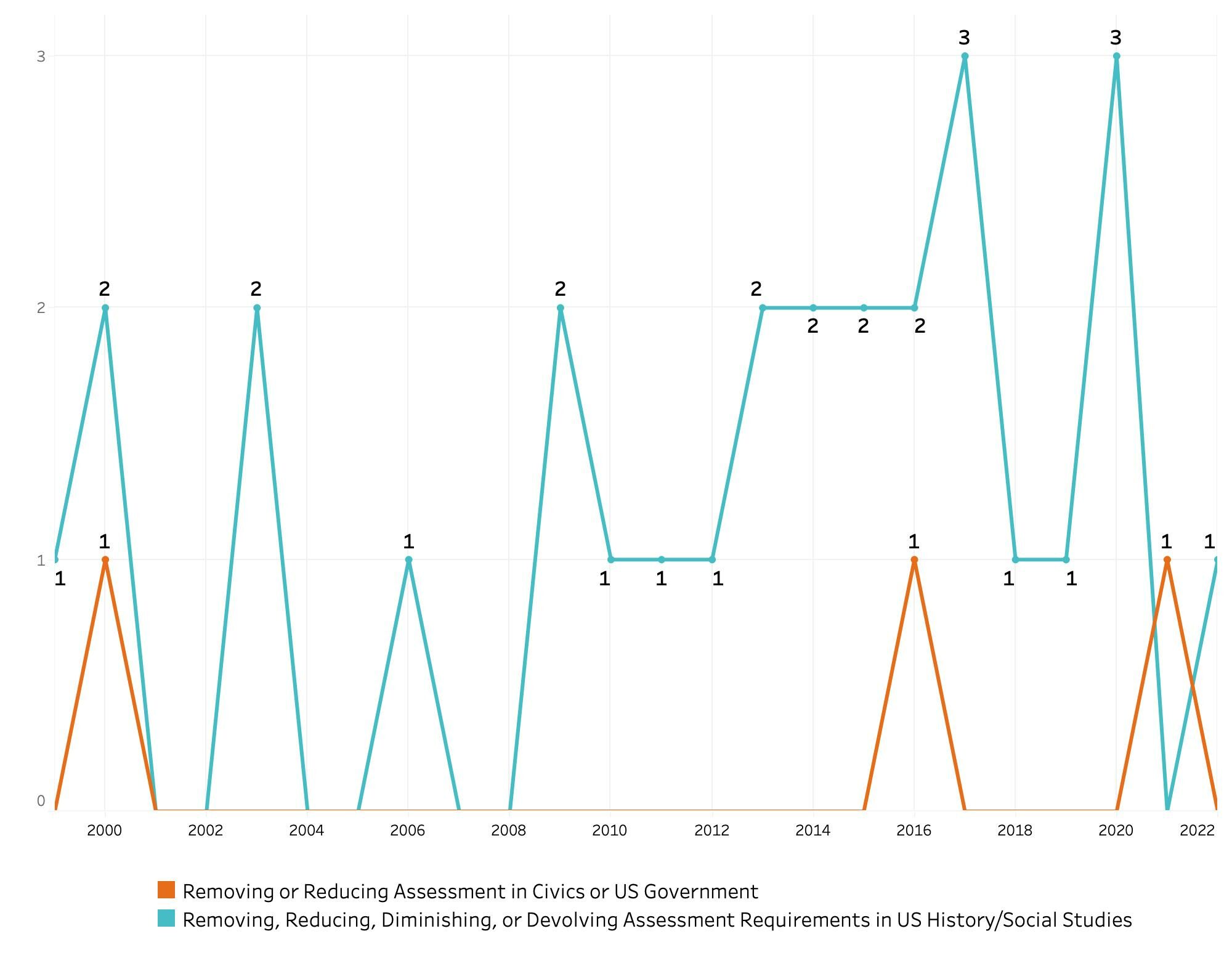

Despite a blip of enthusiasm for civics testing in the 2010s, the general trend is away from standardized testing in social studies, with a number of more recent laws scaling back or removing assessment mandates (Fig. 12).18 Accountability rituals have been slow to reassert themselves following the interruption of the COVID-19 pandemic or have reemerged in less rigid forms.19

Fig. 12: State Laws Reducing Assessment Mandates in US History, Social Studies, and Civics, 1999–2022 (n = 33)

Teachers give mixed signals about history’s position in the accountability landscape. In interviews, teachers consistently cite social studies’ low priority status (as compared with more frequently tested subjects) as a source of frustration, using phrases like “back burner” and “afterthought.”20 Teachers in states without state social studies testing even wished that history would be tested, if only to boost its status and instructional time with their administrators.21 As one Pennsylvania teacher put it, “I’m not a fan of standardized testing, but there is some benefit to having it.”22

When states do mandate and administer a common testing instrument, assessment cuts recognizable patterns across the curricular and labor landscape. Teachers in Virginia were far more likely to cite the state’s Standards of Learning (SOLs) as something that drives their teaching (83 percent) than teachers elsewhere (average of 58 percent across the other eight sample states). Virginia teachers were also more likely to describe the state standards as having more decisive power over their curriculum than district directives. As one teacher explained, “Our state specifies the content of the curriculum; our district doesn’t really do that.”23 Plenty of other Virginia teachers described a role at their district office, but as another teacher explained, “you can teach what you want at whatever pace you want, but if your [SOL test] scores are consistently low, you may be looking for another job.”24

In Texas, our sample state with the most detailed standards (the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS), the most unified assessment regime (the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or the STAAR test), and the highest-stakes accountability system (the Texas Academic Performance Reports, or TAPR), the trickle-down effects of testing were even more apparent. District-produced documents and in-use curricula showed a great deal of consistency and were far more likely to make itemized reference (or even direct repetition) of state standards language than in other states. The TEKS and the STAAR test indeed shape important Texas-specific practices: the comprehensive statewide resources produced by the Texas Curriculum Management Program Cooperative (TCMPC); the enhanced role of district-level curriculum coordinators; the high frequency of common benchmark unit tests for grade-level course teams; specialized test-prep vendors; and the sense of pride that some teachers and administrators take in delivering high scores every spring. One teacher recalled feeling charged with energy when he saw his middle-class school’s scores approach those of the wealthier school in the district: “we wanted to beat them and win.”25 A suburban administrator described his approach to managing his teachers in similar terms: “I’m super competitive, and I want us to be the best.”26 Not all teachers respond positively to the competitive conditions set by testing, with some likening their context to “a factory. . .[where] we’re turning out a product.”27 Whether teachers find themselves buoyed or burdened by statewide assessment and accountability mandates, testing remains the key point of leverage for state agencies as enforcers of state standards.

State Legislation

Caveats about loose coupling and local control notwithstanding, what happens in the schoolhouse often begins in the statehouse. In order to track historical and regional patterns of lawmaking related to US history education, we visited the digital archives of all 50 state legislatures and assembled a database of 808 individual legislative acts passed between 1980 and 2022. The database is extensive but likely not exhaustive with regard to every relevant mandate, and it can speak only to the activities of state legislatures (as opposed to the actions of State Boards of Education). Still, this large corpus affords a view of identifiable trends, waves, and swings of attention paid and emphasis given to the topic of US history education by American state lawmakers. In many cases, swells of state legislative activity synchronize with federal priorities and national education reform fashions (as with the rise in standards-making and assessment mandates straddling the turn of the 21st century or the swell of new civics mandates in the 2010s). On other topics, lawmakers respond to hyperlocal concerns, state-specific constituencies, or bigger civic and popular history media events. Figures of local history and folklore earn mention as namesakes for special days or weeks of topical study: Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass in Maryland; John Henry in West Virginia; George Rogers Clark in Indiana; Harvey Milk, Ronald Reagan, and Larry Itliong in California; cowboys and cowgirls in Wyoming.28 Laws encouraging the study of Hispanics in American history cluster primarily in states with histories of Spanish colonization or Latin American immigration.29 Mandates to cover Francophone heritage are on the books in Louisiana, Vermont, and Maine.30 Holocaust education laws appeared earliest in states with established Jewish populations and alongside the opening of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the release of the film Schindler’s List, both in 1993.31 Three states have an Amistad Commission on African American history that originated around the release of the 2002 film Amistad.32 A 2001 New Jersey law requiring Italian American history seems to have been designed in part as a counterweight to ethnic depictions on The Sopranos.33

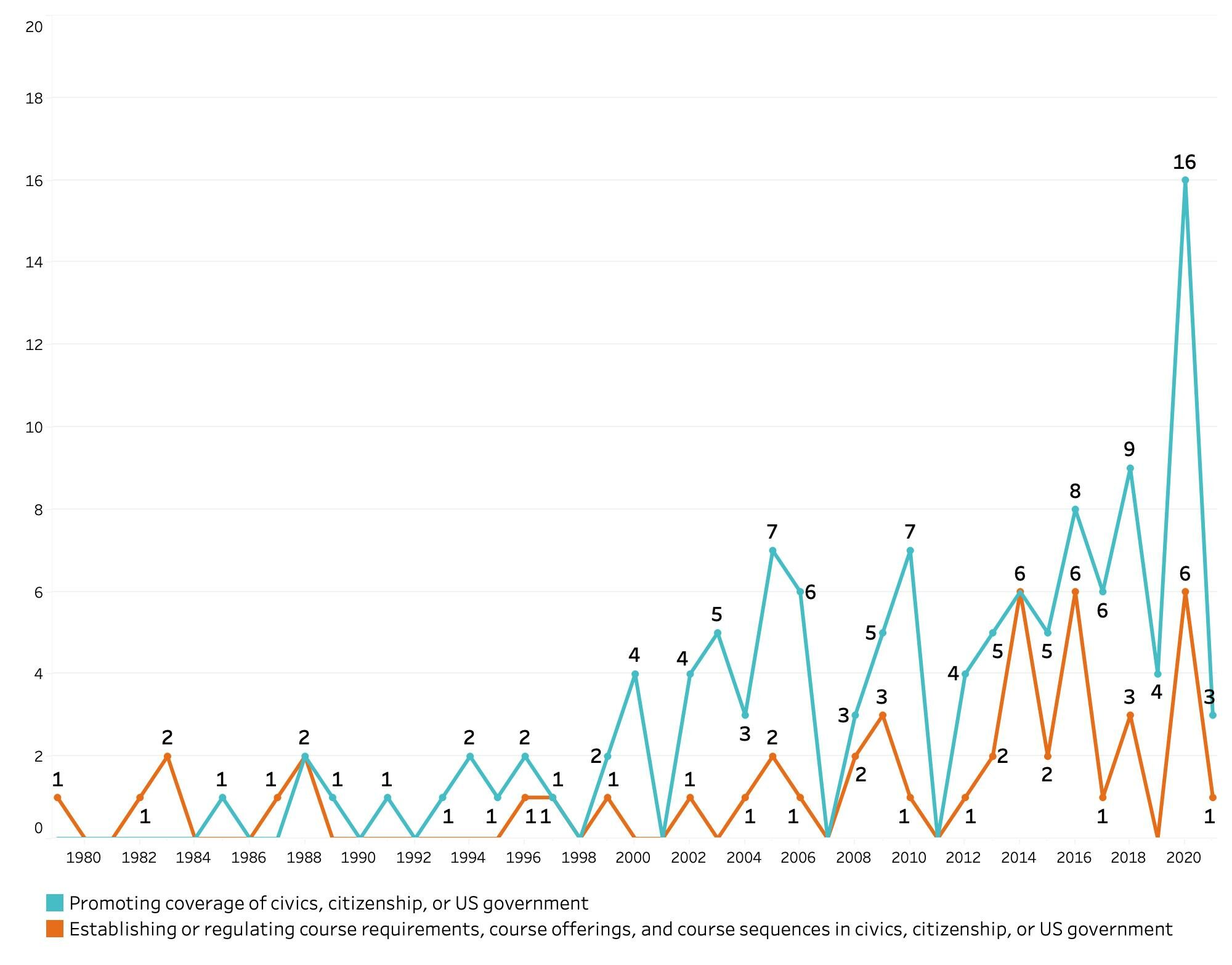

Given our primary research questions, we were particularly interested in those legislative mandates that sought to assert state control over elements of curricular content—whether by initiating new testing and accountability procedures for social studies, by prescribing a certain topic or tone regarding American history, or by addressing the state’s role in instructional materials. The spikes in new legislation related to requirements and assessment in civics in the mid-2010s and in 2021 (Fig. 13) followed an organized push by civics nonprofits, including a model legislation lobbying drive requiring that students be tested using the citizenship naturalization test.

Fig. 13: State Legislative Activity Promoting Civics Content, Coursework, and Assessment, 1980–2022 (n = 173 instances across 146 distinct laws)

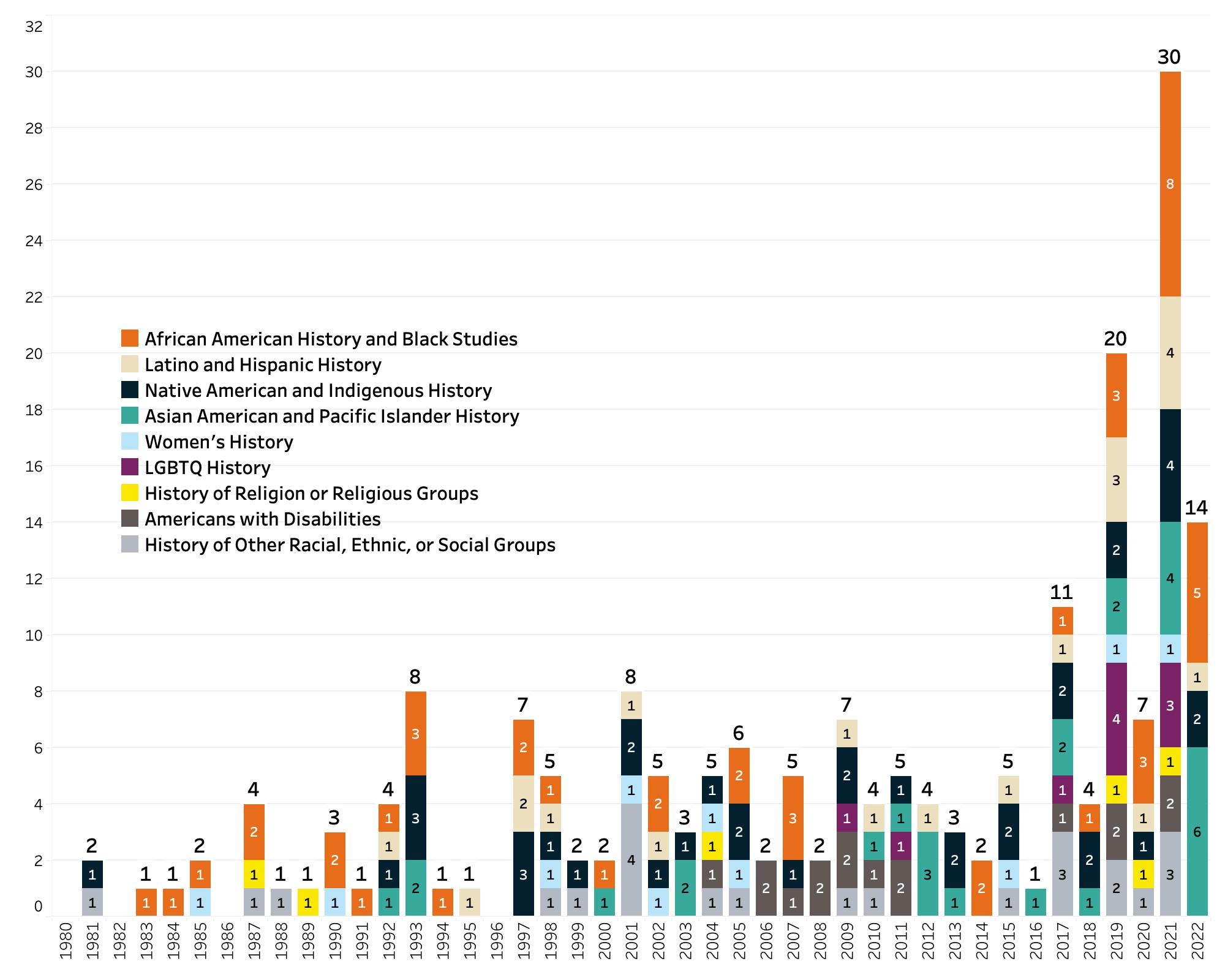

There’s also the much longer and quite widespread effort to incorporate diversity—namely the notion that the narrative of American history should incorporate stories from multiple perspectives, inclusive of the various groups that constitute the national population. Across our existing database of laws, we have identified 199 separate instances between 1980 and 2022 of state legislatures requiring that specifically named groups be accorded coverage in US history curriculum (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14: State Legislative Activity Promoting Social Studies Coverage of Diverse Groups, by Group and by Year, 1980–2022

The route and rationale for the inclusion of various subgroups of Americans in state laws has varied across time and across states. In some cases, routes to inclusion came by way of an ever-expanding list of “contributions” by subgroups. A 1967 Illinois law requiring US history classes to cover “American Negroes” and 12 European ethnic groups has since been added to multiple times, with women, Hispanics, labor unions, LGBT Americans, religious groups, and people with disabilities earning a mention in the school code.34 California, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, and Washington stand out as producing high levels of legislated directives related to the coverage of specific groups.

In other states, space for subgroups has been opened with direct reference to histories of exclusion, oppression, or atrocity. The mold for this approach was cast by the most frequently mentioned atrocities in state law: the Holocaust and American slavery. Twenty-nine states passed laws requiring or promoting the study of the Holocaust and genocide, while nine require the specific study of slavery and emancipation. Laws mandating the study of the Irish Famine, the Armenian genocide, Italian fascism, or the deportation of Mexicans during the Great Depression have made their case with reference to, or even as addenda to, existing laws mandating the study of slavery or the Holocaust.35 In some instances, a legislative initiative on behalf of one group became a model for another. In New York, a law mandating Holocaust and slavery education in 1993 was followed in 1995 by a law requiring the study of the Irish Famine, another in 1997 to include study of the Underground Railroad, and the formation of the Amistad Commission to survey and develop curriculum on slavery in 2005.36 In California, the legislature expanded required study of the Vietnam War to include Asian and Asian American groups and incorporated the Bracero program into legislative mandates on the study of World War II.37

Sometimes, policy initiatives without an explicit social studies content agenda have expanded into curricular mandates. In New Mexico, legislative attention to bilingual schoolchildren in the 1970s paved a route for a cascade of multicultural educational programs, including coursework in Native and Hispanic studies.38 In other instances, concerns about concentrated disadvantage among certain students have underwritten curricular focus on an ethnic history. Lawmakers in Washington state originally justified their call for coursework on Native American history by pointing to dropout rates and low academic achievement among American Indian students.39 Subsequently, these initiatives have grown into the nation’s most extensive state-developed curriculum on tribal history, culture, and government.40

State legislators have targeted US history course requirements as the vehicle for other political signals, sometimes sparring along ideological lines. Seven states have laws requiring the history of labor unions; seven others have named “free enterprise” as a theme to be emphasized in the study of American history. More widespread is a reverence for the nation’s founding documents, with 32 states requiring that certain works of civic scripture (typically the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights) be studied. Divergent ideological emphases may end up combined into an initiative once established. A special Colorado commission on the “Inclusion of American Minorities” and “the intersectionality of significant social and cultural features” was amended to tag on a traditional list of founding documents.41

Specific encouragement by lawmakers unexpectedly includes at least 13 separate calls for the use of oral history resources in instruction, most often from military veterans.42 State legislatures are particularly fond of designating specific times of year (holidays, weeks, or months) as moments for concentrated study or appreciation of a particular historical event, theme, group, or person. We have found 79 of these laws scattered throughout the nation, passed between 1980 and 2022. While some mark important historical events and figures, the laws’ insistence that study coincide with a civic calendar, rather than the chronological pacing of a typical US history course, seems likely to encourage a series of ceremonial non sequiturs, rather than a historical exploration of context and significance.

State legislators’ many gestures toward US history instruction have clustered into discernable patterns along the historical timeline, but their influence on local curricular decision-making has been uneven. More recently, some lawmakers and state agency officials appear to have realized that legislated content mandates can be paired with standards revisions and funding for model curricula and professional development to leverage more influence over local instructional decisions. In Connecticut, Illinois, and Washington, all states with strong traditions of local control, laws enacted in the past decade have begun to assign more substantive curricular tasks to the state education agency on select topics of US history. A 2015 law in Washington required all districts to use state-developed resources on Native American history (which later developed into the Since Time Immemorial curriculum) and to consult with local federally recognized tribes in order to teach about Native history and tribal sovereignty.43 Since 2020, Connecticut has mandated that the new Black and Latino studies high school elective would be the first and only course taught using a state-designed common curriculum.44 A series of inclusive history mandates in Illinois—mandating study of LGBTQ history in 2019, requiring expanded treatment of Black history in 2021, and mandating study of Asian American history also in 2021—authorized the state agency to set up new a statewide commission, nonprofit partnerships, and professional development grants to promote uptake of the new mandates.45

No amount of analysis of state mandates, however, will indicate much about how history is actually taught. Local district contexts—regarding who is in charge, how teachers work together, and what materials are in use—are where the action is.

← Part 1: Contexts Part 3: Curricular Decisions →

Notes

- Quotes come from Paul E. Lingfelter, “It’s Time to Make Our Academic Standards Clear,” Viewpoint, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (May 2011); Kenneth K. Wong, “Federalism Revised: The Promise and Challenge of the No Child Left Behind Act,” Public Administration Review (December 2008): S175–85; John W. Meyer, W. Richard Scott, David Strang, and Andrew L. Creighton, “Bureaucratization without Centralization: Changes in the Organizational System of American Public Education, 1940–1980,” in Institutional Patterns and Organizations: Culture and Environment, Lynne G. Zucker, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 1988), 140–67; Gail L. Sunderman, Ben Levin and Roger Slee, “Evidence of the Impact of School Reform on Systems Governance and Educational Bureaucracies in the United States,” Review of Research in Education 34, no. 1 (2010): 226–53; Edward Crow, “Measuring What Matters: A Stronger Accountability Model for Teacher Education,” Center for American Progress, 2010; Morgan Polikoff, Beyond Standards: The Fragmentation of Education Governance and the Promise of Curriculum Reform (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2023), 12; Dara Zeehandelaar and David Griffith, “Schools of Thought: A Taxonomy of American Educational Governance” (Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2015). [↩]

- See Paul Manna, School’s In: Federalism and the National Education Agenda (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2007) 6–7. [↩]

- There is some variation in the end points applied to mark first and second parts of US history. In the 5th grade, a significant number of courses end around 1800, while Massachusetts’s 5th grade course goes to the Civil War and then jumps to the Civil Rights Movement. In acknowledgment of its own history, West Virginia has a state and US history course that goes from the Civil War to the early 20th century. In middle school, there are a few outliers as well. Some Pennsylvania districts cover two separate courses divided at 1914, while Arkansas splits the course at 1930. Washington offers a primarily 19th-century course, Kansas goes to 1900, and Illinois has a course from 1858 to the present. In high school, Arkansas picks up in 1929, and the courses in Maryland, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania begin around the late 1890s. In Washington state, the focus is primarily on the 20th and 21st centuries, whereas Oklahoma starts from the Civil War instead of Reconstruction. [↩]

- “American History in the Classroom,” chapter 3 in Edgar B. Wesley, committee director, The Report of the Committee on American History in Schools and Colleges of the American Historical Association, the Mississippi Valley Historical Association, and the National Council for the Social Studies (New York: Macmillan, 1944), https://www.historians.org/resource/chapter-3-american-history-in-the-classroom/. [↩]

- On spiraled curriculum, see Jerome S. Bruner, The Process of Education (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960), 33–54. On the challenges of integrating learning science into teacher preparation, see Daniel Willingham, “A Mental Model of the Learner: Teaching the Basic Science of Educational Psychology to Future Teachers,” Mind, Brain, and Education 11, no. 4 (December 2017): 166–75. [↩]

- “Survey of US History Teachers,” AHA/NORC questionnaire, 2023, question 22. [↩]

- “Thematic US History, 2022–2023: Summit Portfolio,” district document, Illinois, Suburb: Large, (2022). [↩]

- In 2017, the Brookings Institution counted 23 states that incorporated the NCSS C3 Framework into either standards or frameworks. Michael Hansen, Elizabeth Mann Levesque, Jon Valant, and Diana Quintero, “2018 Brown Center Report on American Education: An Inventory of State Civics Requirements,” Brookings Institution, accessed December 15, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/2018-brown-center-report-on-american-education-an-inventory-of-state-civics-requirements/. By our count, six states cite C3 as their primary model, nine mention C3, and another 12 show evident but uncited influence. In 2017, Vermont forewent adopting academic content standards, adopting the C3 Framework itself. [↩]

- Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke, “What Does It Mean to Think Historically,” Perspectives 45, no. 1 (January 2007), https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/what-does-it-mean-to-think-historically-january-2007/. As a discipline, history depends at a fundamental level on a set of core concepts that encompass both content and analysis. Conceptual frameworks at the core of history highlight connections between social, cultural, economic, technological, and political factors and changes in human experience. These disciplinary concepts also address how historians apply analysis to refine an interpretation, including context, change, and continuity; the ability to access, interpret, and apply evidence from historical documents; and the ability to evaluate different historical perspectives and interpretations. [↩]

- Mary Sheldon Barnes, “General History in the High School,” The Academy: A Journal of Secondary Education 4, no. 5 (June 1889), 286. [↩]

- See Finn and Ravitch, What Do Our 17-Year Olds Know, 9; Swan in “Ten Years of C3: The Past, Present, and Future of State Standards” (video recording), AHA, November 15, 2023, https://youtu.be/QHTcdMG_YZM. [↩]

- Kentucky Department of Education, Kentucky Academic Standards for Social Studies (2022), 2. [↩]

- Louisiana Department of Education, Louisiana Social Studies Standards (2022), 1. [↩]

- State of Rhode Island Department of Education, Rhode Island Social Studies Standards (2023), 7. [↩]

- Interview with high school teacher, HST 729, October 24, 2023. [↩]

- See Pennsylvania HB 1901 (2012); HB 564 (2018); SB 1095 (2018); SB 1216 (2020). [↩]

- S. G. Grant and Cinthia Salinas, “Assessment and Accountability in the Social Studies,” in Handbook of Research in Social Studies Education, Linda S. Levstik and Cynthia Tyson, eds. (New York: Routledge, 2008), 220. [↩]

- For example bills illustrating the wave of reduced assessment requirements, see Ohio HB 555 (2012); California AB 484 (2013); Indiana SB 62 (2015); Louisiana HB 616 (2017); Pennsylvania SB 1095 (2018); North Carolina SB 621 (2019); Georgia SB 367 (2020). [↩]

- See, for example, Erica Breunlin, “Colorado Democrats Want to Ax Social Studies from State Standardized Tests. Here’s Why,” Colorado Sun, January 27, 2023, coloradosun.com/2023/01/27/social-studies-standardize-testing-colorado/; Colorado SB 23-061 (2023), https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb23-061. [↩]

- For “afterthought”: Interview with high school social studies teacher (HST 731), November 6, 2023; Interview with middle school social studies teacher (MST 731), September 13, 2023. For “back burner”: Interview with high school social studies administrator (SSA 406), April 21, 2023; Interview with middle school social studies teacher (MST 422), June 1, 2023; Interview with middle school social studies teacher (MST 422), June 1, 2023. [↩]

- Interview with high school teacher (HST 614), September 19, 2023; Interview with social studies administrator (SSA 615), October 17, 2023. [↩]

- Interview with high school social studies teacher (HST 401), April 20, 2023; Interview with high school social studies teacher (HST 614), September 19, 2023. [↩]

- Rural Virginia Teacher, “Survey of US History Teachers,” AHA/NORC questionnaire, 2023, question 6. [↩]

- Rural Virginia Teacher, “Survey of US History Teachers,” AHA/NORC questionnaire, 2023, question 6. [↩]

- Interview with middle school social studies teacher (MST 720), June 26, 2023. [↩]

- Interview with social studies administrator (SSA 712), February 28, 2023. [↩]

- Interview with high school social studies teacher (HST 720), June 20, 2023. [↩]

- See Maryland SB 879 (2019); West Virginia HB 4491 (2000); Indiana HB 1228 (1975); California SB 572 (2009), SB 944 (2010), and AB 7 (2017); Wyoming HB 130 (2019). [↩]

- States with laws on the books regarding Hispanic and Latino history include California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, and Utah. [↩]

- Louisiana RS 17-272 (1968); Vermont R-5 (1981); Maine HP 0310 (2009). [↩]

- The earliest states with Holocaust education commissions or mandates were California (1985), Ohio (1987), Illinois (1989), New Jersey (1991), New York (1993), Florida (1994), Connecticut (1995), Pennsylvania (1996), and Tennessee (1996). For a deeper history of Holocaust education in the United States, see Thomas D. Fallace, The Emergence of Holocaust Education in American Schools (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). For a wider cultural history, see Peter Novick, The Holocaust and American Life (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999). On reception and influence of Schindler’s List, see Alan Mintz, Popular Culture and the Shaping of Holocaust Memory in America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 125–58. [↩]

- Amistad Commissions were established in New Jersey (2002), Illinois (2005), and New York (2005). [↩]

- New Jersey NJA 3963 (2001). [↩]

- Illinois Compiled Statutes (105 ILCS 5/) School Code, (from ch. 122, par. 27-21). [↩]

- California AB 146 (2015); Rhode Island HB 7397 (2000). [↩]

- New York SB 7765 (1993); AB 6510 (1995); AB 8458 (1997); BA 6362-B (2005). [↩]

- California AB 78 (2003); AB 895 (2018); SB 993 (2012). [↩]

- Mariela Nuñez-Janes, “Bilingual Education and Identity Debates in New Mexico: Constructing and Contesting Nationalism and Ethnicity,” Journal of the Southwest 44, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 61–78. [↩]

- Washington HB 1495 (2005); SB 5973 (2009). [↩]

- See Washington SB 5433 (2015) and “John McCoy (lulilaš) Since Time Immemorial: Tribal Sovereignty in Washington State,” Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, https://ospi.k12.wa.us/student-success/resources-subject-area/john-mccoy-lulilas-time-immemorial-tribal-sovereignty-washington-state. [↩]

- Colorado HB 19-1192 (2019); SB 21-067 (2021). [↩]

- See, for example, California AB 2003 (2002) on oral histories in Holocaust and genocide instruction; AB 146 (2015) on oral histories of unlawful deportations of Mexican Americans during the Great Depression; and SB 895 (2018) on oral histories of Vietnam War refugees and Cambodian genocide survivors. Florida HB 5 (2021), or the “Portraits in Patriotism Act,” requires the State Board to “curate oral history resources . . . which provide portraits in patriotism based on the personal stories of diverse individuals who demonstrate civic-minded qualities, including first-person accounts of victims of other nations’ governing philosophies who can compare those philosophies with those of the United States.” [↩]

- Washington SB 5433 (2015). [↩]

- Connecticut Public Act 19-12 (2020). [↩]

- Illinois HB 246 (2019); HB 2170 (2021); HB 376 (2021). See also “The Inclusive American History Commission Final Report: Pursuant to PA 102-0209,” Illinois State Board of Education (2022), https://www.isbe.net/Documents_IAHC/Inclusive-American-History-Commission-Report.pdf; Communications Office, University of Illinois College of Education, “Faculty Viewpoint: Leading Inclusive, Inquiry-Based Teaching and Learning,” May, 24, 2022, https://education.illinois.edu/about/news-events/news/article/2022/05/24/faculty-viewpoint-leading-inclusive-inquiry-based-teaching-and-learning. [↩]