Contents

Research Questions

Methods and Samples

Historical Antecedents

Research Questions

Well before the AHA initiated this research, various public figures already had claimed to have answered its underlying questions. In one camp were political progressives, whose response to the election of President Donald Trump in 2016 included calls to confront the social bases of racism and reaction in American politics.1 In some cases, these calls revived a perennial critique: that K–12 US history curricula instilled a triumphal fable about the nation, insufficiently revised to reflect more critical scholarship and unreflective of a racially diversifying cohort of school-aged Americans. Journalists like those helming the New York Times Magazine’s multistage 1619 Project led with headlines that schoolchildren were being subjected to “educational malpractice” for having not been taught the “fuller truth” about slavery and racism.2 The project’s designers and contributors asserted at its rollout in 2019 that centering race, slavery, and resistance would contextualize contemporary political concerns.3

Media coverage of products like the 1619 Project spurred countervailing claims by political conservatives that patriotic education was in urgent need of restoration.4 The Trump presidency already had struck a restorationist and nationalistic pose, promising a celebration of American heritage that would turn back the tide of liberal critique and splintered identity.5 A unique context in the spring and summer of 2020—the combination of a pandemic lockdown, a presidential campaign, and widespread unrest related to racial injustice—kindled new initiatives. As Trump declared in an Independence Day address at Mount Rushmore, “our children are taught in school to hate their own country.”6 The president’s hastily assembled 1776 Commission promised to cut through the “twisted web of lies in our schools and classrooms.”7

For activists answering Trump’s alarm bell, unpatriotic curriculum was the tip of the iceberg; beneath the surface was a divisive “default operating ideology” that had drifted from the academy to the schoolhouse.8 Conservative strategists christened the iceberg “critical race theory” (CRT) and launched a legislative icebreaker in March 2021 to ban the teaching of “divisive concepts.” By the end of that year, lawmakers in 22 states had introduced 54 bills in the anti-CRT mold, passing 12; by the end of 2022, 137 more bills had been introduced, with a total of 41 states considering an anti-CRT initiative. By 2023, the panic had slowed, and only two bills passed explicitly related to history education.9

Hyperpartisan politics added fuel to ongoing debates at the local, state, and national level about the teaching of US history. Were American schoolchildren, as some on the left feared, experiencing an uncritical, triumphal US history education in which teachers kept slavery and racism away from the center of the American story? Or, as right-wing activists asserted, had partisans of critical race theory captured the education state to present an explicitly negative view of the nation?

AHA researchers immediately realized that two straightforward facts rendered sweeping generalizations about whitewashed history and brainwashed students implausible. The chasm between curriculum as written and the curriculum as taught—the difference between the recipe and the meal—obscures what actually happens in American classrooms.10 In addition, the devolved structures of governance and loosely coupled systems of management preserve local control of most aspects of education.11 Something like nutrition recommendations (state standards) are put to paper and given the force of law in all 50 states, but the quality of raw ingredients varies widely, and recipes (curricular materials) are cobbled together across a vast, localized landscape of independent kitchens. Decisions about what should be served to students reside with multiple actors: school boards and district staff across more than 13,000 districts; principals, department chairs, and course teams in over 90,000 public schoolhouses; and the individual social studies teachers responsible for delivering lessons in every history classroom.12

To reflect the complexity of curricular decision making in the United States, our opening question—What are American middle and secondary school students taught about US history?—spurred two follow-ups:

- Who decides what is taught in US history?

- What sources, texts, and materials do teachers actually use when they teach US history?

Our work follows in the footsteps of multiple research teams that have sought to map the social studies landscape.13

In the 21st century, the Fordham Institute has been the most prominent and prolific, issuing five report cards on the quality of US history and civics standards since 1998.14 In 2003, the AHA and the Organization of American Historians (OAH) conducted a national survey, assessing teacher qualifications, academic standards, assessment, and graduation requirements for social studies.15 With a focus on geography, the Grosvenor Center for Geographic Education at Texas State University has conducted a survey of state requirements every year since 2009.16 Most recently, the American Institutes for Research (AIR) assembled a digital interactive dashboard of state standards, disciplinary coverage, graduation requirements, and assessment mandates.17 Meanwhile, an array of other organizations have conducted targeted reviews of state standards and available curricula on selected topics in American history and civics.18

This report breaks new ground by capturing conditions across three levels of curricular decision-making: the state, the district, and the teacher. By exploring the relationships among these levels, including the power each wields and the resources they can draw upon, this comprehensive report explains how history curriculum is enacted in the United States.

Methods and Sample

With American educational policymaking diverse, devolved, and divided, we were especially interested in capturing a range of environments, both among states and within them. For state standards, graduation requirements, and state legislation, we covered the entire nation. As we moved into the details of state rulemaking, district guidance, and teacher choices, we chose nine states as the field sites for our survey, interviews, and collection of curricular materials. Each of the selected states—Alabama, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Washington—represents one of the nine regional divisions used by the US Census and provides a mix of political, administrative, and social contexts affecting education. (For an extended discussion of politics, state agency authority, social studies assessment, and labor and licensure rules within these nine states, see Appendix 1.)

The State

Consequential decisions about what students will learn have increasingly been taken up by state departments of education. Indeed, the early 21st-century expansion of federal involvement in education was preceded and enabled by the late 20th-century growth of state education agencies (SEAs). Civil rights mandates in the 1960s, suits regarding disability law and school finance in the 1970s, and the assessment and accountability movement in the 1980s and 1990s all strengthened the hand of SEAs over schooling in the United States.19

Today, state boards of education typically adopt academic standards, staff SEAs with curriculum specialists, and in some cases enact assessment and accountability regimes or rules for statewide adoption or approval of instructional materials. State legislatures frequently pass laws mandating that SEAs regulate graduation requirements or assessments in social studies, mandate new course offerings, or specify content coverage. State lawmakers also have repeatedly chosen social studies and US history instruction as a place in school codes to leverage moral authority, comment on issues of civic import, or recognize advocacy by particular constituencies. In practice, state authority is alternately constrained and empowered by a dynamic interpenetration of local operational control, federal requirements and incentives, and networked professional associations and interest groups—any one of which individual school teachers can, and often do, ignore.

Without standardized assessment, state agencies have limited leverage over local curricular decisions. To learn how these trends and conditions have affected the state’s role in US history curricula, the AHA appraised state standards in US history in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, conducted surveys and interviews with state curriculum specialists, compared courses of study and assessment regimes nationwide, and assembled a 50-state database of 877 distinct pieces of legislation related to US history education, primarily over the last 40 years.20

The District

State-level documents are ultimately a poor proxy for an understanding of in-use curriculum. Teachers can do excellent work in states with weak or incoherent standards, and history can be taught poorly in states with carefully written state documents. Even in states with highly specific standards, state-mandated common exams in US history, and a robust administrative apparatus, questions about what instructional materials will be used and how topics will be taught will almost always be answered locally. Some school districts—or local education agencies (LEAs)—have the capacity and ambition to answer these questions in great detail, with intricate curriculum maps, pacing guides, unit plans, common assessments, and a suite of purchased resources aligned to state standards. These districts may task a designated social studies coordinator, curriculum specialist, or instructional coach with rituals of alignment and oversight, revising materials in sync with state standards or convening teachers in course level teams in ongoing cycles of data analysis and curricular development.

In most districts, however, layers of social studies staffing and official documentation of US history curricula simply do not exist. What is taught rests with the teachers who teach the course—sitting in binders, digital cloud storage, or in their heads. Even in districts where an administrative ecosystem of subject-specific curriculum coordinators has been allowed to grow, expectations of district-wide fidelity to official priorities are rare in the absence of common assessment.

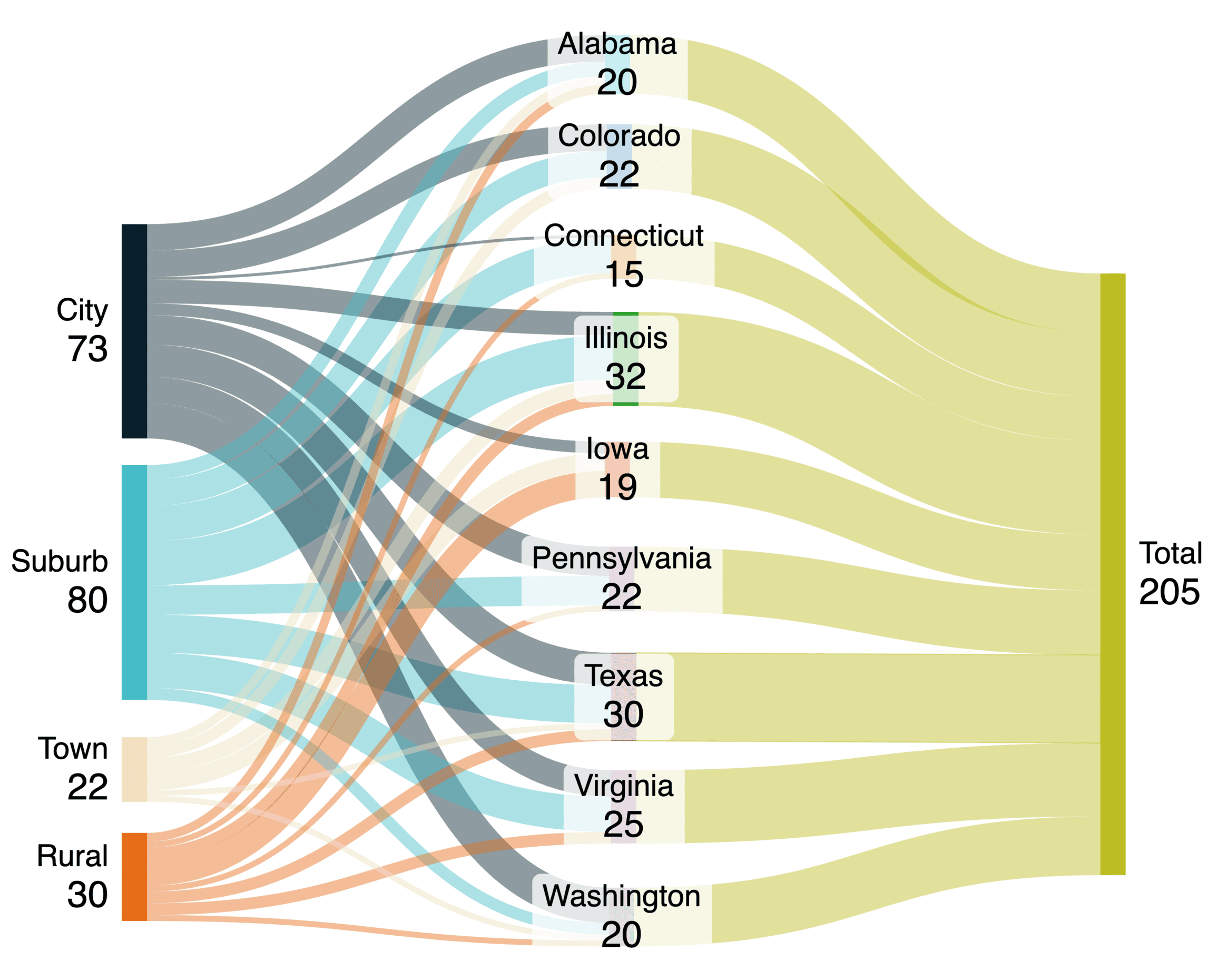

To gain a view of these dynamics, we interviewed educators (147 teachers and 58 administrators) across our nine sample states.21Interview subjects were recruited in a multistage process, leveraging contact lists and social media networks from the AHA, the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS, a project partner), National History Day, the National Council for History Education, and the Council of State Social Studies Supervisors. After exhausting these contacts, we sent email solicitations directly to social studies teachers in states and locale types that were at that point underrepresented. Once the survey instrument was in the field, we increased our pool of interview participants by allowing survey respondents to opt in to a follow-up interview by way of a link at the conclusion of the questionnaire. Hour-long interviews followed a standardized, semistructured format and were conducted over Zoom between August 2022 and February 2024. Interviews explored teachers’ interests in history, their views of managerial dynamics in the school and district setting, the instructional resources and professional development providers that they trust, and the moments of challenge that they encounter from students, parents, and community members. (See Appendix 2 for the release form and questionnaire.) We paid special attention to capturing a mix of social and political environments within each sample state, with 39 percent of interviewees from suburbs, 36 percent from cities, 15 percent from rural locales, and 10 percent from towns (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Interviewees by State and Locale Type (n = 205) (Made at SankeyMATIC.com)

To appraise historical content, we needed instructional materials. Our most reliable collection method was to ask interview subjects to provide what they used. Most teachers were happy to share, as were many administrators. Elsewhere, curricular paperwork and instructional resources were found on district websites. In some places—when administrators expressed concerns about copyrighted materials or where political pressure had left district officials fearful of public scrutiny—we encountered evasions or refusals. When needed, we sent Freedom of Information requests, some of which were efficiently and thoroughly honored, while others idled or resulted in only the broadest outlines of course topics.

Because there is no standard unit of paperwork used by all teachers or administrators, we appraised materials across a broad spectrum of formats. We took anything we were given, so long as teachers used it or were told to use it. Analysis across a range of formats proved challenging—not even a comparison of apples to oranges, but apples to elephants. Our collection came to include everything from district-issued curriculum maps to course-team performance assessments to published lesson plans to entire LMS course modules to personal PowerPoints to lists of primary sources. This archive of curricular materials represents in-use documents from more than 200 distinct jurisdictions across our nine sample states, as well as several major textbook titles, digitally licensed curriculum products, and popular no-cost online resources.22

With instructional materials collected, we then appraised their content, focusing a standardized rubric on six topics: Native American History; the Founding Era; Westward Expansion; Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction; the Gilded Age and Progressive Era; and the Civil Rights Movement. Appraisals were not designed to celebrate or indict any individual teacher, district, curriculum developer, or state, but rather to discover meaningful patterns, which we present for each topic area in Part 4.

The Teacher

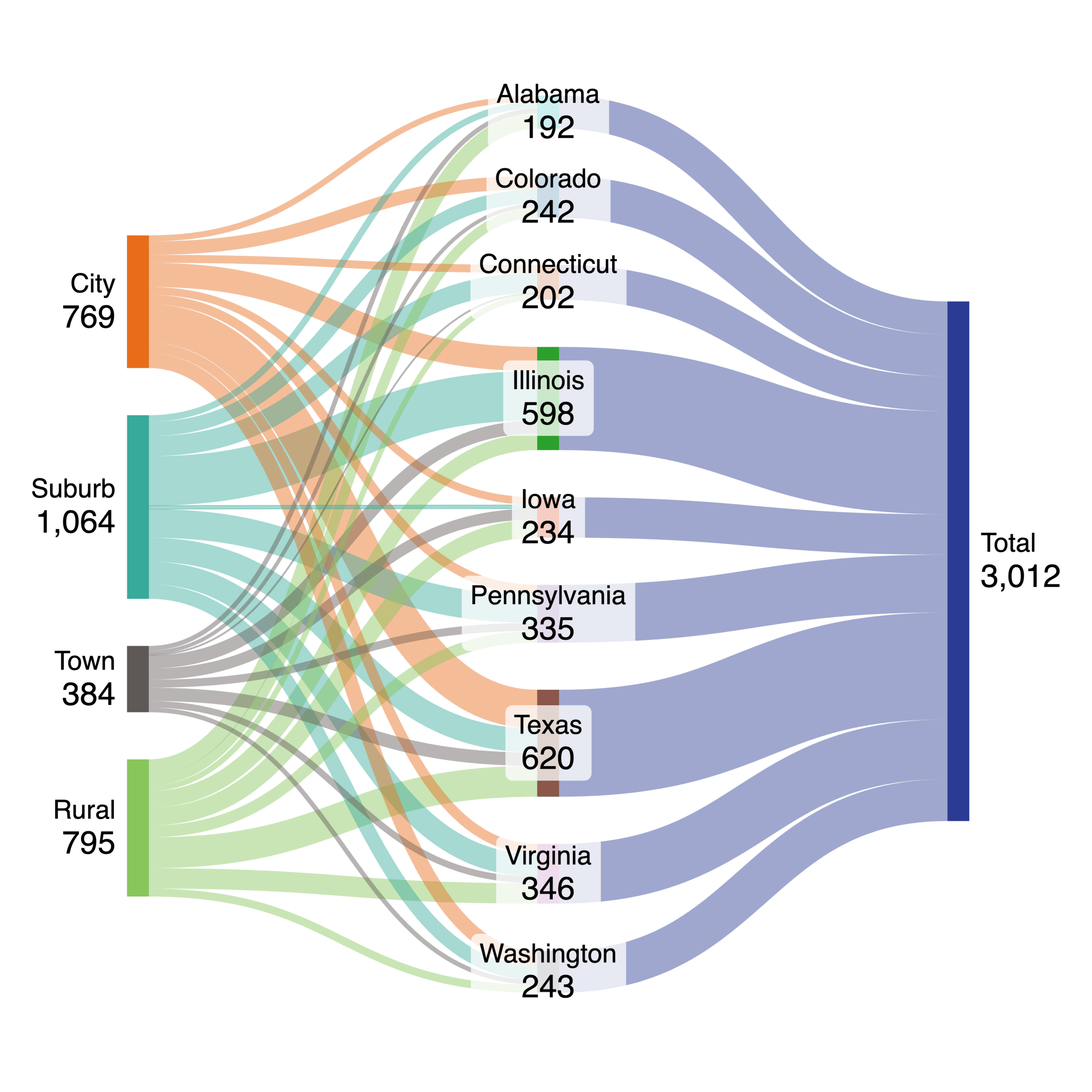

Ultimately, an accurate picture of what is taught, what is used, and what is valued can come only from teachers themselves. In April 2023, the AHA contracted with NORC at the University of Chicago to conduct a survey of public middle and high school US history teachers in the nine sample states. Together, the AHA, NORC, and University of Chicago Survey Lab teams developed the online instrument for the teacher survey.23 Designed to take about 30 minutes to complete, the survey elicited detailed information on a range of topics: teaching environment; background (years of teaching experience, highest academic degree); the role of curricular directives from the school, district, and state; materials used for teaching US history; familiarity with various free teaching resources; teaching goals and values; and what topics participants find most important, most rewarding, and most challenging to teach. To identify teachers to contact for the survey, NORC leased a directory of teachers from MDR Education, a division of the commercial analytics company Dun and Bradstreet.24 These teachers were then contacted and screened for eligibility for the AHA survey.25 Between April and August 2023, our survey hit the field, ultimately collecting usable responses from 3,012 participants whose school settings represent a full spectrum of locale types (city, suburb, town, rural) and social environments (socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic composition) in each state (Fig. 3). The number of teachers returning the survey in either “complete” or “partial” form represented a 13 percent response rate.

Fig. 3: Survey Respondents by State and Locale Type (n=3,012) (Made at SankeyMATIC.com)

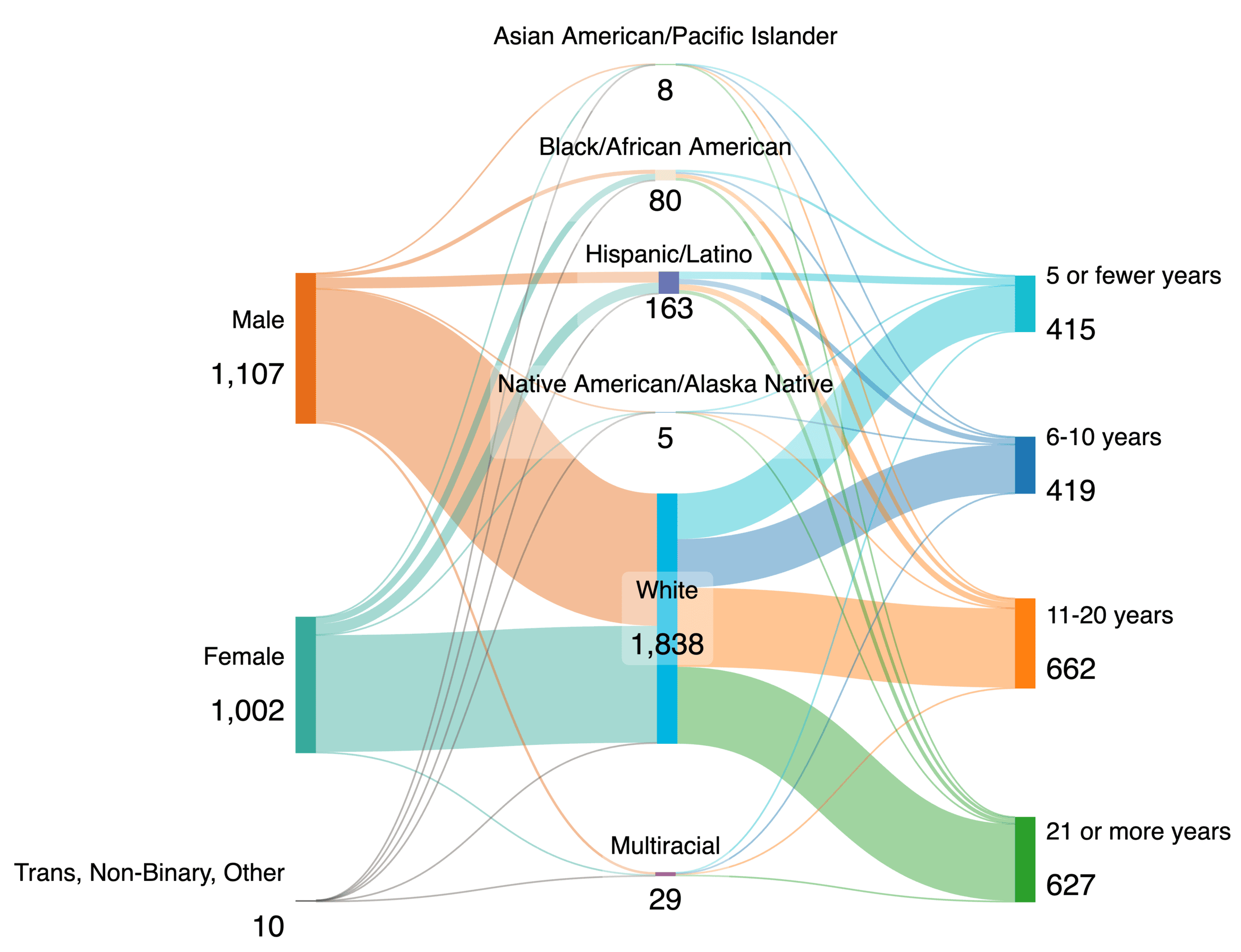

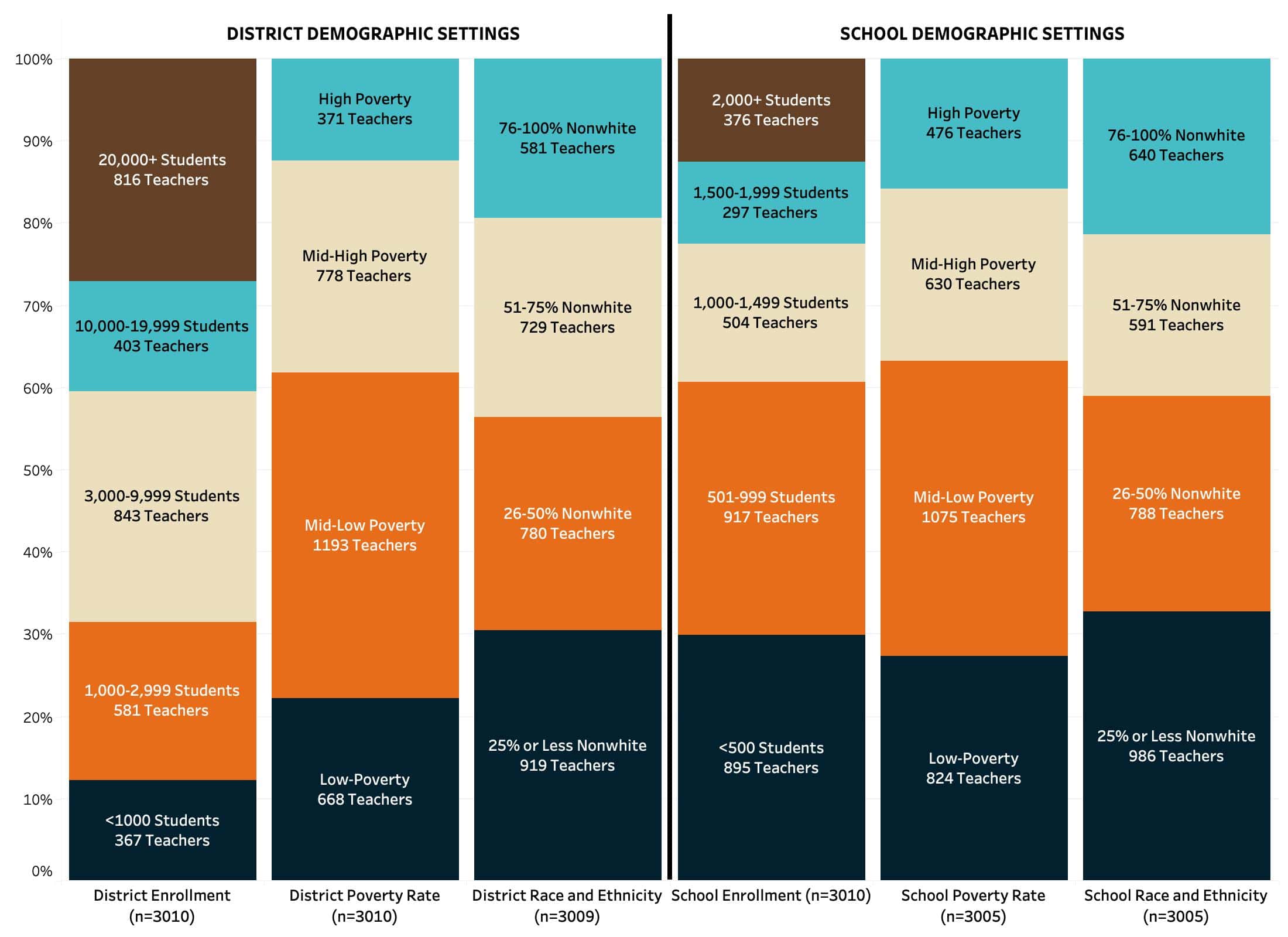

Survey results reveal how teachers conceptualize key topics in US history, the resources they trust, and the challenges they face. With anonymous responses sorted by state and district locale type, these data also allow us to interpret how diverse state and local environments of assessment, accountability, and standards affect US history teachers’ priorities and practices. Additional social and demographic information about each respondent (gender, race and ethnicity, years of teaching experience) and their school setting (socioeconomic profile, racial and ethnic composition) afford angles of additional analysis (Figs. 4 and 5).26

Fig. 4: Demographic Profile of Teacher Respondent Sample (sex, race/ethnicity, years teaching) (Made at SankeyMATIC.com)

Fig. 5: District and School Demographic Settings for Survey Respondents27

Taken together, our archive of teacher interviews, survey responses, and instructional resources dives deeply into teacher practice, embracing not only the prescriptive guidelines produced at the direction of district administrators but the in-use materials that teachers make and deliver to their students, bringing us as close to the meal of classroom instruction as can be achieved in a study of this kind.

Historical Antecedents

Current clashes are hardly the first time that US history curriculum has become a proxy battlefield for ideological factions in a broader American culture war. With each round of debate, new teams of investigators have stepped in to survey the curriculum. These researchers typically promised an objective appraisal but rarely without a stake in the outcome.28 Tensions associated with public education in a democracy propel these cycles of strife and audit. Conflicts between democratic and administrative authority create the potential for friction, as traditions of devolved local governance confront the layers of credentialed professionals who do the work of educating students and managing the system. Educators tasked with innovation or reform are bound to collide with broadly held expectations among parents that what schools conserve and transmit should resemble what was passed on to them.29 In the context of public schooling arranged into subject matter content, there is the added tension among professionals, whose various claims to expertise (as educators, administrators, or scholars) come into competition.

From Amateurs to Professionals

History has always been more likely than other subjects to provoke disputes about national identity.30 If the common schools were, as Horace Mann put it, an “apprenticeship for self-government,” history took the role of head tutor.31 American history, a widely used mid-19th-century textbook explained, inspired the pupil with tales of “virtue, enterprise, generosity, and patriotism” and equipped “a person to fulfill those duties which, in a free government, he may be called to discharge.”32

By the time historians had marked off their professional jurisdiction as scholars and educators (expressed in the founding of the AHA in 1884), state legislatures were turning schooling into a compulsory fact of American childhood. While professional historians were pleased to see history safely ensconced within the expanding educational systems of the industrial age, their sense of history’s purpose had grown beyond inspiration and instruction for citizenship. Converted by their experience with German empiricism, historians like Herbert Baxter Adams reported that the history seminar had “evolved from a nursery of dogma to a laboratory of scientific truth.”33

Professional historians built those laboratories and defined those truths within a social and institutional milieu bounded by race, class, and gender. In addition to dignifying many of the racial and gender prejudices common to the men welcomed into the professoriate, academic training increased the social distance between historians and history teachers. Many academics doubted whether the nation’s schoolteachers, many of whom were women and clergymen, were capable of transmitting the discipline’s new insights to American classrooms. As educator-psychologist and eugenicist G. Stanley Hall announced in an 1880 essay collection for history instructors, “no subject so widely taught is, on the whole, taught so poorly.”34 In response, historians enthusiastically joined the cascade of special committees convened between the 1890s and the 1920s to bring order, continuity, and disciplinary integrity to elementary and secondary education and made the scholarly case for history’s place within it. Authoring the 1894 report for the so-called “History Ten” at Madison, Wisconsin, historian Albert Bushnell Hart stressed history’s scientific and philosophical dynamism. Far from the “mere lists of lifeless dates” presented in too many American classrooms, Hart declared history a “training of the mind,” combining “the advantages of a philosophical and a scientific subject.”35

The emphasis on history as mental training reappeared as historians convened subsequent committees (of seven in 1899, five in 1905, and eight in 1907), while also affirming its centrality to popular notions of preparation for citizenship. The especially influential AHA Committee of Seven (1899) cast the toolbox of “historical-mindedness”—cause and effect, relationship and analogy, extraction of information, systematization of fact, exertion of imagination, and argument through “well-chosen words”—as tantamount to scientific training for culture, character, and citizenship.36 The committee argued that political (rather than social, economic, or cultural) matters should form the core of a US history course. In the American setting, they explained, a history of parties, politics, and policy created a vivid index of the social and industrial rhythms of the population.37

Progressive Era Turf Wars

By the Committee of Seven’s own admission, its survey of 300 schoolmasters provided an unsatisfactory picture of current history conditions, but ensuing studies by other auditors indicated that the AHA’s own publications had gained a wide influence. The committee’s recommendations rapidly became understood as a default reference for why, how, and in what order history should be taught in the schools.38 But historians soon found themselves jockeying for position with other experts. As the social sciences matured within the academy, newly trained professionals sought to break history’s monopoly within mass schooling.39 Social scientists found some solidarity with the educational Progressives of the era, who, from a variety of philosophical perspectives, viewed “traditional” history and other aspects of extant curriculum as hidebound barriers to the uniquely modern task of “social education.”40 The historical profession also had dissenters within its ranks, as prominent scholars like Charles Beard and Carl Becker called the prevailing history program an “educational outrage” and endorsed its “radical reorganization.”41

These constituencies gathered their critiques into the three-part National Education Association (NEA) publication, Report on Social Studies (1913–16). In addition to naming the new multidisciplinary umbrella under which history, geography, civics, and economics would be classified, the sociologist-heavy committee behind the report announced the goal of education as that of “social efficiency,” fusing Deweyan notions of meeting children’s “immediate needs” with managerial ambitions for the “neighborliness” of the social whole.42 Over the next several years, social studies’ innovations were further amplified by the NEA’s Cardinal Principles report on secondary education in 1918, the founding of the NCSS in 1921, and the proliferation of education professor Harold Rugg’s textbook series, Man and His Changing Society, during the 1920s and 1930s. Historians found themselves torn between asserting the primacy of history against social studies or elbowing for space within it.43

The AHA’s stewardship of a multiyear, Carnegie Foundation–funded interdisciplinary study of the nation’s schools further exposed the tensions among those seeking to shape social studies education. As the study’s component publications were released amid the economic crisis of the early 1930s, the emphasis, especially by educationist George Counts, on social studies education as a project of “social reconstruction” proved too much for some contributors.44 Prominent members of the study commission refused to endorse its final recommendations, and the popular press panned the study as radical propaganda. Ultimately, the AHA issued no statement of its own on the report, and by the 1940s, professional historians were making a steady retreat from the K–12 scene.45

History’s Persistent Public Profile

Despite an apparently diminishing profile for history in the schools, popular expectations—that history should be taught, and that its main themes should be heroism, patriotism, and (a contested) pluralism—drove an entire genre of activism. These popular expectations proved at odds with the social reconstructionism of the educationists and the self-declared intellectual dispassion of academic historians.46 Whatever the ambitions of social studies advocates, US history never left the curriculum, and Americans continued to care deeply about the moral lessons of its content.47 Many of those in charge of mass schooling continued to define history’s function as a project of nationalism and civilization, with special urgency to assimilate and develop the allegedly underdeveloped self-governing capacities of African Americans, Native Americans, and immigrants.48 For their part, European immigrants in the 1920s demanded that coverage of defining episodes of the American character, especially the revolution, be made inclusive of heroic contributions by their co-ethnics.49 In the Jim Crow South, Confederate nostalgists developed “measuring rods” to judge alleged Northern bias in textbooks, sought to censor interpretations with which they disagreed, and injected skewed interpretations that favored Southern white elites, exerting a durable influence on curricular treatments of slavery nationwide.50 Meanwhile, among networks of Black educators, a set of opposite motives sustained an ongoing series of debates and campaigns aimed at resisting and revising the pervasive omissions and denigrations of Black humanity found in most American history curricula, reified in works of popular history and cinema, and reiterated by some of the most distinguished historians in the academy. William Archibald Dunning, who served as AHA president in 1913, and his students promoted interpretations of post–Civil War Reconstruction that provided intellectual justification for racism and the exclusion of southern Blacks from political participation. Historical scholarship of this era thus added scholarly and cultural cachet to the racist portrayals that structured generations of American textbooks, popular histories, and film.51

By the 1930s, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, led by historian Carter G. Woodson, had succeeded in empowering Black educators to refute these expert judgments on their citizenship and dignity, reject racist textbooks, and replace them with a burgeoning crop of history curricula chronicling and celebrating the achievements of Black people—materials which, so long as they were designated for Black pupils in segregated schools and avoided documenting white racism, would be approved by white school boards.52 In the North, where the educational color line was more likely to be perforated, teachers and administrators like Madeline Morgan created curricula with an emphasis on contributions and uplift while also leveraging the sociological theories of race relations to promote teaching Black history to all public school students as part of World War II–era “intercultural education.”53

Social studies endured multiple rounds of direct criticism during the late 1930s and 1940s. Rugg’s textbooks came under concentrated attack from organized conservative activists, who characterized the books as a bundle of “collectivist theory” and New Deal propaganda, and ultimately achieved their removal from some districts.54 Meanwhile, wartime fueled concerns that social studies was being used, as historian Allen Nevins worried, “to slight, evade, and mangle the study of American History,” sapping Americans of their unity of national spirit.55 The New York Times amplified these fears in a series of reports, claiming to show an absence of US history in typical K–12 courses of study and a “striking ignorance” of US history among college freshmen.56 In a two-year Rockefeller Foundation–funded study, published in 1944, the AHA demonstrated that social studies had not in fact killed US history, which they found to be a nearly universal requirement in elementary and high school that was in fact receiving increased attention. The report’s authors struck a conciliatory tone regarding social studies, which they admitted had “caused some uneasiness” among historians. Social studies, they clarified, was a field of instruction or “federation of subjects” (just like mathematics or science)—neither a socialistic project nor antithetical to history.57

From Cold War to Culture War

While the subject of social studies had been securely installed in American curricula, the national security scripts of the Cold War supplied critics with renewed rationale for purging the field of its social reconstructionist roots and its assumed softness as a nondiscipline. While local anticommunists ran vigilance campaigns against allegedly “un-American” textbooks, popular authors bashed the bland fusion of progressive education with life adjustment classes, lumping social studies into the mix.58 The National Defense Education Act of 1958 may have been aloof to social studies, but its federally funded effort to sharpen America’s intellectual edge against the Soviets ushered in a wave of curricular reform, including the “New Social Studies” developed at the turn of the 1960s. Promising to engage teachers and students in “inquiry projects” that mirrored the disciplinary structures and scholarly methods in history and the social sciences, the New Social Studies ultimately proved difficult and expensive to implement.59 Successful mobilizations by religious conservatives against the anthropology-themed Man: A Course of Study (MACOS) curriculum in the early 1970s forced an end to federal funding for curricular experimentation in social studies.60 More influential and enduring was the growth of College Board’s Advanced Placement (AP) program, organized along the lines of traditional subject areas and a marker of high-status schools and districts throughout the late 20th century.61 With materials and testing created by College Board and the Educational Testing Service (ETS), and presumably aligned with introductory college courses, the AP program became a unique example of a nationally pervasive, if also exclusive, US history curriculum.62

As the social upheavals of the late 1960s wound their way into the schoolhouse, journalists and liberal policy scholars declared a rolling crisis in urban education. This sent educators scrambling to reinvent curricula to reach the “culturally deprived” and confront the social change that swirled around them.63 New countercultural subdisciplines and epistemological interventions launched by campus protests—such as ethnic studies, Black studies, and Chicano studies—promised precisely the curricular relevance sought by urban educators.64 Even as urban liberal coalitions ruptured over K–12 initiatives that emphasized Black consciousness and community control, some within the social studies coalition identified strongly with the insurgent themes of the moment.65 Institutional voices at the NEA, the NCSS, and new faculty cohorts in teachers’ colleges borrowed the critiques and vocabulary of Black Power, assigned critical pedagogy texts, formed antiracism and social justice committees, and published annual compendia of scholarship and teaching guides for ethnic studies.66 By the mid-1970s, the new disciplines had built a home on some university campuses, but political energies had clearly shifted to conservatives, inducing many ethnic studies proponents to mute the more critical notes of their interventions in favor of a more palatable “multiculturalism.”67

For conservatives, multiculturalism was but one example of the damage that post-1960s liberalism had done to public schools and universities. In the era of Ronald Reagan, policymakers hitched these cultural critiques to the longer-running movement among international groups like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to establish standard international metrics for educational progress.68 Taking wide aim at the softening of rigor and a fracturing of common experience they saw across the American curriculum, the authors of the influential 1983 publication A Nation at Risk notably refused to mention social studies, preferring traditional subject labels like history, geography, and economics.69Harnessing A Nation at Risk’s high-profile portrayal of mediocrity, educational historian Diane Ravitch and policy analyst Chester Finn Jr. built networks and arguments that fused a modernizing agenda for “outcome standards” in history with a call for reviving the humanities core.70 For Ravitch and Finn, the rise of a “skill training” approach in social studies and language arts (in contrast to history and literature) had allowed educators and policymakers to hide from the central question that any good humanities curriculum needed to answer: What was worth knowing? Finn and Ravitch indicted the educational establishment for a “tragic downward spiral that can only erode the culture, trivialize the intellect, and in time pauperize our civic life.”71 But they also appealed to a broad common sense among history teachers and the general public: concepts could not be learned free of facts; a common culture required common knowledge.

The Age of Accountability

By the early 1990s, aspects of the traditionalist critique had spread beyond the conservative base that had sparked the movement, as prominent historians like those writing for the Bradley Commission on History in the Schools echoed the disenchantment with the “do-your-own-thing formlessness of social studies,” blaming both early 20th-century Progressives and the science fair–style inquiry of the 1960s and 1970s.72 Meanwhile, on the college campus, the question of what was worth knowing was more contentious than ever, as multiculturalists sparred with traditionalists over the content of liberal education itself.73

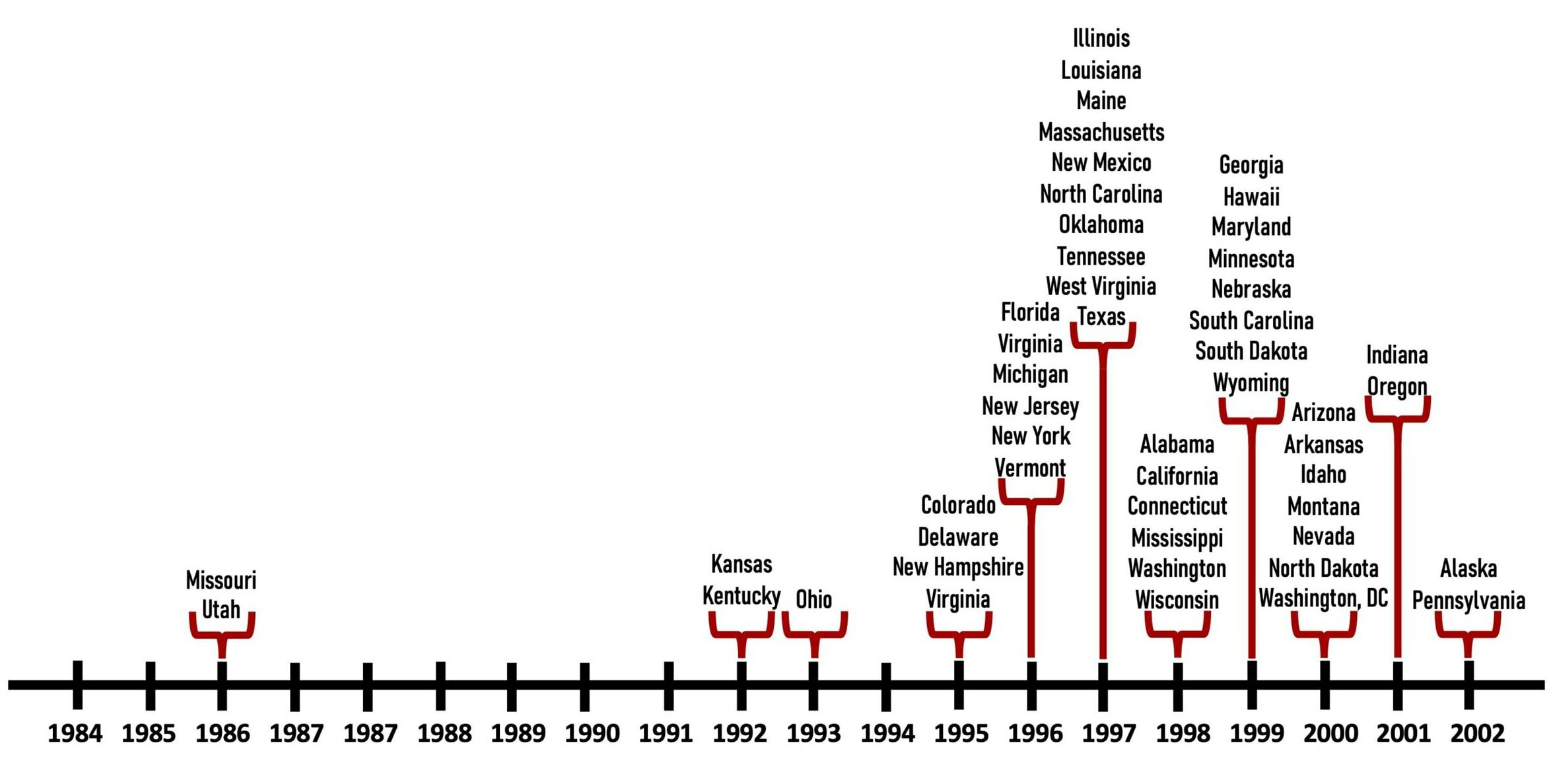

In contrast to campus and canon, K–12 education policy was increasingly becoming a zone of consensus for liberals and conservatives. The growth of the education state—at both the state and federal level—had occurred under both Democratic and Republican leadership.74 Under the bipartisan movement eventually known as accountability, education policymakers urged managerial competence over teacher labor, higher academic standards in clearly defined subject areas, and regular rounds of standardized assessment.75 As presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton announced federal education initiatives, the work of developing academic standards for history and social studies would take place at the state level but with substantial input and assistance from the national networks of expertise built by social studies educators and education agency administrators since the 1960s. Beginning with a small trickle in the early 1990s, a wave of states adopted social studies standards in the middle of the decade, mounting to a flood at the turn of the century. By 2002, all but two states had a set of adopted standards for social studies, with US history earning a place in each (Fig. 6).76

Fig. 6: Timeline of Social Studies Standards Adoption by State, through 2002

The movement for content-rich state standards and subject-specific course requirements reaffirmed history’s distinct role in the curriculum. But partisan conservatism famously reasserted itself in 1994, when National Endowment for the Humanities director Lynne Cheney led a lethal high-profile attack against the National Standards for History initiative that her own agency had funded, condemning the product as insufficiently celebratory of American heroes and institutions.77

The lesson was clear: recommending which history should be taught was likely to put you at the center of a culture war. The most prolific and successful effort to change the subject came from cognitive psychologist Sam Wineburg. Summarizing a decade of research in 1999, Wineburg stressed that thinking like a historian was a deeply humanizing project; beyond “names, dates, and stories,” he argued, history’s chief contribution was teaching “the virtue of humility in the face of limits to our knowledge and the virtue of awe in the face of the expanse of human history.”78

The rise of standards effectively brought history back as the lead subject within the mix of social studies. Social studies was still the prevailing term, and the NCSS launched an ongoing effort to generate model standards aimed at a multidisciplinary civic competence—becoming durable and top-selling references used by local education agencies.79 But the codification of state graduation requirements gave a renewed prominence to history, especially American history, as a specified content area. New groups like the National Center for History in the Schools (founded in 1988), the National Council for History Education (1990), National History Day (founded in 1974 and moved to the nation’s capital in 1992), the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (founded in 1994), and the Stanford History Education Group (founded in 2002) drew private and public funding to feed a national culture of history teaching. Popular appetites for heritage and history appeared to be mounting as well.80 Blockbuster filmmaking during the 1980s and 1990s dwelled extensively in historical topics, landing in classroom VCRs and DVD players.81 Meanwhile, an ongoing academic job crisis sent professional historians off campus and into high-profile projects of community history, oral history, and official commemoration.82 Over the first decade of the 21st century, the US Department of Education’s Teaching American History grants program channeled nearly one billion dollars of federal funds to thousands of projects nationwide, drawing local education agencies, history nonprofits, university scholars, and history teachers into episodes of collaboration.83 Despite the technical earmarking of federal funding for “traditional” history, much of the curricular and professional development of the era delicately pushed schoolhouse history away from heritage and collective memory and toward more sophisticated disciplinary notions of history “as a way of knowing.”84 But as an emphasis on testable skills came to dominate the accountability initiatives of the early 21st century, these definitions could also conveniently be pitched as a series of “reading strategies.”85

Within the expanding ecosystem of think tanks, philanthropies, and educational nonprofits that grew in the accountability era, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation (led by Finn) assumed the mantle of auditor of the new state standards documents for US history. Five times over two decades, Fordham’s team assessed each state with a letter grade. From their first assessment, Fordham established a strong preference for detailed, content-rich standards, concluding in 1998 that most state standards left many students “shortchanged of their own and the nation’s heritage.”86 By 2021, Fordham’s reviewers still saw inadequacy across the board but gave Ds and Fs to fewer than half of the states.87

Social Studies Redux

Throughout the era of bipartisan harmony on accountability, fault lines rumbled beneath social studies education. Even as textbook publishers calibrated their products to align with the seemingly uncontroversial lists of content being assembled in state capitals, the circulation of books like historian Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980) and sociologist James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me (1995) fed a popular appetite for unsettling received narratives, regardless of whether those narratives were in fact being taught. While fields of Black studies and Africana studies secured their institutional standing within the academy, a strong commercial market in popular Black history kept a range of critical perspectives on US history alive and available to a broad public.88 Meanwhile, the inheritors and offshoots of multicultural education—reconceptualized in the mid-1990s as “culturally relevant pedagogy” and “culturally responsive pedagogy”—were achieving substantial influence in education colleges.89 The institutionalization of these concepts and approaches within educational research and teacher preparation would continue into the 21st century.90

The collapse of the 1994 National Standards for History effectively sidelined questions of historical content knowledge from the ongoing movement to define academic standards at the national level. In the ambitious national education initiatives of the 21st century—George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act (2002), Barack Obama’s Race to the Top grants (2009) and Every Student Succeeds Act (2015), and the National Governors Association’s Common Core initiative (2010)—history and social studies were largely left aside.91 With national discussions of history focused on skills, cultural fights over history content stayed local.92

With new money and new enthusiasm for standards coursing through networks of curriculum professionals and state agency administrators at the turn of the 2010s, proponents of interdisciplinary social studies found a chance to regain their footing. Beginning as a working group within the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) in 2010, an expanding coalition of state agency officials, social studies experts, nonprofits, and professional associations (including the AHA) developed new guidance for social studies standards. The C3 Framework published in 2013 by NCSS, articulated core competencies for each discipline (history, civics, geography, and economics) while braiding them together in an interdisciplinary “inquiry arc”—a model for classroom routines meant to apply to any social studies subject area. The C3 Framework struck a delicate balance: distinguishing social studies against the mission creep of English and language arts while also demonstrating its coherence with the literacy expectations of the Common Core; promoting social studies as training for “the arts and habits of civic life” while asserting its nonpartisan character; and keeping various factions and disciplines inside the broad social studies tent.93 With the C3 Framework’s emphasis on inquiry, its history section focused on the components of historical analysis, rather than the lists of content knowledge common to many state history standards.94 The authors drew on the various schema of historical thinking skills that had flourished since the 1990s, including those developed by the AHA.95 With content knowledge once again avoided, Finn and the traditionalists offered their dissent, but the C3 Framework’s authors and proponents carried the day.96 Benefitting from a strong support network among state and local social studies specialists and seed money from a Race to the Top grant in New York, the C3 Framework gradually became the new lingua franca of social studies curriculum development in the 2010s.97 By 2017, 23 states had incorporated C3 into either standards or frameworks.98

Across the first two decades of the 21st century, civics, rather than history, rose to prominence as the fulcrum for new social studies initiatives. Perennial declarations of the nation’s poor civic health drew fodder from periodic reports of dismal civics scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).99 Major historical conjunctures—including the military campaigns of the global War on Terror, the China shock to American industry, the financial crisis and economic recession of 2007–10, the information revolution brought on by social media and smartphones, and the unexpected success of antiestablishment political movements—rippled across survey data to reinforce experts’ diagnoses of civic sickness.100 Beginning in the mid-2010s, state legislators passed dozens of new civics requirements, including 19 states that now mandate that students be tested using the civics portion of the US naturalization test.101 By the late 2010s, civic education reformers had joined older characterizations of disengagement and apathy to fresh portrayals of a citizenry they viewed as polarized, unruly, and misinformed.102 For agency administrators and foundation grantmakers seeking a curricular response, civics and citizenship education provided a ready-made reply, seeding a dense crop of new nonprofits and nonpartisan coalitions including iCivics (2009) and the Civics Renewal Network (2013).103 Educating for American Democracy (2019), notably included historians among its leadership and has framed its effort to integrate civics and history as an urgent crosspartisan project.

Conflicts over the last five years signal a potential reheating of the last generation’s culture wars over US history, and ambitious players have attempted to shape both the revision of academic standards and the development of curriculum.104 The 2014 revisions to the College Board’s curriculum framework for AP US History afforded a brief national platform for cultural and pedagogical conservatives to condemn what they saw as a replacement of traditional content with the “vagaries of identity-group conflict” and “abstract and impersonal forces.”105 Distinctive in years since 2016 has been the reduced salience of the accountability arguments that so dominated discussions between the 1990s and the 2010s. Widespread disenchantment with assessment regimes has deprived both political factions of constituencies with enthusiasm for talk of 21st-century career skills or the like.106 Recent proponents of curricular reform tend instead to make their arguments on the basis of moral reckonings over justice, equity, liberty, or patriotism.

Still, it is telling that flashpoints for debate in the early 2020s in Texas, South Dakota, and Virginia were occasioned by cycles of state standards revisions. Meanwhile, competing camps have released documents that seek to translate their ideological commitments into “standards” documents of their own, illustrating the enduring structures that the accountability movement has built around civic debate.107

← Introduction Part 2: National Patterns →

Notes

- See, for example, Jeremy Adelman, et al., “Trump 101,” Chronicle of Higher Education, June 19, 2016, https://www.chronicle.com/article/trump-101/; N. D. B. Connolly and Keisha Blain, “Trump Syllabus 2.0: An Introduction to the Currents of American Culture That Led to “Trumpism,” Public Books, June 28, 2016, https://www.publicbooks.org/trump-syllabus-2-0/. [↩]

- “‘We Are Committing Educational Malpractice’: Why Slavery Is Mistaught—and Worse—in American Schools,” New York Times Magazine, August 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/slavery-american-schools.html. [↩]

- “The New York Times Presents The #1619Project,” livestreamed on Aug 13, 2019, YouTube video, 2:11:46, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XrfV7w3EyGI. Meanwhile, the Times partnered with the Pulitzer Center to develop and distribute a free curriculum that would ensure young people would “be the ones to move it forward.” (Quote is from editor Jake Silverstein.) [↩]

- See, for example, Newt Gingrich, “Did Slavery Really Define America for All Time?” Newsweek, August 27, 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/newt-gingirch-1619-project-slavery-america-1456307; David Marcus, “US History Doesn’t Need to Be ‘Reframed’ Around Identity Politics; It Already Has Been,” The Federalist, August 20, 2019, https://thefederalist.com/2019/08/20/u-s-history-doesnt-need-reframed-around-identity-politics-already/. [↩]

- Donald J. Trump, “Inaugural Address” (speech, Washington, DC, January 20, 2017), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-14. [↩]

- Donald J. Trump, “Remarks by President Trump at South Dakota’s 2020 Mount Rushmore Fireworks Celebration” (speech, South Dakota, July 4, 2020), National Archives, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-south-dakotas-2020-mount-rushmore-fireworks-celebration-keystone-south-dakota/. [↩]

- Donald J. Trump, “Remarks by President Trump at the White House Conference on American History” (speech, Washington, DC, September 17, 2020), National Archives, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-white-house-conference-american-history/; Jonathan Butcher and Mike Gonzalez, “Critical Race Theory, the New Intolerance, and Its Grip on America,” Heritage Foundation, December 7, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/civil-rights/report/critical-race-theory-the-new-intolerance-and-its-grip-america; Manhattan Institute, “Woke Schooling: A Toolkit for Concerned Parents,” June 17, 2021, https://www.manhattan-institute.org/woke-schooling-toolkit-for-concerned-parents. For the AHA’s criticism and commentary on these initiatives, see “AHA Statement Condemning Report of Advisory 1776 Commission,” January 20, 2021, https://www.historians.org/news/aha-statement-condemning-report-of-advisory-1776-commission/; James Grossman, “On the Way Out, Trump Trashes History: Why the 1776 Report Is So Damaging,” New York Daily News, January 21, 2021, http://www.nydailynews.com/2021/01/20/on-the-way-out-trump-trashes-history-why-the-1776-project-is-so-damaging/. [↩]

- Christopher Rufo, “How Critical Race Theory Is Dividing America,” interview by Michelle Cordero, Heritage Foundation, October 26, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/progressivism/commentary/how-critical-race-theory-dividing-america. [↩]

- Jeremy C. Young and Jonathan Friedman, “America’s Censored Classrooms,” PEN America, August 17, 2022, https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms/. Legislatures passed quite a few “educational gag orders” in 2023, but most were directed to higher education or at LGTBQ+ content in K–12 health education. For more on educational gag orders, see PEN America’s database: https://pen.org/issue/educational-censorship/. [↩]

- Scholars have, without appeal to culinary cliche, explored this dynamic across a range of fields. For differences between “intended curriculum,” “enacted curriculum,” “learned curriculum,” and “assessed curriculum,” see Curtis C. McKnight, F. Joe Crosswhite, John A. Dossey, Edward Kifer, Jane O. Swafford, Kenneth J. Travers, and Thomas J. Cooney, The Underachieving Curriculum: Assessing US Schools: Mathematics from an International Perspective (Champaign, IL: Stipes, 1987); Andrew C. Porter and John Smithson, “Are Content Standards Being Implemented in the Classroom? A Methodology and Some Tentative Answers,” in Susan H. Fuhrman, ed., From the Capitol to the Classroom: Standards-Based Reform in the States (Chicago: National Society for the Study of Education, 2001). For “rhetorical curriculum” versus “formal curriculum” versus “curriculum-in-use,” see David Labaree, “The Chronic Failure of Curriculum Reform,” EdWeek, May 19, 1999, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-the-chronic-failure-of-curriculum-reform/1999/05. [↩]

- For the classic descriptions, see Karl E. Weick, “Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems,” Administrative Science Quarterly 21, no. 1 (March 1976): 1–19; John W. Meyer and Brian Rowan, “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony,” American Journal of Sociology 83, no. 2 (September 1977): 340–63. For helpful skepticism about loose coupling and an updated typology for understanding both the “institutional environment” and the “technical core,” see James P. Spillane and Patricia Burch, “Policy, Administration and Instructional Practice: ‘Loose Coupling’ Revisited” in The New Institutionalism in Education, Heinz-Dieter Meyer and Brian Rowan, eds. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006), 87–102. For arguments that analytic distinctions—between policy and practice, formation and implementation—clarify very little in the sociocultural web that enacts curriculum, see Edmund T. Hamann and Lisa Rosen, “What Makes the Anthropology of Educational Policy Implementation ‘Anthropological’?” in A Companion to the Anthropology of Education, Bradley A. U. Levinson and Mica Pollock, eds. (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 461–77; For recent confirmations of the old thesis, see Julia H. Kaufman et al., “How Instructional Materials Are Used and Supported in U.S. K–12 Classrooms: Findings from the American Instructional Resources Survey,” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-1.html. [↩]

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Table 209.50. Percentage of public school teachers of grades 9 through 12, by field of main teaching assignment and selected demographic and educational characteristics: 2017–18,” https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_209.50.asp. [↩]

- See Bessie Louise Pierce, Public Opinion and the Teaching of History in the United States (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926); Diane Ravitch and Chester E. Finn Jr., What Do Our 17-Year-Olds Know? A Report on the First National Assessment of History and Literature (New York: Harper & Row, 1988); Frances FitzGerald, America Revised: History Schoolbooks in the Twentieth Century (New York: Vintage, 1980); Kyle Ward, History in the Making: An Absorbing Look at How American History Has Changed in the Telling over the Last 200 Years (New York: New Press, 2007); David Jenness, Making Sense of Social Studies: A Publication of the National Commission on Social Studies in the Schools [a joint project of the American Historical Association, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, National Council for the Social Studies, Organization of American Historians] (New York: Macmillan, 1990); Roy Rosenzweig and Peter Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000). [↩]

- Jeremy A. Stern et al., The State of State Standards for Civics and U.S. History (New York: Fordham Institute, 2021), https://fordhaminstitute.org/sites/default/files/publication/pdfs/20210623-state-state-standards-civics-and-us-history-20210.pdf. [↩]

- Sarah Drake Brown and John Patrick, History Education in the United States: A Survey of Teacher Certification and State-Based Standards and Assessments for Teachers and Students, sponsored by the AHA and the OAH, 2003. [↩]

- Caroline McClure and Joann Zadrozny, Social Studies and Geography Survey for Middle and High Schools (San Marcos, TX: Gilbert M. Grosvenor Center for Geographic Education at Texas State University, 2015); Joann Zadrozny, Social Studies and Geography Survey for Middle and High Schools (San Marcos, TX: Gilbert M. Grosvenor Center for Geographic Education at Texas State University, 2017); Joann Zadrozny, Social Studies Standards Report (San Marcos, TX: Gilbert M. Grosvenor Center for Geographic Education at Texas State University, 2022). [↩]

- “Social Studies Standards Map,” AIR, 2023, https://www.air.org/social-studies-standards-map; Courtney Gross and Kimberly Imel, “The State of K–12 Social Studies Education,” AIR, March 2024, https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/State-of-K-12-Social-Studies-Education-Report-March-2024.pdf. [↩]

- Melissa Kay Diliberti, Ashley Woo, and Julia H. Kaufman, “The Missing Infrastructure for Elementary (K–5) Social Studies Instruction: Findings from the 2022 American Instructional Resources Survey” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023). https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-17.html. On textbooks, see Dana Goldstein, “Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories,” New York Times, January 12, 2020; Donald Yacovone, Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity (New York: Pantheon, 2022). On civics, see Sarah Shapiro and Catherine Brown, “The State of Civics Education,” Center for American Progress (February 2018); David Randall, “Learning for Self-Government: A K–12 Civics Report Card,” Pioneer Institute and the National Association of Scholars, white paper (February 2022). On the colonial and founding era (and the New Deal), see David Randall, et al., Skewed History: Textbook Coverage of Early America and the New Deal (New York: National Association of Scholars, 2021). On slavery, see “Teaching Hard History: American Slavery,” Southern Poverty Law Center, 2022. On Native American history, see Sarah B. Shear, Ryan T. Knowles, Gregory J. Soden, and Antonio J. Castro, “Manifesting Destiny: Re/presentations of Indigenous Peoples in K–12 U.S. History Standards,” Theory and Research in Social Education 43, no. 1 (2015): 68–101. On the history of the Reconstruction era, see Ana Rosado, Gideon Cohn-Postar, and Mimi Eisen, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth about Reconstruction,” Zinn Education Project, 2022. On the Civil Rights Movement, see the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance Project, “Teaching the Movement: The State Standards We Deserve,” (March 2012) and “Teaching the Movement 2014: The State of Civil Rights Education in the United States,” (March 2014). On attitudes among teachers and the broader public regarding history, see Peter Burkholder and Dana Schaffer, History, the Past, and Public Culture: Results from a National Survey (Washington, DC: AHA, 2021); Stephen Hawkins, Dan Vallone, Paul Oshinski, Coco Xu, Calista Small, Daniel Yudkin, Fred Duong, Jordan Wylie, Research Fellow, Defusing the History Wars: Finding Common Ground in Teaching America’s National Story (New York: More in Common, 2022); Clare Howard and Dalton Savage, “ Voices from the Field: Understanding the Needs of History Educators,” (National Center for History Education, forthcoming). [↩]

- See Patrick McGuinn, No Child Left Behind and the Transformation of Federal Education Policy (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006); Paul Manna, School’s In: Federalism and the National Education Agenda (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2006); Gareth Davies, See Government Grow: Education Politics from Johnson to Reagan (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007); Kenneth K. Wong, “Federalism Revised: The Promise and Challenge of the No Child Left Behind Act,” Public Administration Review (December 2008): S175–85; Gail L. Sunderman, Ben Levin, and Roger Slee, “Evidence of the Impact of School Reform on Systems Governance and Educational Bureaucracies in the United States,” Review of Research in Education 34 (March 2010): 226–53. [↩]

- To assemble a corpus of 877 individual legislative acts passed between 1980 and 2022, AHA researchers used a variety of databases, including HeinOnline, LexisNexis, and digital state legislative archives. Our assembled database provides a broad sample of lawmaking aimed at social studies instruction. Its reach is extensive but not exhaustive, and its scope is limited to the activities of state legislatures (as opposed to the actions of state boards of education). [↩]

- Our picture of curricular standards and practices was supplemented by interviews with 205 social studies specialists, teachers, and curriculum experts across 182 jurisdictions. All interviewees signed an agreement that affirmed their consent, guaranteed that their identities would not be connected to any quoted material, and that interview notes would be kept by the AHA as confidential documents for 60 years before being transferred to the AHA archive (see Appendix 2). Interview citations reference the subjects’ occupation and state, but names and districts are never specified. [↩]

- Tens of thousands of pages of instructional content constitute the archive for this research. These materials were collected directly from individual teachers and school districts and downloaded from publicly available state and district websites. Our archive contains 194 unique “collections” of instructional material obtained from teachers or districts in our nine sample states. Many reflected the approach of a single teacher, some expressed the priorities of a course team at a single school, and others contained directives and resources for an entire district. Citations in this report distinguish provenance by referring to “teacher documents” and “district documents.” In three states, we also encountered what we referred to as “multidistrict” documents, resources developed by the state agency or a state agency partner that were then adopted or used in multiple districts in that state. Following the links and directives included in multiple district documents took us to a cluster of published materials, which we also appraised, including leading resources from C3 Teachers, Crash Course US History, the DBQ Project, Digital Inquiry Group (formerly Stanford History Education Group), and Newsela. We also collected and appraised content in leading middle and high school textbook products for US history. The books appraised were: James West Davidson, Michael B. Stoff, and Jennifer Bertolet, My World Interactive: American History (Boston: Pearson Education, 2019); Emma J. Lapansky-Werner, Peter B. Levy, Randy Roberts, and Alan Taylor, US History Interactive (Paramus, NJ: Savvas Learning Company, 2022); Diane Hart, History Alive! The United States Through Industrialism (Rancho Cordova, CA: Teachers Curriculum Institute, 2021); Diane Hart, History Alive! The United States Through Modern Times (Rancho Cordova, CA: Teachers Curriculum Institute, 2017); Fredrik Hiebert, Peggy Althoff, and Fritz Fischer, American Stories (Chicago: National Geographic Learning, 2019); Fredrik Hiebert, Peggy Althoff, and Fritz Fischer, America Through the Lens: U.S. History, 1877 to Present (Mason, OH: National Geographic Learning/Cengage, 2023); Joyce Appleby, Alan Brinkley, Albert S. Broussard, James M. McPherson, and Donald A. Ritchie, Discovering Our Past: A History of the United States (Columbus, OH: McGraw Hill Education, 2018); Daina Ramey Berry, Albert S. Broussard, Lorri Glover, James M. McPherson, and Donald A. Ritchie, United States History: Voices and Perspectives (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2023); and US History: Civil War to the Present: Teacher’s Guide (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018). [↩]

- AHA researchers took the lead on conceptual content and NORC advised on question wording, question ordering and branching, informed consent statements, and future contacting information capture. The Survey Lab programmed the survey into Qualtrics and incorporated multiple rounds of iterative feedback from the AHA and NORC teams into the final online survey. [↩]

- The target population for the survey was all public school teachers who taught US history to one or more classes in grades 6–12 in the sample states during the 2022–23 academic year. MDR identifies teachers’ subjects and grade levels taught through a variety of online data sources, assigning each a “job code.” Subjects taught are identified in “job code” fields and up to eight job codes are identified for each teacher. US history is included in the job codes, but it was clear that the numbers identified in each of the nine states and overall were substantially lower than what would be expected based on student enrollments, class sizes, average teaching loads, and average numbers of US history courses taken by students. To reduce the likelihood of undercoverage, NORC leased a directory of all public-school teachers in the nine states who had one or more job codes identifying a social studies, social science, or history teaching field. This yielded a directory of over 56,000 teachers. [↩]

- Eligibility was defined as (1) teaching one or more US history classes to students in grades 6–12 in the 2022–23 school year, and (2) one or more of those US history classes was not an AP or other college credit class. Under these assumptions, there would be about 24,054 eligible US history teachers for the survey in the MDR directory. [↩]

- For an extended discussion of how our sample of survey respondents was assembled and evaluated for representativity, see Appendix 3, especially Table A23. [↩]

- The National Center for Education Statistics defines public school and district poverty levels by what percentage of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL). Students’ FRPL eligibility in low-poverty schools and districts is 25.0 percent or less, mid-low poverty is 25.1 to 50.0 percent, mid-high poverty is 50.1 to 75.0 percent, and high-poverty is more than 75.0 percent. See National Center for Education Statistics, “Concentration of Public School Students Eligible for Free or Reduced-Price Lunch,” Condition of Education (US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, 2024), https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/clb. [↩]

- For historians’ various frustrations with public understanding of history, as well as their many interventions beyond the academy, see Ian Tyrrell, Historians in Public: The Practice of American History, 1890–1970 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005). [↩]

- Labaree, “The Chronic Failure of Curriculum Reform.” [↩]

- Issues of sex education or more critical approaches to US history may seem ready-made for these flashpoints, but even subjects like New Math can provide the spark. See Lisa Rosen, “Myth-Making and Moral Order in a Debate on Mathematics Education Policy,” in Policy as Practice: Toward a Comparative Sociocultural Analysis of Educational Policy, Margaret Sutton and Bradley A. Levinson, eds. (New York: Ablex Publishing, 2001); Christopher J. Phillips “The New Math and Midcentury American Politics,” Journal of American History 101, no. 2 (September 2014): 454–79. [↩]

- Horace Mann, Ninth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Board of Education, Boston, December 10, 1845 (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, State Printers, 1846), 37. [↩]

- Charles Goodrich, History of the United States of America (Boston: Hickling, Swan, and Brewer, 1857), 1. [↩]

- Adams, quoted in Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The Objectivity Question and the American Historical Profession (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 33. [↩]

- G. Stanley Hall, as quoted in David Warren Saxe, Social Studies in the Schools: A History of the Early Years (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), 32. [↩]

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Report of the Committee of Ten on Secondary School Studies, National Education Association (New York: American Book Company, 1894), 168. [↩]

- Andrew C. McLaughlin, Herbert B. Adams, George L. Fox, Albert Bushnell Hart, Charles H. Haskins, Lucy M. Salmon, and H. Morse Stephens, The Study of History in the Schools: A Report to the American Historical Association of the Committee of Seven (1898), 26. [↩]

- McLaughlin, et al., The Study of History in the Schools, 74–78. [↩]

- See E. W. Osgood, “The Development of Historical Study in the Secondary Schools of the United States,” School Review 22, no. 7 (1914): 444–54. [↩]

- Robert Orrill and Linn Shapiro, “From Bold Beginnings to an Uncertain Future: The Discipline of History and History Education,” American Historical Review 110, no. 3, (June 2005): 727–51, quotation 739. [↩]

- The “Progressives” were a mixed bunch, of course—“not a single entity but instead a cluster of overlapping and competing tendencies.” David F. Labaree, “Progressivism, Schools and Schools of Education: An American Romance,” Paedagogica Historica 41, nos. 1 and 2, (February 2005): 275–88. On the classic typology of “pedagogical Progressives” and “administrative Progressives,” see David Tyack, The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974). For an extended discussion of historiographic complications, see Herbert Kliebard, “The Search for Meaning in Progressive Education: Curriculum Conflict in the Context of Status Politics,” in The Struggle for the American Curriculum, 1893–1958 (New York: Routledge, 2004), 272–91. See also Ronald W. Evans, The Social Studies Wars: What Should We Teach the Children? (New York: Teachers College Press, 2004), 21–24. [↩]

- Beard, quoted in Saxe, Social Studies in the Schools, 135; Becker, quoted in Orrill and Shapiro, “From Bold Beginnings,” 740. [↩]

- Saxe, Social Studies in the Schools, 148–53. Quotes in Arthur William Dunn (compiler), Report of the Committee on Social Studies of the Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Education of the National Education Association: The Social Studies in Secondary Education (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1916), 9–10. The account presented here skates over several historiographic disputes. For a useful overviews, see Stephen Thornton, “A Concise Historiography of the Social Studies,” in The Wiley Handbook of Social Studies Research (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2017), 7–41; Thomas Fallace, “The Intellectual History of the Social Studies,” in The Wiley Handbook of Social Studies Research (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2017), 42–67. For more on the centrality of education to the Progressives’ broader social vision, see Lawrence A. Cremin, The Transformation of the School: Progressivism in American Education, 1876–1957 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969); Daniel Rodgers, Contested Truths: Keywords in American Politics since Independence (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987) 179–87; Leon Fink, Progressive Intellectuals and the Dilemmas of Democratic Commitment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997). [↩]

- Orrill and Shapiro, “From Bold Beginnings,” 746. [↩]

- Evans, The Social Studies Wars, 52–59; Herbert Kliebard, The Struggle for the American Curriculum, 1893–1958 (New York: Routledge, 2004), 162–67. [↩]

- Orrill and Shapiro, “From Bold Beginnings,” 747. [↩]

- A 1923 AHA resolution put things bluntly: “Attempts, however well meant, to foster national arrogance and boastfulness and indiscriminate worship of national ‘heroes’ can only tend to promote a harmful pseudo patriotism.” “Resolutions on History Teaching in the Schools,” AHA, December 29, 1923, https://www.historians.org/resource/resolutions-on-history-teaching-in-the-schools/. [↩]

- For elaboration of history’s hold on the curriculum through the 1930s, see Thomas Fallace, “Did the Social Studies Really Replace History in American Secondary Schools?” Teachers College Record, 110, no. 10 (October 2008): 2245–70. [↩]

- Thomas D. Fallace, “The Racial and Cultural Assumptions of the Early Social Studies Educators, 1901–1922,” in Histories of Social Studies and Race: 1865–2000, Christine Woyshner and Chara Haeussler Bohan, eds. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 37–55. Campbell F. Scribner, “The Dilemmas of Americanism: Civic Education in the United States” in The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education, Andrew Peterson, Garth Stahl, and Hannah Soong, eds. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 1–14. On Progressive era educators’ various contests over cultural assimilation, racial development, social stratification, and gender, see Julia Wrigley, Class Politics and Public Schools: Chicago, 1900–1950. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1982); William J. Reese, Power and the Promise of School Reform: Grass Roots Movements during the Progressive Era (New York: Teachers College Press, 1986); James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988); Michael B. Katz, Reconstructing American Education (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989); John L. Rury, Education and Women’s Work: Female Schooling and the Division of Labor in Urban America, 1870–1930 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991); David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995); Jacqueline Fear-Segal, White Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007); Cristina Viviana Groeger, The Education Trap: Schools and the Remaking of Inequality in Boston (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021). [↩]

- Jonathan Zimmerman, Whose America: Culture Wars in the Public Schools (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 12–28. [↩]

- In 1915, Mary Margaret Birge, chair of the textbook committee of the Texas Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, proclaimed: “Strict censorship is the thing that will bring the honest truth. That is what we are working for and that is what we are going to have.” Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Convention of the Texas Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy . . . 1915 (1916), 43, cited in Fred Arthur Bailey, “Charles W. Ramsdell: Reconstruction and the Affirmation of a Closed Society,” in The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction, John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery, eds. (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013), 251. On the grassroots movement to keep Confederate versions of history alive, see Mildred L. Rutherford, A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges, and Libraries (Athens: United Confederate Veterans, 1920); Herman Hattaway, ‘‘Clio’s Southern Soldiers: The United Confederate Veterans and History,’’ Louisiana History 12, no. 3 (Summer 1971): 213–42; Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865–1913 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987); Zimmerman, Whose America, 30–38. [↩]

- Dunning’s views, historian Eric Foner notes, “dominated historical writing and public consciousness for much of the twentieth century” and “did more than reflect prevailing prejudices—they strengthened and helped perpetuate them. They offered scholarly legitimacy to the disenfranchisement of southern blacks and to the Jim Crow system.” Eric Foner, “Preface,” in The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction, John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery, eds. (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013), xi. On the academy’s role in reflecting and ratifying Confederate apologia and racist portrayals of Black agency, see Novick, That Noble Dream, 72–80; David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2002); John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery, eds., The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013); Sarah Weicksel and James Grossman, “Racist Histories and the AHA,” Perspectives on History 59, no. 2 (February 2021), https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/racist-histories-and-the-aha-february-2021/. On the role of mass culture in amplifying Lost Cause mythology (especially in the work of D. W. Griffith and Claude Bowers), see Jack Temple Kirby, Media-Made Dixie: The South in the American Imagination (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986); David E. Kyvig, “History as Present Politics: Claude Bowers’ The Tragic Era,” Indiana Magazine of History 73, no. 1 (March 1977): 17–31; Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: A History of the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). [↩]

- See Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1933); August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, Black History and the Historical Profession, 1915–1980 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986); Jacqueline Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993); Wilson Jeremiah Moses, Afrotopia: The Roots of African American Popular History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Sarah Bair, “The Early Years of Negro History Week, 1926–1950,” in Histories of Social Studies and Race: 1865–2000, Christine Woyshner and Chara Haeussler Bohan, eds. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 57–77; Jarvis Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021); Zimmerman, Whose America, 38–49. For primary sources, see Imani Perry, Jarvis Givens, and Micha Broadnax, The Black Teacher Archive, https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/black-teacher-archive. [↩]

- Ian Rocksborough Smith, Black Public History in Chicago: Civil Rights Activism from World War II into the Cold War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018), 15–48; Michael Hines, A Worthy Piece of Work: The Untold Story of Madeline Morgan and the Fight for Black History in Schools (Boston: Beacon Press, 2022). [↩]

- Ronald W. Evans, This Happened in America: Harold Rugg and the Censure of the Social Studies (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2006); On the 1930s, see Christine K. Erickson, “‘We Want No Teachers Who Say There Are Two Sides to Every Question’: Conservative Women and Education in the 1930s,” History of Education Quarterly 46, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 487–502. On the 1940s, see Charles Dorn, “‘Treason in the Textbooks’: Reinterpreting the Harold Rugg Textbook Controversy in the Context of Wartime Schooling,” Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education 44, no. 4 (August 2008): 457–79; Zimmerman, Whose America, 50–73. [↩]

- Nevins, as quoted in Evans, The Social Studies Wars, 88. [↩]

- Evans, The Social Studies Wars, 84–92. [↩]

- “History among the Social Studies,” chapter 5 in The Report of the Committee on American History in Schools and Colleges of the American Historical Association, the Mississippi Valley Historical Association, and the National Council for the Social Studies (New York: Macmillan, 1944), https://www.historians.org/resource/chapter-5-history-among-the-social-studies/. [↩]

- Evans, The Social Studies Wars, 97–116. [↩]

- Evans, The Social Studies Wars, 122–34. For an analysis of the New Social Studies’ delicate fusion of student-centered, scientistic, and anticommunist impulses, see Campbell F. Scribner, “‘Make Your Voice Heard’: Communism in the High School Curriculum, 1958–1968,” History of Education Quarterly 52, no. 3 (August 2012): 351–69. [↩]

- For a first-hand account, see Peter Dow, Schoolhouse Politics: Lessons from the Sputnik Era (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991). For technological contexts, see Victoria Cain, Schools and Screens: A Watchful History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), chapters 2, 3, and 4. [↩]

- For a critical account of AP’s rise and growth, see Annie Abrams, Shortchanged: How Advanced Placement Cheats Students (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023). [↩]