What Are Students Learning about Our Nation’s History?

Since 2020, an expanding and contentious debate over history education has generated outrage, wild claims, and a growing sense of alarm in homes and communities across the country. State legislators, school board members, pundits, parents, and activists endorse a dizzying array of potential solutions even as few seem to agree on either the root cause or the nature of purported crises in our public schools.

These debates storm across a landscape of history education often mischaracterized through stereotypes and assumptions grounded in overtly ideological agendas. The loudest voices frequently focus on what they believe students learn in the classroom. Without reference to any concrete evidence that teachers routinely use a series of “inherently divisive concepts” or hot-button texts, state governments across the country have created unprecedented legal restrictions on the content of history instruction. At least 20 states have enacted legislation or taken executive action in this vein, while related controversy has spilled over into the revisions process for academic standards.1 Opponents of these prohibitions accuse legislators and their allies of invention and distortion in these caricatures of curriculum and practice.

This political theater and vigorous debate lack an important element: evidence drawn from careful research. While scholars and journalists issue periodic reviews of textbooks and state standards, no research team has developed a comprehensive analysis of the full picture—the what, how, and why of middle and high school US history instruction.

In 2022, the AHA launched the most comprehensive study of the national US history teaching landscape undertaken in the 21st century. We wanted to know what is actually happening in classrooms across the country. Are teachers distorting history or indoctrinating children? Careful research transcends the heat and noise surrounding history instruction and enables us to provide a helpful and reliable source of information to parents, administrators, legislators, journalists, historians, and the many other stakeholders invested in the future of public education.

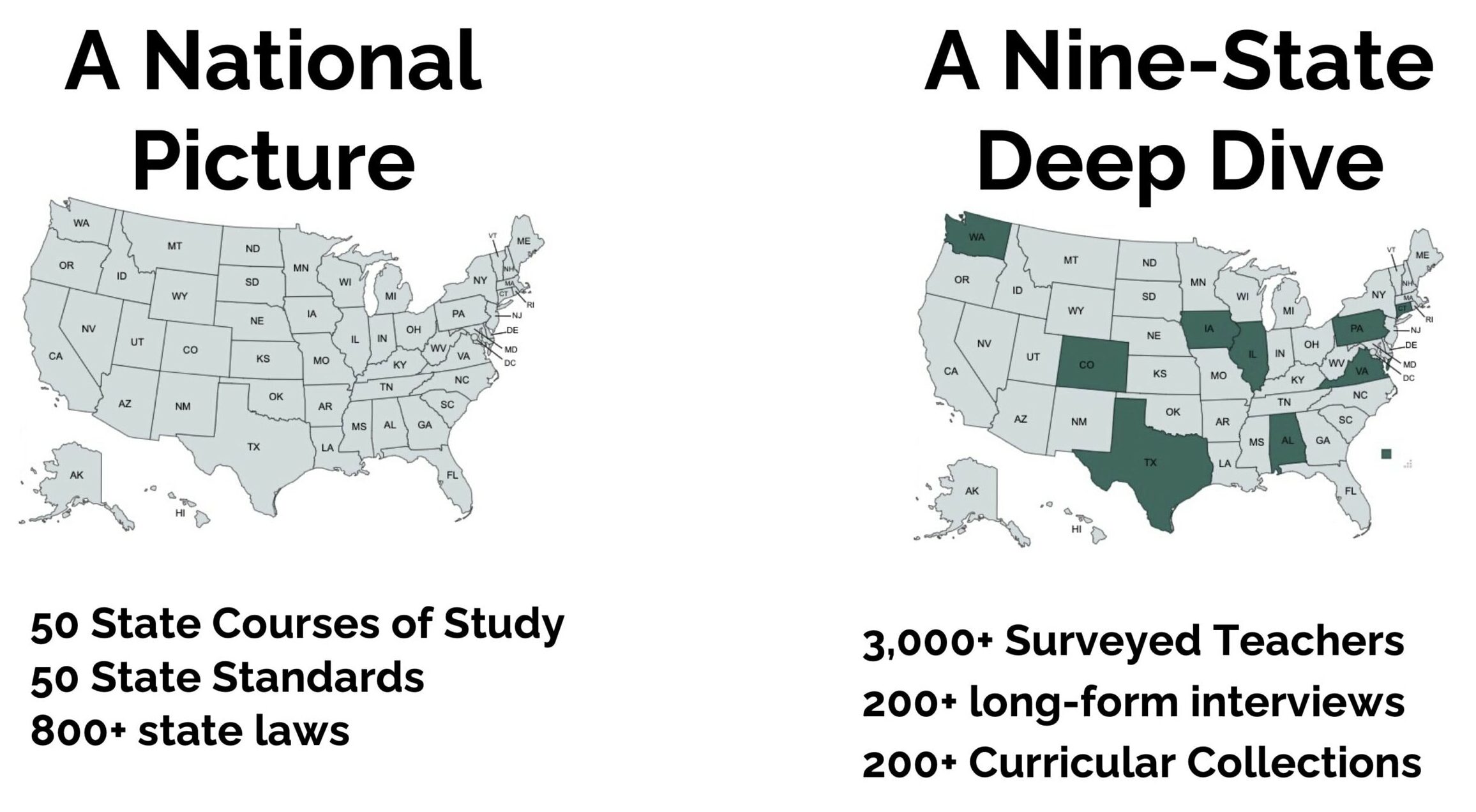

This report distills insights gathered during a two-year exploration of secondary US history education to illuminate the three levels where decisions are made about what students learn: the state, the district, and the teacher. Combining a 50-state appraisal of standards and legislation with a nine-state deep-dive into local contexts, we commissioned a NORC at the University of Chicago survey of over 3,000 middle and high school US history educators, conducted long-form interviews with over 200 teachers and administrators, and collected thousands of pages of instructional materials from small towns to sprawling suburbs to big cities (Fig. 1). The US education system—diverse, devolved, and divided—could never be captured by the blunt slogans that have dominated partisan media and drawn attention from even more careful observers.

Fig. 1: Overview of Project Source Base

What have we learned?

First and foremost, we’ve learned that secondary school US history teachers are professionals who are concerned mostly with helping their students learn central elements of our nation’s history. Many teachers participate in a nationwide culture of history education that operates through channels rarely addressed in public debates on the topic. The lessons, assignments, and curricular materials we reviewed display broadly similar approaches to US history across states and localities. We did not find indoctrination, politicization, or deliberate classroom malpractice. A lack of resources, instructional time, and professional respect represent far clearer threats to the integrity of history education across the United States. If there is any wholly inaccurate message being sent by our schools to millions of students and their families, it is that history is not important enough to command time, attention, and public resources.

We have also learned that a compelling answer to the question of “what is actually taught in American history classrooms?” rests on an understanding of how decisions are made about what is taught, how teachers feel about the process, and, ultimately, what goes right and wrong with history along the way.

This story—of how (or whether) curricular initiatives travel from national priorities, through state agencies and local bureaucracies, across networked professional associations and interest groups, and onto the teacher’s desk—is not easily summarized. Borrowing a culinary metaphor, our study of standards and curricula is an appraisal of required menus and popular recipes, not a review of the meal itself.2 A vast array of cookbooks, ingredients, and health codes shape what the chef (the teacher) is enabled, encouraged, and obliged to incorporate as they step into the kitchen to prepare a meal (or to sit down on Sunday night to prepare a lesson). Consequential decision-making happens at every level, even if many state and district-level curricular cookbooks never leave the shelf.

We highlight several insights that we hope readers will consider as they contemplate the future of education:

1. Common Ground: While there is no national education system, an informal culture of history teaching grounded in common goals and a shared professional sensibility is evident nationwide in both discourse and classroom practice. The accountability movement in US education pulled social studies into successive rounds of standardization beginning in the 1990s. While history was left unevenly marked by the double-edged sword of standardized testing, accountability reinforced similar courses of study and shared sets of values, norms, resources, and vocabulary that teachers nationwide recognize. This common ground is sustained by professional organizations of teachers and administrators, curriculum publishers, social media groups, resource providers, and professional development programming.

The good news is that the US history typically taught in public schools is not riddled with distortions or omissions. Many teachers present variations on a broadly consistent outline of US history that is grounded in evidence, familiarity with foundational primary sources, and the work of professional historians as refracted through commonly used educational resources. Local curricula and state standards lay the groundwork for a generally unobjectionable (if limited) structure of coursework where rigorous history can certainly thrive. Curricula are at their best when questions of causation, context, and significance frame the content.

When materials fall short of the expectations of professional historians, it is typically because history instruction has been streamlined to focus on bare facts, banal platitudes, flat inevitabilities, or a vague set of literacy skills rather than meaningful knowledge. State mandates and prohibitions are unlikely to solve this problem; social studies teachers need more classroom time and more professional development.

2. Cold Fronts and Hot Spots in the Culture War: Media accounts of a politically charged war for the soul of the social studies are overblown. The national teaching culture described above varies from state to state, district to district. But generally it is grounded in professional norms and shared commitments that bear little resemblance to caricatures of classroom indoctrination. Yes, politics does intrude and perhaps sometimes distort. Teachers in some locales have been bullied and spooked away from perfectly good lessons by threats associated with right-wing ideological activists and punitive state legislation. Meanwhile, teachers in some progressive enclaves cringe as administrators insist on ideologically inflected initiatives that push history and historical analysis to the margins. Still, the significant majority of teachers do not face regular political objections to the way they teach US history; far from fending off throngs of critics, many struggle to get parents, students, and even administrators to care about history at all.

The teachers in our sample consistently express a strong and praiseworthy professional commitment to partisan neutrality in the classroom. Teachers want students to read and understand founding documents to prepare them for informed civic engagement. They also want them to grapple with the complex history and legacies of racism and slavery. Curricular materials associated with overtly partisan or ideological messaging can expect a cool reception from teachers.

History is always political.3 At a minimum, historians and educators make decisions about what people, texts, events, and topics are worth knowing and understanding. But the politics of historical interpretation rarely align precisely with any single political party or movement. A majority of history educators embrace an approach to the past that is grounded in helping students recognize the importance of respectful attention to multiple perspectives, even those with which they may vigorously disagree. Americans will continue to debate what is worth learning about their nation’s history—and they won’t always agree.

3. Free Online Resources Outweigh Textbooks: Educational publishing is still big business, but traditional textbooks are unlikely to stand at the center of history instruction. The eclipse of textbooks reflects the advent of digital learning management systems (LMS), the proliferation of online teaching materials and open educational resources (OER), a relentless push for “one-to-one” ratios of computing devices to students, and a student population that many teachers increasingly view as unprepared and/or unwilling to read critically or at length. In place of or as a supplement to textbooks, schools license digital materials on an ongoing basis, often outside of state instructional materials adoption processes or district approval procedures. Meanwhile, teachers make prolific use of a decentralized universe of no-cost or low-cost online resources. US history teachers rely on a short list of trusted sites led by federal institutions including the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and Smithsonian museums.

4. Testing Matters, for Better or for Worse: The presence of a state-mandated assessment in history exerts a strong influence on district conditions, with local ramifications for staffing, reporting, interim testing, and curricular alignment. Teachers in states with and without testing report mixed feelings in each case, sensing the boost in clarity, status, and resources that tested subjects receive while bemoaning the narrowing of curriculum that can accompany standardized assessment. Testing at the state level tends to produce more testing and administrative paperwork at the local level. Generally, however, trends appear to be moving away from standardized testing in social studies. History was always a collateral target of the accountability movement, and assessment rituals have been slow to reassert themselves following the interruption of the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Teachers Make Curricular Decisions: Despite efforts by state agencies, district administrators, and school principals to align, synchronize, assess, and discipline instruction, teachers have substantial discretion in deciding what they teach, how they teach it, and what materials they use. Outside of assessment states, very few teachers perceive that their district requires anything of them beyond the pace of the course. At the course-team level, however, collaboration is indeed ascendant, whether chosen freely or mandated by district or school administrators. Looking across their careers, veteran teachers report a clear trend away from autonomy and idiosyncrasy and toward alignment and common assessment. Nevertheless, many teachers retain considerable control over crucial decisions about what they say and do in their classrooms.

6. Bad Questions Give Inquiry a Bad Name: One of the most promising developments of the past 40 years of history instruction has been the increased focus on history as a discipline-specific process of inquiry. Teachers have more sophisticated curricular resources than ever to help students inquire, think, read, and argue like historians. However, there may be collateral costs to this otherwise productive focus on inquiry. When content (names, dates, places, stories) are blurred in favor of skills-based abstractions, teachers may have more difficulty defending the integrity of history against politicized accusations that what they’re teaching is nothing more than a “biased,” “divisive,” or “problematic” opinion. Nor does calling something an inquiry guarantee that moralism, presentism, or fatalism won’t creep into history teaching. Ongoing dialogue among academic historians, teachers, administrators, curriculum developers, and the public can sharpen collective understandings of the difference between good historical questions and the questions that history can’t answer.

7. Calls for Help: Teachers freely admit where they could use more support, citing areas of challenge on both ends of the American history timeline; precolonial Native America and events since the 1970s rank highly as areas for which teachers voice the need for more training. Judging from the curricula we appraised, historians across all subjects and eras of US history have an important opportunity to distill and communicate recent insights from their subfields to K–12 educators. Moreover, K–12 educators have a crucial opportunity to inform the type of research, writing, and professional development (PD) that would be most productive.

Whether under pressure to rush through a topic, or admitting that they lack strong content knowledge in particular areas, teachers cite the need for ongoing, history-rich professional development. This is particularly urgent, as district-organized PD tends to focus on technology or pedagogy, rather than the subject-area enrichment that teachers say they want.

This report documents and analyzes the AHA’s exploration of the content and contours of US history lessons across the country. To fully contextualize what teachers deliver in the classroom, we examine the complex balance between state policy, district-level curricula, and the work of individual teachers. Classroom educators have much more autonomy and exercise a far greater degree of professional engagement than many legislators and activists recognize. Where teachers turn for educational resources and the extent to which they consult state academic standards can matter more than the content of textbooks, the arcana of administrative guidelines, or the political party for which they cast a ballot.

Organization of the Report

This report is driven by three questions:

- What are American middle and secondary school students taught about US history?

- Who decides what will be taught in US history?

- What sources, texts, and materials do teachers actually use when they teach US history?

We address these questions across the four parts of the report.

Part 1: Contexts explains the rationale and methodology for the study, including the reasons we chose particular research questions, sample sites, and source bases. We show how we captured a snapshot of conditions across three levels of curricular decision-making: the state, the district, and the teacher. This section places the report in historical context, offering a brief account of the perennial and evolving debates about history education in the United States.

Part 2: National Patterns highlights trends and anomalies in the patchwork of US history education across the United States, including courses of study and the scope (the temporal focus) of coverage. We explain the rise of state education agencies and state social studies standards along with common sources of alignment such as the College, Career, and Civic Life Framework for Social Studies State Standards (C3 Framework). We appraise the role of state-mandated assessments as well as the variable rationales, stakes, and implementation of history testing. We highlight national patterns of legislation related to history and civics education since 1980, including mandates for coverage of diverse groups and other topics, noting where legislation has changed or been consistent across the states.

Part 3: Curricular Decisions moves into the schoolhouse, discussing how teachers navigate their professional environments and responsibilities. We explore the tug-of-war between school administrators and history teachers, detailing the curricular effects of these labor dynamics on paperwork, pedagogy, and politics. We track the rise of teaching teams and their varying levels of alignment from common exams to pacing guides. While documenting the decline of textbooks in K–12 history classes, we explain what has replaced them, especially the range of free online sources and digitally licensed curricula. We describe the various forms these resources take and critically consider the implications of their emphasis on inquiry. This section concludes with a detailed exploration of the pressures that teachers face as they attempt to navigate controversy: partisan resources they try to avoid; ideological tensions stemming from state and district policy; and conflicts introduced by parents and community members.

Part 4: Curricular Content appraises specific content areas and how teachers and districts make plans to teach US history. Based on materials we collected from teachers and districts, we focused a standardized rubric on six topics, chosen for their widespread classroom coverage and their prominence in public, political, or historiographical debates: Native American History; the Founding Era; Westward Expansion; Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction; the Gilded Age and Progressive Era; and the Civil Rights Movement. In all cases, we intended our appraisals to be part of a constructive description of meaningful patterns, not a celebration or indictment of any individual teacher, district, curriculum developer, or state education agency.

Notes

- The count is higher still when it includes restrictions focused on elementary or postsecondary education. On legislative and executive initiatives, see Jeremy C. Young and Jonathan Friedman, “America’s Censored Classrooms 2023,” PEN America, November 9, 2023, https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2023/. On state standards, see Julia Brookins and Brendan Gillis, “Maintaining Standards: Recent AHA Contributions to the Fight for Honest History Education,” Perspectives on History 61, no. 5 (May 2023), https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/maintaining-standards-recent-aha-contributions-to-the-fight-for-honest-history-education-may-2023/. [↩]

- The metaphor is repeated often by educational historian Jonathan Zimmerman. See Erik Gross, “A Conversation with Jonathan Zimmerman: Evangelizing Liberal Education,” The Forum, August 8, 2019, https://www.goacta.org/2019/08/a-conversation-with-jonathan-zimmerman-evangelizing-liberal-education/. [↩]

- Throughout this report, we carefully distinguish between politics, partisanship, and ideology. Politics is defined through human relationships and turns on debates over who can or should hold power. Politics become partisan when individuals shape their views around a party or its agenda. Ideology describes how ideas and ideals shape political action. [↩]