I applied to serve in the 2021 South Dakota social studies revision process with some trepidation. It was clear by then that a movement opposed to anything its members deemed “critical race theory” (CRT) had gained ground. “Divisive concepts” bills proliferated in state legislatures across the country while South Dakota’s governor, Kristi Noem, made opposition to CRT a central part of her brand as a politician with national aspirations, despite producing little evidence that CRT was even being taught in K–12 classrooms. In fact, recent polls show that parents of school-aged children are not driving the anti-CRT movement and generally support the education their children currently receive—including education on difficult topics. A 2022 South Dakota Department of Education study found that almost all standards or educational practices being used in classrooms were already consistent with Governor Noem’s executive order banning divisive concepts.

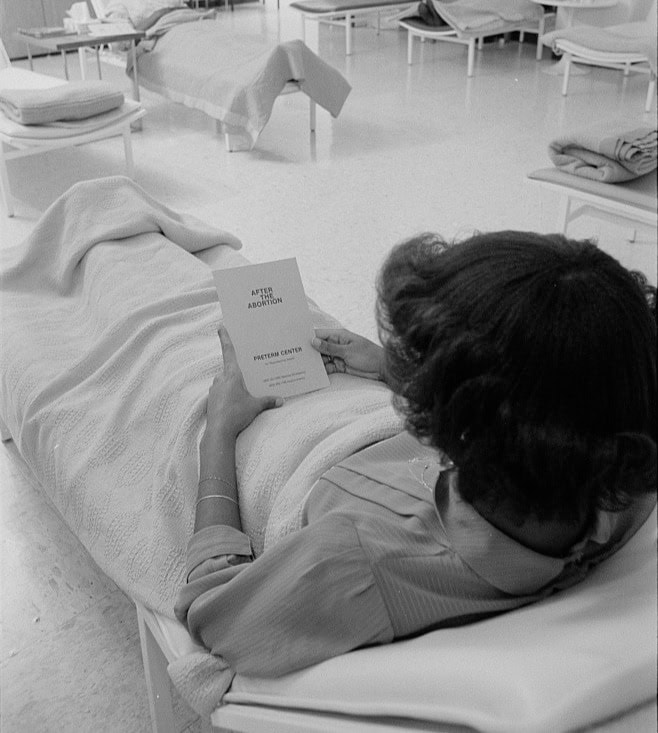

Political agitation against “divisive concepts” in the social studies curriculum has divided South Dakota along partisan lines. L. H. Bailey and Wilhelm Miller, Cyclopedia of American Horticulture(1900). Public domain.

But debates over standards are not just about facts and evidence. At heart, they are contests over rival visions of what the nation should be, and proponents of “divisive concepts” bills largely embrace the idea of American exceptionalism. In South Dakota, Governor Noem was one of the first significant politicians to sign the “1776 Pledge,” which begins by stating that “the United States is an exceptional nation whose people have always strived to form a more perfect union based upon our founding principles.” Locally and nationally, history education is at the center of US culture wars.

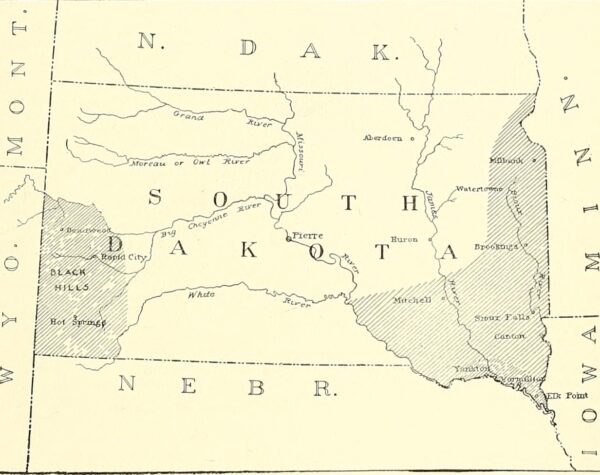

Despite the potential for controversy, I believed that I could positively contribute to the revision process as a historian and as a citizen. As a historian, I could share my subject matter expertise and insist on a nuanced set of standards that incorporates multiple perspectives. As a citizen, I wanted the process of standards revision to be transparent, thorough, and inclusive. So in the summer of 2021, I journeyed to the state capital of Pierre as a member of the Social Studies Work Group. Over eight workdays, I collaborated with educators, state representatives, businesspeople, and a representative from the South Dakota Department of Education (SDDOE). Together, we forged a new set of social studies standards for K–12 students that significantly improved on the previous version.

As a historian, I could share my subject matter expertise and insist on a nuanced set of standards that incorporates multiple perspectives.

Among the technical revisions and updated wording, the work group focused on two broad sets of changes. The first was to more fully include perspectives from South Dakota’s Indigenous peoples, the Oceti Sakowin Oyate. Here we relied on the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings (OSEU) for guidance. This document was officially approved and recommended, but not required, by the State Board of Education Standards (BOES) in 2018 (a 2021 poll found that OSEUs were taught in less than half of classrooms). Second, the work group integrated concepts from the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies Standards, which offers guidance on how best to include inquiry in the K–12 curriculum. Inquiry encourages the development of critical thinking, research, and writing skills that accompany content knowledge acquisition in a thorough social studies education. South Dakota’s 2015 standards incorporated some of these principles, but public input prior to the 2021 work group sessions indicated a desire for a more robust engagement with the C3 Framework. Both sets of changes were made in consultation with the SDDOE, which required every work group member to participate in training sessions on the C3 Framework.

In August 2021, the new standards were released to the public, but we found it was not the document on which we had all worked. The SDDOE had rewritten the standards behind closed doors, significantly undermining the efforts of the work group by removing numerous references to the Oceti Sakowin Oyate as well as an anchor standard—inquiry—based on the C3 Framework. My own contributions to the original document had focused specifically on the high school world history course. As I read through the new version of this section, I noticed that all references to Indigenous peoples—both Oceti Sakowin Oyate and global Indigenous peoples—had been removed. The changes were so significant that I requested my name be taken off the document.

The SDDOE provided little justification for their actions, and it remains unclear why the state government amended the standards outside of their own stated procedures. A poll of South Dakotans in late 2021 revealed how out of step the result of this unprecedented action was with public opinion, as 88 percent of respondents supported teaching Indigenous history in K–12 settings. What is clear is that the SDDOE’s intervention resulted in controversy. The South Dakota branch of the American Civil Liberties Union declared that the SDDOE’s actions were likely illegal. Indigenous education advocates organized the Oceti Sakowin March for Our Children on the state capital, and a majority of public comments submitted to the BOES opposed the state’s actions.

The censorship of the work group’s standards proved to be only the first step in a series of unprecedented actions by state officials designed to affect the outcome of the social studies revision process. Facing sharp criticism from Stanley Kurtz in National Review that even the SDDOE’s revised standards were “hopelessly compromised” by “hard-left activists,” Governor Noem suspended the normal standards revision process and eventually threw out the SDDOE’s 2021 draft standards entirely. She announced the formation of a second group, known as the 2022 Social Studies Standards Revision Commission (SSSRC), to create a new set of standards from scratch. The makeup of this group indicates the overt politicization of the process. The governor’s chief of staff, who has no background in education, chaired the group. Only three of the 15 members were practicing K–12 teachers—and one of them did not teach in South Dakota—indicating the marginalization of professional educators in the state’s new standards creation process. The only two practicing K–12 South Dakota educators on the commission have both since spoken out against the process and the results of the commission’s work.

The makeup of this group indicates the overt politicization of the process.

The SDDOE contracted William Morrisey, professor emeritus from Hillsdale College, to facilitate the SSSRC. In another unorthodox move, Morrisey wrote the draft of the standards before the commission even met. It therefore remains unclear to what extent the commission, appointed to draft standards, was actually involved in the process.

The exchange of educators for political loyalists did not stop there, but reached the BOES, which serves as the final arbiter of K–12 standards in the state. In May 2022, Governor Noem replaced an educator who had decades of experience on the BOES with a retired orthodontist. Sidelining educators led to a set of standards that fail to meet the basic criteria for social studies education.

The SSSRC released their draft standards in August 2022. Though the 128-page document more than doubles the number of requirements from the current version, the additions are not meant to increase student proficiency in history. The introduction states that inquiry has no place in a set of social studies standards. Instead, the action verbs in the proposed standards—describe, recite, explain—rely on rote memorization. Even the early grades are saddled with vast memorization of content, leading the South Dakota Educational Association to conclude that the new standards are age-inappropriate. To date, public reaction to the SSSRC standards has been overwhelmingly negative. Of the hundreds of public comments submitted in advance of the first BOES meeting in September 2022, 86 percent were opposed to the commission’s version of social studies standards.

The process and results of South Dakota’s social studies revision from 2021–22 reveal a pattern of troubling and politically motivated actions by the state’s government. South Dakota has one of the largest Native American populations in the country: their robust inclusion in the state social studies standards is imperative, not decorative. And basic historical thinking skills are vital to a rigorous social studies education. If the 2022 SSSRC proposed standards are adopted as written, the focus on rote memorization and the intentional neglect of historical skills development will be a serious detriment to South Dakota’s students. Further, throughout this process there has been a decided lack of transparency as the state government engaged in the unprecedented use of executive power to affect the outcome of the social studies standards revision process.

The SSSRC’s proposed standards vividly demonstrate that intentionally marginalizing educators in their creation results in standards that lack basic features of a rigorous social studies curriculum. Though the bureaucratic processes can seem byzantine, the politics can get ugly, and the end product might feel far from the cutting edge of historical knowledge, it remains critical that educators and historians continue to advocate for high-quality social studies standards.

Editor’s Note: The AHA sent a letter to the South Dakota Board of Education Standards on September 15, 2022, registering “strong concern” about the revisions process.

Stephen Jackson is associate professor at the University of Sioux Falls. He tweets @stomperjax.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.