I decided to run for local office on November 10, 2016. Twenty-four hours earlier, I had learned the outcome of the presidential contest while on a transatlantic red-eye flight to London. As our plane descended into Heathrow Airport on the morning after Election Day, I asked a flight attendant whether he had heard any news about the race. With a poker face, he told me in a near whisper that Hillary Clinton had conceded a few hours earlier. The news rippled through the cabin, with some passengers looking delighted and others looking ill. The poor crew members were on the job and could betray no emotion whatsoever.

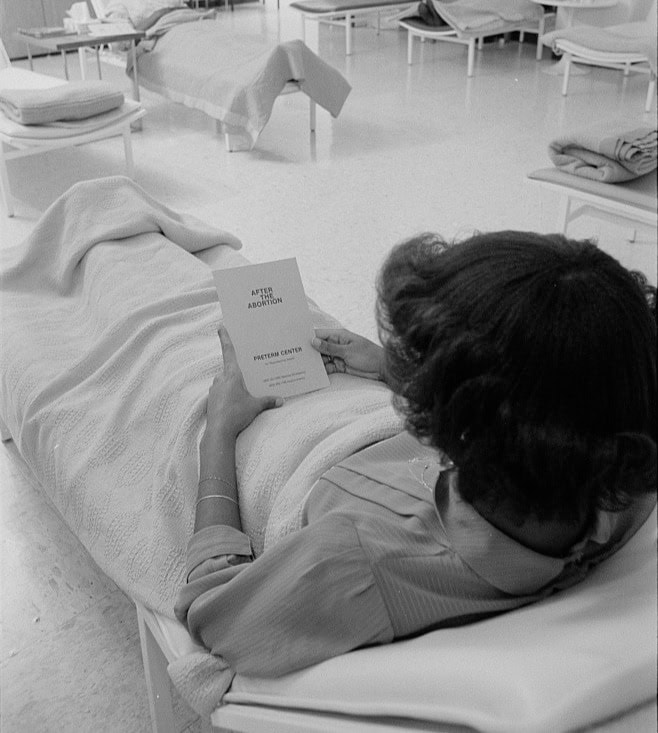

In 2017, Natasha Zaretsky ran for and won a seat on her local school board in Carbondale, Illinois. Steve Shook/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Until that time, I had never considered running for elected office, as I did not believe I had sufficient knowledge or skill to do so. But, like many other women, I found myself newly empowered by Donald Trump’s political ascent. If a real estate mogul and media personality could become president, then surely I could find a way to be of service in Carbondale, Illinois, my home for almost two decades. And while no one knew what would happen next, I predicted that in the coming period, it would be important for people to do what they could to defend the most vulnerable members of their communities—to try to make the places where they lived better, even as national politics grew more polarized and volatile. I also recognized that 2016 was turning out to be a truly historical year: both Brexit and Trump’s victory signaled a populist upsurge across the West. As a scholar, I knew that historians would be puzzling through the meaning of this upsurge for years to come. But sitting in my London hotel room, I realized that I wanted not to just watch history in the making but to become part of it, even in a small way.

I decided to run for the local school board. There would be an election the following April for four open positions on the board of District 95, the K–8 public school system. The district had excellent teachers and facilities, but it struggled to address the needs of a diverse student body. The student body is majority African American. Many students come from low-income households. But Carbondale is also a college town, home to Southern Illinois University, where some parents start fretting about their own children’s college prospects from the time they are very young. My two sons, aged eight and thirteen, were enrolled in the district, which technically made me a stakeholder. But that was not why I ran. Before 2016, I prided myself on being a laissez-faire parent when it came to the goings-on in the school district. As an educator, I trusted the teachers to do their best, and I bristled at parents who challenged their expertise. And I was alarmed at what I perceived to be the excessive anxieties of my white upper-middle-class parental cohort.

My choice to run for the school board had less to do with my status as a parent than with my knowledge of recent US history. Between the decisive defeat of Barry Goldwater in 1964 and the victory of Ronald Reagan in 1980, grassroots activists on the right, many of them women, recognized school boards as places where they could reclaim power and rebuild their movement from the ground up. In living rooms and at kitchen tables, they pursued incremental, small victories that eventually culminated in the realignment of American politics in the late 20th century. Now with the tables turned, progressives like myself needed to do the same slow and steady painstaking work. There would be no shortcuts or work-arounds.

My choice to run for the school board had less to do with my status as a parent than with my knowledge of recent US history.

I also predicted that, if I were elected, my work on the board would dovetail with my scholarly interests. That turned out to be true. So many of the themes I cared about as a historian—from racial and class inequality to gender politics and labor history to historical memory—came alive for me when I joined the board. How could the district narrow the racial achievement gap? How was it addressing the needs of gender nonconforming students? How could the district improve a strained relationship between the administration and the teachers’ union? What were students learning about American national identity in their classrooms? When I joined the board, themes that I had only read about became far less abstract. So, too, did the racialized poverty that divided my town between the haves and the have-nots. Behind closed doors, I heard firsthand the heartbreaking stories of students who came to school hungry, who were too exhausted to stay awake in class, whose families lacked stable housing. The dissonance between their experiences and those of my own children deepened my understanding of my town. I gained a new appreciation of the struggles of school districts like ours that worked to simultaneously provide for the most elemental needs of some children (such as food, heat, rest, and medical care) while convincing the upwardly mobile parents of others to reject the impulse to flee for a wealthier and whiter neighboring district with better test scores.

But first there was the matter of getting elected. The race was competitive: there were seven of us running for four open seats on the board. Except for a few days of knocking on doors for Barack Obama in 2008, I was a campaigning novice. But I did have certain advantages. I had more time than usual (I was on sabbatical in the spring of 2017) and enough money in my savings account to loan myself some initial campaign funds. I am an extrovert who enjoys meeting new people and is comfortable with public speaking. Also, I was running in a college town where I could be open about my progressive political leanings. The race itself was nonpartisan, but I didn’t pretend that I was anything other than a Bernie Sanders–inspired Democrat.

My real secret weapon was that I was not afraid to ask for help. And help I received, because universities and colleges are treasure troves of talent. Colleagues in the political science department helped me develop a plan for door-to-door canvassing. Artist friends designed campaign signs and stickers, and contacts in my faculty union put me in touch with a unionized print shop. My older son’s best friend was an aspiring filmmaker who made a 30-second campaign video we circulated on social media. I visited churches and community centers, organized a fundraiser at a local bar, and invited people to my house for phone banking, where I rewarded them with pizza, beer, and playtime with our new puppy. People were eager to pitch in, relieved to be able to do something in early 2017 other than doomscrolling. And campaign contributions came in too. Some of the money came from locals whom I did not know but who sent me checks with sticky notes cheering me on. Others came from old family and childhood friends from across the country who expressed their gratitude to me for running for office. These included people disillusioned by both parties, but who nonetheless grasped the crucial role that elections play in creating durable majorities, sustaining communities, and building social movements.

On April 4, 2017, five months after I first decided to run for office, I won a board seat. I even turned out to be the top vote-getter, prompting another winning candidate to tell me with a laugh that I had “run the table.” It felt good to win, especially as a rookie. And it was very cool to tell my kids that their mom would soon be sworn in as an elected official. It mattered to me that down the road, this would be part of their childhood memories, something they could carry with them into the future. I felt proud. At a moment of crisis, I decided to try something new and had prevailed.

My subsequent two years on the board (2017–19) were deeply gratifying ones. People sometimes ask me whether the experience made me less of an idealist, and the answer is no. Of course, there was the painful (if also predictable) realization that the deepest inequalities embedded in our schools could never be resolved by the district alone. But I also watched as teachers, parents, and administrators came together and tried to act in the best interests of children. My board service encompassed everything from the threat of gun violence and youth mental illness to teacher grievances and bilingual education, from how to recruit teachers who reflected the demographics of our student body to the hiring of a new superintendent. When I won the election, I told my father that I was scared that I would disappoint people. No one will fault you for failing, he told me, only for not trying. During my time on the board, I saw so many people trying to do good. Sometimes they succeeded and sometimes they failed, but bearing witness to the effort was profound. When I moved away from Illinois two years into my four-year term, I felt sad to say goodbye prematurely to the board and predicted correctly that I would miss the work.

People sometimes ask me whether the experience made me less of an idealist, and the answer is no.

That work had taught me a deeply personal lesson. Throughout my life, I always had struggled to ask for help from others. This time, I knew I had no choice. Colleagues, friends, relatives, neighbors, and strangers made me feel like I had the wind at my back. Thanks to them, I experienced the singular joy that comes from being part of something bigger than oneself. Once on the board, I gained a tangible understanding of just how much children paid the price for the enduring poverty and racial segregation that plagued our town. But unlike in the past, I now had a seat at the table: I could make decisions that made their lives better. Running for local office is a powerful democratic tool that we can use to look out for one another, gain access to real power, and imagine a different future.

Natasha Zaretsky is professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and served on the Carbondale, Illinois, District 95 school board in 2017–19.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.