Contents

Teachers’ Purposes, Priorities, and Favorites

Native American History

The Founding Era

Westward Expansion

Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction

Industry, Capital, and Labor

The Civil Rights Movement

A wide array of forces compete to determine the shape and content of US history curriculum: state legislators, state agency officials, district curriculum specialists, professional associations, educational publishers, and local parents, all while teachers would prefer to be left in charge of the details. Those details—what gets emphasized and what gets minimized—are an expression of those competing forces but with a heavy dose of individual preference.

Teachers’ Purposes, Priorities, and Favorites

To discern what teachers thought about the purpose of learning US history, the survey asked them to rate the importance of 20 carefully phrased learning outcomes they might have for their students. Some of these are in essence “skills”; others “goals and values.” Among goals and values, we purposefully included options that signaled various ideological positions, from progressive multicultural to civic nationalist to critical antiracist to centrist optimist to patriotic exceptionalist. This section was designed to reveal what teachers think their students should get from a US history class, in terms of both the narrative arc and core competencies.

These were the prompts and response options provided:

| How important are the following skills for US history students to learn in your class? | How important are the following goals and values to teaching US history? |

|---|---|

| Developing critical thinking skills | Presenting US history as a story of violence, oppression, and/or injustice |

| Teaching students to analyze primary sources | Presenting US history as a series of conflicts over power |

| Embedding core knowledge of key events, people, and eras in American history | Presenting US history as a complex mix of accomplishments and setbacks |

| Teaching students to build arguments using evidence from primary sources | Presenting US history as a consistent fulfillment of the promises of the nation's founding |

| Teaching students to think in terms of causes and effects | Presenting multiple sides of every story |

| Teaching students to understand the contingency of historical events | Making connections to the present |

| Introducing students to historiographical debates | Instilling civic pride in the nation |

| Getting students to articulate how they feel about the past | Building an appreciation for diversity |

| Teaching students how to do research | Instilling core knowledge of national heritage |

| Teaching students how to write a thesis-driven essay | Focusing on challenging/controversial topics |

| Developing informed citizens for participation in a democratic society | |

| Expecting students to confront the role of racism in our nation’s character | |

| Cultivating an appreciation of the United States as an exceptional nation | |

| Helping students see the role of God in our nation’s destiny | |

| Building a shared sense of national identity among students across social groups |

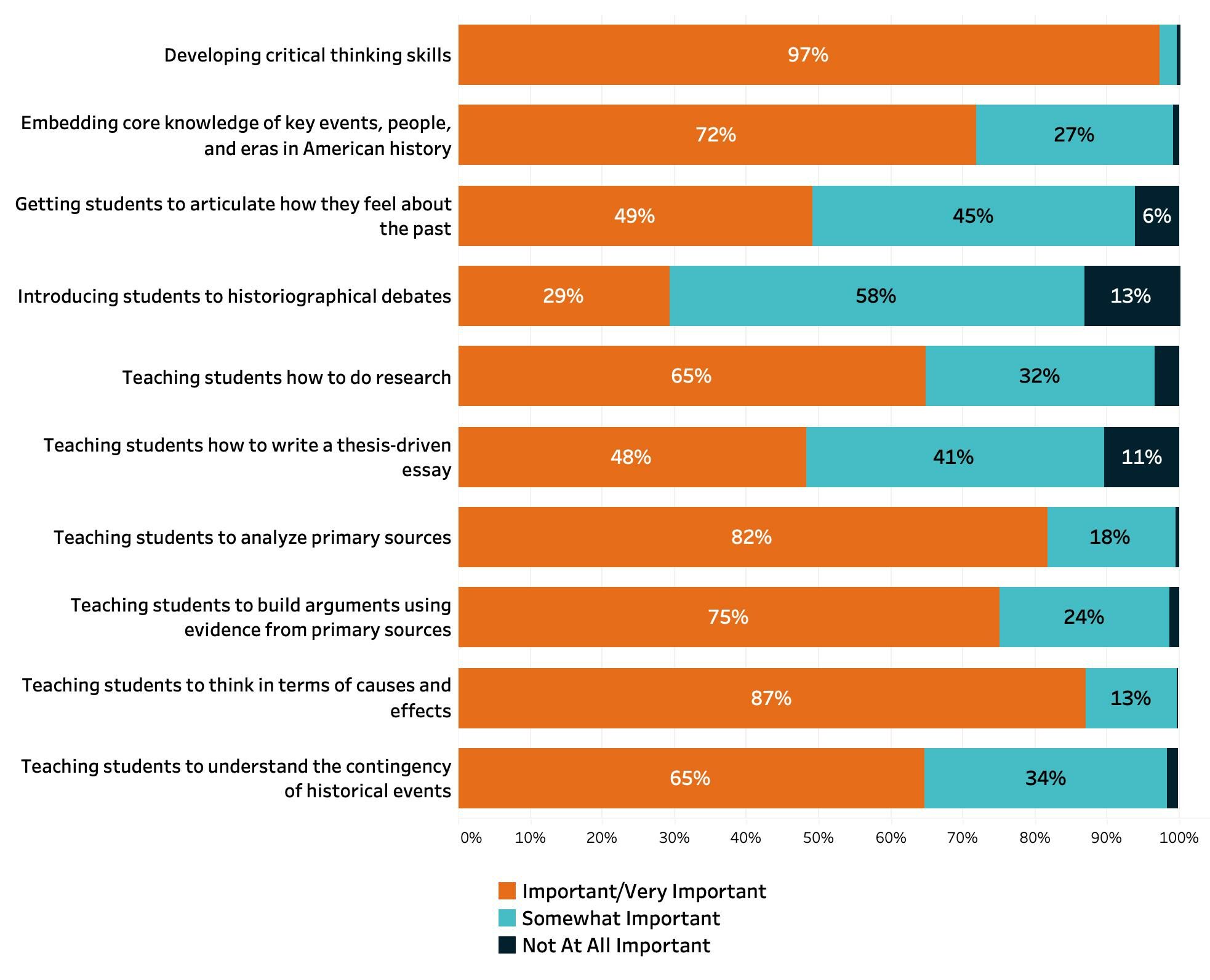

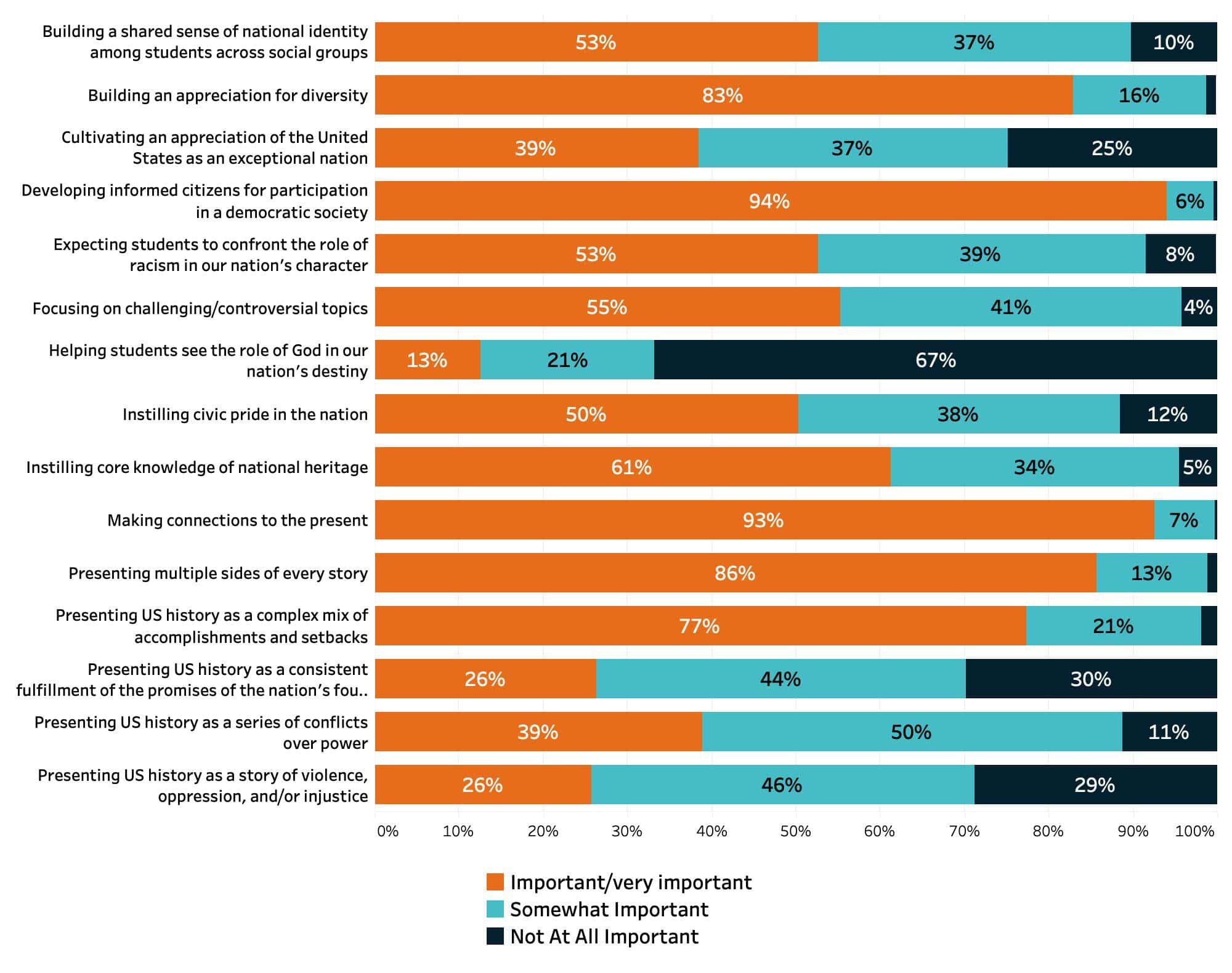

The data from these questions tell a clear story, with some regional variations (Figs. 30 and 31). Surveyed teachers almost unanimously see the goals of critical thinking (97 percent), democratic citizenship (94 percent), and making connections to the present (93 percent) as central to their approach to teaching US history. Close behind were the goals of teaching cause and effect (87 percent), presenting multiple sides to every story (86 percent), and analyzing primary sources (82 percent). Less popular learning goals included “seeing the role of God in the nation’s destiny” (13 percent), framing US history as “a story of violence, oppression, and/or injustice” (26 percent), or as a “consistent fulfillment of the promises of the nation’s founding” (26 percent).1

Fig. 30: Skills Rated as Important/Very Important by Teachers (n range = 2,187–2,254)

Fig. 31: Goals and Values Rated as Important/Very Important by Teachers (n range = 2,126–2,253)

The specific contours of teacher responses in each state point to distinct cultural and political contexts. Connecticut teachers were more likely than teachers in other states to rate research and writing skills as especially important. In Alabama, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia, more teachers favored core content knowledge than in other states. Alabamans, Texans, and Virginians were more likely to see a value in identifying the United States as an exceptional nation (64 percent within those three states compared with 46 percent in the other six) and to see the role of God in the story (36 percent versus 17 percent in the other states). Fewer teachers in Colorado, Connecticut, and Washington (50 percent) rated civic pride in the nation as an important value as compared with other states (66 percent).2

Though less pronounced than state contrasts, there was some variation in responses according to locale type, with rural and city teachers differing by as much as 10 percentage points regarding how much negative or positive emphasis should be given in US history. Forty-five percent of urban teachers rated “violence, oppression, and/or injustice” as important, as opposed to 35 percent of rural teachers and 34 percent of town teachers. Seventy-one percent of urban teachers agreed that it was important for students to “confront the role of racism in our nation’s character” as compared with 61 percent of rural teachers and 56 percent of town teachers. “Instilling civic pride in the nation” earned approval from 70 percent of rural teachers but only 60 percent of urban teachers. Sixty percent of rural and town teachers saw value in “cultivating an appreciation of the United States as an exceptional nation,” compared with 50 percent of teachers in cities and suburbs. These variations notwithstanding, what is most striking among these data are their general similarity across environments—an index of a common national teaching culture among history educators.3

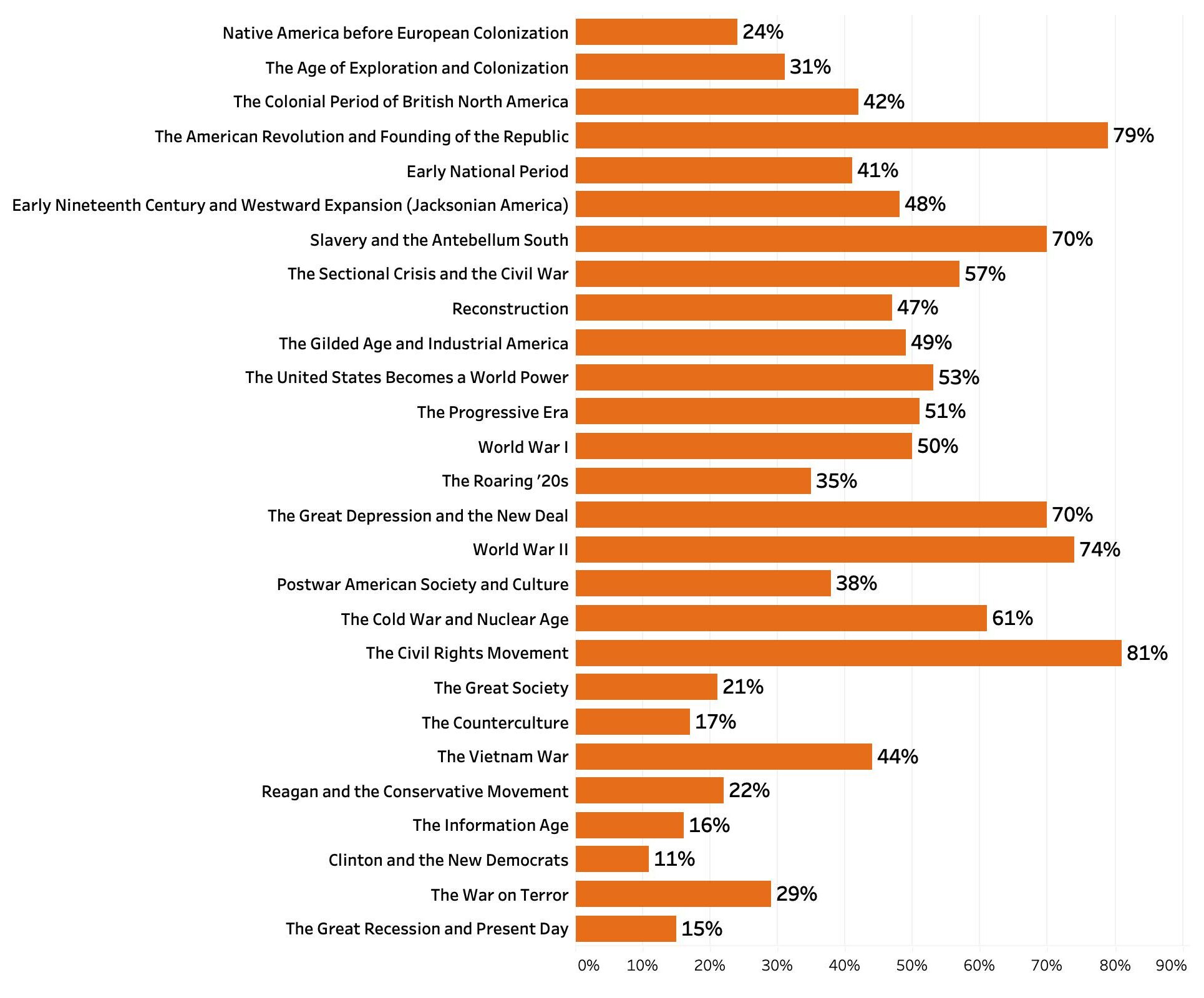

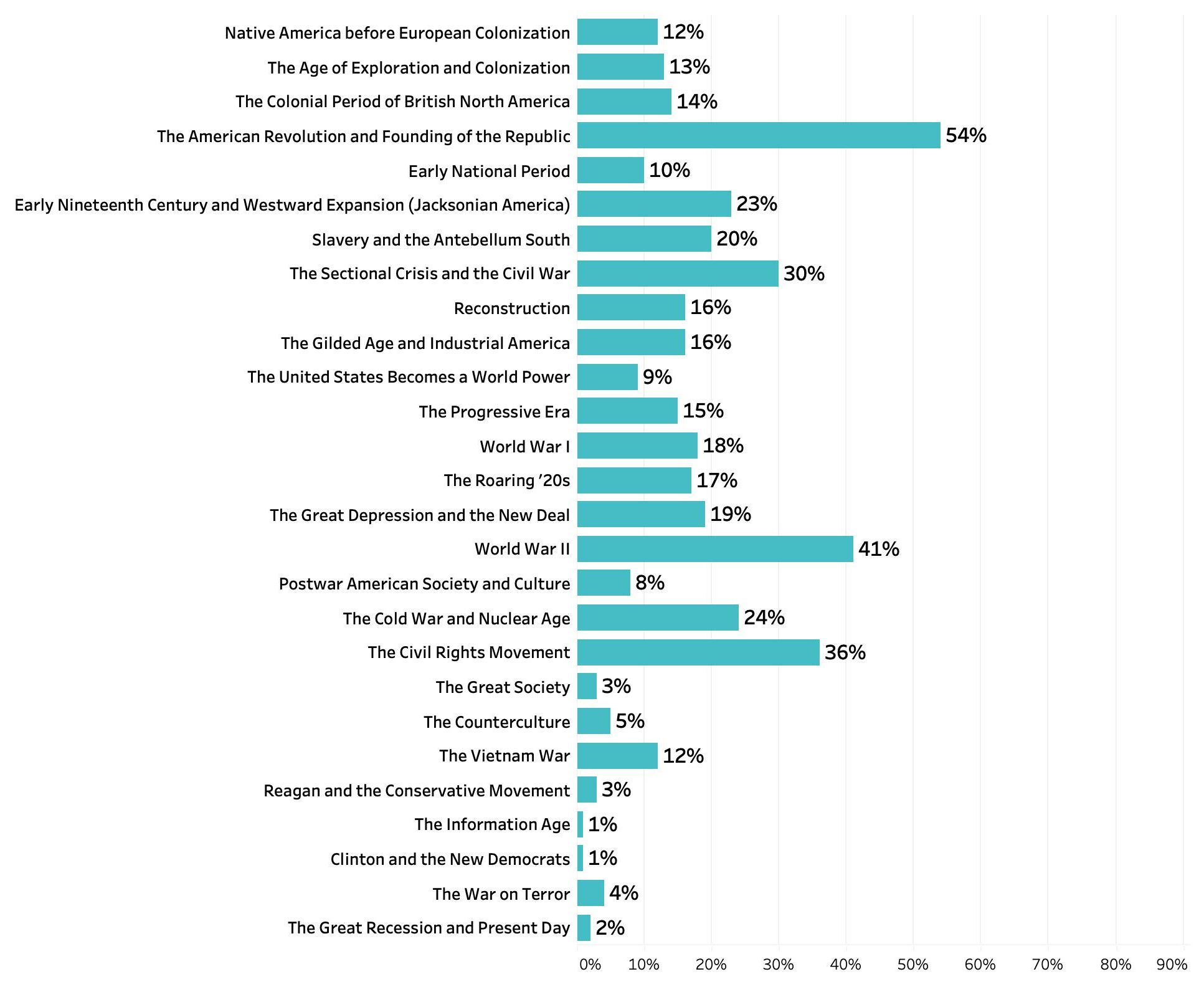

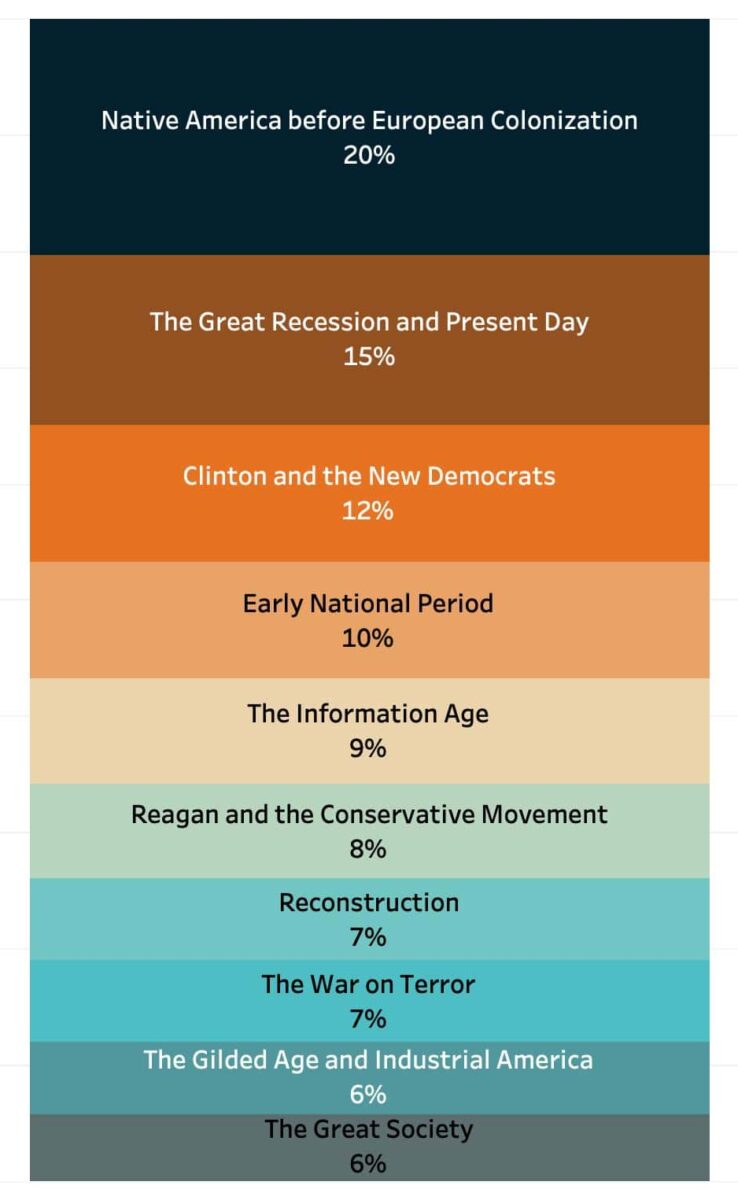

Focusing more tightly on content, we also asked teachers which topics and eras were top priorities for coverage and which were their favorites to teach. Their answers (Figs. 32 and 33) show clear points of common emphasis: the American Revolution, the Civil War, World War II, and the Civil Rights Movement. This might be read as a playlist of America’s greatest hits: rejecting monarchy, abolishing slavery, fighting Nazis, and ending Jim Crow. But inevitable triumph isn’t the note that teachers strike when they say why they love these topics. Some teachers cite the value of learning about heroes and heroics. But others stress the notion that these events were exciting, dramatic turning points, that they were full of contradictory and complicated politics, and that something about what Americans are today can’t be understood without comprehending these past events.

Fig. 32: Topics Teachers Describe as High Priorities for Coverage (n range = 590–2,401)

Fig. 33: Teachers’ Favorite Topics (teachers were limited to only three choices; n range = 1,532–2,387)

This picture doesn’t square with ideological caricatures of politicized classrooms. Teachers (and the resources they use) tend not to align neatly to a partisan “take” on American history. When they succeed, they do so by connecting students with evocative primary sources, promoting patient and empathetic readings of multiple perspectives, and instilling a sense of the contingent and contested nature of historical events.

When curricular materials falter, it’s typically because detail and complexity have been sacrificed in pursuit of streamlining. Sometimes, these simplifications betray an ideological bias, tacking toward moralistic, fatalistic, or presentist impulses. Too many lessons encourage students to judge whether something was a “blessing or a curse,” a “hero or a villain,” or is “with us still today.” In other cases, specifics have been blurred into a backdrop behind the main stage of skills development, with nonfiction literacy and evidence-based argumentation prevailing over the stakes and textures of a historical episode.

Undoubtedly, many weaknesses in curriculum are inherent to the task at hand; to teach the typical middle or high school US history course, teachers are obliged to skim the surface of an impossibly deep pool of scholarship and source material. All teachers must be ruthless editors and assemblers, and they are unlikely to be equally expert in every topic. Surveyed teachers were not shy in admitting where they felt the need for more training (see Fig. 34).

Fig. 34: Topics Teachers Identified As Areas Where They Lack Sufficient Background and Support (n = 668)

The following sections summarize the strengths, weaknesses, and patterns in various kinds of curricular materials focused on six topics: Native American History; the Founding Era; Westward Expansion; Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction; the Gilded Age and Progressive Era; and the Civil Rights Movement. These topics fall within the standard span of chronologically organized US history, have been known to provoke politicized controversy, or have been perceived by historians as areas where there is likely to be a lag or gap between scholarly consensus and broader public knowledge. We began by assuming that K–12 materials would not reflect the latest theoretical disputes within every academic subfield, but that classroom accounts of US history should be free from factual errors and ideological distortions. We tracked factual content, looked for discredited interpretations, and took note of any distorting ideological emphases. Our judgments are meant to highlight patterns of strength and weakness across a vast archive of representative material, not to scorn or praise.

Between Mythbusting and Historiography

Some subsets of curricula (and a few state standards) adopt a self-aware perspective on the construction of historical knowledge. Some of these gestures—as in Florida standards’ call to have students “describe the roles of historians and recognize varying historical interpretations,” or a Washington unit’s promise to “consider how stories about historical events in US History have changed over time and why”—would likely be appreciated and applauded by historians.4 The modern historical discipline would be unrecognizable without the fundamental insight that historical interpretation is itself historically constructed.

But what is common sense among historians is only subtext in most curricula and is notoriously tough to teach.5 Metacritique of storytelling is rarely as compelling as a good story. The various inquiry activities or research projects that direct students to construct an evidence-based argument using primary documents (such as C3 Inquiries, DBQ, SHEG, and so on) at least imply that history is an ongoing series of investigative exercises with diverse findings, rather than a fixed monologue about the past. Missing from these modules, however, is an appreciation for how historians argue over, reconcile, or synthesize diverse interpretations, and why (and when) certain accounts become a matter of consensus while others fall out of favor. Historians’ term for this terrain—historiography—is buried in most K–12 curricula. Indeed, among the 10 skill sets whose importance we asked teachers to rate, “introducing students to historiographical debates” was the clear loser, with only 21 percent of teachers rating it as important or very important.6 There are certainly glimmers of historiographic consciousness in some materials, and pedagogical initiatives are attempting to provide teachers with sturdier modules for exploring the topic with K–12 students.7

More often, however, curricula that aim for the concept of history-as-historical-construction land somewhere outside of the historiographic conversation, striking a generically skeptical posture toward a “mainstream” or “dominant narrative” that is in need of disruption or redirection.8 Such provocations tend toward imprecision, unhelpfully muddying the difference between what historians mean by an “interpretation” (an evidence-based, narrative argument about the causes or implications of social change) and how the broader public applies that term (well, that’s just your interpretation—your opinion).

Among the topics we appraised, the American Revolution and the Civil Rights Movement stood out as the eras most likely to include some historiographic self-awareness. Surveyed teachers made multiple mentions of their commitment to telling a more complete, updated account of these topics than had existed before, and some instructional materials on these subjects included explicit discussions of how distinct generations of historians developed new and competing arguments. Beyond their richness as mature subfields, why would these two eras earn more nuanced treatment in curricula? Doesn’t their role as totems of civic nationalism and moral authority imply the opposite—that they are ripe for sentimentalism, distortion, and instrumentalization? It seems plausible that the civic weight assigned to these subjects are in fact what whets the appetite of the broader public for more sophisticated understandings, directing some historians toward public scholarship. The revolution and civil rights attract big events and big funders, financing opportunities for historians to inject fresh snippets of academic debate into the cycles of media, museums, memorials, movies, and curricular material that cover these topics. This model may be difficult to follow for more neglected topics. Native American history, while certainly an interest for many and a matter of political importance for contemporary tribal nations, sits uncomfortably alongside national civic sensibilities, while events since 1970 merge directly into contemporary political disagreements, a scenario that many teachers prefer to avoid.

Native American History

Of the topics appraised by the AHA research team, curricular coverage of Native American history is the most likely to blur into generalities and the least likely to reflect recent scholarship from professional historians. Surveyed teachers confess to feelings of inadequacy on this topic.9

In standards and curricula, coverage of Native Americans tends to cluster in a few key moments along the traditional arc of the US history timeline: precolonial North America; the era of encounter and colonization; treaty-making and Indian removal during the pre–Civil War era of US westward expansion and annexation; and the Plains Wars of the 1860s–90s. Coverage of Native American history in these particular eras is usually unobjectionable insofar as accuracy is concerned, but a tendency toward generalization predominates. In state standards, for example, all Native Americans tend to be grouped together (often in a “such as” list alongside women, African Americans, and other “minority groups”) that have “contributed to” or been “affected by” some historical event. Local curricula repeat these broad strokes—referring to a “Native American way of life,” for instance.10 In other cases, a particularly vivid episode (the Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek Massacre, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School) stands in for a diverse range of temporally adjacent Native histories.11 This approach is preferable to neglect, but curricula seldom include clear guidance about the relative representativeness of a given event with respect to broader understandings of Native history during a particular era. In a handful of curricular materials, an account of the first half of US history somehow is given without any direct mention of Indians.12

Our research corroborates findings by other scholars detailing the sharp drop-off of coverage of Indians after the close of the Plains Wars.13 A particularly blunt summary in an Alabama unit plan sums up the implied thesis of many curricula: “Conquered, the Native American way of life is all but lost and assimilated into a new American Nation.”14 Exceptions appear in the civil rights era, where the American Indian Movement notably (but infrequently) receives mention. Time devoted to other 20th-century topics—the Indian Reorganization Act (1934), the Indian Relocation Act (1956), the mobilization of Indian soldiers during World War II, or urban Indian communities—is rarer but tends to appear when making a self-conscious attempt to include Native American history across multiple units. If measured simply by the distribution of expository coverage of Native history, US history textbooks reinforce the theme of Native disappearance in the 20th century. Still, 21st-century textbook authors and editors clearly consider Native Americans to be significant historical actors, threading a throughline of maps, images, and special sections covering turning points for Native people in North America. In some cases, paid curricular resources provide teachers and students with detailed histories of specific events that are less commonly cited in standards or broad timelines.15

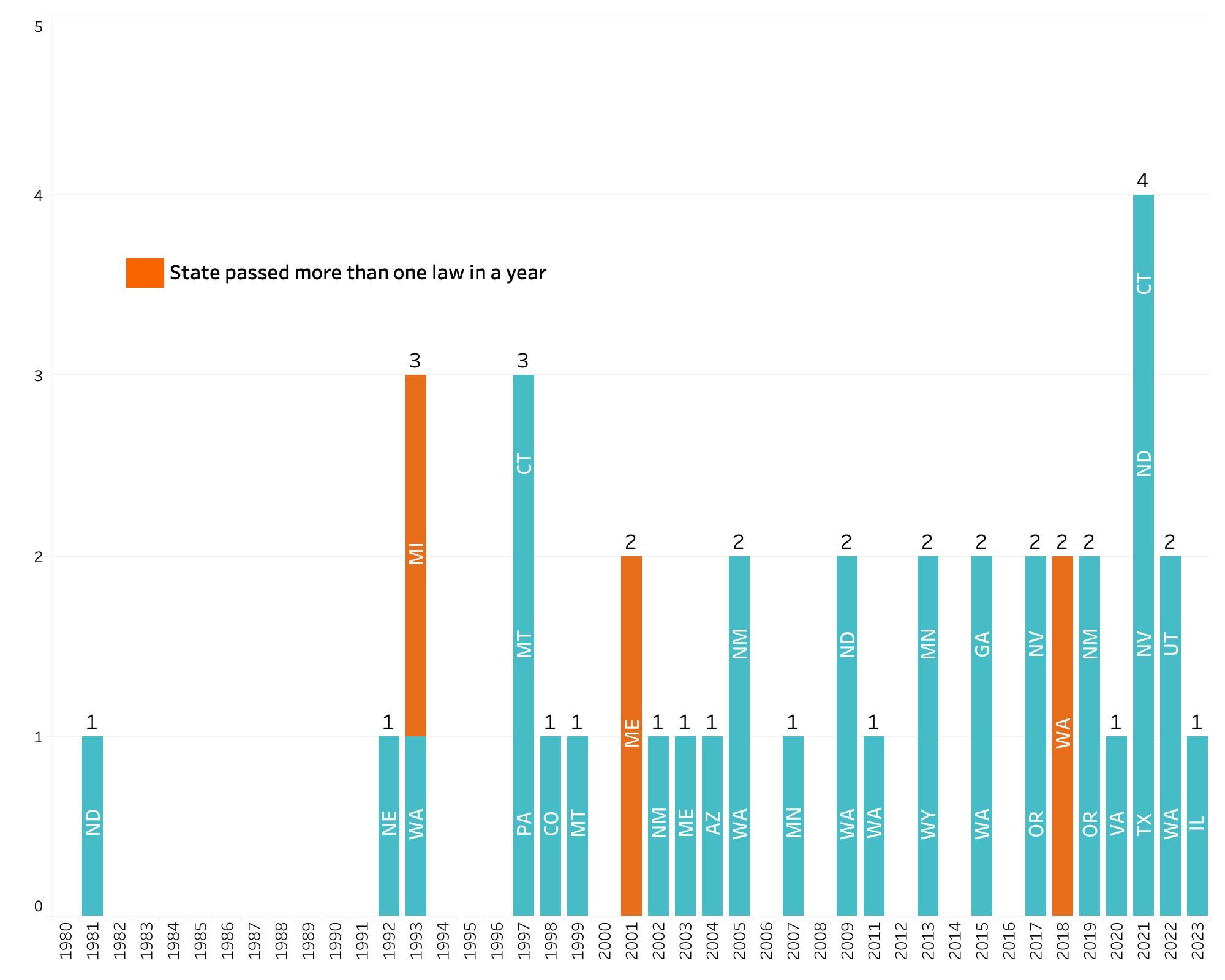

One of the most powerful antidotes to the tendency toward the abstract Indian is the required study of state and local history. State history mandates in some places force curriculum into exceptionally specific (and by extension, nuanced and textured) treatments of Native Americans as local peoples with rooted histories in a particular place (Fig. 35). The TEKS, for example, have only broad mention of Indigenous topics in the US history standards but specify coverage of local Native groups in 4th and 7th grade Texas history.16 Virginia’s SOLs likewise show efforts to ground Native history in local contexts.17 States with a substantial contemporary presence of federally recognized tribes and Native populations are even likelier to reserve more curricular time and space for Native American history. Colorado, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Washington, and Wyoming all distinguish themselves by including a visible strand of Native American history in their state standards or legislating a curricular inclusion.18

Fig. 35: Legislation Mandating or Encouraging Instruction on Native American History in Social Studies, 1980–2023 (n = 39)

In state standards that arrange subject matter chronologically, Native people typically appear in the first named unit of study, a massive span stretching from precolonial Indigenous civilizations of the Americas to the era of European colonization. Unfortunately, a short unit at the opening of a middle school academic year is often the subject’s only occasion for advanced study within US history courses. Twenty-four percent of teachers identified this era before colonization as among the most difficult to cover—the third most cited among all topics.19 Thirty-eight percent of those acknowledged that their difficulties were due to a lack of college coursework and supportive resources. Some teachers said that they simply “need more content knowledge” and “updated materials.”20 As one Iowa teacher lamented, “I want to make [Native history] a basis for all units and just don’t feel I do it justice.”21 Others sensed a disjuncture between archaeological and historical modes of interpretation, with one Washington teacher citing “the lack of precolonial texts” as confounding their construction of “compelling narratives.”22 Others still “struggle with how specific the learning needs to be.”23 As a Pennsylvania teacher put it, “This is such a long period of time that spans an entire hemisphere. . . . Figuring out what to include is overwhelming.”24

More complete attempts to embrace this immense topic deploy geography to specify and locate Indigenous groups by region and to describe how distinct physical environments influenced Native societies.25 Most textbooks open their Indigenous civilizations unit with an ethnolinguistic map of the continent’s various groups, but such maps tend to present a snapshot of 1492, and curricula will refer to prior eras as broadly “prehistoric.”26 More nuanced curricula also go some way in upending stereotypes of the “ecological Indian,” noting that Native groups transformed North American landscapes at least as much as they adapted to them.27 Guidance from state standards occasionally gestures toward the diversity of Indigenous America by “highlight[ing] the rich culture that existed in the Americas prior to colonization,” for example.28 But teachers in states with content-detailed standards clearly notice the relative vagueness of Indigenous history as compared with other topics. Nearly every teacher from Texas and Virginia who noted difficulties covering precolonial Native America cited its absence in state standards. As one Texas teacher quipped, “It’s not covered on the STAAR test so it ‘isn’t important.’”29

Stronger curricular guidance treats Native history with the dignity of specificity, naming Native groups and anchoring them in regional geography. In curricula covering colonial North America, Native groups are incorporated quite frequently, and individual polities and people do indeed get named and narrated: nations like the Wampanoag, Huron, Mohawk, Iroquois; figures including Metacom, Powhatan, Pocahontas. Still, Europeans are more likely to be granted their regional and cultural diversity (even when isolated to English ventures), while Native nations are collapsed into a single entity. Native groups may even be paired for analysis with other non-Europeans, as in prompts that ask, “What motivated freed Africans and Indigenous people to fight on behalf of the Patriots or the British?”30 Gestures toward disaggregation provide a better start, such as comparing different colonial approaches to relations with Native groups in North America.31 But even here, assumptions that colonists called the shots speed past an opportunity to explore the political and commercial conduct of distinct Native groups. Dominant themes in the past generation of historiography on Indigenous America, including the political agency, diplomatic leverage, and sovereignty claims wielded by Native polities deep into the era of Euro-American colonization, lie dormant in many K–12 expositions of Native history. 32

Problems of abstraction and timelessness in Native history have not been solved by various gestures of sensitivity, sympathy, or a decolonized pedagogy.33 Debates both within and between distinct disciplinary approaches to Native North America occasionally echo across K–12 curricula; framings that some Indigenous studies scholars may find acceptable might be resisted by some historians and vice versa.34 On the continent’s earliest human inhabitants, textbooks offer recaps of the latest archaeological evidence about Clovis and pre-Clovis cultures and migrations via land bridges, glacial, and coastal routes.35 Elsewhere, some curricula cloud Indigenous history in mists of uncertainty, as in one big city curriculum that centers Indigenous creation stories while disavowing the question of how the Americas were populated, asserting that historical answers “are still unknown.”36 In another large district, recently introduced curricula reinvest in essentializing depictions of Indigenous and “Judeo-Christian” civilizations as motivated by underlying theological approaches to land use: Indians as “symbiotic,” “cyclical” stewards of the environment and European settlers as inherently obsessed with “dominion.”37 Some recent state standards proposals invoke Indigenous studies as part of a mission of revaluing “marginalized perspectives” and “non-dominant” narratives but articulate no specific historical content about Native people.38 While perhaps well-intentioned, these approaches obscure the political, cultural, and material contexts that shaped diverse Native American societies and empires.

The framing of Native history as a moral quandary for contemporary Americans is a recurrent theme in classroom coverage, expressed clearly in the various essential and guiding questions that teachers pose or are encouraged to pose to their students.39 Sometimes these are clumsy rankings or flat binaries, as in an assessment that asks, “Who colonized the New World Best?”, a debate on whether “Sitting Bull [was] an American Hero,” or a resource that asks students to choose whether they want to make a Wanted poster or a Hero poster for a Comanche war chief.40 Attempts to squeeze Native history into civic frames are common, as in a prompt that asks how America was “a land of political, economic and social opportunities for indigenous peoples.”41 Elsewhere, district guidance awkwardly encourages teachers to take a mythbusters approach, asking students to surface their own stereotypes about Indians in order to demonstrate that Native history has been distorted.42 In other cases, questions about Native history are posed as policy issues to be debated: “Should the United States have allowed American Indians to retain their tribal identities?” “Have Native Americans been treated fairly by the United States government?” “Why do you think the government does not give back the stolen land to the Native American nations it was taken from?”43

In more than a few instances, questions about Native history take an affective turn.44 Some districts have developed lessons around progressive civic rituals, asking students to design their own land acknowledgment or to fill in the blanks on a premade template.45 Occasionally, historical Indians are recruited as a set of perspectives through which to evaluate contemporary civic questions. Having students use Native American history to decide whether they “want to be part of the environment or dominate the environment” is likely asking too much of students and of Native history.46

Placing episodes of Native American history within larger thematic or comparative units has the potential to move teachers and students away from civic meditations, but here Native American histories also get divorced from their political contexts. Comparing “Native and Mexican American struggles” or whether “Native American and African American experiences [were] similar in nineteenth-century America” might lead students toward the discovery of unique and contrasting histories. But in listing optional examples of a “struggle for equality over time,” placing Wounded Knee alongside the Seneca Falls Convention and the Freedom Riders likely stretches the thematic tent too far.47

More successful attempts at thematic organization take seriously the continuities and consequences that run between successive eras of federal Indian policy and Native social and political life today. A Connecticut unit takes a long view, directing teachers to trace “shifts in policy and social opinion . . . that led to removal in the 1800s and relocation in the 1950s and the impact of these forced migrations . . . reservation sovereignty and the assimilation efforts both desired and forced.”48 As with other topics we appraised, stronger lessons on Native history deploy perspective-taking as a constructive route to understanding the historical contingencies and cultural contexts that defined moments of encounter or conflict. These can appear reductive, as in activities that ask students to create fictionalized journal entries or fill-in speech bubbles for both wagon train settlers and Plains Indians in the 1840s.49 But insofar as they go beyond the initial act of imagination and invite students to read about the outlooks, interests, ambitions, and anxieties that individuals brought to a crucial moment, this is a step in the right direction. More sophisticated lessons put students directly among Native and US perspectives. A lesson in Iowa on the Horse Creek Treaty and Fort Laramie Treaty asks students to examine the historical peculiarities and civic legacies of 19th-century treaty-making.50 Some lessons enrich the era of removal by taking competing perspectives within Native polities seriously. A unit that asks “What path offered the best chance of survival for the Cherokee in the Early 1800s: staying in their original territory or removal to the West?” offers multiple points of view from within a single Indian nation.51 In contrast to the tendency to assemble a list of Native leaders into a portrait gallery of military resistance, lessons like these give teachers time and space to treat individual Indigenous leaders as historical actors facing complex and contested decisions.

The Founding Era

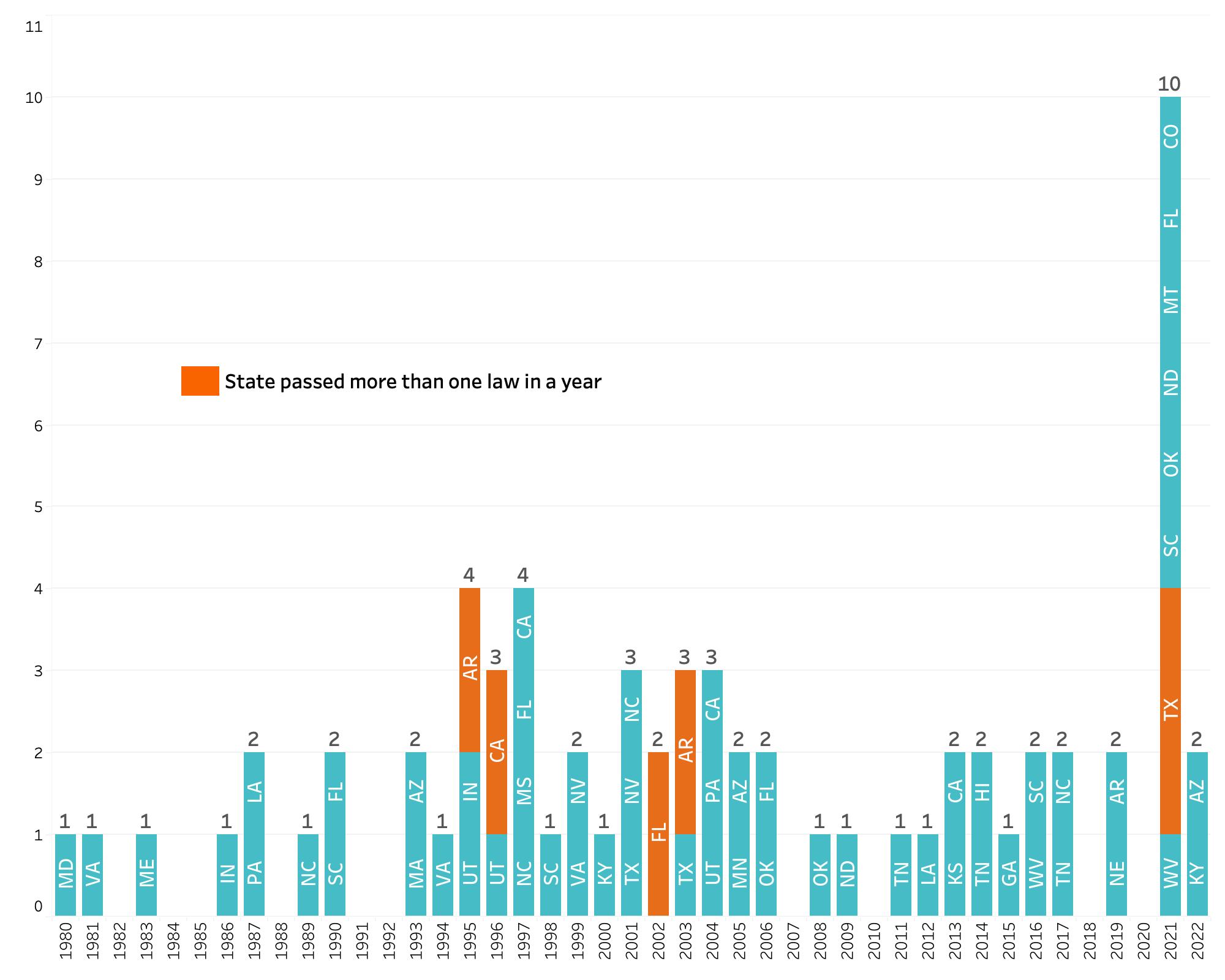

Of the six topic areas we appraised, the founding era is most readily recruited for acts of popular and civic memory. It is the top producer of recognizable historical figures (Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Hamilton), core texts (the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and Bill of Rights), and political watchwords (freedom, democracy, equality). For state legislators, founding documents are something like a renewable political resource. They are the one set of primary sources that earn explicit mention in legislation aimed at shoring up civic education or patriotism among the young (Fig. 36).

Fig. 36: Legislation Mandating or Encouraging the Study of Founding Documents, 1980–2022 (n = 69)

Prominent civic education nonprofits benefit from these waves of attention, producing a high volume of K–12 curricular content that speaks specifically to the founding era. iCivics, the Bill of Rights Institute, and the National Constitution Center provide resources frequently cited by teachers. Over half of surveyed teachers named the American Revolution and founding era among their three favorite topics to teach—the highest of any subject area. The founding was also the second highest ranked topic (after the Civil Rights Movement) for high-priority coverage. Asked to explain, teachers most cited the notion of a civic origin story. As one Connecticut teacher put it, learning about the founding is “knowing what being American was supposed to be and how our government was set up.”52

Historians of the revolution and early republic have periodically had difficulty squaring their view of a dynamic and diversifying subfield with the folk enthusiasms and civic rationales that have kept the founding era alive in K–12 curriculum and popular culture.53 Since the 1990s, a steady production of consumable histories of the revolutionary generation, including bestselling biographies, HBO miniseries, and a hip-hop Broadway musical, has been fed by the work of some historians while drawing sharp criticism from others.54 In the second half of the 2010s, the traditional choreography for public fights over the founding shifted, with some progressives reviving formerly impolite stances against the founding itself.55 The most prominent critical take was the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project.56 Conservatives seized on the publication’s civic provocation—that Americans should equate their nation’s “true founding” with slavery and racism.57 As the titles of several rejoinders made clear—President Trump’s 1776 Commission, Hillsdale College’s 1776 Curriculum, and the 1776 Unites Campaign—some conservatives sought to reassert the virtue and primacy of the revolution against its detractors. The ensuing culture wars, which included 11 state bills that singled out the 1619 Project for prohibition, proceeded without addressing the question at issue: What version of the American founding were students actually learning?

In state standards with specified chronological content, the founding era is never absent. In some cases, the founders even earn a quotation in the introductory statements of state education agencies, as officials invoke free self-government to justify the function of social studies education.58 In many states, the era gets a double dose of coverage, with civics and government classes dwelling on the founding and often assessing content knowledge in a state-mandated civics test (on the books in 18 states).59 Civic imperatives weigh heavily on the structure of some textbook and curricular units, pitching toward a Constitution-centered exposition. (The widely used iCivics curriculum refers to its revolutionary-era material as the “Road to the Constitution.”60 ) In some cases, the pressure to make the era’s events relevant to civic questions or contemporary issues produces awkward framings: “What has changed since then? What hasn’t?” Clumsy jumps to the present can be especially jarring in C3-style inquiry arc lessons, which are designed to end with a student-designed plan to “take informed action.” One Washington lesson on the dynamics of loyalty and opposition during the revolution ends with students being asked whether they will stand or kneel the next time the national anthem is played or Pledge of Allegiance is recited.61 In another, an inquiry centered on the Boston Tea Party is meant to prepare students to “identify an example of injustice in their school or community.”62

While many instructional materials instill a sense of drama in the lead-up to independence, the sudden shift to founding documents after the revolution often drains the early republic of its verve.63 As a Washington teacher explained, the early republic “is the unit that I teach civics and government.”64 The “3 branches of Government, Electoral College, 3/5 Compromise, Bill of Rights, impeachment, etc.” was as much as one Alabama teacher said they had time for once past the revolution.65 The early national period was far less popular than the revolution among surveyed teachers and selected as challenging by 32 percent. Teachers cited the difficulty of convincing students that “the growing pains . . . [of] being a brand new nation” was in fact a “big deal.”66 Others had trouble getting themselves excited about the era. In the words of a Virginia teacher: “War of 1812, Era of Good feelings? Just skip ahead to Jackson.”67

As “first half” US history topics, the American Revolution and early republic suffer when course sequences split content between middle and high school. In at least 23 states, advanced study of the founding era is not mandated at the high school level. This might account for some noticeable limitations in coverage. Seen from one angle, curricula on the revolution remain anchored in traditional modes of historical narrative, with a focus on elite political actors, pivotal moments of rebellion, the military chronicle of the War for Independence, and a focus on founding documents. The Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights are sometimes accompanied by excerpts from Common Sense, the Articles of Confederation, the Federalist Papers, Washington’s Farewell Address, and Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre. Textbooks echo these notes by including the standard documents in special sections or back matter. The curricula across our sample states show broad agreement regarding the main characters, events, and documents worthy of coverage.

Consensus doesn’t preclude nuanced treatment, however. Historians might wonder at the persistence of “salutary neglect” as a conceptual frame for 18th-century British North America, but they would find less to argue with in the many lessons that capture the competing perspectives, contingent decisions, and escalating misunderstandings that took colonists from resistance to rebellion to independence.68 Indeed, when we asked surveyed teachers to articulate what they felt was most worth remembering about the era, an emphasis on contingency and complex causation prevailed—more so than in their discussion of other topics.69 Teachers remind students that “it was a complicated, divisive time” and “that it wasn’t a foregone conclusion” with “no guarantee of success when it all started.”70 The notion of “multiple perspectives” can come across as something of a shallow slogan in social studies. But in some units on the American Revolution, the different perspectives among British and colonial actors are presented as dynamic and complex causes of historical change, rather than simply evidence of diverse points of view.71 Many teachers stressed the notion of divided sentiment (loyalists versus patriots) as an indicator of the conflict’s uncertain outcome.72 Asking whether the revolution was avoidable or how the Constitution’s many compromises were generated, as a number of lessons do, pulls students above the fray to see how differing points of view actually propelled conflict, why chronology matters, and pushes them to contemplate how things might have turned out differently.73

A variety of activities ask students to put themselves in the position of a colonist or a British official at various stages of the conflict: investigating the crime scene at the Boston Massacre; judging the strategic wisdom of the Boston Tea Party; assessing the arguments of loyalists and patriots; deciding whether to quit or persevere at Valley Forge; reenacting the Constitutional Convention debates over the Great Compromise.74 Role-playing lessons have become more and more sophisticated, aided by video-gamified platforms and an expansion of roles beyond binary choices (loyalist versus patriot; Federalist versus Antifederalist). One newer unit on the revolution divides the question of independence into three options—loyalty, neutrality, or rebellion—and then further disambiguates each position with sources from colonists, Native people, and enslaved and free Black people. Rather than render a single judgment, students are assigned distinct historical roles—such as a Quaker merchant, an immigrant barmaid, a frontier farmer, an enslaved teenager, or a female Wampanoag sachem—with the expectation that each will come to a distinct conclusion about the conflict.75 In another widely used unit, a gamified version of the ratification debates puts students in the role of a pamphleteer who, on the basis of interviews with various social types from across the newly independent states, must make a case either for or against the Constitution.76 These approaches offer advantages: an emphasis on the social geography of colonial and postrevolutionary societies; a sense of the distinct material and intellectual problems that Independence and the Constitution were proposing to solve; and the notion that the outcome was “far from certain.”77 But a full immersion in inclusive role-playing scenarios may blur the real distinctions of status, power, and leverage that distinct social groups wielded during the 18th century. A sense of the real events may be tough to discern after a student has chosen their own adventure. From what we can infer about actual teacher practice, these are likely minor concerns; teachers deploy role-play as a supplement, not a substitute, for direct instruction about the course of events.

A few lessons address historical interpretation and introduce students to historiographic debates. Sometimes, debates are framed too bluntly, as in a side-by-side (and perhaps unfair) choice between Howard Zinn and Bernard Bailyn.78 Elsewhere, as in an inquiry task that asks students to assess the radicalism of the American Revolution, a spread of historiographic positions is summarized—but the scholarship referenced ends in the 1990s.79 More common than historiographic engagement were surveyed teachers’ many references to a set of “myths” that they suspected their students may have absorbed in elementary school or by way of “marble statues” that freeze the founders in civic memory. In broad strokes, surveyed teachers expressed a commitment to nuance and complexity, reminding students that the revolution resists a “good guys versus bad guys” plot, and that an appreciation for the great leaders and great achievements of republicanism requires a sense of what now might appear “flawed” and “imperfect.”80 Mythbusting, however, often requires teachers to cover the myth in order to refute it. A worthy ambition in one Washington unit to “tell untold stories” of the revolution relies on portraying the 1975 cartoon Schoolhouse Rock as if it were still a “commonly told” version of the founding.81 A unit in a large Illinois district extends critical postures into blunt abstractions, setting the revolution and early republic under an umbrella of “Power, Privilege, and Oppression.”82 The unit exemplifies the tensions between “critical” and “inclusive” histories; the names of ordinary and marginal people earn mention while revolutionary leaders are disappeared into “systems of power.”83

Notwithstanding the many incentives to diversify and complicate traditional versions of the founding, many teachers clearly find the high drama of elite politics an irresistible part of teaching the subject. Several positively referenced the popularity of the Broadway musical, enjoying “an excuse to watch Hamilton in class.”84 A Hamilton versus Jefferson framing of the politics of the early republic provides a durable framework for lessons. Combined with document-based role-playing activities, these are fine opportunities for students to historicize and dramatize the decision-making that drove important events. It’s also clear that teachers and curricular developers are eager to lend that same sense of drama to the disruptions and decisions that nonelites faced during the revolutionary moment. In recent decades, historical scholarship has greatly expanded the revolutionary narrative to include a wide range of participants, a heightened appreciation for the contingency of the imperial crisis, a transnational Atlantic milieu, the disruptions and transformations to land and labor, the consequences for pro- and antislavery politics, a prominent role for Native Americans, and analyses of gender, environment, consumer culture, print culture, and honor culture, to name just a few topics.85

The need to present the revolution’s legacy as a balancing act between achievements and flaws suggests a strong urge to draw lessons and legacies from the founding era across longer spans of time. Here, some ideological inflections were apparent. In one subset were teachers who stressed the founding as inspiration, an exemplary story of bravery and unity among underdogs who bore great risks and awful costs to stand against tyranny. For these teachers, the revolution imparts a clear lesson (echoed in teacher responses about the Civil Rights Movement) that Americans must continue to be protective of their rights and “stand up for themselves” against oppression.86 Another group of teachers hoped that students would remember the revolution’s limitations: that American notions of liberty, equality, and rights were neither imagined for nor enjoyed by people who were not “rich white landowners.”87 Other teachers referenced the participation (rather than the exclusion) of nonelites (slaves, women, servants, farmers), making some version of the case that the revolution “was fought by everyone.”88 One Virginia teacher split the difference between pluralism and pessimism, explaining, “women and African Americans made significant contributions but did not benefit from the revolution in the same way that white men did.”89 The most common ideological synthesis among teachers described the founding as an expansive and unfinished struggle—a combination of teachers’ historical sense of the American Revolution’s unexpected outcome and narrow social origins with their civic faith in democracy and equality. As an Illinois teacher summed up, “it’s a work in progress.”90

Westward Expansion

John Gast’s painting American Progress is one of the most assigned sources for students studying westward expansion. It appears everywhere from textbooks to document activities and teacher slideshows. Its title and its depictions of light and darkness, Native Americans, buffalo, wagons, trains, settlers, waterways, and the female figure of Columbia leading the way allow students to question the assumptions behind its 1872 creation and explore the stories that 19th-century Americans told about their migration and settlement in the trans-Mississippi West.91 But the painting is also a handy symbol for the overemphasis on the concept of Manifest Destiny that predominates in K–12 materials.92 Some teachers acknowledge, as much recent historiography stresses, the contingency of how westward expansion occurred “in stages for various reasons.”93 Perhaps only a handful of teachers today present westward expansion as “inevitable,” but a certain tragic fatalism about the history of the West still prevails.94 As one teacher put it, “The country had to grow, but unfortunately at the expense of Native Americans.”95 Maps of 19th-century territorial acquisitions and dates are a standard visual reference in most textbooks, necessary context that nonetheless can reinforce a deterministic sense of westward expansion. Some teachers and instructional materials have made conscious efforts to avoid this trap, moving beyond the broad outline to root these processes in local stories that do not require an emphasis on Manifest Destiny for students to understand this history.

Many teachers present westward expansion as a mixed bag of “pros and cons” or “good and bad” changes, leaving it up to students to draw their own conclusions about its meaning. A few place significant emphasis on character, telling students that “explorers and settlers were determined and resilient” with “grit,” while still noting “the costs.”96 Meanwhile, a different subset of teachers focus on what they see as the injustices of the era, in some cases using academic terms like “settler colonialism” to emphasize systemic and ideological continuities across broader time spans and geographies.97 These teachers may point to the ongoing rationale for later imperialist ventures beyond North America as a key to the present, fueling “our belief in American exceptionalism and nationalistic pride.”98

Some events most commonly included in this unit are the Louisiana Purchase, the Mexican American War, the Mormon migration to Utah, discoveries of gold, and the Homestead Act. Teachers also cover developing technologies in the form of canals, steamboats, railroads, and telegraphs that accelerated expansion and altered concepts of time and space.99 Though much of westward expansion takes place before the Civil War, topics such as the Homestead Act and railroads carry into and past 1865. This can make coverage of the topic into the 1860s and early 1870s challenging, given most teachers focus on the Civil War and Reconstruction in those decades. This break in the focus on westward expansion is further reinforced by the fact that most first-half and second-half US history courses end and begin in 1877–a break that can last several years between middle and high school coursework.

Surveyed teachers want to ensure their students understand the West was “not just barren land,” even if they lack the time to delve into Indigenous history.100 Indian removal, specifically the Trail of Tears, frequently is taught in this era but often disconnected from the broader story of westward expansion.101 Rarely do standards or curriculum give much detail about the dozens of distinct efforts undertaken by Native tribes to resist or determine the path of their removal. And seldom does the curriculum tie the removal of Indians to other antebellum events, including the expansion of slavery.102 A significant number of teachers connect westward expansion to slavery and the Civil War, but the common organization of units with titles such as “Road to the Civil War” makes it likely that Native removal will be told as a tragic standalone, while events such as the Missouri Compromise are swept into forward motion as a preface to the war.103 Connecting removal, slavery, and sectionalism—as New York’s standards gesture toward—is the exception rather than the rule.104

While many lesson plans continue to present westward expansion as white people dispossessing Native peoples of their lands, a growing number of resources present the West as a more dynamic and diverse place, especially after the Civil War.105 Teachers and content providers emphasize the region’s diverse communities to push against “classic Hollywood stereotypes” of white, loner cowboys.106 Even within the broader outline of this core conflict, some teachers present the topic “not merely a simple one vs. one event but rather a multi-decade long series of conflicts between settlers, state militias, federal military, and numerous tribes.”107 In many cases, lessons try to incorporate as many identities as possible, including women, Chinese, and African Americans, to answer broader questions about the range of actors and how they are described.108 While Rhode Island’s standards describe westward expansion as the “westward movement of white Americans,” other approaches address immigration as an important part of the story of how Americans moved west.109 This is also the topic in which teachers are most likely to discuss the history of the environment, including how western landscapes were shaped and altered in this process. For example, one Texas district curriculum asks, “How did westward expansion affect the landscape and people that interacted with it?”110

A local approach to westward expansion helps to ground this vast history in specific and relevant details; this is true even in places outside the West. For example, New York state standards make connections between the history of the Erie Canal and westward expansion.111 Michigan’s standards bring in the Treaty of Chicago and the Treaty of Fort Wayne.112 In Colorado, they explore the state’s gold rush.113 Many states in the West and Midwest credit railroads as the central engine for development, and this is reflected in their lessons.114 A Colorado lesson allows students to explore Denver’s development through city and railroad maps of the surrounding region.115 One Washington teacher noted the relevance of place, writing, “As I live and teach in the West and my school is named to honor a local native chief, the effects of Westward Expansion on the native cultures is always embedded in this topic.”116 National curriculum providers also present in-depth histories of specific places, Native nations, and conflicts while connecting these to themes such as “cultural misunderstanding, adaptation, cooperation, and conflict.”117

On the other hand, some curriculum plans indicate overly general questions and descriptions that give students the wrong impression about the significance of westward expansion. A lesson from one Texas district reads, “Migration of large numbers of people tend to create big changes.” The map paired with the lesson goes on to define westward expansion as an inevitable process: “Manifest Destiny led to the settlement of the West and the expansion of American territory to the Pacific Ocean by 1850.”118 More commonly, teachers impose Manifest Destiny as the explanation for all of westward expansion in a way that extends beyond the events that actually occurred.119 Some lesson plans take immigration and “urban crowding” as an inevitable force for westward expansion.120 Role playing activities, such as a “Land Run Simulation” regularly with this topic, may give students the wrong impression about westward expansion as a process without costs or allow stereotypes to fill in the gaps.121 The varied religious, sectional, national, and economic goals that contributed to westward expansion—and the role of Native people in shaping and stalling its dynamics—do not always get the full attention of teachers and students. A close reading of Gast’s American Progress is a fine start, but many teachers would be excited to learn how historians of the West now paint a different picture without Manifest Destiny as the core concept.

Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction

The Civil War is a popular topic among teachers, with 30 percent of surveyed teachers choosing it as their favorite—the fourth highest ranked among all eras.122 Based on our interviews, surveys, and curricula appraisals, there no longer appears to be any serious controversy among teachers about slavery’s central role as the cause of the Civil War.123 Virtually all teachers we surveyed are teaching their students that the Civil War was “about slavery,” as one respondent put it.124 Perceiving that students arrive to the study of slavery with pre-existing assumptions (such as the Lost Cause mythology), teachers pointedly call out these misconceptions. For example, in a classroom activity used in a large Texas district, students look at 2011 polling data showing widespread public opinion that states’ rights, rather than slavery, was the main cause of the war. Students are asked to compare those results with what they’ve learned and to discuss how these responses might have changed in recent years.125 The signals are clear: teachers expect students to know that slavery was the core issue of the Civil War. Of surveyed teachers, 71 percent listed slavery and the antebellum South as a high-priority topic.126

Yet slavery still could be covered more comprehensively. Slavery was singled out by teachers as a uniquely challenging topic due to its potential for controversy. In our survey, 21 percent of teachers reported that slavery was challenging to teach, peaking at 29 percent in Iowa and Pennsylvania.127 When asked why, 43 percent of those teachers said it provokes conflict, a much higher percentage than any other content area in our survey. This latter statistic sets slavery even further apart from other challenging topics, where teachers pointed instead to time constraints, lack of training, or lack of student interest as the major hurdles.128 For teachers who said they had personally experienced objections to anything they taught, slavery was by far the leading specified topic of controversy.129 The pressure that teachers perceive regarding the teaching of slavery can come from a number of directions: conservatives claiming that slavery is divisive, students disengaging because they feel that it’s been done too much, or parents preferring that African American history emphasize postemancipation triumphs over the sorrows of slavery.130

Unlike most other content areas that can be more neatly periodized (e.g., Jacksonian America, the Civil War, the New Deal), slavery coexists with the entirety of the first half of US history. Even so, curricular coverage of slavery clusters around particular historical moments, especially constitutional debates and plantation slavery in the antebellum South, the latter often standing in for the various practices and cultures of slavery that existed throughout the United States before 1865. In most curricula, these eras are presented primarily as a political story: rising tensions, diverging economies, competing interpretations of the Constitution, and an increasing sense of morality. In the classroom, characters like Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, Harriett Beecher Stowe, William Lloyd Garrison, or Robert E. Lee typically drive the story. Students read core documents such as Douglass’s 1852 “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” and Lincoln’s 1858 acceptance speech for the Republican nomination.131 Common events include the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Compromise of 1850, and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. During the war itself, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, and the surrender at Appomattox are presented as the key turning points and events to understand.

Beyond Douglass, the rich historiography regarding free and enslaved Black people’s role in abolition rarely appears.132 Students often learn about ordinary Black freedmen from a classroom viewing of the 1989 film Glory.133 Likewise, evidence of what slavery was like and how it changed appears in some cases but is usually limited.134 Textbooks generally include information about the daily lives of enslaved people, though perhaps in recognition of the younger audience, they skirt important violent aspects such as sexual assault. The textbooks we appraised had a separate chapter section dedicated to social life under slavery.135 In modular primary source lessons, however, students are more likely to learn about slavery by examining runaway slave advertisements. These sources document the cruelty of enslavement without much sense of the interior lives and desires of the enslaved.

The study of Reconstruction usually occurs at the end of the first half of the US history course, which could come at the end of a semester or school year, depending on state and local course sequencing. This is a logical placement, but it relies on strict pacing to ensure enough time to study the topic. Indeed, 62 percent of teachers who described teaching Reconstruction as challenging listed time constraints as the reason. Many teachers present both the “successes and failures” but tend to focus more on the “challenges and failures of Reconstruction policies.”136 As one Pennsylvania teacher put it, “We started a path of change but quit when it was getting hard.”137 Students learn not only about the federal government’s role but are frequently asked, “How did African Americans work to improve their lives in Reconstruction?”138

In most locales, students are more likely to learn about the daily lives of African Americans during the study of Reconstruction than the Civil War or antebellum era. For example, a common question asks the extent to which the lives of formerly enslaved persons improved after the war. To respond students must first answer “What were the conditions of slavery before the Civil War?”139 Students consistently learn about the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments in a Reconstruction unit. The expansion of the federal government in this period is not always explicitly covered, as the spotlight instead falls on the federal government’s failure to protect the lives and rights of freedpeople from racist violence and Redeemer state governments. Rarely do teachers describe why the will to enforce the nation’s laws foundered; there are not individual agents of change in this era so much as a generic sense of “government.” In both the Civil War and Reconstruction units, teachers point to these eras’ lasting consequences and legacy that connects to the present, with Reconstruction often described as unfinished.140

Despite the national story, local variation and focus provide some of the most engaging lessons that go deeper than the dichotomies of North and South and black and white. Louisiana’s state standards include a study of “the experiences of enslaved people on the Middle Passage, at slave auctions, and on plantations,” as well as the inclusion of the “capture of New Orleans” as a major Civil War battle. In the West, students are more likely to learn about the expansion of the federal government, connecting it to conflicts with Native peoples. Rhode Island’s state standards provide evidence of Black people’s involvement in the war with the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. The state also has one of the few standards with any mention of women in relation to the Civil War.141

Though teachers and curriculum writers understand and convey the broad political outline of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction, there are plenty of moments of misinterpretation. Rarely do curriculum documents reflect on how slavery and racism were mutually constructed and how both changed over time and place.142 White supremacy appears in some histories as a constant, unchanging feature, as opposed to a politically contingent and historically constructed phenomenon.143 In some cases, moralistic simplifications for the origins of slavery stand in for a rich historiographic debate, reflecting ahistorical emphases similar to those we found in some Native American history lessons.144 A unit in one Connecticut district was designed to treat slavery with depth and emotional resonance, but it ends up flattening the origins of racial slavery in the early modern Atlantic world by using a simplified account of “the world’s first racist” in the Portuguese royal court.145 Elsewhere, the urge to connect slavery to racism’s longer arc in American life encourages imprecise and disorienting analogies. A Pennsylvania unit invites students to interpret a viral birdwatching incident in Manhattan in 2020 with reference to slave laws passed in the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion in colonial Virginia.146 In contrast, material that engages with recent debates about contextualizing or removing Civil War monuments that celebrated the Confederacy are often more nuanced, sometimes even grounded in the district’s own history.147 In dispelling “myths” about slavery, another lesson plan wants students to know that slaveowners did not own slaves “just to be mean.”148 While the premise sounds flippant, such a prompt can be generative as a pivot to explore the matrix of economic motives that sustained slavery. Pure economism has its limits as well; while no teachers we spoke to or surveyed apologize for slavery in their courses, their efforts to explain the economic existence of slavery sometimes give it a sense of inevitability that should not be applied to either its existence or its end. Along these lines, curriculum and textbooks consistently overemphasize the importance of Eli Whitney and his cotton gin to the spread of plantation slavery.149 The curriculum furthest afield came from an Alabama district that described Reconstruction as the era when “mercy turn[ed] to vengeance,” as the North left the South “humiliated and desperate.”150 Few teachers seem to have an appropriate understanding of sharecropping, calling it among other things “a legal form of slavery,” missing the significance of emancipation. Often the topic of sharecropping is most clearly and accurately presented in textbooks that note its negotiation and explain the range of labor systems including sharecropping, share-tenancy, and tenant farming.151

Finally, a sizable minority of teachers spend excessive time in the Civil War era discussing military history, going beyond the key turning points to discuss upwards of 20 battles.152 Crash Course even recorded an episode where they “just list some facts” about battles to address teachers’ requests.153 For some teachers, the military conduct of the war is clearly a topic of personal interest—a passion that sends them to reenactments on weekends and battlefield sites over the summer.154 While these hobbies can translate to interesting field trips and artifact show-and-tells, an excessive focus on military history leaves out far too much of the other histories that students should learn about. Rarely do these battle histories explore how enslaved people freeing themselves by running to the US Army, the enlistment of freedmen, and the Emancipation Proclamation were tied to both the military necessities of the war and the process of emancipation.155 Taken together, instructional treatments of the Civil War and Reconstruction are roughly in line with scholarly interpretations of the era’s political history, but the insights of social and economic history could stand to be more coherently incorporated.

Industry, Capital, and Labor

The most thematic of the six appraised content areas, “Industry, Capital, and Labor” crosses the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. Commonly grouped under the umbrella of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, these themes capture the emerging industrialized economy as it radically transformed the United States and American life.156 Every shift within the economy created both grievances and opportunities. Technology surged, capital accumulated, workers organized, and a class of educated bourgeois reformers tried to dam up the resulting tensions. The many framings of this era as “the making of modern America” underscore the sense among some that the turn of the 20th century is an origin story for the second half of the US survey.157

Teaching the scale of economic change after Reconstruction alone is daunting, and teachers report struggling to make it digestible. Of the 19 percent (301) of respondents who deemed the Gilded Age and Industrial America one of the three most challenging topics to teach, 66 percent further clarified that they find students too uninterested, disengaged, or academically unprepared.158 Teachers frequently commented that students struggle to keep up, agreeing with one teacher who acknowledged that the era is full of “so many themes and forces that overlap” that “it can be difficult to have depth and to provide conceptual understanding, without going on and on and on.”159 Another teacher responded, “There are so many threads to tie together in this time period—westward expansion, Native Americans, industrialization, immigration, fallout from Reconstruction. It’s a lot for the kids to track.”160 Some reported feeling pressure to streamline the “slog,” as a Virginia teacher put it: “I either have to leave a lot out or just pretend everyone is still excited.”161 The Progressive Era yielded similar results, which is unsurprising given that it is most often positioned in curricula as a direct response to Gilded Age conditions.162 Teachers made a case for its relevance to students’ lives while simultaneously expressing frustration that they cannot make their students connect to the material. A Texas teacher complained, “A lot of the changes/reforms during this era have been around for 100+ years so [the students] think it is obvious.”163 Given these obstacles, it is no surprise that most Gilded Age and Progressive Era curricula approach the eras by streamlining lesson plans, simplifying coverage, and outsourcing subject matter to documentaries that teachers can manage and students can tolerate.

Teacher sentiment perhaps can be traced to the uneven treatment of the Gilded Age in the K–12 US history sequence. Roughly half of high school US history state standards suggest or require a second-half US history course (the only US history course that the vast majority of high school students must take), usually beginning after Reconstruction in 1877. As the Gilded Age is generally covered in the first month of the semester, often at least three years after students took their last US history class (and with a new-to-them history teacher to boot), it is a difficult task for students to enter the door capable of engaging with the “complex mix of groups, ideas, and agendas that all melt into a ‘soup’ of movements throughout the early 20th century.”164 Across interviews, teachers spoke of the shaky transitions between middle school and high school history classes. The Gilded Age would, of all subject areas, be the rubric content area most disadvantaged by the scope and sequence structure that constitutes something of a consensus in the United States. Even where there is a mandate for coverage of the Gilded Age, external factors can inflect the seriousness with which it is taught. As one Virginia teacher wrote, “Virginia’s [Standards of Learning] requirements/state test do not really push a lot in this area . . . so I do not stress much of it in class.”165

Despite evidence of different historiographic strains in Gilded Age and Progressive Era curricula, lessons rarely align entirely with any orthodoxy. One strain is the exploration of “modernity,” a present-focused approach whereby teachers offer a collection of sometimes connected, sometimes stochastic events designed to add up to something that students can recognize in today’s United States. This emphasis is front and center in course and unit titles like the “Beginning of Modern America”’ or the “Emergence of Modern America.”166 What “modernity” means is never defined, but its curricular starting line in the Gilded Age communicates a thesis: to understand the United States today, one must understand the history of accumulation—of money, people, land, resources, influence, and, as teachers often emphasize, social problems.167 The accumulation of capital, in particular, is linked with the rapidly multiplying ills of Gilded Age society, whether through wealth inequality or the rise of philanthropy, both of which are covered fairly well among collected curricula. While the corporate monopoly and its mechanisms, like vertical and horizontal integration, are standard fare, materials generally avoid deeper discussion of economics or even more developed histories of blockbuster businesses like Standard Oil or J. P. Morgan and Co., while the men behind them, like John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, appear on the scene already wealthy and influential.

Even as Gilded Age titans appear in curricula as historical forces in themselves, no one seems content to let them off the hook. Instances of soft-pedaling or skipping over some of the more disreputable actions of Gilded Age tycoons are rare. The historically acceptable but nonetheless pejorative term “robber baron” appears frequently. A few teachers note that rationalizations for wealth inequality rested on social Darwinism.168 Curricula that lean into “haves” and “have-nots” framing are more likely to present one or more of a host of similarly simplified dichotomies—of “good and bad,” “winners and losers,” “positive and negative,” “better and worse”—all of which highlight the inextricable ties between capitalist accumulation and the historical evolution of more sociological or political conceptions of inequality and progress.169 As five respondents said and others paraphrased, “All that glitters is not gold.”170 One particularly awkward question—“Which term best describes Andrew Carnegie? Philanthropist or Robber Baron?”—highlights how curricula lean into moral questions about the Gilded Age.171 In these depictions, the Progressive Era is an attempt to solve the problems of the Gilded Age, often creating more problems of its own through its middle-class standards and embrace of social Darwinism, among other ideologies.172

In a complementary framing, the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era are presented with a more sociological approach, populated by masses, systems, and ideologies. These concepts are either distilled into keywords or used as actors to drive much of the era’s “plot.” These clusters of concepts often appear with lists of nominalized verbs and adjectives: “Industry, Reform, and the West”; “Industry/Cities/Progressives/Immigration”; and “Industrialization, Progressivism, and Immigration.”173 Framing the era through these broad concepts suggests that to understand the United States today, one must understand how the masses, through mass movement, mass politics, mass protest, mass organization, mass demographics, altered and vied for power within the American social contract.174

This sociological approach can effectively convey the scale of the Gilded Age. But it is employed with varying amounts of rigor, ranging from a simplified, sociology “lite” to a deeper, more disciplined use of sociological tools in historical analysis.175 On the more prevalent simplified side of the spectrum, keywords from both the Gilded Age and Progressive Era form a barrier of anonymity that only the most well-known and elite historical actors, like Carnegie and Rockefeller, can breach. Arizona’s recommended “course considerations” are representative here, suggesting coverage of the “emergence of Modern America including but not limited to industrialization, immigration and migration, progressivism, Federal Indian Policy, suffrage movements, racial, religious and class conflict, the growth of the United States as a global power and World War I and its aftermath.”176 Lessons using the simplified approach certainly appear more scientific, with rapid-fire statistics and myriad graphs of varying quality, but agency among the masses is largely missing, as are connections between new immigration, unsafe workplaces, and child labor, particularly within the labor movement. More so than any other moment in US history except perhaps the invention of the cotton gin, many lessons lean into the idea of technology shaping and often “improving” daily life in this era.177

A small but exemplary number of standards and curricula present industry, capital, and labor as inextricably intertwined with and in reaction to one another and historical conditions. Mississippi’s standards juxtapose these concepts and require students to understand the interaction between big concepts and individuals. Under “Industrialization,” students compare “population changes caused by industrialization,” “the nativist reaction evidenced by the Chinese Exclusion Act,” “the impact of industrialization on workers,” “living conditions linked to urbanization,” the “social gospel,” Jane Addams, and the rise of labor unions.178 Teachers find ways to frame the complexity of the era through case studies of representative figures (e.g., Andrew Carnegie) or local history (e.g., the spread of technology and its hastening of migration in the post–Civil War West, or the “Silver Kings of Colorado”).179 As in other content areas, some of the most helpful lessons are grounded in state and local history, asking students to consider nearby industrial sites, which may or may not still be in operation.180 In one Connecticut district’s case study on the labor movement, students examine the labor context of the Gilded Age and ask “what caused the development of labor unions,” “what issues did labor organizations seek to address and what methods/tactics did they utilize,” “how did industry attempt to deter organized labor,” and “to what degree did labor unions succeed in their goals during the Gilded Age?”181 Other districts add texture to the labor movement, either by requiring students to “analyze the causes and effects of labor conflict in various industries and geographic regions” or learn about the “growth of labor unions and various radical movement which experienced various degrees of success in achieving their goals,” including anarchism, socialism, the American Federation of Labor, and the Industrial Workers of the World among labor’s diverse camps.182

Despite evidence that some teachers embrace the breadth of the early eras and iterations of the labor movement, the plurality of appraised materials are anemic on labor history, particularly prior to the New Deal expansion of labor laws. Important events like the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire are included in many US history curricula, but time is rarely taken to explore labor radicalism in New York City or the complex urban politics within which the event occurred. Labeling labor unions as just another reform movement in a roiling sea of reform movements, and as a consequence of a middle-class movement for reform, rather than a complex, multifaceted, and politically diverse movement with its own dramatic narratives and consequences, does not help explain the historical highs and nadirs of workers’ rights in the United States. Teaching the labor movement as another domain of a bourgeois reform movement alongside Upton Sinclair and Theodore Roosevelt not only ignores its early history (e.g., brotherhoods, trade unionism) but cleaves it from its dramatic ascendance during the New Deal. In Pennsylvania, one district provided a packet of primary sources on the Gilded Age and reform efforts, going in-depth on capital, reform, and regulation. In 58 pages, labor unions are mentioned only in passing in sections on social Darwinism and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.183 On the other hand, some curricula ask questions such as “To what extent were lower class and working Americans left behind during the Progressive Era?”184 And some textbooks have entire sections focused on the range of labor unions.185

Despite relying more on a thematic approach than the five other appraised content areas, several key themes rarely appeared in appraised curricula, reflecting the choices teachers and curriculum providers make to avoid overwhelming students. For instance, international context for the era is rare, an unfortunate fact for the age in which the United States developed a truly global economy. Historians recognize that the era of industrialization was a global age, not just an American one, but curricular materials rarely mention other countries unless as part of a military contest. The global context for 19th-century imperialism is often left to world history classes, and the global origins of financial panics go unmentioned. Women are more likely to appear in coverage of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era than in preceding units, but a focus on the achievement of suffrage in 1920 tends to overshadow the diverse extent of women’s movements across the 19th and early 20th centuries. Even when important themes like imperialism, immigration, environment, and labor appear, the causal links between them are often left unexplored.186 Immigrants are pulled to the United States, but what pushes them, beyond the rare mention of famine or war, is underemphasized. The environment and Americans’ concerns about environmental changes receive scant attention. Given how Americans’ relationship with the natural world transformed in this era, and that economic growth was fueled not simply by technology and ideology but by fossil fuels, these intersections seem particularly relevant to understanding modern America and the modern world.

The Civil Rights Movement

Two aspects set the Civil Rights Movement apart from other content areas under appraisal. The Civil Rights Movement is the only content area that can be critiqued by still-living participants and witnesses. Relatedly, coverage of the Civil Rights Movement enjoys robust and widespread support, as demonstrated across social studies standards, state law, and teacher priorities. The movement’s status as living history, civic monument, and historical turning point has put substantial pressure on all levels of public education bureaucracy to encourage curricular coverage.187 Surveyed teachers ranked the Civil Rights Movement as the clear standout for priority coverage, with 81 percent identifying the topic as a “high priority.” Including those who chose “mid-priority,” the number rises to 94 percent, as close as teachers came to a unanimous statement regarding any survey question. In Alabama, where the topic’s local significance is unavoidable, the number actually reached 100 percent. Among favorites, the Civil Rights Movement ranked third with 36 percent, trailing only the founding era and World War II. Teachers in Washington and Alabama registered the highest affinity for the civil rights movement, with 47 percent and 44 percent, respectively, citing the topic among their favorites to teach. In state standards with specified historical content, the Civil Rights Movement never fails to make an appearance, and state legislatures have issued multiple signals about the era’s importance to civic knowledge.