From GI Roundtable 2: What Is Propaganda? (1944)

The fact that wars give rise to intensive propaganda campaigns has made many persons suppose that propaganda is something new and modern. The word itself came into common use in this country as late as 1914, when World War I began. The truth is, however, that propaganda is not new and modern. Nobody would make the mistake of assuming that it is new if, from early times, efforts to mobilize attitudes and opinions had actually been called “propaganda.” The battle for men’s minds is as old as human history.

In the ancient Asiatic civilization preceding the rise of Athens as a great center of human culture, the masses of the people lived under despotisms and there were no channels or methods for them to use in formulating or making known their feelings and wishes as a group. In Athens, however, the Greeks who made up the citizen class were conscious of their interests as a group and were well informed on the problems and affairs of the city-state to which they belonged. Differences on religious and political matters gave rise to propaganda and counterpropaganda. The strong-minded Athenians, though lacking such tools as the newspaper, the radio, and the movies, could use other powerful engines of propaganda to mold attitudes and opinions. The Greeks had games, the theater, the assembly, the law courts, and religious festivals, and these gave opportunity for propagandizing ideas and beliefs. The Greek playwrights made use of the drama for their political, social, and moral teachings. Another effective instrument for putting forward points of view was oratory, in which the Greeks excelled. And though there were no printing presses, handwritten books were circulated in the Greek world in efforts to shape and control the opinions of men.

From that time forward, whenever any society had common knowledge and a sense of common interests, it made use of propaganda. And as early as the sixteenth century nations used methods that were somewhat like those of modern propaganda. In the days of the Spanish Armada (1588), both Philip II of Spain and Queen Elizabeth of England organized propaganda in a quite modern way.

On one occasion, some years after the Spanish Armada, Sir Walter Raleigh complained bitterly about the Spanish propaganda (though he didn’t use that name). He was angry about a Spanish report of a sea battle near the Azores between the British ship Revenge and the ships of the Spanish king. He said it was “no marvel that the Spaniard should seek by false and slanderous pamphlets, advisoes, and letters, to cover their own loss and to derogate from others their own honours, especially in this fight being performed far off.” And then he recalled that back at the time of the Spanish Armada, when the Spaniards “purposed the invasion” of England, they published “in sundry languages, in print, great victories in words, which they pleaded to have obtained against this realm; and spread the same in a most false sort over all parts of France, Italy, and elsewhere.” The truth of course was that the Spanish Armada suffered a colossal disaster in 1588.

The Spanish claims, though described in the language of Queen Elizabeth’s time, have a curiously modern ring. Make a few changes in them, here and there, and they sound like a 1944 bulletin from the Japanese propaganda office.

The term “propaganda” apparently first came into common use in Europe as a result of the missionary activities of the Catholic church. In 1622 Pope Gregory XV created in Rome the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. This was a commission of cardinals charged with spreading the faith and regulating church affairs in heathen lands. A College of Propaganda was set up under Pope Urban VIII to train priests for the missions.

In its origins “propaganda” is an ancient and honorable word. Religious activities which were associated with propaganda commanded the respectful attention of mankind. It was in later times that the word came to have a selfish, dishonest, or subversive association.

Throughout the Middle Ages and in the later historic periods down to modern times, there has been propaganda. No people has been without it. The conflict between kings and Parliament in England was a historic struggle in which propaganda was involved. Propaganda was one of the weapons used in the movement for American independence, and it was used also in the French Revolution. The pens of Voltaire and Rousseau inflamed opposition to Bourbon rule in France, and during the revolution Danton and his fellows crystallized attitudes against the French king just as yarn Adams and Tom Paine had roused and organized opinion in the American Revolution.

World War I dramatized the power and triumphs of propaganda. And both fascism and communism in the postwar years were the centers of intense revolutionary propaganda. After capturing office, both fascists and communists sought to extend their power beyond their own national borders through the use of propaganda.

In our modern day, the inventive genius of man perfected a machinery of communication which, while speeding up and extending the influence of information and ideas, gave the propagandists a quick and efficient system for the spread of their appeals. This technical equipment can be used in the interests of peace and– international good will. Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo preferred to seize upon this magnificent nervous system for selfish ends and inhumane purposes, and thus enlarged the role of propaganda in today’s world. While the United Nations were slow at first to use the speedy and efficient devices of communication for propaganda purposes, they are now returning blow for blow.

The modern development of politics was another stimulus to propaganda. Propaganda as promotion is a necessary part of political campaigns in democracies. When political bosses controlled nominations, comparatively little promotion was needed before a candidate was named to run for office, but under the direct primary system the candidate seeking nomination must appeal to a voting constituency. And in the final election he must appeal to the voters for their verdict on his fitness for office and on the soundness of his platform. In other words, he must engage in promotion as a legitimate and necessary part of a political contest.

In democracies, political leaders in office must necessarily explain and justify their courses of action to an electorate. Through the use of persuasion, those in office seek to reconcile the demands of various groups in the community. Prime ministers, presidents, cabinet members, department heads, legislators, and other officeholders appeal to the citizens of community and nation in order to make a given line of policy widely understood and to seek popular acceptance of it.

In peacetime the promotional activities of democratic governments usually consist of making the citizens aware of the services offered by a given department and of developing popular support for the policies with which the department is concerned. The purpose is to make these services “come alive” to the everyday citizen, and in the long run official information and promotion tend to make the average man more conscious of his citizenship. If the public is interested in the work done in its name and in its behalf, intelligent public criticism of governmental services can be stimulated.

Recent economic changes have expanded the volume of propaganda. Under the conditions of mass production and mass consumption, techniques of propaganda and public relations have been greatly developed to help sell commodities and services and to engender good will among consumers, employees, other groups, and the public at large.

Related Resources

September 7, 2024

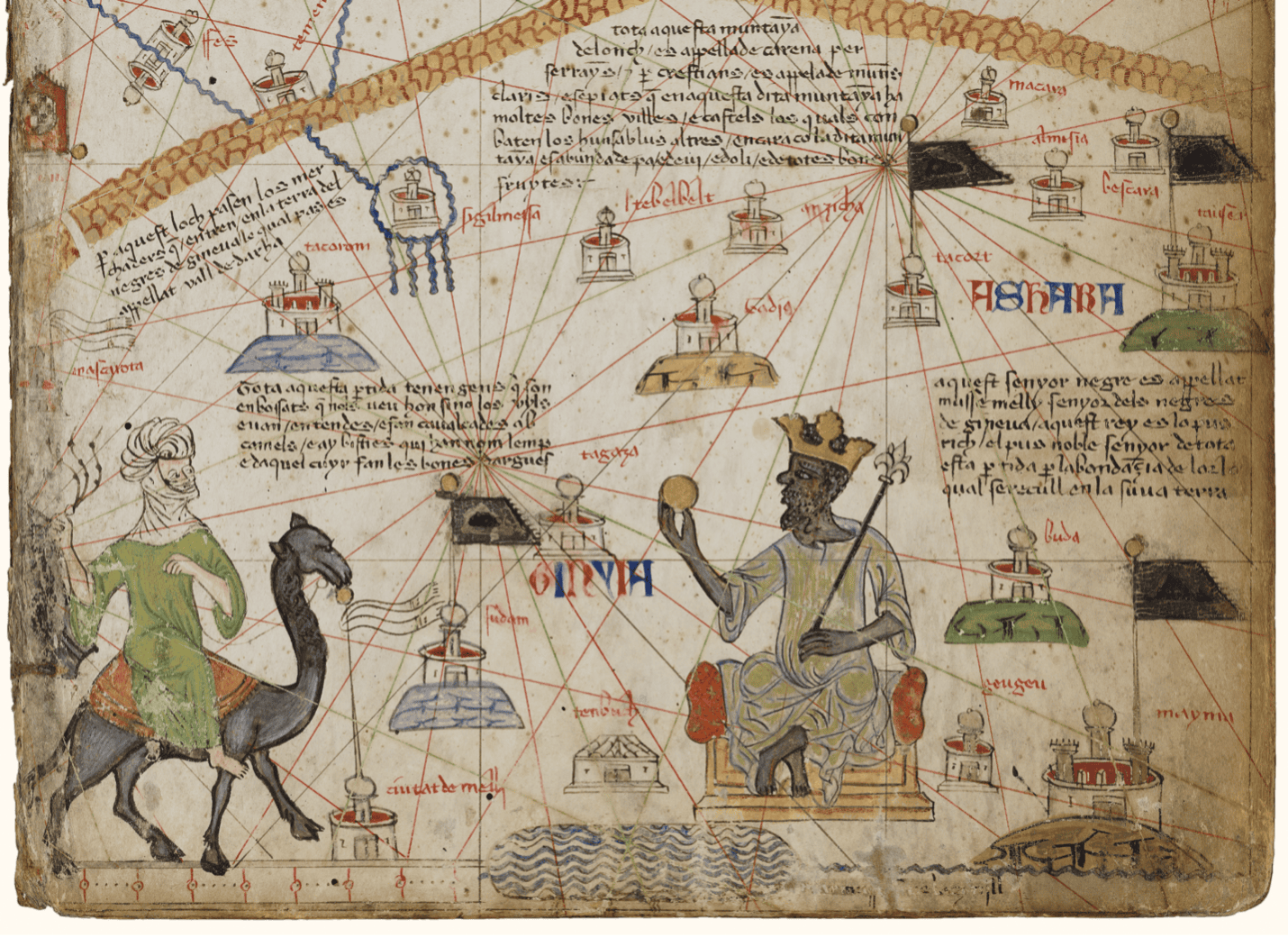

Travel and Trade in Later Medieval Africa

September 6, 2024

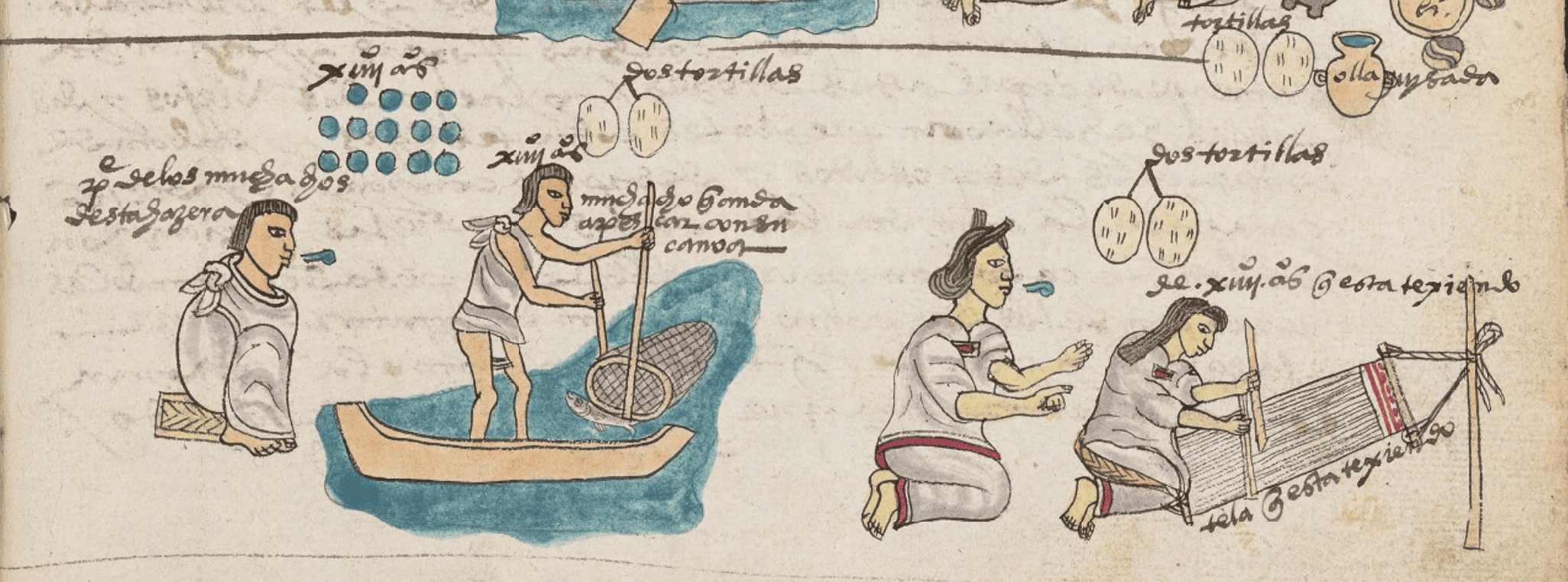

Sacred Cloth: Silk in Medieval Western Europe

September 5, 2024