This resource is part of the Silk Roads and Beyond: Trade, Exchange, and Travel in Ancient and Medieval Afro-Eurasia toolkit, from the AHA’s Teaching Things project.

Optional Materials

- Swatch of silk or silk garment(s) to allow students to tactilely interact with the woven silk material

Introduction

The Silk Roads networks facilitated the trade of countless types of goods over the wide-ranging geography of Afro-Eurasia, including (but not limited to) foodstuffs and spices, livestock and furs, ceramics, and jade. Nevertheless, textiles were an all-important commodity along these networks of exchange. In this lesson, students will consider women’s roles in Chinese silk production and Aztec textile production during the later medieval period. An optional lesson also prompts students to compare these examples with women’s work in modern industrialized textile production in the United States and Britain.

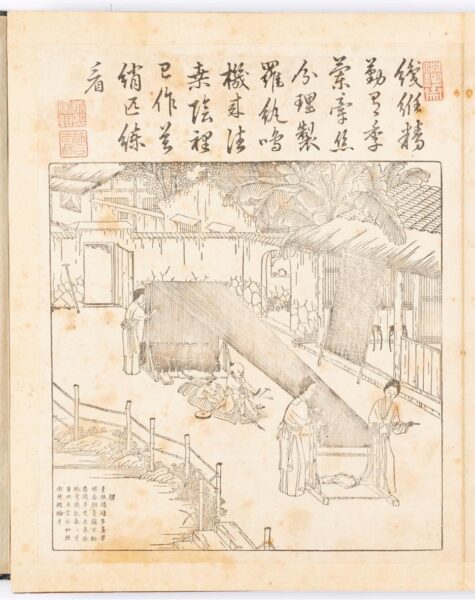

Students will be asked to write short responses to a series of questions about an image of Chinese silk production to demonstrate their understanding of this topic and ability to synthesize complex concepts. This short response is in the format of an AP stimulus-based Short-Answer Question, but can be used in non-AP high school and college classrooms.

Part I: Contexts

Watch this Silk Roads overview video from Heimler’s History (particularly useful for AP World History), (8:54 mins):

Watch this video about silk production in China by UNESCO, (9:35 mins):

Part II: Women’s Roles in Premodern and Early Modern Textile Production

Have students read Yue Li’s “The Content of Women’s Work” from her American University Art History Museum project titled Picturing Female Morality: “Illustrated Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety” and Women’s Social Life in Twelfth-Century China. Students should pay close attention to the images of gendered labor illustrated in the article.

Students should then read the following excerpts from Elizabeth M. Brumfiel’s, “Aztec Women: Capable Partners and Cosmic Enemies” (2008).1

Gender complementarity also emphasized the equivalence and interdependence of men and women in economic and social life. In Aztec households, men and women were assigned different duties with the understanding that both sets of activities were necessary for the success of the family. male activities generally occurred outside of the house: farming, fishing, long-distance trading, and making war. Female activities were mostly connected with the house and its courtyard: sweeping, cooking, and weaving. Interestingly, childcare was not considered a particularly female activity. Women were responsible for educating their daughters, and men were responsible for training their sons.

Men’s and women’s economic roles were marked at birth. In the ceremony for the newborn infant, a baby girl was presented with the implements for her future labor: a broom, a reed basket containing unspun fiber, a spindle for spinning thread, and a small bowl to support the spindle. Baby boys were also given the things that they would use as adults: the tools of a carpenter, a feather worker, a painter of books, or a goldsmith, or the shield and arrows of a warrior.

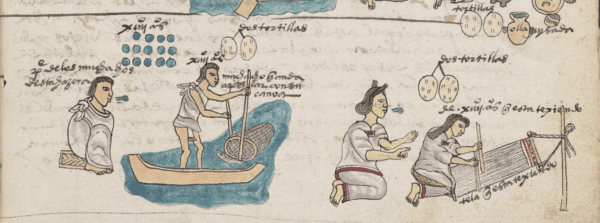

Finally, students should spend time analyzing this Aztec manuscript (the full digitized version can be found on the Digital Bodleian website).2 Educators should emphasize that while Aztec women were participating in textile production and weaving, they were not using silk but rather plant-based fibers.

Discussion Questions

- How might you define “feminine” today?

- Consider the perspective you bring to this discussion, such as your own personal views and lived experience. How does this affect the way that you might define this term?

- Does your definition change if you think about definitions for “feminine” across time and space (i.e. in the past, or in a place that is different from where you call home)?

- With all of this in mind, why do you think that textile production was historically considered “feminine” or women’s work?

- Compare and contrast the Chinese images of weaving and tilling from the website and the Aztec illustration of fishing and weaving from the manuscript excerpt.

- What do you learn about the physical aspects of textile labor for women? What kinds of materials and tools are required?

- How is Chinese sericulture labor different or the same as Aztec plant-based fiber textile production?

Part III: Activity

The following activity is based on the College Board Advanced Placement History exam model of short-answer questions (SAQs). This is meant to make this Object Lesson a useful resource for AP World History teachers and is easily integrated into non-AP history and college classrooms as well.

As an in-class or homework writing assignment, have students spend 15-20 minutes total answering the following prompts in 3-5 sentences each using the T.E.A. model:

- Topic sentence that succinctly answers the prompt

- Evidence that is specific

- Analysis that links the evidence to both the claim of the topic sentence as well as the “stimulus” (in this case, the image)

Scene from Imperially Composed Pictures of Tilling and Weaving 御製耕織圖 by Jiao Bingzhen 焦秉貞. Made in 1696 during the Qing Dynasty based on a genre of scroll paintings first created by Lou Shou 樓璹 (1090-1162) during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). (from Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Murray Warner Collection, MWCH51:C1)

- Describe at least one of the materials of sericulture necessary to produce the weave illustrated in the image.

- Describe one way in which this image uses objects and scenery to depict the role and expectations of women in Chinese society.

- Using a specific example from outside of China, explain how this image and its depiction of women connects to the history of women in textile work more broadly.

Part IV: Women’s Roles in Textile Production During the Industrial Revolution

The centrality of women in textile production was not unique to the premodern and early modern periods. A significant aspect of the Industrial Revolution in Europe and North America was the widespread introduction of women into the industrial workforce, and especially in textile factories.

Have students read Heather Lash’s “Allentown Silk in the Nineteenth Century: Reassertion of Gender Hierarchies,” a part of Muhlenberg College’s Senior Seminar in Anthropology project, Iron Lives: People of the 19th Century Iron Industry of the Lehigh Valley.

Discussion Questions

- How were women treated within the silk textile industry in Allentown, Pennsylvania?

- What is the “gender hierarchy” within this industry that Lash refers to?

Part V: Student Activity

The following activity is loosely based on the College Board Advanced Placement History exam model of long-essay questions (LEQ) but does not fit within 1 of the 3 chronological groupings of questions. This is meant to make this Object Lesson a useful practice resource for AP World History teachers and is easily integrated into non-AP history and college classrooms as well.

As an in-class or homework writing assignment, students should spend approximately 45 minutes answering the following prompt. The essay should:

- Contextualize the topic at hand

- Include a thesis statement

- Organize paragraphs around topic sentences and specific pieces of historical evidence

Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which textile production was seen as “women’s labor” in societies across the world from the 13th century to today.

Additional Teaching Resources

- For more on the genre of tilling and weaving images, see “Collecting “Pictures of Tilling & Weaving” in the digital exhibition, The Artful Fabric of Collecting, a collaboration between the University of Oregon Libraries and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art.

- For more on the relationship between textile production as “women’s work” and the slow move to see textiles as art, see Brenda Lin’s article, “Textiles: The Art of Women’s Work,” on Sotheby’s website.

- For the AP World course curriculum on The Silk Roads and the Short-Answer Question rubric, visit the AP World: Modern website and Course and Exam Description.

Additional Reading

Rothchild, N. Harry. “First Ladies of Sericulture: Wu Zhao and Leizu.” In Emperor Wu Zhao and Her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers (New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2015), 60-74.

Stockard, Janice E. “On Women’s Work In Silk Reeling: Gender, Labor, And Technology In The Historical Silk Industries Of Connecticut And South China.” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 549 (2002): 272-281.