This resource is part of the Silk Roads and Beyond: Trade, Exchange, and Travel in Ancient and Medieval Afro-Eurasia toolkit, from the AHA’s Teaching Things project.

Introduction

There is a widespread perception that people in the premodern world, particularly during the Middle Ages, did not travel. While it is true that medieval travel looked different than it does today, people in that era did have reasons to leave home. For medieval people from Afro-Eurasia, travel often included—and extended beyond—trade. Their travels took them along many of the Silk Roads routes.

In this lesson, students will learn about the travel of two famous 14th-century Africans: Mansa Musa and Ibn Battuta. Through the lens of these figures, students will consider specific functions of travel, such as religious pilgrimage, as well as challenges of movement, technologies, and cross-cultural interactions.

Part I: Contexts

Watch this video by CrashCourse on the emergence and expansion of Islam in the Middle Ages (12:53 mins)

Watch this video by CrashCourse for a brief overview of Mansa Musa, Ibn Battuta, and Islam in Africa (10:30 mins)

Part II: Mansa Musa and the Catalan Atlas

The Mali Empire of medieval West Africa was a critical part of trans-Saharan trade networks. It controlled land with large quantities of gold deposits, and this precious resource, along with countless other goods, were traded in the urban commercial centers of Timbuktu and Gao.

In the early 14th century, Mansa Musa I was the leader of Mali. Mali was diverse and multiethnic, the result of longstanding cultural exchange within the region due to trade. Islam had been practiced in West Africa for centuries but was not adopted by the ruling class until just before Mansa Musa’s reign (1312–37). In 1324, he embarked on a hajj, or a pilgrimage to Mecca (in what is now Saudi Arabia), traveling through North Africa to reach the Arabian Peninsula.

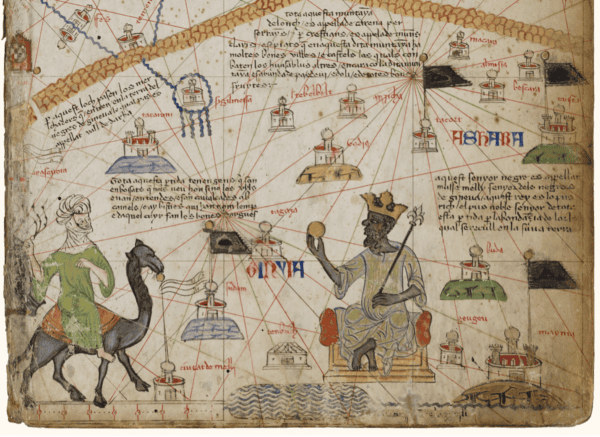

Multiple Arabic texts from the period mention Mansa Musa’s voyage and remark upon his considerable wealth and generosity. Thanks to his pilgrimage, the renown of Mansa Musa spread throughout much of the Mediterranean world. For example, Mansa Musa is depicted in the Catalan Atlas produced on the island of Majorca in 1375.

Ariel Fein provides background, context, and details useful for educators and students in “The Catalan Atlas,” Smarthistory, June 6, 2022.

Begin by having students explore the Catalan Atlas manuscript, which the Bibliothèque Nationale de France has digitized and published online via Gallica.

Classroom Discussion

(Adapted from Caravans of Gold Teacher’s Guide)

- What about this map is familiar to you? What is different or unexpected?

- What is the function of this map? Why do you think it was created?

- What kinds of objects, buildings, places, and people are depicted?

- How closely does this map represent the real physical world?

Looking closely at the bottom of folio (page) 7 for the depiction of Mansa Musa.

- Who are the two figures represented in the image? How are they depicted?

- Focus on the figure on the right:

- What objects can identify with this figure?

- What do these objects communicate about this person (i.e., position within society)?

- Make some inferences about what these objects were made of, and why those materials are important. (Hint: this is most easily seen by zooming in very closely on the digital image on Gallica.)

- Focus on the figure on the left:

- The caption next to this figure states that this land is “inhabited by people who go heavily veiled, so nothing can be seen of them but their eyes. They live in tents and ride on camels.” What does this explanation tell us about the nomadic people like the person pictured here?

- What does the portrayal of these figures tell us about the artist that illustrated and annotated these images? What might we be able to infer about their perspective or experience?

- Do you think these portrayals were based on direct experiences or from second- and third-hand accounts? Why?

- Focus on the figure on the right:

Part III: Ibn Battuta and Camels

Just a year after Mansa Musa left Mali on a hajj, another medieval African also embarked on the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca. In 1325, Ibn Battuta left Morocco to travel eastward. But instead of returning home after the religious journey, Ibn Battuta continued to travel the world for 29 years. He traversed approximately 75,000 miles and visited most of the territories that were then part of Dar al-Islam, or the Islamic world.

When Ibn Battuta returned to Morocco, his experiences were recorded in a text referred to as the Rihlah, or Journey, accessible online through the Internet History Sourcebook.

Have students read the following excerpt from the Rihlah and then look closely at the object below before considering the discussion questions. A large portion of Ibn Battuta’s travels required him to traverse deserts. In the following excerpt, he details his journey through the deserts of the Middle East and northern Arabian Peninsula. While this saddle likely dates to the 20th century, it is an example of traditional saddles used by the Tuareg and Imazighen people of northern Africa.

Crossing the desert from Syria to Medina

After a march of two days we halted at Dhat Hajj, where there are subterranean waterbeds but no habitations, and then went on to Wadi Baldah (in which there is no water) and to Tabuk, which is the place to which the Prophet led an expedition. The great caravan halts at Tabuk for four days to rest and to water the camels and lay in water for the terrible desert between Tabuk and al-Ula. The custom of the watercarriers is to camp beside the spring, and they have tanks made of buffalo hides, like great cisterns, from which they water the camels and fill the waterskins. Each amir or person of rank has a special tank for the needs of his own camels and personnel; the other people make private agreements with the watercarriers to water their camels and fill their waterskins for a fixed sum of money.

From Tabuk the caravan travels with great speed night and day, for fear of this desert. Halfway through is the valley of al-Ukhaydir, which might well be the valley of Hell (may God preserve us from it). One year the pilgrims suffered terribly here from the samoom-wind; the water-supplies dried up and the price of a single drink rose to a thousand dinars, but both seller and buyer perished. Their story is written on a rock in the valley.

Camel saddle (tarik or tamzak), Algerian Sahara. Date unknown (probably 20th century). Leather, rawhide, wood, parchment or vellum, wool, silk, tin-plated metal, brass-plated metal, iron, copper alloy, and cheetah skin. 975-32-50/11927. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, gift of the Estate of Dr. Lloyd Cabot Briggs, 1975, 975-32-50/11927. Photograph © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Discussion questions

- What is the function of a camel saddle? Why is using a saddle preferable to riding on an animal bareback?

- Identify the different kinds of materials that were used to make this object. What are their individual functions?

- Do you think a saddle like this was used for lengthy travel? Why or why not?

- Do the materials suggest who might have used a saddle like this?

- What is your impression of desert travel in the 14th century?

- What were the main challenges? How did people address or overcome them?

Part V: Wrap-Up

Discussion questions

- How did the spread of Islam to Saharan and West Africa influence the travels of Africans such as Mansa Musa and Ibn Battuta?

- What do the sources available tell us about trade and travel during this time period?

- What perspectives or lifestyles to these sources reflect?

- Which kinds of perspectives or lifestyles might they leave out?

- Would travel through the deserts of the Middle East and Africa have been possible without animals like the camel?

- What are some of the differences between medieval travel and modern travel?

Additional Resources

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, University of California, Berkeley

The Gold Road Project, Howard University

Caravans of Gold, Fragments of Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange Across Medieval Saharan Africa, Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University