From GI Roundtable 43: The Balkans—Many Peoples, Many Problems (1944)

Peaceful Farmers

Contrary to a widespread popular notion, the principal occupation of the Balkan peoples is not Raising Hell.

Enough of war, massacre, intrigue, and general bloodshed has taken place there to give some color to their reputation for violence, perhaps. But they are really no different from other people in their dislike of war and their desire to raise their families and work their land in peace and security. For most of the people who live in the Balkan Peninsula are farmers—plain and poor and often unlettered small farmers.

Greece, to be sure, is an important maritime nation—Greek ships and sailors have held a front rank in ocean commerce. But over 60 per cent of the seven million people of Greece are small farmers and stock raisers.

There are copper and lead and chrome mines in Yugoslavia, but 75 per cent of the sixteen million Yugoslavs live on the farms.

Bulgaria has cotton mills and tobacco factories, and Romania has oil fields, refineries, textile mills, and even some steel mills. But 80 per cent of the six and a half million Bulgarians and the same proportion of the sixteen million Romanians are small farmers.

In the fifth Balkan state, Albania, hardly any industrial development has taken place—perhaps 90 per cent of the one million Albanians are farmers and stock raisers.

The Balkan farmer may raise wheat in the fertile valleys of Romania, northeastern Yugoslavia, and northern Bulgaria; or olives, fruit, and tobacco in peninsular Greece and the Greek islands; or specialty crops like tobacco and roses for perfume in southern Bulgaria. Or he may be chiefly engaged in sheep raising in the rugged mountains of Albania, or pig raising in Yugoslavia. But whatever he raises, the farmer is in the overwhelming majority throughout the Balkans.

Through American Eyes

To an American used to measuring his fields in 40-acre lots or quarter sections or even larger units, the average Balkan farm would seem incredibly small. It commonly ranges from 1 or 2 to 10 or 15 acres. Rarely does it exceed the latter figure.

Moreover, the fields of a Balkan farm seldom lie all together in one place. Usually each farmer has several widely separated plots—a little good land in a valley, some thin soil on a slope, or a stony patch up a mountainside. Perhaps one field is able to produce wheat or corn or tobacco every other year or so, while another may be good for barley or vetch. A third may be suitable for a vineyard, the fourth, for a half-dozen or more olive trees, and so on.

An American would also note with surprise the almost complete absence of isolated farmhouses in the country. Balkan farmers regularly live grouped together in small communities, hamlets, or villages, from which in the early mornings they stream out in all directions to work their fields.

His holding may be small, but the Balkan farmer, at least in Greece, Bulgaria, and a large part of Yugoslavia, normally owns his land. He takes pride in his possession of it and clings to it with tenacity. From it he makes his frugal living. Only in Albania and Romania and parts of Yugoslavia is much of the land still owned by large landholders. There the small farmers are to a great extent poverty-stricken peasant-laborers.

Peace: The Balkan Puzzle

In the recent past the Balkan farmer has suffered from the effects of overpopulation, land shortage, and bad communications. He hasn’t had enough capital to develop the natural resources of his country. He will need long years of uninterrupted security to solve his problems.

Before the Balkan farmer can raise his standard of living, or before the basic economic ills of his region can be cured, there must be peace. Then new industrial establishments may develop and absorb the excess rural population; and then those left on the farms, who will still be a large majority, may learn new methods of intensive cultivation.

Some may object that there can be no peace unless the economic problems are solved first. It is true that peace probably will not last unless the agrarian population is contented. But it is surely a counsel of despair to say that there can be no hope for peace in the Balkans.

The newspapers are full of Balkan news, much of it puzzling.

General Mihailovich, who led the first Balkan guerrilla movement against the Axis, has been crowded off the front page. He is charged with easing up against the Germans, while a once mysterious figure named Tito is doing the fighting. He is said to have been fighting Mihailovich too. Why?

Exiled King Carol of Romania wants to broadcast to the United States from Mexico City, but there is a flood of protest and his speech is canceled. Why?

Why did King Boris of Bulgaria die suddenly in the summer of 1943 and why has his capital, Sofia, now been partly destroyed? The Greeks are reported opposed to the return of their king. Why, if that is true, don’t they want him back?

Why did the first World War start in the Balkans, and why didn’t this one? All these questions and many others are in the air.

The Mountains and the Sea

The peoples of the Balkans, being close to the land, have been molded by the character of the region they live in. Perhaps we can better understand them, then, if we begin by looking at the lay of the land.

Two of the Mediterranean peninsulas of Europe are cut off from the continent by lofty mountain ranges: Spain by the Pyrenees and Italy by the Alps. Although no equally high mountain range cuts off the third and most easterly peninsula, the Balkan, it is largely composed of rugged mountains.

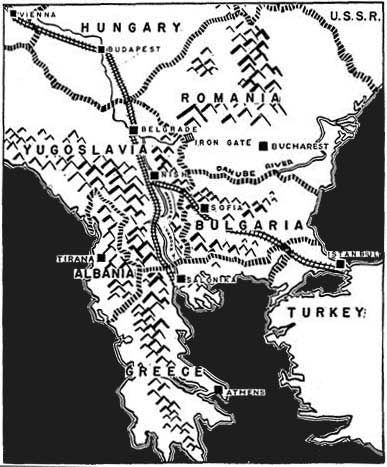

The Danube River, which is sometimes thought of as the northern geographical boundary, actually seems to link the Balkans with central Europe via the Hungarian plain. Romania, which lies almost wholly north of the Danube, is regularly included among the Balkan countries. And Hungary, because it is a Danubian country, and because it has controlled and asserts claims to territories inhabited by Yugoslavs and Romanians, is sometimes considered Balkan too.

When you look at a map of Europe, you can see that the Balkan Peninsula really consists of a broad northern section and the narrower southern peninsula of Greece, thrusting its irregular coast line into the Mediterranean. Despite its long seacoasts, washed by the Adriatic on the west and the Black Sea on the east, the wide northern portion of the Balkans is in general not maritime—partly because in the west the mountains run along the coast, with few seaports and few passages inland.

Greece, on the other hand, is essentially a Mediterranean country, and depends for its very existence on shipping and sea-borne commerce. This difference between the two parts of the peninsula helps set Greece somewhat apart from her neighbors.

The word “Balkan” means “mountain” in Turkish, and the mountains are perhaps the most distinctive physical feature of the region. In Romania; the Carpathians bend west and become the Transylvanian Alps. The same mountain fold then swings around a great reverse curve like a backward “S” and runs east all the way to the Black Sea. This last range is the Balkan Mountains. At the curve, where the Balkan range begins, the Danube flows through a gap in the mountain wall at the bottom of a famous and picturesque gorge called the “Iron Gate.”

On the Adriatic side of the peninsula a series of mountain ranges parallels the coast, from the Julian Alps in the far northwestern corner down through the Dinaric Alps in Yugoslavia and the Pindus Mountains in Greece. Between these two main ranges on the west and in the east there is a large central highland, also very mountainous, that covers southern Yugoslavia and almost all of southern Bulgaria.

These mountain chains and their many spurs cut the peninsula up into more or less isolated regions. Partly because of the difficulties of getting from valley to valley, many differences have developed between the various Balkan peoples, even within the populations of each of the states.

The Balkan Bridge

Although they cut up the area into isolated sections, the mountains of the Balkans provide no great barrier to through traffic. Two main avenues of passage, furrows between the mountain chains, make the peninsula a sort of bridge between Europe and Asia, over which, since time began, forces of conquest have streamed in both directions. Armies have marched, fought, and disappeared—Romans, Byzantine Greeks, Goths, Huns, Slavs, Crusaders, Turks, Venetians, the French, Austrians, Russians, Italians, Germans.

Today the railroads follow these two historic passageways. One avenue runs north and south. The Allied armies in World. War I produced a major German defeat by marching north along this route from Salonika, up the Vardar River Valley across the watershed and down the Morava River Valley to Nish and Belgrade. In the present war, the Germans have sadly admitted that they lost the North African campaign partly because Yugoslav guerrillas so often cut the Belgrade-Nish-Salonika railroad, which was carrying supplies to be shipped across the Mediterranean to Rommel’s army.

The other avenue runs east and west—between Nish and Istanbul via Sofia and Adrianople (Edirne). Nish, which is on both roads, is a vital junction. It has often been a target for Allied bombers.

In their passage across the Balkans, conquering armies have left the debris of many civilizations and different cultures. But the Balkan Peninsula can be thought of as more than a physical and military bridge between Europe and the Near East. It has also been a battleground of rival cultures, political systems, religions, and imperial powers. The peoples who live in the Balkans have inherited the experience of many centuries of war and oppression.

Related Resources

September 7, 2024

Travel and Trade in Later Medieval Africa

September 6, 2024

Sacred Cloth: Silk in Medieval Western Europe

September 5, 2024