From GI Roundtable 1: Guide for Discussion Leaders (1944)

For some time discussion groups and forums of one type or another have been an active part of off-duty education in many Army camps and commands. The success and persistence of many of these groups make it obvious that this is a kind of activity in which many Army men are interested. Research studies within the Army have found personnel to be equally interested in discussing problems related to the war and problems related to the home front.

For some time discussion groups and forums of one type or another have been an active part of off-duty education in many Army camps and commands. The success and persistence of many of these groups make it obvious that this is a kind of activity in which many Army men are interested. Research studies within the Army have found personnel to be equally interested in discussing problems related to the war and problems related to the home front.

It is to be expected, however, that a relatively small proportion of any organization will show sustained interest in organized discussion as a phase of the off-duty educational program. For those who are interested, there is no better way of strengthening their understanding of the war and consequently their morale than by mental exercise on significant and worth-while questions. Their minds, in any case, will be inquiring and active. Thinking troublesome problems through will strengthen then good morale. That, in turn, is likely to become contagious and to have a good effect upon the morale of others who do not join in the discussion groups.

Any military personnel may want to join voluntary discussion: officers, warrant officers, enlisted men, WAC personnel, or nurses. Groups made up of all these classes of individuals have been successfully organized. The decision whether to limit attendance to one or more of these classes must be made in light of local conditions within the command. It is not impossible also that civilians who work and live at an Army post may want to join in organized discussion. In most instances, it is preferable for them to have their own group; but again in this matter the local situation will rule. Whatever decision is made to limit attendance should be taken with the purpose of creating favorable conditions for freedom and informality in discussion.

To organize a successful discussion group it is essential to determine, first, the questions that the men will want to discuss. The special interests of the men at the time of organizing the first meetings in particular must be taken into account. Remote and academic topics will misfire; topics of immediate concern to the men will enable the leader to reach his objective. (See Section III, Choosing subjects.)

An officer responsible for organizing a voluntary discussion group is advised to do more than announce that at 1930 on Thursday there will be a meeting of interested personnel to organize discussions of current and postwar issues. The leader or sponsor of the group should do some spade work first.

1. An interest questionnaire: A short questionnaire can be quickly prepared and mimeographed. It should contain two types of questions. The first will inquire whether the men are interested in an opportunity to discuss under informed leaders subjects having to do with war and postwar problems; whether they would prefer to hear an expert give a short talk on the problem, to be followed by questions; or whether they would prefer simply to hear special lecturers. The second type of question will endeavor to discover interests in specific questions. Three ways of getting this information are suggested: One is to let the men make a free choice by writing the subjects they would choose on several blank lines following a statement like: “On the lines below write the subjects which you would like to discuss.” A second way is to list a dozen or more subjects selected from among international, national, community, and personal problems. After each subject a blank is provided. The instruction accompanying the list should ask that from three to five choices be checked. A third way is to combine the two methods above. Below the check list the man may be asked to write on blank lines any subject in which he is interested, but which has not been included in the list. For a suggested questionnaire see Figure 1.

The leader (officer or enlisted man) preparing the questionnaire will decide whether he will get more authentic information from the men by having the questionnaires unsigned. The disadvantage of using unsigned questionnaires is that an opportunity is lost to secure the names of interested individuals.

2. Announcement: Once the plans for holding a meeting are made, interest may be stimulated or maintained by announcements in the camp newspaper, over the local broadcasting system, on slides during movie showings, or at formations. Such announcements are useful whether they deal with preliminary meetings to determine group interests or with information about the time, place, and subject of a specific discussion that has been decided upon.

2. Announcement: Once the plans for holding a meeting are made, interest may be stimulated or maintained by announcements in the camp newspaper, over the local broadcasting system, on slides during movie showings, or at formations. Such announcements are useful whether they deal with preliminary meetings to determine group interests or with information about the time, place, and subject of a specific discussion that has been decided upon.

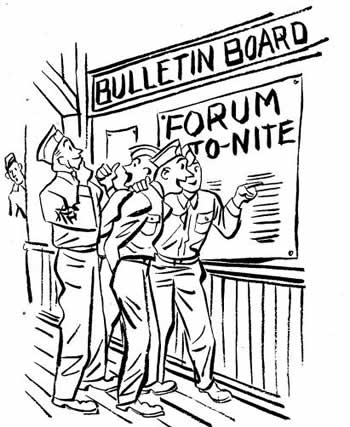

3. Bulletin boards: An obvious way to stimulate interest in discussion groups—proposed or already functioning—is to maintain well-located bulletin boards. Posters, maps, newspaper clippings, and photographs should be effectively arranged. A clearly printed heading which gives the discussion subject can be used to tie the whole exhibit together.

3. Bulletin boards: An obvious way to stimulate interest in discussion groups—proposed or already functioning—is to maintain well-located bulletin boards. Posters, maps, newspaper clippings, and photographs should be effectively arranged. A clearly printed heading which gives the discussion subject can be used to tie the whole exhibit together.

Another bulletin board device is to make a list of intriguing questions which are bound to come up during the discussion. Arrange them under some such heading as “Do you ever wonder?” and place a slogan below like “Come to ___ and get the answers.”

Material on bulletin boards should be regularly changed. Bulletin boards on which exhibits are not constantly changed are of no value whatsoever.

You do not have to discard the idea of posters and maps because you cannot requisition them. Homemade ones—there’s at least one fair artist in every outfit—are often more interest-provoking than professional productions. Every aggregation of men follows with interest the creations of its members.

4. Movies: Films shown in the Army often leave unanswered questions in the minds of the audience. The leader can capitalize upon these by timing the discussion of a particular issue immediately after the showing of a stimulating film. For example, “The Battle of Russia” in the “Why We Fight” series may stimulate a lively discussion on the postwar aspirations of the U.S.S.R.

Similarly G. I. Movie releases often provide provocative discussion material; G. I. Movie Release No. 15 contains a section called “The Dutch Tradition,” which may be used as a starting point for talking over what should be done about colonies in the postwar period.

5. Exhibits of books and periodicals: Librarians know how to arrange exhibits for the purpose of suggesting reading to the men. Similar exhibits related to a subject chosen for discussion may be arranged by the leader with the help of a librarian and can be set up in either library or service club. By suggesting preliminary reading, exhibits will not only stimulate interest in an announced discussion, but will also lead to more informed discussion on the part of group members who do some reading. The exhibits, tied in with discussion plans by means of an arresting poster or card, can be used either to promote the idea of group discussion or a particular meeting that has been announced. The advantages of library or service club exhibits of books and periodicals are two. These exhibits are seen by large numbers of men when their minds are relaxed and receptive. Second—and this is particularly true of library exhibits—they are seen by officers and men who have sufficient intellectual interest to search for reading materials. Among this type of personnel are found the individuals who will most desire to take part in discussion.

5. Exhibits of books and periodicals: Librarians know how to arrange exhibits for the purpose of suggesting reading to the men. Similar exhibits related to a subject chosen for discussion may be arranged by the leader with the help of a librarian and can be set up in either library or service club. By suggesting preliminary reading, exhibits will not only stimulate interest in an announced discussion, but will also lead to more informed discussion on the part of group members who do some reading. The exhibits, tied in with discussion plans by means of an arresting poster or card, can be used either to promote the idea of group discussion or a particular meeting that has been announced. The advantages of library or service club exhibits of books and periodicals are two. These exhibits are seen by large numbers of men when their minds are relaxed and receptive. Second—and this is particularly true of library exhibits—they are seen by officers and men who have sufficient intellectual interest to search for reading materials. Among this type of personnel are found the individuals who will most desire to take part in discussion.

6. Organizing committees: Either before promoting a voluntary discussion group or very soon after the initial publicity, it may be an excellent plan under some circumstances to invite a half dozen officers and men to form an organizing committee. The purpose of having such a committee is to start the group off with the established policy of having members of the group determine their own program. More sustained interest in any voluntary activity is often secured if the participants have a share in deciding its methods and specific objectives. The suggestion for the inclusion of both officers and enlisted men is made because it has been found by experience that free discussion on a common ground by both adds greatly to the interest in the activity. Officers who join with enlisted men for this purpose must act as fellow inquirers if the full benefit of such a joint activity is to be attained.

Naturally care must be exercised in the selection of men invited to form the committee. It is preferable to invite those who may have already expressed interest in the program. It will assist the work of the committee if some of them have had experience on similar committees in professional, business, or community life. Each one should ideally have two characteristics. His intellectual interests should be such that he realizes the importance of a citizenry informed on public issues and that he understands the value of discussion as a method of study. His personality should be one that will enable him to sell the program to other men with whom he is associated.

Naturally care must be exercised in the selection of men invited to form the committee. It is preferable to invite those who may have already expressed interest in the program. It will assist the work of the committee if some of them have had experience on similar committees in professional, business, or community life. Each one should ideally have two characteristics. His intellectual interests should be such that he realizes the importance of a citizenry informed on public issues and that he understands the value of discussion as a method of study. His personality should be one that will enable him to sell the program to other men with whom he is associated.

7. Personal invitations: Usually it is possible to discover what individuals are likely to have special interest in forums and discussion groups. Interest questionnaires, if signed, will give one clue. Casual conversation may offer another. Members of such a committee as that described above should be able to supply names of other persons also. The officer or enlisted man who is organizing the program would do well to jot down any names he is able to secure in the course of his normal contacts with others. Both leader and committee members can stimulate interest in the meetings by issuing personal invitations to attend.

Related Resources

September 7, 2024

Travel and Trade in Later Medieval Africa

September 6, 2024

Sacred Cloth: Silk in Medieval Western Europe

September 5, 2024