By Robert Ulich

Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education

(Published December 1945)

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

How Did the Germans Get That Way?

Are There Factors Favorable to Re-Education?

Will Postwar Germany Want to Be Re-Educated?

Who Should Teach in Germany’s Schools—and What?

Is Formal Education the Only Way to Re-Education?

Can Adult Germans Be Re-Educated?

Can Conditions for Re-Education Be Established?

Introduction

The re-education of [the German] … people may be difficult indeed…. For the victors to rely upon force alone would be futile. Any order, which hopes to survive, must ultimately appeal to the minds of men.—Harry S. Truman, January 29, 1945

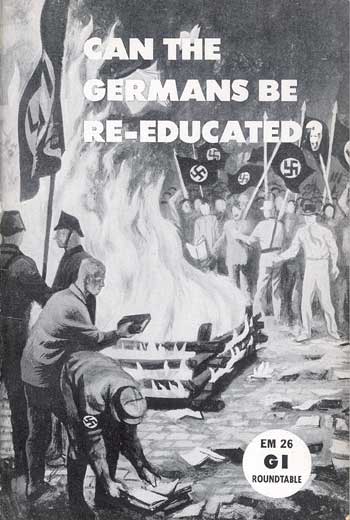

Hitler’s Reich was to last a thousand years. It lasted twelve years and three months. Amid its ruins and ashes the Four Powers—the United States, Great Britain, Russia, and France—are now carrying forward certain policies.

First among them is that Germany must be deprived of the means of making war. The most obvious way to make sure that Germany never again starts a world conflict is to see that Germany is stripped of arms.

That, in the long-time view, is a negative kind of policy. It requires enforcement and supervision from the outside. It presumes that the Germans will always want to break loose if they can get their hands on weapons, and therefore it requires either permanent military occupation of Germany or very close supervision coupled with the constant threat of occupation.

No American can examine this policy without immediately sensing that it is alien both to our deep dislike of ruling other people against their will and to our equally deep dislike of keeping an army of occupation in Europe any longer than necessary.

For us, occupation as long, as necessary means only until the Germans no longer hunger for domination and war. That, in turn, means a fundamental change in the outlook of the German people. It means their re-education to be good citizens-and to want to be good citizens-in a peaceful and orderly world.

In the long-time view, all policies that do not contribute to the achievement of this positive purpose will be open to challenge. But before we turn away from the purely negative aim of keeping the Germans from trying aggression again we have to know if a positive aim will succeed. Will we be sorry some day if we build on the hope that a future Germany, chastened and peaceful, can ask for readmittance to the family of nations? Must we forever fear and suppress them, or can the Germans be re-educated?

Related Resources

September 7, 2024

Travel and Trade in Later Medieval Africa

September 6, 2024

Sacred Cloth: Silk in Medieval Western Europe

September 5, 2024