Summary: Respondents weighed in on various sources of the past and how much those sources encouraged them to learn more history. As we have seen in respondents’ thoughts on other areas of historical sources, there is more variability than consistency between engagement, trustworthiness, and utilization. Survey results also show that the majority of people see distant people, places, and topics as equally important to more proximate ones, though there are often double-digit differences between subgroups.

It is natural for people to have inclinations toward or away from various areas of the past. Those inclinations, however, run the risk of limiting historical knowledge and curiosity, such as when individuals care about what affects them personally and little else. Restricted interests and knowledge also severely limit the scope of information that can be brought to bear on issues, which can result in people living with a veritable “perpetual now” mindset, where all situations are without historical parallel or precedent. One of history educators’ goals, it seems to us, is to broaden society’s interests and push people into unknown, even uncomfortable confrontations with the past. Survey results indicate the public is open to such persuasion (see for example Figure 50).

One way to broaden society’s historical interests is to understand which sources of the past foster the greatest interest in learning. This is not to say that educators should favor certain types of sources over others, since all types have their inherent strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, prodding learners to struggle with challenging or unfamiliar materials can lead to significant educational gains.

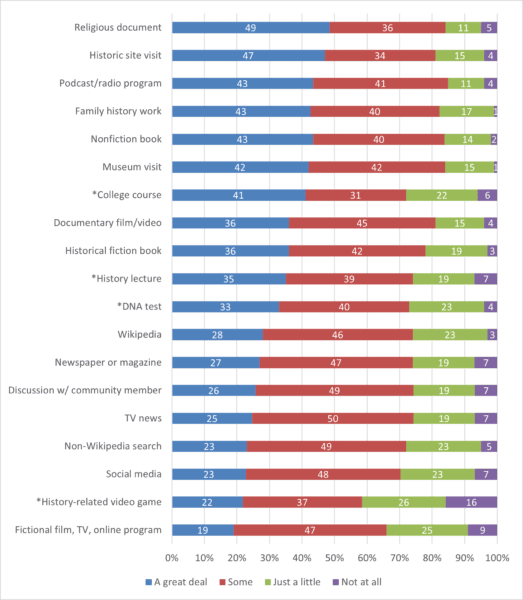

The results in Figure 69, where respondents registered degrees to which various sources encouraged them to learn more history, are worth considering. Even more interesting is to compare these results with Figure 14 (utilization of sources of the past) and Figure 26 (trust placed in sources of the past). Such comparisons reveal that religious documents spurred the most interest, even though the degree to which they were consulted was only middling, and despite coming in fifth place in terms of trustworthiness. Other sources saw rather stark inversions. Podcasts ranked high in piquing interests but fared poorly in terms of utilization and trust. Documentary films and videos received very high marks for accuracy and utilization, but mediocre ones for inciting interest in the past. Museums, the most trusted venues of history, were only in the top third as motivators to learn more, and only the top half for utilization. Views toward fictional film and TV bordered on schizophrenic: with abysmal rankings for trustworthiness and fostering more learning, but very high utilization rates. There were also some constants. Social media and history-related video games were perennial bottom-feeders across all categories.

Figure 69: Survey respondents’ reported degrees to which various sources motivated them to learn more history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (S4a)

Figure 69: Survey respondents’ reported degrees to which various sources motivated them to learn more history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (S4a)

Such incongruent results reinforce and build upon a point made in Section 4, namely that the sources to which the public turns most often for information about the past are not the same ones that are most trusted or likely to provoke more interest. Whether historians should try to somehow bring all three measures into alignment as some sort of pedagogical holy grail is probably moot. Rather, it is likely more a case of teaching the inherent potentials and pitfalls of a variety of source types, while selecting those that are most conducive to a given educational goal.

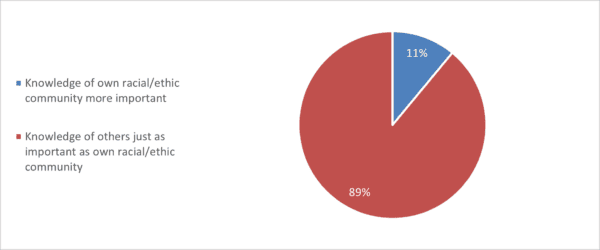

The survey also attempted to capture which historical subjects most interested the public. Much strife and pain has been associated with matters of race and ethnicity in recent years, including the imbroglio over the teaching of “critical race theory.” It is thus essential to point out that 89 percent of our respondents said that knowledge of the history of others was just as important to know as was knowledge of the respondents’ own racial or ethnic communities (Figure 70). Whether this represents genuine sentiments or is tinged by social desirability is uncertain, but such data show how unreflective some headline-grabbing controversies are of the broader American public’s views.

Figure 70: Survey respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 70: Survey respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

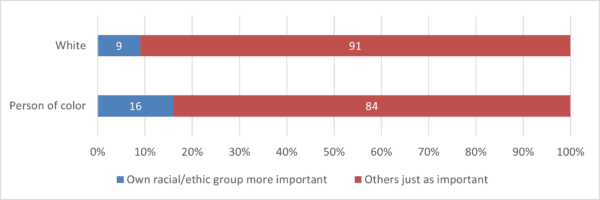

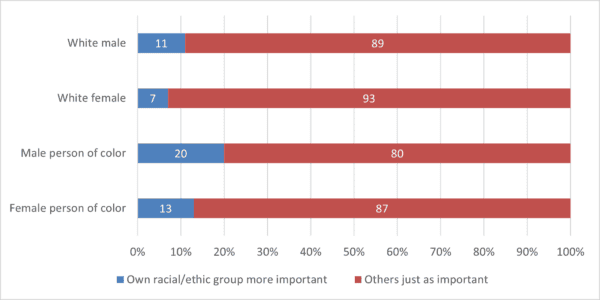

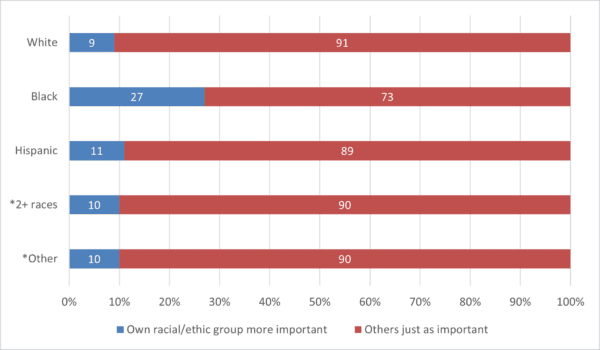

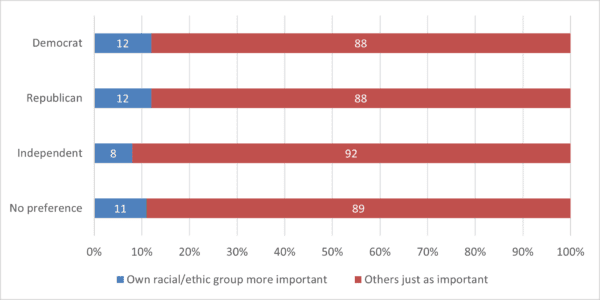

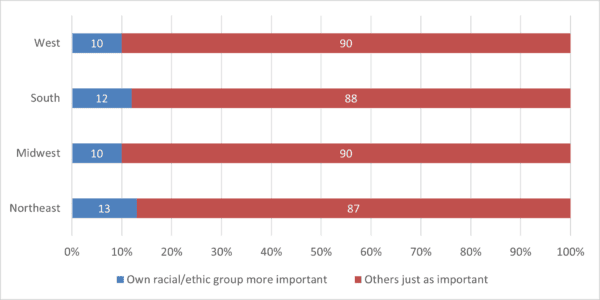

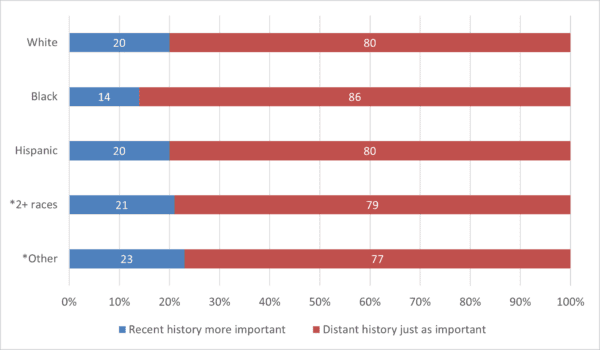

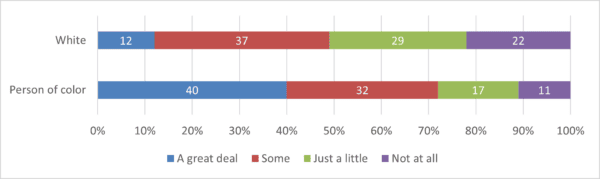

Cross-tabulations show that people of color were more likely (though never overwhelmingly so) to favor knowing the histories of their own racial or ethnic groups than were whites (Figure 71). Breaking things down further, men of color were most inclined to find interest in their own communities, while white women were the least (Figure 72). African Americans were most likely to favor their own history, though only 27 percent believed that knowledge of other racial/ethnic groups was somehow less worthy of attention (Figure 73). Political party affiliation (Figure 74) and region of the country (Figure 75) seemed not to matter, as results largely replicated topline figures. Clearly, there is a lot more toleration and even interest in those of other racial/ethnic groups than politicians and the media would lead us to believe.

Figure 71: By race: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 71: By race: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 72: By gender/race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 72: By gender/race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 73: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V4)

Figure 73: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V4)

Figure 74: By political party: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 74: By political party: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 75: By region: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Figure 75: By region: Respondents’ views on the importance of racial or ethnic community history. (V4)

Just as other racial and ethnic groups can seem foreign to outsiders, so can the distant past seem to those in the present. Humans live through only thin slices of “history,” however defined. That being the case, is the public as interested in what transpired more than 100 years ago as it is in more recent events?

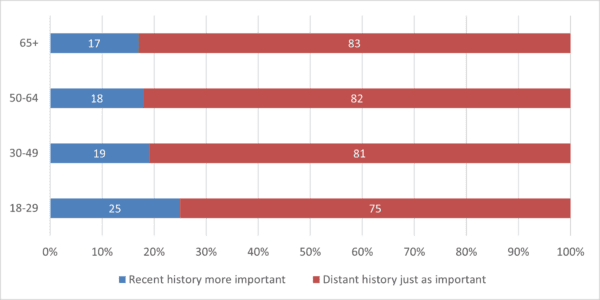

The survey exposed general interest in things beyond a typical lifespan, with 81 percent of respondents saying that events from a century ago are just as important as more recent ones. This suggests empathy for the more distant past, though decidedly less so than for people of different races and ethnicities, as outlined above. Perhaps unsurprisingly, age made a difference: the older the respondents, the more likely they were to value things further back in time (Figure 76). Notable outliers were African Americans, who voiced nominally more support for distant events than did other racial and ethnic groups (Figure 77). Results consistent with topline figures marked other demographics.

Figure 76: By age group: Respondents’ views on the importance of events over 100 years ago. (V5)

Figure 76: By age group: Respondents’ views on the importance of events over 100 years ago. (V5)

Figure 77: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the importance of events over 100 years ago. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V5)

Figure 77: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the importance of events over 100 years ago. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V5)

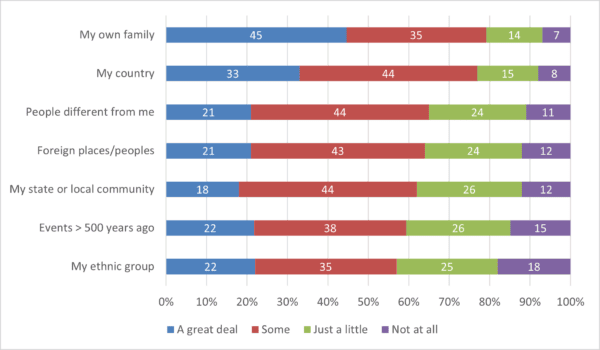

Another survey item adds context to the reported attitudes toward ethnic communities and the distant past. That item asked respondents how interested they are in learning about seven different historical fields. As shown in Figure 78, 57 percent voiced great or some interest in learning more about their own ethnic group, while the number was 60 percent for events from over 500 years ago (i.e., premodern history, as opposed to just a century ago). While those are majority figures, they are the lowest of the seven choices. In fact, these two topics also registered the highest levels of uninterest from respondents. The greatest importance fell to the item closest to home: the family (80 percent answered great or some interest, combined). Despite this professed curiosity for things familial, note that respondents reported elsewhere only infrequently partaking in genealogy work and DNA testing (Figure 14), thus showing how an indirect measure can differ from a more direct one. And while national history took the second spot at 77 percent combined, another survey item found that 82 percent of respondents thought it was just as important to know about foreign history as US history—a higher number than the 64 percent combined interest in foreign places/peoples shown in Figure 78.

Figure 78: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the histories of seven topics. (S7)

Figure 78: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the histories of seven topics. (S7)

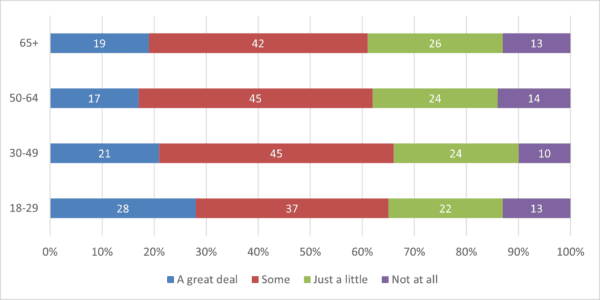

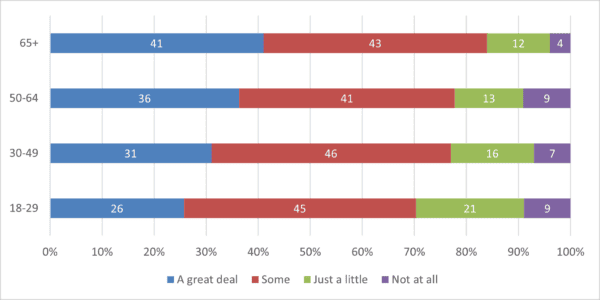

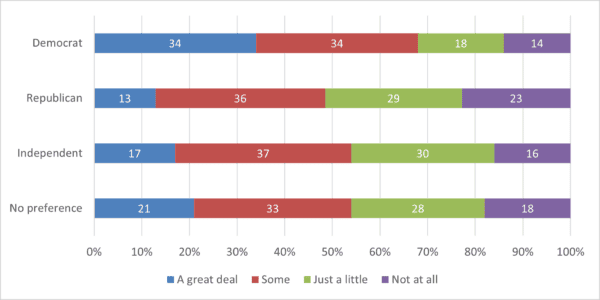

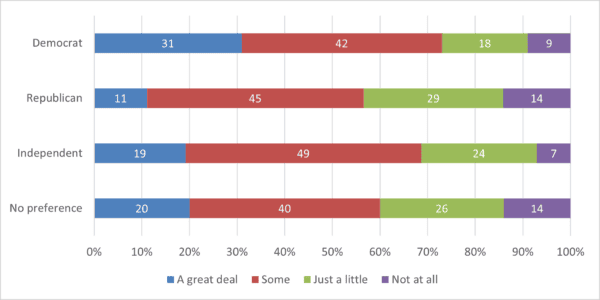

Some notable trends and differences in these attitudes appeared when broken down by demographic groups. For example, younger age cohorts registered greater interest in foreign places or peoples than did their older counterparts (Figure 79), but that trend reversed when it came to the importance of one’s own country (Figure 80). People of color were far more concerned with learning more about their own ethnic group than were whites (Figure 81), yet those two demographics were largely on par in the other six areas. The effects of politics showed through as well. Democrats displayed considerably more interest in learning about their own ethnic groups (Figure 82) and people perceived as different (Figure 83), while Republicans voiced somewhat greater curiosity about the history of their own country (Figure 84).

Figure 79: By age group: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the histories of foreign places or peoples. (S7)

Figure 79: By age group: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the histories of foreign places or peoples. (S7)

Figure 80: By age group: Interest in learning more about the history of own country. (S7)

Figure 80: By age group: Interest in learning more about the history of own country. (S7)

Figure 81: By race: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the history of own ethnic group. (S7)

Figure 81: By race: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the history of own ethnic group. (S7)

Figure 82: By political party: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the history of own ethnic group. (S7)

Figure 82: By political party: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the history of own ethnic group. (S7)

Figure 83: By political party: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the histories of people who are different. (S7)

Figure 83: By political party: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the histories of people who are different. (S7)

Figure 84: By political party: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the history of own country. (S7)

Figure 84: By political party: Respondents’ interest in learning more about the history of own country. (S7)

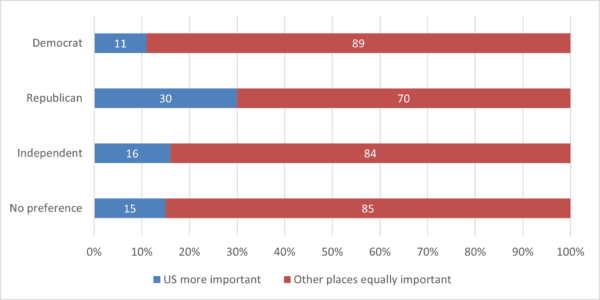

The centrality of US history was also measured from the angle of how important respondents felt it was when compared against non-US history. Data on this issue show that a majority always expressed a great deal or some interest in American history, but comparing this topic directly against the histories of foreign places yielded only 18 percent who thought the US should be privileged (the majority 82 percent felt the two were equally important). Those proportions held remarkably steady across age groups, education levels, genders, races/ethnicities, genders/races/ethnicities, and regions of the country. The one cross-tabulation generating substantial disagreement was political party identification, where Republicans and Democrats split by wide margins (Figure 85). These findings put the differences shown in Figure 84 in even starker relief.

Figure 85: By political party: Respondents’ views on the importance of US history versus non-US history. (V3)

Figure 85: By political party: Respondents’ views on the importance of US history versus non-US history. (V3)

Challenges and opportunities: News headlines would have us believe that the country is hopelessly divided, but the results in this section paint a different picture, at least in theory. Despite some real demographic disparities, we see that the majority of respondents were quite tolerant of, even interested in, learning about people, places, and events far removed from themselves. While some sources of the past resonate with the public more than others, we note that all of them motivate at least half of respondents to learn more history. Whether that range of interests and source materials is being adequately exploited by the professional historians to reach the public is an open question.