Summary: Just because the public frequently turns to a particular source for information about history does not necessarily make that source trustworthy in respondents’ eyes. Tangible repositories of the past such as museums and historic sites take top billing here, with fictionalized versions of history and social media at the other pole. Within those topline results, however, are substantial discrepancies among demographic groups.

There is no rigorous empirical order for the trustworthiness of sources of the past. Eyewitness accounts, for example, are always important, but they can also be unreliable. Professional historians often look askance at Hollywood versions of history, but films are valuable cultural artifacts that, even when highly embellished, might be particularly effective at conveying broader lessons about the past and a society’s understandings thereof. Similar dualities attach to the other sources used here. As such, this section discusses the public’s perceptions of source trustworthiness, bearing in mind that no agreed-upon ranking exists.

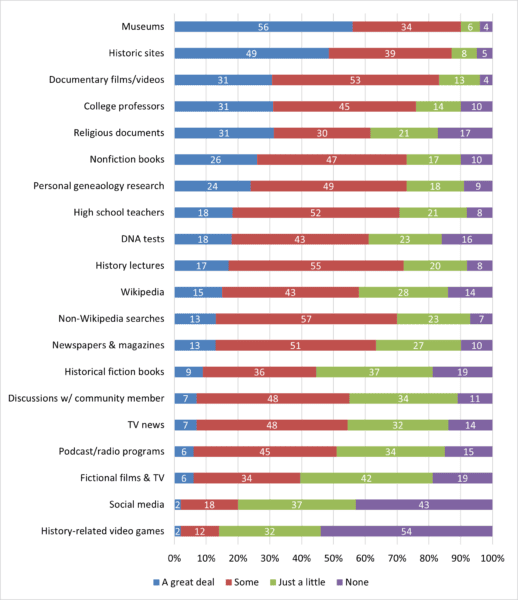

As seen in the previous section, the American public has definite preferences for where it gets information about the past. That said, the most frequently consulted sources were not necessarily considered the most trustworthy. For example, although fictional films and television programs were the second-most popular sources of history, they ranked near the bottom in terms of trustworthiness. Meanwhile, museums were of only middling popularity, but took the top spot for historical dependability. College history professors garnered fourth position as reliable informants, even though the nonfiction work they produce, let alone the courses they teach, were infrequently consulted by respondents. Similar inversions occurred for TV news, newspapers and newsmagazines, non-Wikipedia web search results, and DNA tests. (For all these cases, compare Figure 14 with Figure 26.)

Figure 26: Survey respondents’ trust placed in 20 sources to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 26: Survey respondents’ trust placed in 20 sources to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

These anomalies suggest that the public looks for information about the past where it is convenient or entertaining, not necessarily where it is trustworthy. Thus, although museums and historic sites are perceived as reliable places to gain knowledge about the past, the intentionality required to interact with them suggests they are consulted somewhat infrequently. Nonfiction books are seen as reasonably dependable sources of history, but they might require greater effort to obtain and engage with, leaving them underutilized. The costs involved in DNA testing might make it prohibitive to many persons, despite its reputation as a reliable vehicle for information about the past.

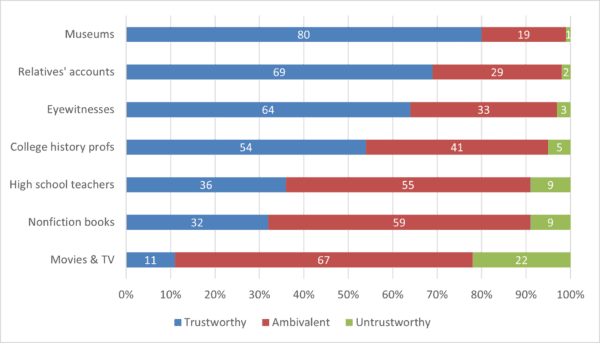

The public’s great faith placed in museums deserves special attention. In their survey from the 1990s, Rosenzweig and Thelen likewise found that museums were the most trusted sources of information about the past (Figure 27), so this notion has not budged in the aggregate over nearly three decades, although it becomes complicated when parsed for various demographics (see later in this section).

Figure 27: Trust placed in seven sources to provide an accurate account of history, on a ten-point scale. “Trustworthy” = scores of 8–10; “ambivalent” = 4–7; “untrustworthy” = 1–3. Based on Rosenzweig and Thelen, Presence of the Past, Table 1.3, p. 21.

Figure 27: Trust placed in seven sources to provide an accurate account of history, on a ten-point scale. “Trustworthy” = scores of 8–10; “ambivalent” = 4–7; “untrustworthy” = 1–3. Based on Rosenzweig and Thelen, Presence of the Past, Table 1.3, p. 21.

Why is so much faith placed in museums? The present survey did not drill down further into the issue, but project co-author Burkholder has informally investigated this matter with his undergraduates many times over the years. In his experiments, museums are always the top choice of students seeking the most trustworthy information about the past. When asked why this is the case, respondents’ answers boil down to two main categories.

First, objects in museums are perceived as not only representing history but being history. Those objects are thus assumed to be unbiased links to the past, which differentiates them from mere facsimiles of history such as researchers’ books and articles. Of course, survival, selection, and display biases attach to museum objects, but those shortcomings rarely occur to museum visitors.

A second oft-heard explanation is that museums are collaborative enterprises. The fact that many people are presumed to be involved in displays, explain students, serves as a form of quality control against misrepresentation. Asked about quality-control issues in the production of traditional historical scholarship, few learners are aware of legitimate versus nonlegitimate publication venues, the peer-review process, or the reality that researchers collaborate with other academics in the form of using and referencing previous scholars’ works. These conclusions remain tentative, but they may point to an important breach between professional historians and the public they serve.

That said, some consistencies between source utilization and perceived trustworthiness stand out. Respondents viewed history-related video games as highly unreliable sources of the past, and they utilized these games infrequently as well. Social media was deemed untrustworthy, ranking near the bottom of the pack, while only a quarter of respondents reported turning to it for historical information. Religious documents moved only slightly, from 7th out of 19 in terms of use to the top quartile for reliability. (For all these findings, compare Figure 14 with Figure 26.)

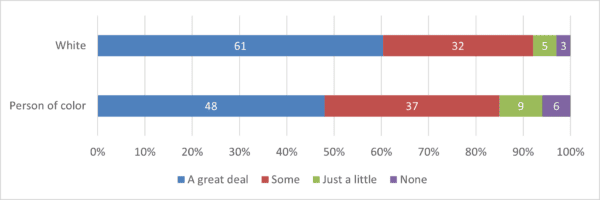

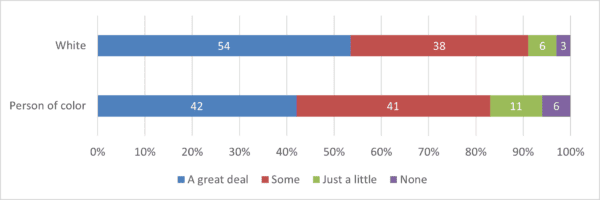

Cross-tabulations yield other results of note. Although museums and historic sites occupied first and second place, respectively, as trustworthy sources of the past overall (Figure 26), people of color and whites registered starkly different views. As for who trusted museums a great deal, a 13-point spread separated these two groups, while a 12-point difference applied to historic sites (whites were more trusting in each case). At the other end of the spectrum, people of color were twice as likely to view these sources of the past as not at all trustworthy, though such numbers were quite small overall (Figure 28 and Figure 29). Elsewhere, whites and people of color had mostly similar views on other sources’ reliability.

Figure 28: By race: Respondents’ trust placed in museums to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 28: By race: Respondents’ trust placed in museums to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 29: By race: Respondents’ trust placed inhistoric sites to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 29: By race: Respondents’ trust placed inhistoric sites to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

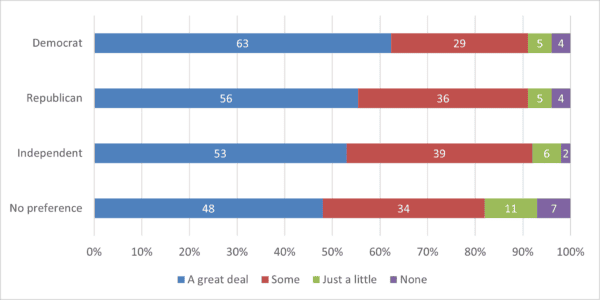

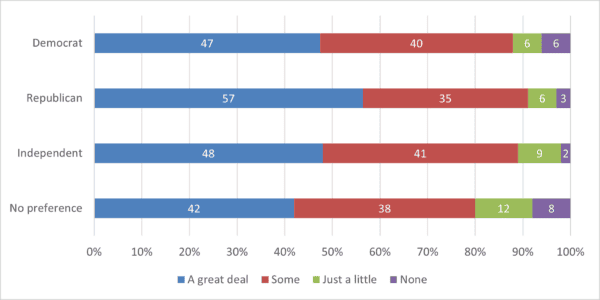

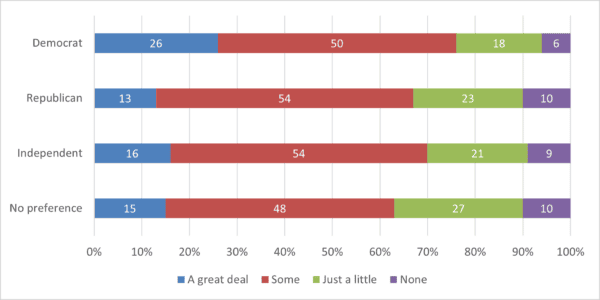

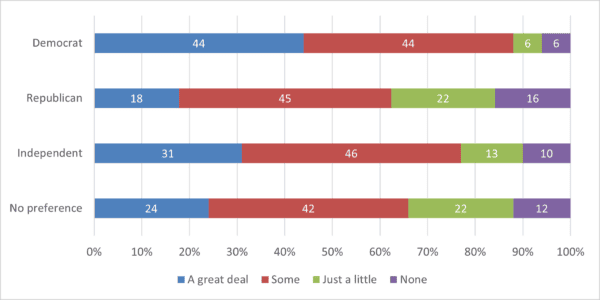

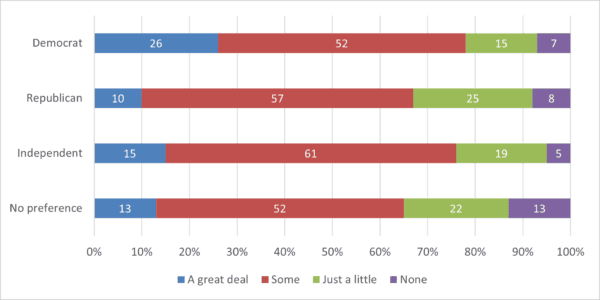

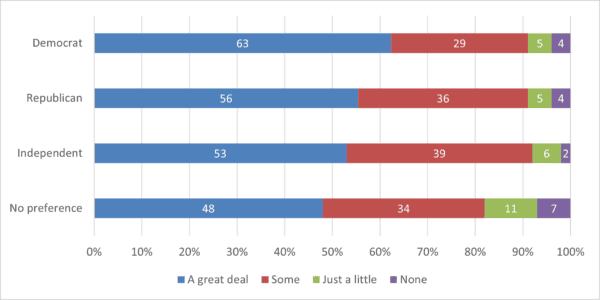

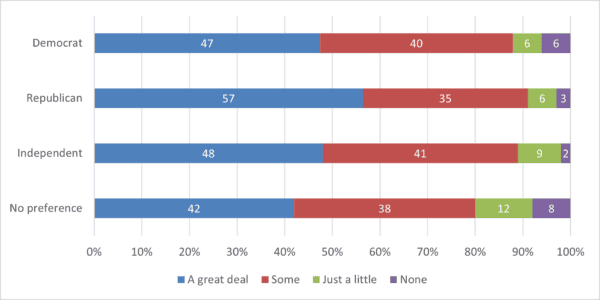

Survey results further indicate that museums and historic sites carry partisan baggage. Democrats were more likely to place a great deal of trust in museums than were other party affiliates (Figure 30), while Republicans’ strong faith in historic sites surpassed all others’ by at least nine points (Figure 31).

Figure 30: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in museums to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 30: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in museums to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 31: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed inhistoric sites to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 31: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed inhistoric sites to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

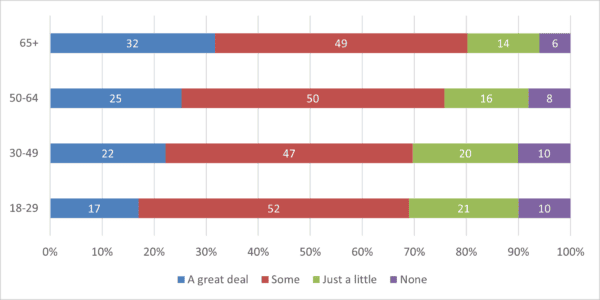

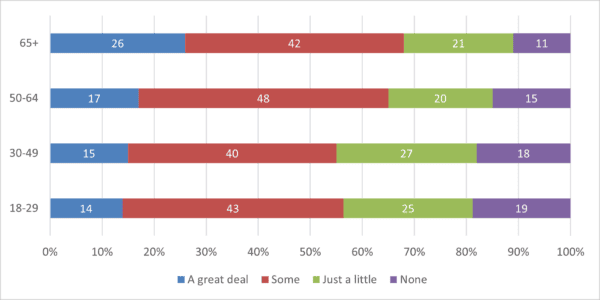

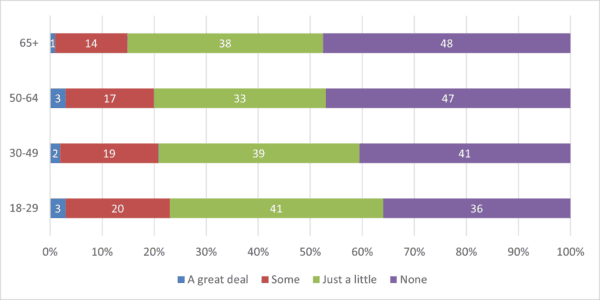

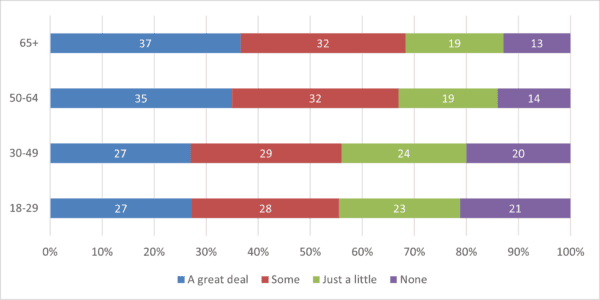

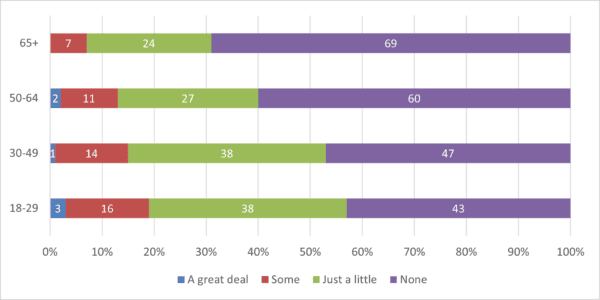

Views on the trustworthiness of sources of the past were fairly uniform by age groups. However, there were notable differences for several sources: family genealogy research (Figure 32) and DNA testing (Figure 33), where older respondents saw such work as more reliable than younger ones; social media, where younger respondents were less apt to view it as not at all reliable than were their elders (Figure 34); religious texts, where respondents became more trusting as they aged (Figure 35); and history-themed video games, where older age-bands were far more distrustful than were their younger counterparts (Figure 36). These differences may be explained by greater or lesser familiarity with specific sources as a function of age, though the survey has no direct data to this point.

Figure 32: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in family genealogy research to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 32: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in family genealogy research to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 33: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in DNA testing to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 33: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in DNA testing to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 34: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in social media to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 34: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in social media to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 35: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in religious texts to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 35: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in religious texts to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 36: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in history-related video games to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 36: By age group: Respondents’ trust placed in history-related video games to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

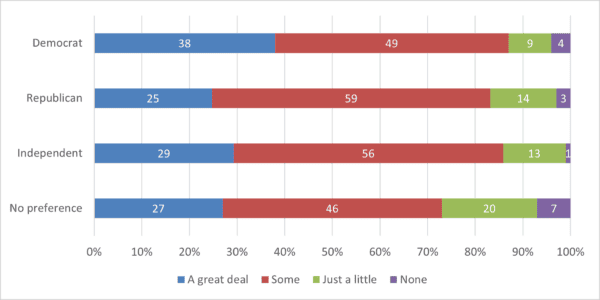

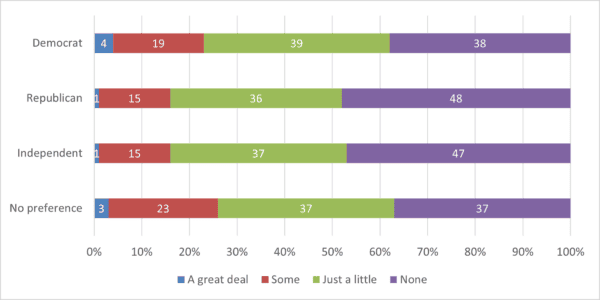

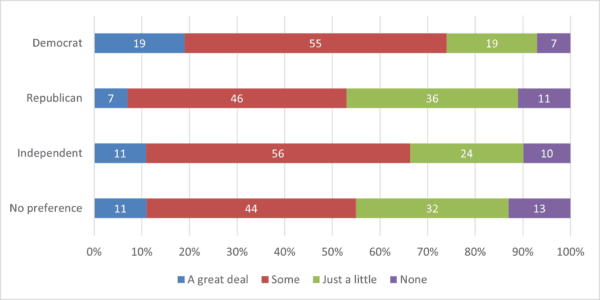

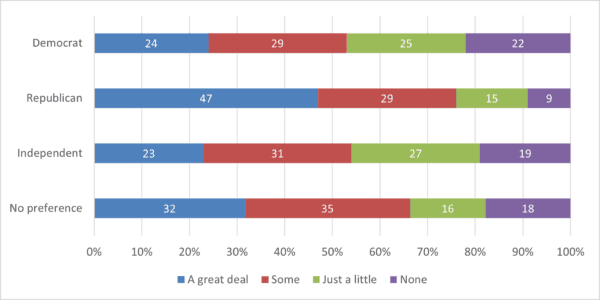

There are some stark divisions as a function of political party affiliation. Emblematic of the ongoing “history wars” are the contrasting views on high school and college-level teachers, where Republicans indicated they were far less trusting of the educational system than their Democratic counterparts (Figure 37 and Figure 38). Perhaps unsurprisingly, a similar dynamic applied to confidence in public history lectures (Figure 39). Other conflicting cases pertained to documentary films and videos, in which Democrats were more likely to place a great deal of trust than were Republicans (Figure 40); social media, where Republicans and independents alike registered considerably greater skepticism than did Democrats and those with no preference (Figure 41); newspaper and magazine articles, which were deemed a great deal or somewhat more trustworthy by Democrats and independents, relative to Republicans and those with no party preference (Figure 42); and religious texts, where Democrats and Republicans differed prominently at the two poles (Figure 43). Even the perceived reliability of museums and historic sites—the two sources of the past that rated the highest overall (Figure 26 above)—came down to political leanings. Democrats were more likely to place a great deal of trust in museums than were their Republican counterparts (Figure 44), while that relationship flipped when it came to historic sites (Figure 45).

Figure 37: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in high school teachers to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 37: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in high school teachers to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 38: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in college and university professors to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 38: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in college and university professors to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 39: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in public history lectures to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 39: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in public history lectures to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 40: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in documentary films or videos to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 40: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in documentary films or videos to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 41: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in social media to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 41: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in social media to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 42: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in newspapers or magazine articles to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 42: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in newspapers or magazine articles to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 43: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in religious texts to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 43: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in religious texts to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 44: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in museums to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 44: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in museums to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 45: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in historic sites to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Figure 45: By political party: Respondents’ trust placed in historic sites to provide an accurate account of history. (T1)

Challenges and opportunities: Just as Rosenzweig and Thelen found over 20 years ago, the American public continues to trust museums above all other sources of the past. Similarly, fictional films and TV rank low, though their last-place ranking in Rosenzweig and Thelen has now been supplanted by social media and video games. Beyond topline results, trust in sources varies considerably as a function of age, race/ethnicity, and political leanings. Bearing in mind that trustworthiness is largely a matter of perception, educators have an enormous opportunity to get the public thinking about why some sources are considered more reliable than others, whether those assumptions are valid, and how a particular source could move up or down the trustworthiness spectrum. Greater awareness of such issues could go a long way in improving both historical knowledge and information literacy.

← Previous section Next section →