Summary: A healthy majority of respondents reported preferring unmediated learning experiences with history via direct consultations with texts and artifacts, as opposed to receiving information from an expert. The public also voiced a penchant for history that challenges extant knowledge, even though most also felt that being entertained offered learning benefits. Although there were variations by subgroups, there is more consistency than discrepancy in the survey results.

We saw in Sections 3 and 4 that respondents consulted and trusted various sources about the past to varying degrees. Moreover, frequency of source use and trust in those sources did not always align. In addition to such preferences, results revealed that the public has inclinations for how it best learns about the past. A word of caution is in order: these results reflect only preferences and are thus indirect measures of what or how well people actually learn. Direct measures of learning would consist of ascertaining what exactly people learned and how well they learned it, which was beyond the scope of our poll but is common in classroom assessments. Moreover, it is well documented in metacognition studies that people, especially nonexperts in a discipline, tend to inaccurately estimate their own knowledge and abilities in that field. (See the chapter by John Girash in Applying Science of Learning in Education for an overview.)

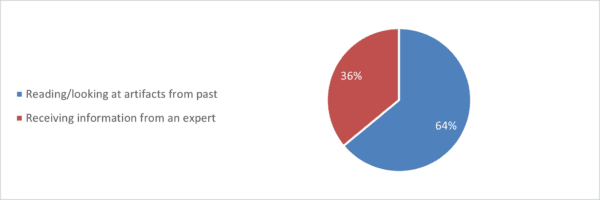

That said, respondents indicated they preferred to encounter history on its own terms and to actively investigate it, rather than passively receive it. This is reflected in the 64 percent who wanted to learn by reading or looking at historical documents and artifacts, as opposed to the 36 percent who desired to obtain information from an expert (Figure 46). How well those results would hold up in practice, especially when learners encountered ambivalent, confusing, or even contradictory readings and evidence, is debatable: direct measures are warranted to tease out such things. Survey results here, as elsewhere, may be more aspirational than reflective of reality.

Figure 46: Survey respondents’ preferred mode of learning about the past. (T2)

Figure 46: Survey respondents’ preferred mode of learning about the past. (T2)

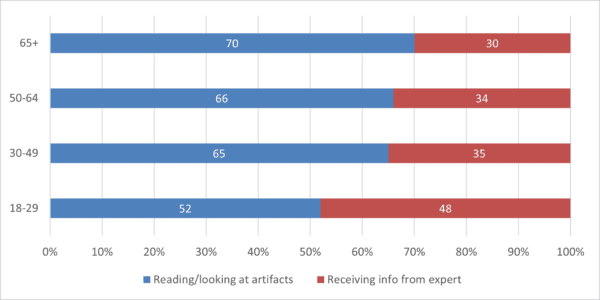

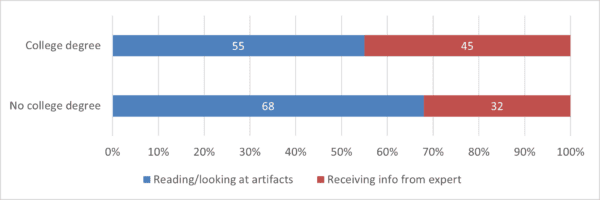

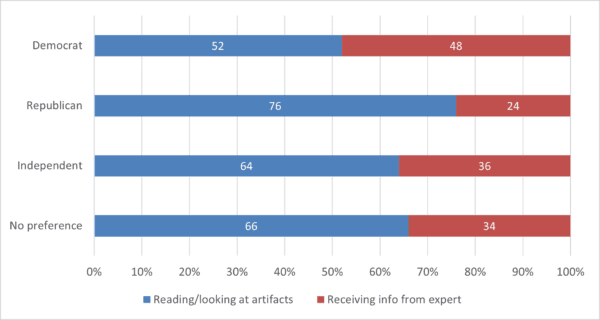

Differences in attitudes in how best to encounter the past crop up in cross-tabulations. Our survey results suggest that younger respondents have a striking level of faith in, and engagement with, the apparent authenticity of physical objects and primary documents, as opposed to the authority of the teacher as intermediary (Figure 47), a finding with obvious ramifications for classroom approaches. Curiously, those with a college degree were considerably more likely to prefer expert interpretations of the past, relative to their non–college degree counterparts (Figure 48). (This is possibly explained by college graduates’ prolonged exposure to professors, who were highly trusted to accurately convey the past; see Figure 26 above.) The other notable outlier here was party identification, where Republicans voiced preferences by at least 10 points over other groups to eschew expert interpretations of the past (Figure 49).

Figure 47: By age group: Respondents’ preferred method to learn about the past. (T2)

Figure 47: By age group: Respondents’ preferred method to learn about the past. (T2)

Figure 48: By education level: Respondents’ preferred method to learn about the past. (T2)

Figure 48: By education level: Respondents’ preferred method to learn about the past. (T2)

Figure 49: By political party: Respondents’ preferred method to learn about the past. (T2)

Figure 49: By political party: Respondents’ preferred method to learn about the past. (T2)

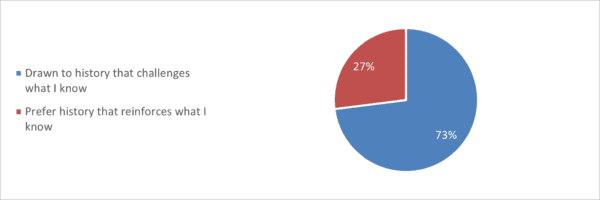

Delving into history by independently reading and looking at artifacts from the past inevitably confronts learners with challenges, even contradictions, to preconceived notions. How did respondents report dealing with such dissonance? A clear majority of those surveyed indicated a preference for history that challenges their understandings as opposed to confirming any knowledge they might already possess (Figure 50; compare with Figure 136). We should be very cautious with such results since respondents could be ascribing a fairmindedness to themselves that does not materialize in practice. Indeed, recent studies of Americans’ information gathering habits reveal a population that increasingly self-selects (or is pushed by sophisticated computer algorithms) into knowledge-affirming partisan camps.

Figure 50: Survey respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. (V9)

Figure 50: Survey respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. (V9)

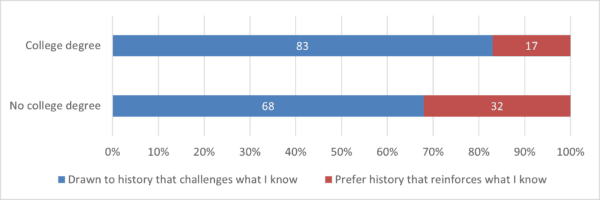

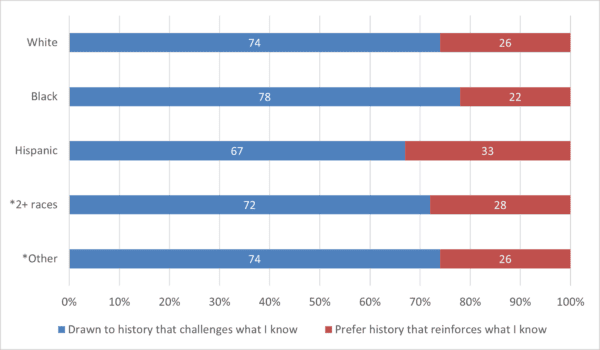

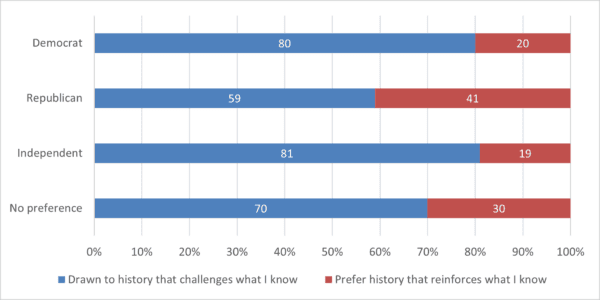

Although a majority of all demographic groups reported a preference for challenges to their extant historical knowledge, some notable differences did occur. Those without a college degree were nearly twice as likely than degree holders to prefer familiar over challenging history (Figure 51). The cautionary note in the previous paragraph notwithstanding, such data might underscore the value of college education in opening minds to new ideas. Hispanics were more prone to favor reinforcing history (33 percent) than were whites (26 percent) or Blacks (22 percent) (Figure 52). Political affiliations resulted in especially wide fault lines, with Republicans being more than twice as likely to prefer familiar historical information (41 percent) than were Democrats (20 percent) and independents (19 percent), while those with no party preference fell in between (Figure 53).

Figure 51: By education level: Respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. (V9)

Figure 51: By education level: Respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. (V9)

Figure 52: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V9)

Figure 52: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V9)

Figure 53: By political party: Respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. (V9)

Figure 53: By political party: Respondents’ preference for history that challenges or reinforces extant knowledge. (V9)

We also measured the perceived role of entertainment in the learning process. A great majority of respondents (73 percent) felt that it was easier to learn history when it was presented as entertainment, a perception that helps explain some of the public’s preferred sources of the past (Figure 14). A healthy majority of all demographic groups maintained this view in the cross-tabulations. Yet, we note that it is easy to conflate entertainment with learning, especially in the minds of nonexperts. Cognitive psychologists have shown that the act of learning is actually quite difficult and is not “fun” or some cognate thereof. Finally, we note that sources of the past geared toward entertainment, such as fictional films/TV and video games, garnered little trust in the public’s mind (Figure 26). A certain amount of cognitive dissonance seems to be on display.

Readers should thus exercise considerable caution when drawing conclusions from these data. Learning preferences and actual results are not necessarily congruent. Even the public’s own survey responses hint at this, as when the sources respondents reported turning to most frequently were often not the same ones perceived as conveying reliable information about the past.

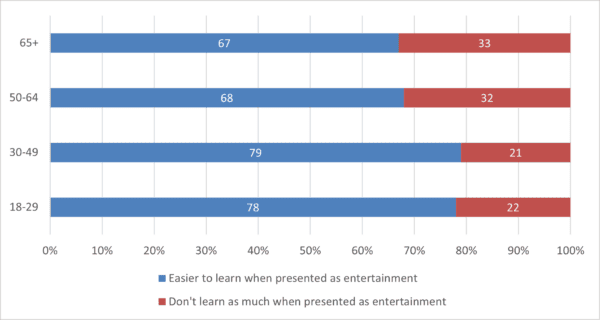

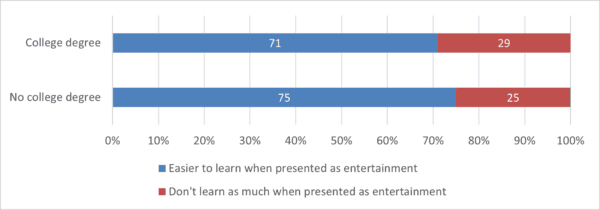

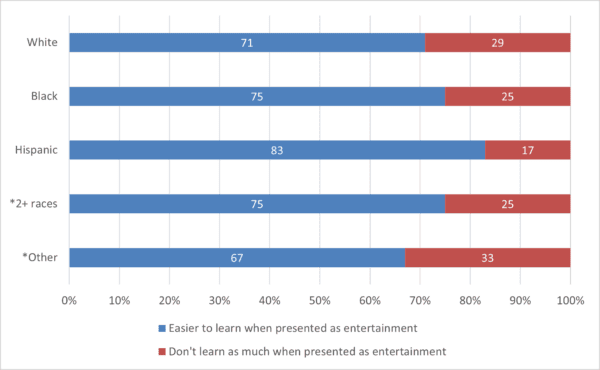

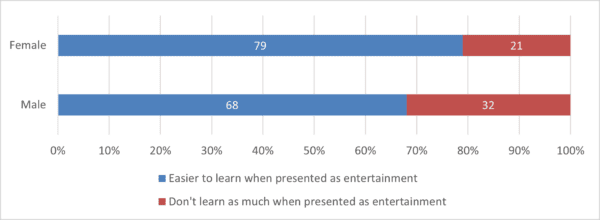

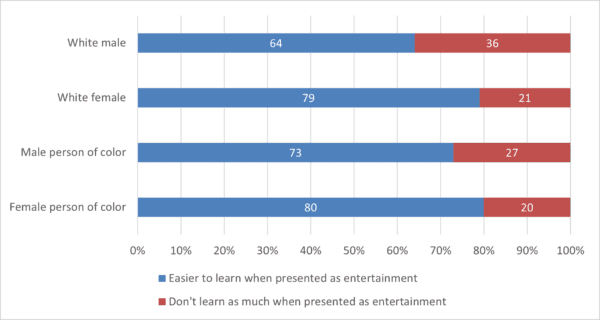

Younger respondents were more likely than older ones to voice a predilection for entertainment in the history learning process (Figure 54), but the acquisition of a college degree had little effect on this preference (Figure 55). Hispanics voiced the most support for entertainment, with Blacks’ and whites’ attitudes steadily diminishing on the issue (Figure 56). Women surpassed men by 11 points in the value placed on entertainment (Figure 57), a correlation that held to greater or lesser degrees when broken down by gender, race, and ethnicity (Figure 58). Differences by political party or region of the country were token.

Figure 54: By age group: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 54: By age group: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 55: By education level: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 55: By education level: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 56: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V6)

Figure 56: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V6)

Figure 57: By gender: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 57: By gender: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 58: By gender/race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Figure 58: By gender/race/ethnicity: Respondents’ views on the role of entertainment in the history learning process. (V6)

Challenges and opportunities: It is understandable, even heartening, that the public wants to commune directly with the past, and that people seem so willing to have their knowledge and beliefs challenged. Yet, there is reason for skepticism. Developing the skills to examine historical texts and artifacts is hard work and, while intellectually satisfying, is rarely entertaining. Accommodating new and discordant information is likewise difficult. Utilizing commonly consulted sources of the past such as documentary and fictional films and TV—sources that usually include an entertainment component—as vehicles to help teach the past is just one way to possibly square this circle.

← Previous section Next section →