Summary: The supposed inutility of a history degree has become a cliché, reinforced by declining history enrollment figures on college campuses. Despite that, respondents voiced strong support for the importance of learning about the past, even relative to ostensibly more practical fields—a trend that held across demographic groups. What is lacking, survey results indicate, is historians’ adequate treatment of certain peoples and topics, while others garner too much attention.

It is impossible not to use history in some way as we go through our daily lives, even if that use is only rudimentary or subconscious. But such frequent usage does not necessarily translate to perceived value, as we saw in the cases of historical source utilization (Section 3), trust in sources (Section 4), and the ability of those sources to generate interest in the past (Section 7). To employ a comparison, most Americans utilize numbers and basic mathematics every day, but this does not mean that the country is awash in math lovers.

But while STEM disciplines are seeing steady or even increasing interest at the college level, history numbers, measured both by numbers of majors and enrollments, have slid downward since a high point around 2012. As of this writing, history course enrollments and majors appear to have bottomed out and are even rising at some institutions. But the numbers are still lower than they were a decade ago. Using those figures as a proxy for society’s value in the field is a grim calculus.

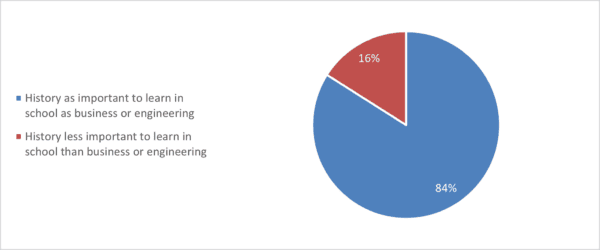

We employed a blunt-force survey question to measure people’s value of history. However, simply asking whether they felt the field was valuable or not is a “costless choice,” insofar as there would be no downside in answering in the affirmative. Instead, we inquired whether respondents felt it was equally or less valuable to learn about the past than about the more popular and seemingly more useful fields of business and engineering.

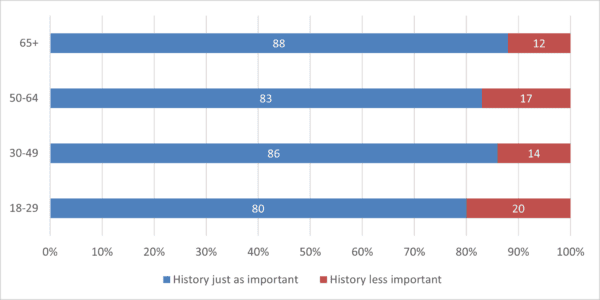

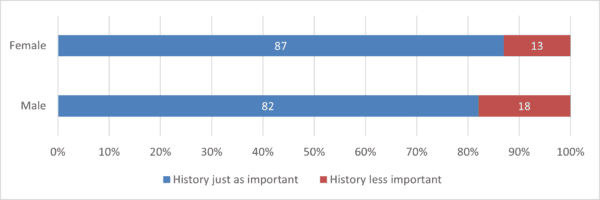

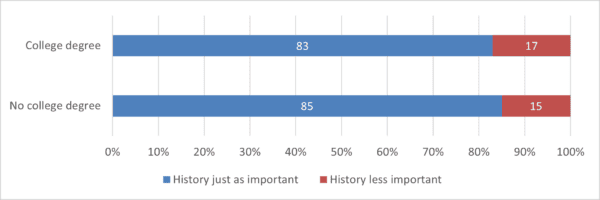

The results were inconsistent with college enrollment figures, as 84 percent of respondents said that history education is just as important as those two professional fields (Figure 86). That result held fairly steady across age groups (Figure 87), genders (Figure 88), education levels (Figure 89), races and ethnicities (Figure 90), political party affiliations (Figure 91), and regions of the country (Figure 92). If the public indeed sees such parity between programs, it is not voting with its feet that way on college campuses.

Figure 86: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 86: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 87: By age group: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 87: By age group: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 88: By gender: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 88: By gender: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 89: By education level: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 89: By education level: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

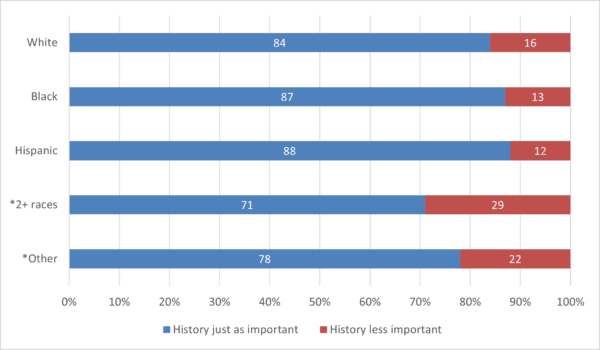

Figure 90: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V8)

Figure 90: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V8)

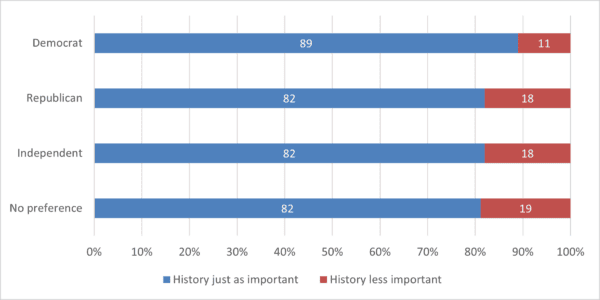

Figure 91: By political party: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 91: By political party: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

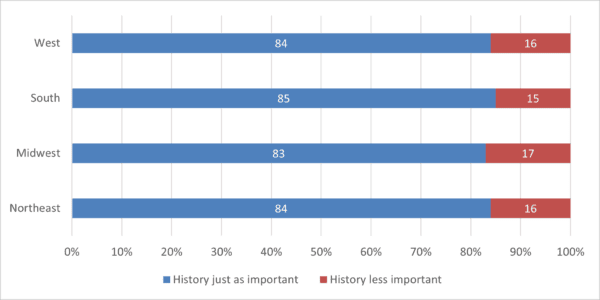

Figure 92: By region: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Figure 92: By region: Respondents’ perceived value of learning history compared with business or engineering. (V8)

Another way of measuring the value that the public attaches to history was to ask whether historians were perceived as paying adequate attention to various issues. In other words, do historians serve the needs of society in terms of the information they produce?

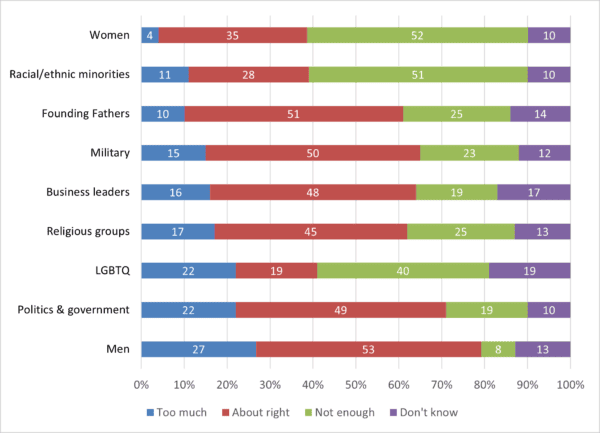

To answer that question, we gave survey-takers nine historical subjects and asked if historians seem to give them sufficient consideration (Figure 93). It is important to note that these responses track public perceptions rather than reflect historians’ actual efforts put toward these areas of the past. Yet, the results give insights on which topics respondents believe are underserved by historians.

At the two poles were the subjects of men and women: the former, indicated respondents, garner too much attention, while the latter, not enough. The safely traditional topic of politics and government ranked second in receiving an excess of historians’ time, but was tied with the more progressive subject of LGBTQ history. This is where turning to measurements of “about the right amount” of treatment is instructive. The topics of the Founding Fathers, the military, and men—all mainstream by most standards—reached 50 percent or higher in terms of adequate treatment. Meanwhile, LGBTQ’s last-place ranking for sufficient attention (19 percent) is joined by racial and ethnic minorities (28 percent) and women (35 percent) as historical subjects that have struggled for greater recognition. This is reinforced by the latter three topics’ leading rankings as areas needing more attention from professionals. The dissonant stance of LGBTQ history as a subject perceived as receiving both too much and not enough treatment, and with the fewest respondents voicing sufficient attention, seems to show it as a polarizing subfield in today’s society.

Figure 93: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to various subjects by historians. (V18)

Figure 93: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to various subjects by historians. (V18)

A final observation about the data in Figure 93 is that perceptions of not enough attention (reaching as high as 52 percent) greatly outweighed those of too much (topping out at only 27 percent). And while three topics were perceived as receiving adequate treatment in the minds of at least half of respondents, six subfields failed to reach majority consensus. The overall picture is thus one where historians are seen as coming up short in dealing with many subjects that matter most to the public.

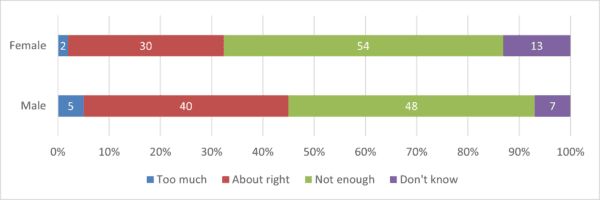

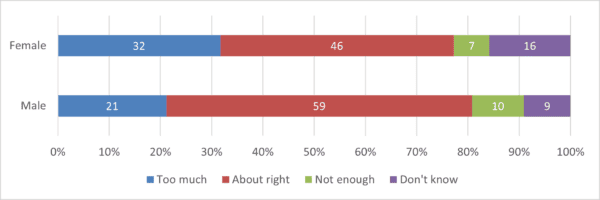

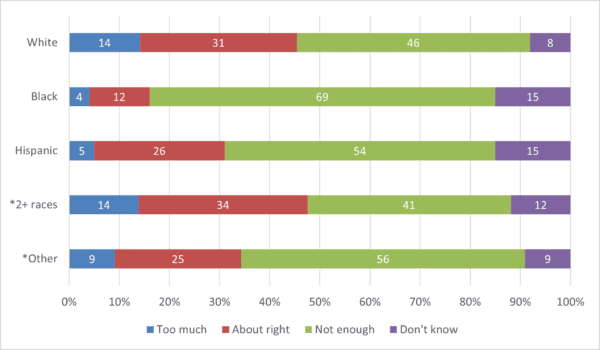

A key component to addressing this deficit, and therefore to augmenting history’s value in the public eye, is to recognize the dissimilar views of various demographics on these issues. Although it is assumed that survey-takers answer questions dispassionately, it is sometimes hard not to see dissatisfaction, even frustration, in their responses about the attention paid to some subgroups and topics by historians. The consideration given to women was seen as clearly lacking overall, but female respondents gave evidence of feeling especially shortchanged (Figure 94; curiously, we note that 13 percent of female survey-takers did not have thoughts on the matter). Conversely, women believed that men are overstudied in history, relative to their male counterparts’ views (Figure 95). A similar dynamic emerged from Blacks, Hispanics, and other people of color when asked about historians’ work on racial and ethnic minorities (Figure 96).

Figure 94: By gender: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to women by historians. (V18)

Figure 94: By gender: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to women by historians. (V18)

Figure 95: By gender: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to men by historians. (V18)

Figure 95: By gender: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to men by historians. (V18)

Figure 96: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial and ethnic minorities by historians. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V18)

Figure 96: By race/ethnicity: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial and ethnic minorities by historians. *Fewer than 100 responses. (V18)

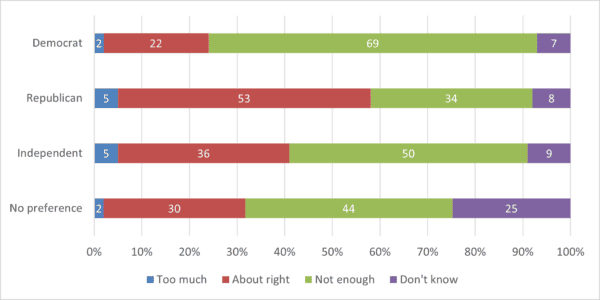

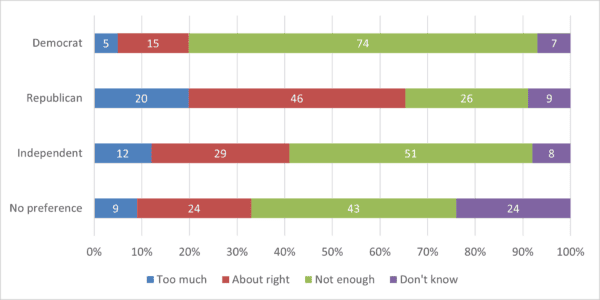

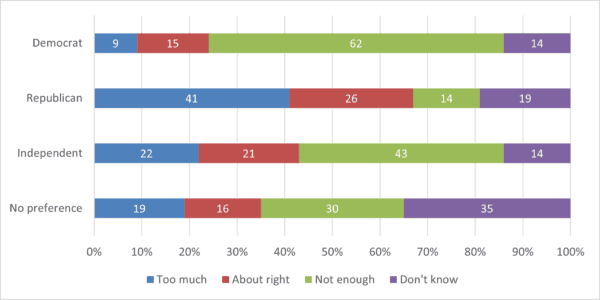

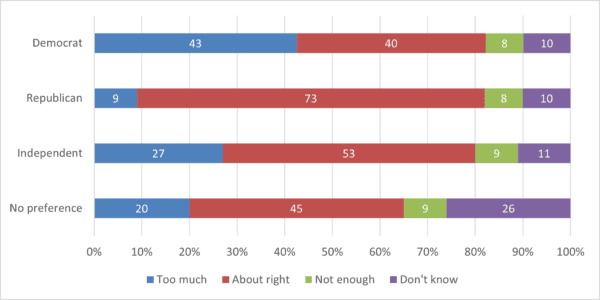

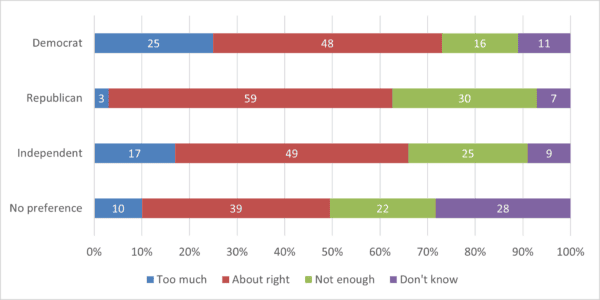

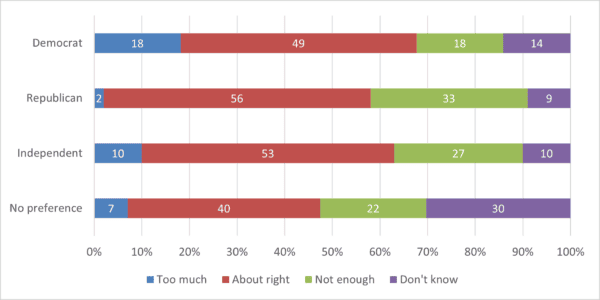

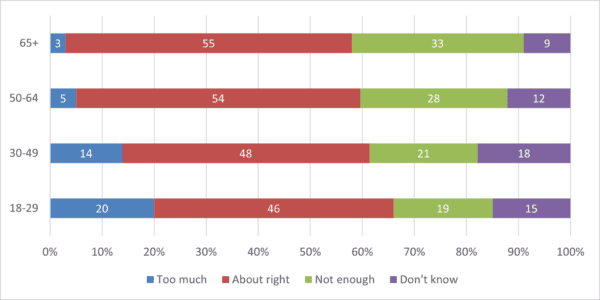

Partisanship also appeared as a wedge. Republicans were far less likely than any other party adherents to believe that women (Figure 97), ethnic/racial minorities (Figure 98), and the LGBTQ community (Figure 99) are disregarded in historical work. For their part, Democrats pointed to men (Figure 100), the military (Figure 101), and the Founding Fathers (Figure 102) as topics receiving undue consideration.

Figure 97: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to women by historians. (V18)

Figure 97: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to women by historians. (V18)

Figure 98: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial and ethnic minorities by historians. (V18)

Figure 98: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial and ethnic minorities by historians. (V18)

Figure 99: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to LGBTQ individuals by historians. (V18)

Figure 99: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to LGBTQ individuals by historians. (V18)

Figure 100: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to men by historians. (V18)

Figure 100: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to men by historians. (V18)

Figure 101: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the military by historians. (V18)

Figure 101: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the military by historians. (V18)

Figure 102: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the Founding Fathers by historians. (V18)

Figure 102: By political party: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the Founding Fathers by historians. (V18)

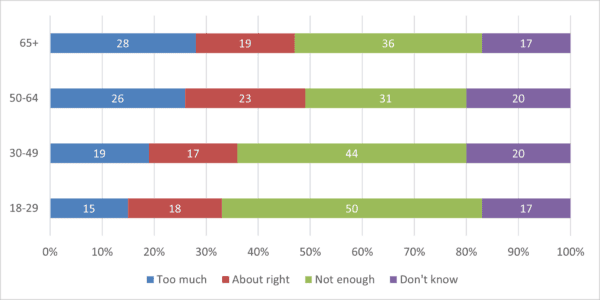

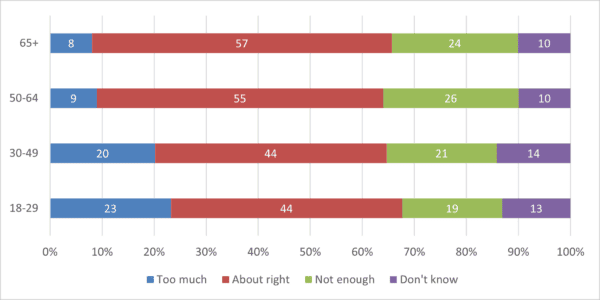

Attitudes on these matters might change for two reasons, according to survey data. One reason is age, and there are two plausible scenarios for what forces could be at work. The first runs as follows. Younger people are more tolerant of traditionally neglected groups, such as the LBGTQ community (Figure 103) and racial/ethnic minorities (Figure 104); at the same time, the youngest group are less interested in mainstream topics such as the Founding Fathers (Figure 105) and the military (Figure 106). Younger demographics then carry those values into their later years, in which case society’s principles as a whole change. Contrariwise, the data might indicate that people’s values mutate as they mature, whereby the younger cohort increasingly comes to hold beliefs that its forebears held earlier, and the cycle begins anew. This latter scenario leaves society’s opinions more or less unchanged on such historical matters. Because survey results represent a snapshot in time, and because these scenarios look only at bivariate relationships, it is hard to know which one is more on target.

Figure 103: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to LGBTQ individuals by historians. (V18)

Figure 103: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to LGBTQ individuals by historians. (V18)

Figure 104: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial and ethnic minorities by historians. (V18)

Figure 104: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial and ethnic minorities by historians. (V18)

Figure 105: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the Founding Fathers by historians. (V18)

Figure 105: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the Founding Fathers by historians. (V18)

Figure 106: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the military by historians. (V18)

Figure 106: By age group: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the military by historians. (V18)

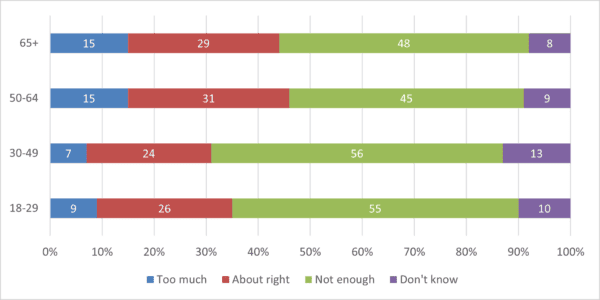

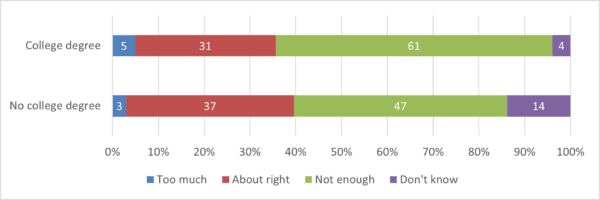

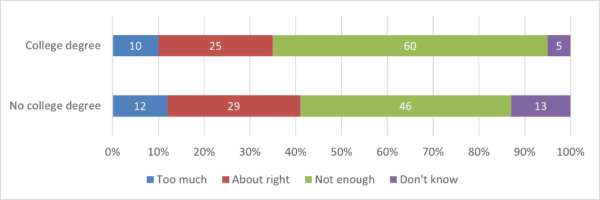

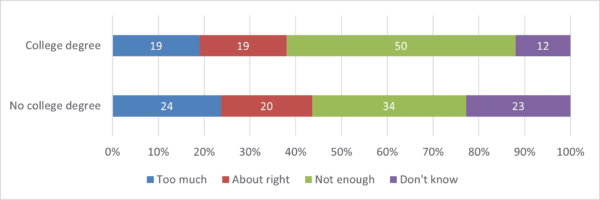

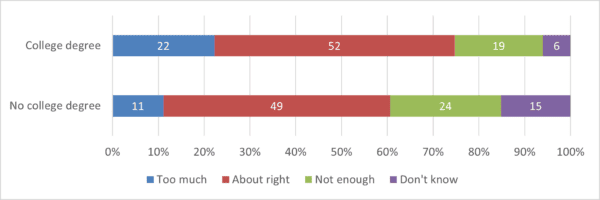

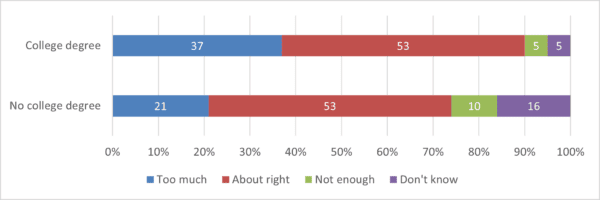

The second factor signaled in the survey data is higher education. Those with a college degree were far more likely than non–degree holders to perceive historians’ lack of treatment of women (Figure 107), racial/ethnic minorities (Figure 108), and the LGBTQ community (Figure 109); they also felt that historians give too much attention to the military (Figure 110) and men (Figure 111). Differences for other topics by education were marginal, though nondegreed respondents always registered higher “don’t know” rates, often by double digits. We cannot be sure of the reason for these discrepancies. Do college courses lead to students’ more progressive outlooks? Or are individuals with those views already in place more apt to obtain college degrees? The answer need not be strictly binary.

Figure 107: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to women by historians. (V18)

Figure 107: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to women by historians. (V18)

Figure 108: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial/ethnic minorities by historians. (V18)

Figure 108: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to racial/ethnic minorities by historians. (V18)

Figure 109: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to LGBTQ individuals by historians. (V18)

Figure 109: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to LGBTQ individuals by historians. (V18)

Figure 110: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the military by historians. (V18)

Figure 110: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to the military by historians. (V18)

Figure 111: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to men by historians. (V18)

Figure 111: By education level: Respondents’ perceptions of attention paid to men by historians. (V18)

Challenges and opportunities: Results in this section are a tale of the glass being half full and half empty. On the plus side, there is strong majority support for the central importance of learning about the past, but unfortunately, that sentiment is not translating into a better situation on college campuses. The AHA has actively promoted solutions to this issue, and it at least appears that the enrollments ship is no longer taking on water. Respondents voiced the need for historians to devote greater or less attention to a variety of subjects, but it appears that any adjustment runs the risk of alienating as many people as it assuages. Navigating this minefield is no simple task.

← Previous section Next section →