This resource was developed in 2004 as part of “The Conquest of Mexico” by Nancy Fitch.

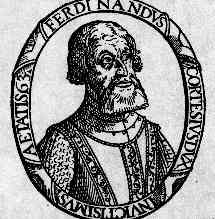

Hernan Cortés

Few historical stories are more exciting and more significant than the one about the Spanish conquest of the Mexicas, more commonly but wrongly called the Aztecs. The consequences of the conquest remain starkly evident as we approach the twenty-first century: Mexico remains a poverty-ridden, politically unstable country, where Amerindian and mestizo peasants continue to fight soldiers for land their ancestors lost centuries before they were born. Yet remarkably little is written about the conquest in major world history textbooks. Dismissed in a paragraph or two, the collapse of the Mexica Empire is written as though it were almost inevitable, a swift and decisive victory for a civilization destined to be dominant. But if one examines eye witness or near-eye witness accounts, however, a quite different picture appears. Both Spanish and Nahuatl (Mexica) sources reveal a complex struggle with a great deal of fighting and betrayal everywhere. If the conquistador, Hernán Cortés, was often calculating and ruthless, there were many times when he also believed he was fighting to stay alive. Indeed, as one textbook noted, the question which must be answered is “Why did a strong people defending its own territory succumb so quickly to a handful of Spaniards fighting in dangerous and completely unfamiliar circumstances?” The answers to this question usually include differences in military tactics and technology, disease, political and religious divisiveness within the Mexica Empire, and the weakness of the Mexica Emperor, Moctezuma Xocoyotl (II), or simply Moctezuma.

Although she has appeared in both Spanish and Mexican literary accounts of the conquest, Malinche, la lengua, Cortés’s translator and mistress, has only recently been mentioned in history texts as one of the factors which allowed Cortés to claim victory. In the words of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a Spaniard who was with Cortés during the conquest, La Malinche “knew the language of Coatzacoalcos, which is that of Mexico [Nahuatl], and she knew the Tabascan language also. This language is common to Tabasco and Yucatán [the Yucatán dialect of Mayan], and Gerónimo de Aguilar spoke it also.” (Meet Jeronimo de Aguilar.) As Bernal Díaz explained, “this was the great beginning of our conquests, and thus, praise be to God, all things prospered with us. I have made a point of telling this story, because without [La Malinche] we could not have understood the language of New Spain and Mexico.”

La Malinche is an historical figure who aided the Spaniards and gave birth to Cortés’ son, Martin, sometimes considered to be the first mestizo. But she is far more significant as a symbol for everything, both good and bad, about the conquest. In the words of Rosario Castellanos, “some call her a traitor, others consider her the foundress of our nationality. . . .” Reflecting the view of her as a traitor, a variation of her name has become the word for the individual who sells out to the foreigner: la malinchista. As the mother of Don Martín, she has been called La Chingada, the submissive one or the mother taken by force. Was she a desirable whore or a disgraced mother? Is it possible for the historian to know the truth or is her story the story of many more ordinary women, the story of woman as a powerful cultural symbol which will always remain both more and less than her historical persona? The story told here is as much about how history is written and lives to create historical memory as it is about the conquest of Mexico.

Although the conquest of Mexico is often told as a story by men for men, Malinche was not the only woman who accompanied the Spaniards. (Meet Isabel Rodriguez.) There are likely many more, as female camp followers played a crucial role in sixteenth-century warfare.

The other story to be told here is of the alliance between the Tlaxcalans and the Spaniards In fact, it is far too simple to argue that the Spaniards conquered the native population given that the Spaniards had thousands of allies from the territory, of which the Tlaxcalans were the most loyal. A fiercely dependent people, the Tlaxcalans believed that the Spaniards would help them vanquish their Mexica foes. They encourage the Spaniards to attack the Mexicas and their allies; in the end, they were as responsible as the Spaniards for the destruction of Tenochtitlan.

The Spaniards were also divided. Cortés deliberately broke orders from his immediate superior, Cuban Governor, Diego Velasquez, when he decided to conquer Mexico. From the minute he took his fateful decision, he sent men to the Spanish Emperor, Charles V, to explain the wealth of the continent and to seek support from the Emperor for his defiant action. The poor relationship between Cortés and Velasquez would also contribute to Spanish losses when war broke out between the Mexicas and the Spaniards, while Cortés fought Pánfilio de Narváez, who Velasquez sent to bring Cortés back to Cuba.

Moreover, although most textbooks end the story of the conquest of Mexico with Cortés’ unchallenged occupation of Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, the battle for Mexico was, by no means, over. Cortés lost two thirds of his men when he was forced to flee the city on June 30, 1520 after war broke out between the Mexicas and the Spaniards in his absence. He barely survived other attacks as he fled to Tlaxcala to heal and regroup. With much effort and considerable support from indigenous people who hated the Mexicas, he finally regained Tenochtitlan after a long siege that took place between May 26 and August 13, 1521. Even then, it took the Spaniards the rest of the Sixteenth Century to conquer what became New Spain and is now Mexico. Thus, one can argue that the conquest of Mexico took place in three phases. The first phase, which is most often covered in textbooks, dates from the days the Mexicas first heard of strangers on their eastern shores, which they thought might be their gods returning. It ended with the peaceful occupation of Tenochtitlan. The second phase began with the Spanish slaughter of innocents during the festival of Huitzilopochtli, which led to the rebellion that forced the Spaniards to flee the Mexica capital. This phase ended with the final fall and destruction of Tenochtitlan. Since the sources I am working with cover these two phases and not the larger conquest, they will be the ones covered here. To sort out what happened, you can go to the primary sources on the conquest of Mexico.