This resource was developed as part of the AHA’s Teaching Things project.

Materials

- Amphora ID cards (download as a PDF)

- Empty food containers with packaging intact (for example, yogurt, butter, jam jars, etc.)

Introduction

This object lesson explores the trade, transport, perceived value, and authenticity of ancient and modern food products. Students will investigate this history through the analysis of the containers in which food products were transported and stored within the context of the societies and cultures that produced them. The lesson centers large ceramic containers called transport amphorae, which were the primary means of packaging and transporting foodstuffs in the ancient Mediterranean and surrounding regions.

In the first part of the lesson, students will consider how the distinctive appearances of different types of transport amphorae could act as guarantees, or authenticators, for the type and value of the goods within and how the packaging of modern food products compares.

In the second part of the lesson, students will think about the recycling and reuse of both transport amphorae and modern objects related to the production and distribution of food. Students will explore how the lifespans and many uses of these objects affected the values of both the containers and their contents. At the end of this lesson, students should be able to identify distinctive characteristics of ancient and modern food packaging that convey messages to consumers, articulate these messages, and contextualize them within their respective cultures.

Part I

Ancient Food Packaging and Transportation

Throughout antiquity, transport amphorae were widely distributed around the Mediterranean and beyond. Amphora advertised their contents with their distinctive shapes and (occasionally) stamped handles and/or pictographs, communicating if they contained wine, olive oil, fish sauces, or other foodstuffs. They were recognizable to a wide and diverse set of merchants and consumers. In other words, these containers served as guarantees of their contents to merchants and consumers in markets far beyond where they were produced.

Ancient Greek and Roman literary sources contain references to the quality of certain products and their containers. For example, in Aristophanes’s comedic play, Ecclesiazusae (lines 1112–1124), a character praises the sweet taste of wine from Thasos (an island in the Aegean Sea) and blesses the Thasian amphorae in which the wine was packaged.

Classroom Activity: Close Analysis of Ancient Transport Amphorae

ID cards are provided below, but instructors can identify additional examples.

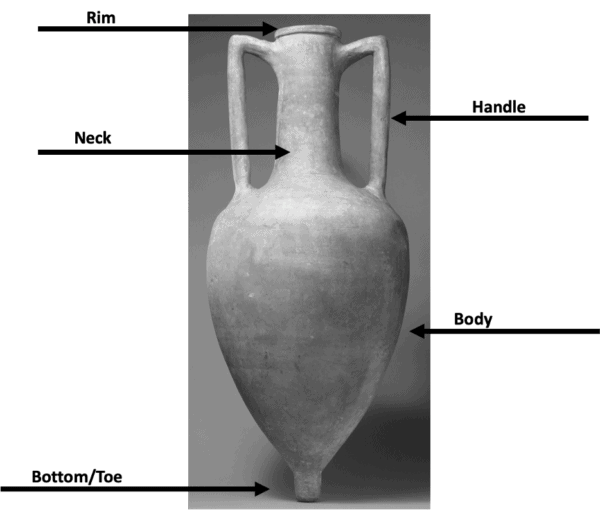

Write a description of your amphora.

- What do you think it is made from? What color is the material?

- Is the bottom flat or pointed? Does it have a “toe”/peg? Why do you think the bottom is shaped as it is?

- What shape is the body? Is it long and slender or round? Is one part wider than another?

- What does the neck look like? Is it wide or thin? Is it long or short? Does it taper or remain a consistent width?

- What shape is the rim? Is it round or triangular? Thick or thin?

- What do the handles look like? Where do they attach to the body? Are they circular or flat? Are they round or angular?

- Describe any other features you see (including stamps, pictographs, etc.)

Consider the information about your amphora’s place of production, original contents, and distribution.

- What contents did your amphora type typically contain?

- Does anything about the shape of your amphora make it conducive for carrying these contents?

- How widely was your amphora type distributed in antiquity? Where is it most common?

- Is there anything surprising about its distribution patterns?

- How does your amphora type compare to other amphorae in terms of shape, contents, and distribution?

- How would consumers recognize your amphora type and the goods it contained?

- What else would you like to know about your amphora and the others? How could you find out this information?

Modern Food Packaging

Like ancient transport amphorae, modern food packaging is often distinctive to consumers. Their shapes, materials, and logos work together to advertise and authenticate their contents on store shelves. And like ancient foodstuffs, modern food products can have expansive distribution patterns that bridge different cultures and traditions.

Classroom Activity: Close Analysis of Modern Food Packaging

Provide students with pictures or physical examples of food containers in a variety of shapes and materials and cards with basic description of their distribution. You might use cereal boxes, yogurt containers, or condiment packages.

Write a description of your food package.

- What is the shape? Is there anything unique or distinctive about the shape?

- What is the package made of?

- What does the label look like? What colors are used?

- What information is easiest to see? What information is difficult to see?

Consider the information about the distribution of your product

- How accessible is this product to different sets of consumers?

- What about the packaging advertises or distinguishes the product inside?

How does your product’s packaging compare to others? How would consumers recognize it?

Why do you think your food package looks the way it does? Do any aspects of it make it easier to ship or store? To preserve food?

Classroom Discussion: Comparison of ancient and modern

- How do transport amphorae and modern food packages advertise their contents to consumers?

- What are the similarities and differences?

- What can we learn from the transport amphorae and modern food packaging about who was purchasing the products originally contained in them?

- How would ancient consumers be guaranteed that the goods they were purchasing in transport amphorae were authentic?

- How does that compare to modern consumers and the products in modern food packaging?

- What are some similarities and differences in the distribution patterns of transport amphorae and the modern containers?

- What does this tell us about the accessibility of ancient and modern foodstuffs?

- Compare the shapes and sizes of the transport amphorae and the modern containers. How are they similar and different?

- What are some reasons that could explain these similarities and differences?

- How are the materials from which transport amphorae and modern food packaging are made different and similar?

- What does this tell us about how they were produced and their value to consumers?

- What other observations do you have about the similarities and differences between transport amphorae and modern food packaging?

Part II

Life Cycles of Ancient Amphorae

In addition to the (often) expensive products they transported, amphorae themselves were valuable. Their production was an involved and lengthy process, as they were large, heavy, and required the preparation of large amounts of raw materials to create them. Expert potters shaped, assembled, and fired them in a special oven for making pottery, called a kiln, without destroying or damaging them. The investment of labor and materials meant that transport amphorae were reused multiple times. While goods arrived at a market in transport amphorae, the individuals who purchased the product usually took smaller amounts home in other containers like wineskins (typically made from animal skin, like that of a goat) or smaller ceramic vessels such as pitchers and small jars. The amphora remained at the market until its entire contents had been sold. When emptied, it might then be put back into circulation, refilled with other contents.

When transport amphorae became too damaged to be used for the transport of products or were too far removed from their original trade networks, they were recycled for other purposes. Ancient Greek and Roman literary sources are full of references to amphorae that were recycled for various purposes. Sometimes they were used for storing different food products in commercial contexts. For example, Pliny the Elder wrote that wine from Terracina is best when stored in amphorae from Surrentum (NH 14.4). Herodotus also described the reuse of Greek and Phoenician wine amphorae that had been imported to Egypt—administrators collected empty ones and transported them to Memphis, where they were filled with water to be transported to Syria (Hist. 3.6.2).

Aside from mention in textual sources, transport amphorae are often excavated in domestic, or household, contexts, typically among large storage-type vessels called pithoi in Greece and dolia in Rome. These archaeological findings suggest that transport amphorae were repurposed and used by private individuals as storage containers in their homes. There are also numerous examples of broken amphorae sherds used in construction as filling pieces in the Roman period. When constructing buildings from concrete, Roman architects used large broken pieces of pottery to help bind and set the concrete. The robustness of amphora pieces made them ideal for construction. When an amphora was no longer useful, even in a recycled context, it was likely dumped into a garbage pit. One dump in Rome, specifically used for transport amphorae, was so large it created an artificial mound that can still be viewed today, called Monte Testaccio.

Life Cycles of Modern Food Packages

Modern food packaging containers are typically mass produced, made from materials like cardboard, plastic, and glass, and are smaller, lighter, and therefore more portable than ancient transport amphorae. In addition, modern industrial innovations and techniques in the production of these packages mean that they are created easily, cheaply, and quickly, unlike transport amphorae.

Modern food containers are usually purchased by individual consumers in a store and then brought into a household context, where they typically act as storage containers until their original products are completely consumed. After they are emptied, they might be repurposed—perhaps to store other foodstuffs or objects, or in household or art projects—or sent to a recycling facility where they are made into new materials. They might also be discarded in the trash.

Object Life Cycles & Biographies

The packages of foodstuffs, ancient and modern, had their own kind of “life cycles” during which they served different purposes and were valued differently. The life cycle of a typical transport amphora might include production/creation, several cycles of transport, repurposing or recycling, and destruction/abandonment. Of course, not all transport amphorae had the same type of “life.” Some amphorae ended up at the bottom of the sea, having been the cargo of a shipwrecked vessel, while others were recycled once again, this time as museum displays after being excavated by archaeologists, and analyzed, categorized, and preserved by museum conservators.

Throughout the stages of a transport amphora’s life, it would likely be valued differently by the person using it for their own purposes. For example, while an object for transport, the amphora’s high value as both an expensive object to produce and a guarantee of the products transported within it was assigned by the people who created it and the products and the merchants who sold the products within. As the amphora went through several cycles of transport and became too worn or broken to continue as a transport vessel, its value to the producers and merchants would decrease. In its next stage of life, perhaps as a storage vessel, the amphora would be valued by the individual was using it in its new capacity, and so on, until it was abandoned and lost, as in most cases, or was preserved and became a high value object in a museum display. The story of a transport amphora’s life stages and changing value associated with each stage is what comprises an object’s “biography.”

Modern food containers, too, have life cycles that include production/creation, transport, possible recycling, and destruction/abandonment. Their value also changes over the course of their life cycles, and, with the combination of their life stages and respective values, we can write object biographies for them in the same way we can for ancient transport amphorae.

Egg cartons, for example, are mass produced for the transport and storage of eggs to grocery stores, where they are purchased and transported to the homes of consumers. Yet they do not have significant monetary value. Usually, egg cartons are discarded after one use, having no value at all. However, egg cartons might be recycled by individuals who have chickens of their own for the storage and sharing of the eggs their chickens produced. In this case, the carton still has value, though minimal economic value. Egg cartons might also be recycled for art projects or in other similar contexts, cases in which they might have much more value than in their original use, even if that value is sentimental. Other objects, such as those made of plastic or glass, might be recycled several times for the storage of leftover meals or displayed as prestige objects if their original contents were expensive. All of these scenarios are part of a given object’s biography.

Classroom Discussion: Object Biographies

- How do the physical characteristics (such as size, shape, and materials) of transport amphorae and modern food packaging affect their respective life cycles and object biographies?

- Think back to how the physical properties of these objects served as guarantees for the products they contained.

- How do their respective values compare at various stages in their life cycles?

- Is one more valuable than the other overall? Does it depend on the stage of their life cycle?

- Write an object biography for your transport amphora and your modern food container.

- How are they similar? How are they different?

- What do the object biographies of your ancient and modern containers tell you about the cultures and societies that produced them?

Additional Reading and Resources

University of Southampton Amphora Database

Database of references to amphorae in ancient Greek sources

Article on Monte Testaccio from Archaeology Magazine

Open-source copy of Pliny’s Natural Histories (he has several chapters discussing specific types of wine and food products, text has a word search option)

The following articles examine amphorae production and distribution. Instructors may wish to assign sections on production, transport, etc.

- Gallimore, Scott. “Amphora Production in the Roman World: A View from the Papyri,” Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 47 (2010): 155–84.

- Investigates evidence for amphora production and distribution in ancient papyri

- Peña, Theodore J. and McCallum, Myles. “The Production and Distribution of Pottery at Pompeii: A Review of the Evidence; Part 2, the Material Basis for Production and Distribution,” American Journal of Archaeology 113, no. 2 (April 2009): 165–201.

- [Note especially pps. 190–92 on facilities for packaging and bottling of wine and fish products in Dressel 2-4 style amphora in the Bay of Naples region.]

Amphora ID Cards

Download the ID cards as a PDF.

(All information, unless otherwise noted, is sourced from: University of Southampton, Roman Amphorae: a digital resource [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service. 2014. https://doi.org/10.5284/1028192)

Related Resources

June 11, 2025

History of Tariffs

April 7, 2025

History of the Federal Civil Service

March 13, 2025