About GI Roundtable Series

The GI pamphlet series was prepared under the direction of the Army’s Division of Information and Education between 1943 and 1945 “to increase the effectiveness of the soldiers and officers as fighters during the war and as citizens after the war.” Please note that while the Association oversaw the original publication of these booklets, any opinions expressed only reflect the views of their respective authors.

Introduction and Background

The great appeal of history is its ability to surprise and challenge what we think we know. Online publication of the GI booklet series of the American Historical Association provides just this sort of appeal, as it forces us to rethink the hard and fast divisions historians and the general public typically make about the 20th century.

Constructing a Postwar World: Background and Context

Between 1943 and 1946 the American Historical Association (AHA) produced a curious series of 42 pamphlets for the War Department, intended to foster discussion among GIs. What were the military imperatives that drove their creation and what cultural forms of the day were simply taken for granted by the “objective” historians and social scientists who authored the booklets?

Pamphlets

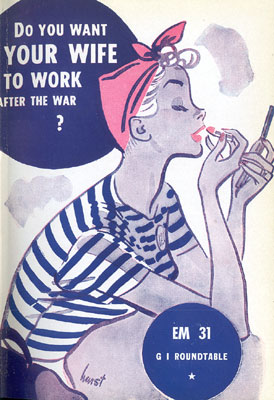

The pamphlets were intended to foster discussion among GIs on topics ranging from “Do You Want Your Wife to Work after the War?” to “What Shall Be Done with Germany?” to “What Is Propaganda?”