By Catherine Porter

Office of War Information, formerly with Institute for Pacific Relations

(Published April 1945)

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

When Did Philippine History Begin?

How Did America Enter the Picture?

What Was the Independence Act?

Is It a Democratic Government?

Introduction

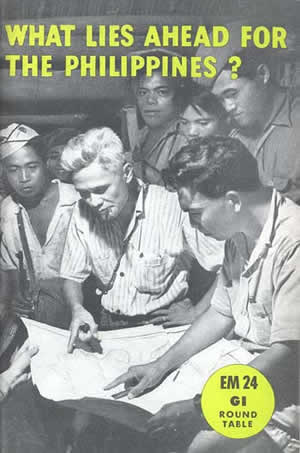

In the first months of the Pacific war, this generation of Americans heard more about the Philippines than they ever had heard before. By the spring of 1942, Bataan and Corregidor had become household words. Thousands of American soldiers were fighting and dying there side by side with thousands of Filipinos, all under General Douglas MacArthur.

Why were Americans fighting in the Philippines? How did they happen to be there when the Japanese struck? Weren’t the Philippines practically a free country? Why were we still responsible for their protection? Are we still responsible now that we have chased the Japs out? For how long? Do the Philippines want our protection? Against whom?

The answers to these questions are important, not so much for our understanding of the past as for our understanding of future problems in the Philippines. We still have responsibilities there, responsibilities which have been increased by the war. Americans have a reputation in the Philippines for keeping their word. We must fulfill those obligations with full understanding of what is involved.

What happens in the Philippines hereafter is bound to affect us more closely than have past events. It is also likely to influence the future of millions of persons who have been watching the Philippines with anxious eyes. The other dependent peoples of the Far East have seen in our record in the Philippines a glimmer of hope for themselves. They are eager to see what the outcome of that experiment will be. And other colonial powers fear lest independence for the Philippines might arouse hopes in other areas and spell eventual chaos.

Our Philippine problem, then, is not ended. The Filipinos met the test in 1941 bravely and loyally. The majority have continued to keep faith during the long bitter months and years of Japanese occupation. Now that Philippine liberation is no longer just a dim hope, relations with the Philippines are once more approaching a crucial test.

How that test is met depends in large measure upon the American people and their government.

Related Resources

September 7, 2024

Travel and Trade in Later Medieval Africa

September 6, 2024

Sacred Cloth: Silk in Medieval Western Europe

September 5, 2024