Awards & Grants

AHA Research Grants

Each year, the American Historical Association awards several research grants with the aim of advancing the study and exploration of history in a variety of subject areas. See details about the eligibility and application process for each grant on our website. The deadline for research grant applications is February 15. Open to AHA members only.

Awards for Publications

These prizes honor exceptional books, articles, films, and digital works on a wide range of historical topics.

Awards for Scholarly and Professional Distinction

These awards recognize individuals and groups who have made distinguished contributions to the discipline of history.

Professional & Career Resources

Advance Your Career

As the leading professional association for historians in the United States, the AHA serves as a hub for information on jobs, careers, and employment in the historical discipline. The AHA provides guidance, information, and job listings for historians in all stages of their careers.

Where Historians Work

Where Historians Work is an interactive, online database that catalogs the career outcomes of historians who earned PhDs at universities in the United States from 2004 to 2017.

Career Paths

Read articles by historians about their career paths in Perspectives on History.

Reviewers in Digital History

The AHA can connect you to digital historians who can assist with tenure and promotion cases that involve review of digital history projects. Contact Alexandra Levy, director of communications & public affairs, for assistance finding an appropriate reviewer.

Academic Department Resources

History department chairs are on the front lines of the discipline, defending historians’ work and supporting their professional lives at all stages of their academic careers. The AHA strives to strengthen this work and provide resources and opportunities that make chairs’ work easier and valued.

AHA Career Center

Whether you’re looking to find a job or to advertise a position, the AHA Career Center is the go-to hub for connecting with history professionals.

Resources for the Discipline

AHA Community Action and Resource Exchange

The AHA’s Community Action and Resource Exchange (CARE) program brings historians together to discuss shared professional issues and concerns, exchange ideas, and collaborate on strategies and solutions that strengthen the discipline. CARE is composed of working groups organized to discuss and share ideas, resources, and guidance to issues or concerns of professional interest to historians. CARE groups are select, member-organized, and member-led.

Standards & Guidelines for the Discipline

The AHA has developed a series of best practices for excellence in professional behavior, research, and teaching.

Digital History Resources

The AHA offers resources on getting started in digital history, articles on doing digital history, and projects of interest.

Coalitions

Cross-disciplinary coalitions that provide greater access to networks, leadership, and resources that support the AHA’s mission.

Data on the Historical Discipline

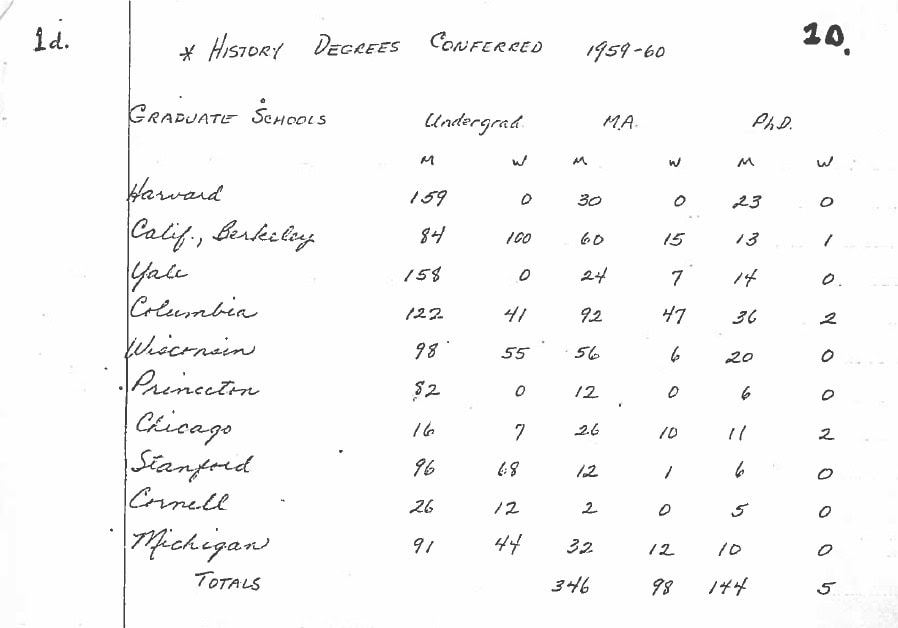

Data on the Historical Discipline

The AHA collects and shares data on topics ranging from employment, to public engagement with history, to the use of educational resources in the classroom, and more.

AHA Surveys: Historians Teaching Off the Tenure Track

The AHA's Surveys: Historians Teaching Off the Tenure Track are now closed to responses. The AHA will share a report with the results of the surveys later in 2025.

Discover Historians and History Programs

Create Connections

AHA Communities

Members can communicate and collaborate with other historians in this online networking platform.

Our Career Contacts program arranges informational interviews between current PhD and history PhDs who have built careers beyond the professoriate.

Follow the AHA on social media platforms to stay up-to-date with our latest news and activities.

Affiliated Societies

Over 125 history-oriented organizations are affiliated with the AHA, representing a broad network of organizations promoting collaboration and communication across the history community.

Member News

To recognize our talented and eclectic membership, the AHA features a regular Member Spotlight series.

Institutional & Student Memberships

The AHA is committed to helping leaders navigate the challenges facing the discipline of history at colleges and universities, as well as in libraries, archives, and K–12 schools. Institutional members can purchase discounted student memberships for only $30 each.

Upcoming Opportunities

Calls for Opportunities Calendar

The AHA’s Calls for Opportunities Calendar shares upcoming calls for papers, conference proposals, and other activities. Anyone may submit opportunities of interest to historians to the calendar.