This resource was developed as part of the AHA’s Globalizing the US History Survey project.

By Allison Frickert-Murashige (Mt. San Antonio Coll.)

The Little Ice Age, also known as “Long-Term Climate Change”

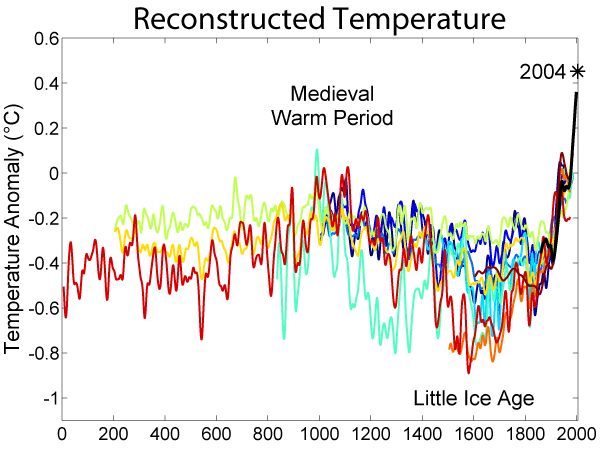

There is no more relevant example of environmental history’s relevance to human history than the so called “Little Ice Age” (LIA), a term which applies much more aptly to the Northern Hemisphere and especially Europe, as “ice age” isn’t very helpful when we are talking about drought conditions in the tropics. I like to think of this era more neutrally, both latitudinally and hemispherically, as one of “long-term climate change.”

2000 Year Temperature Comparison. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Commons

There are notable climate impacts globally with decreased temperatures and increased droughts across the era of 1200–1900, with particularly dramatic nadirs marking the “14th Century Crisis” and the “17th Century General Crisis.” These events are useful starting points for considering environmental history in the classroom. However, local circumstances and variability of climate are also important in considering the case of the globalized Little Ice Age as a meaningful and analytical tool in various regions.

Recommended Readings

- K. Jan Oosthoek, “Little Ice Age,” Environmental History Resources, June 5, 2015.

- Scott A. Mandia, “Determining the Climate Record,” Suffolk County Community College.

Possible Causes

Disease Depopulation and Mass Forest Regrowth

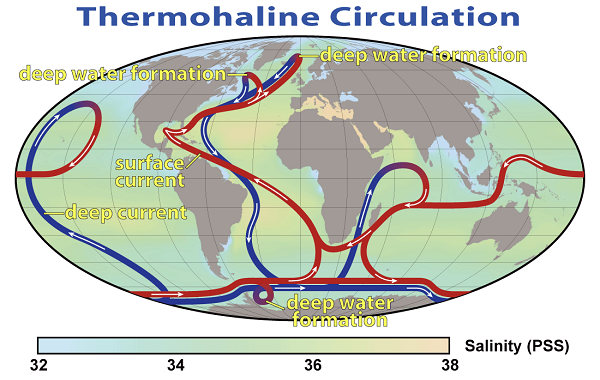

A possible related theory is that the increase in CO2 from the medieval period may have already wreaked havoc by dumping fresh water into the oceans and slowing the ocean conveyor belt, aka thermohaline circulation (or ocean density), which would have only exacerbated the problem. Although we tend to think of separate Atlantic and Pacific worlds, it’s important to remember that there’s actually one global ocean system connecting everything.

Thermohaline Circulation Belt 2 by Robert Simmons, NASA. Minor modifications by Robert A. Rohde also released to the public domain – NASA Earth Observatory. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons

So what caused the LIA? One theory stems from the dramatic population declines caused by the Black Death, which killed up to 200 million in Eurasia, and the conquest and diseases initiated by European colonialism that killed as many as 90 million in the Americas initially and millions more over two centuries. Mass population loss reversed the agricultural gains of the medieval warming period, and forests regrew, absorbing more CO2. The decrease in CO2 in turn created cooling patterns that impacted ocean oscillation systems globally such as the North Atlantic and El Nino weather patterns.

Sunspots and Volcanoes

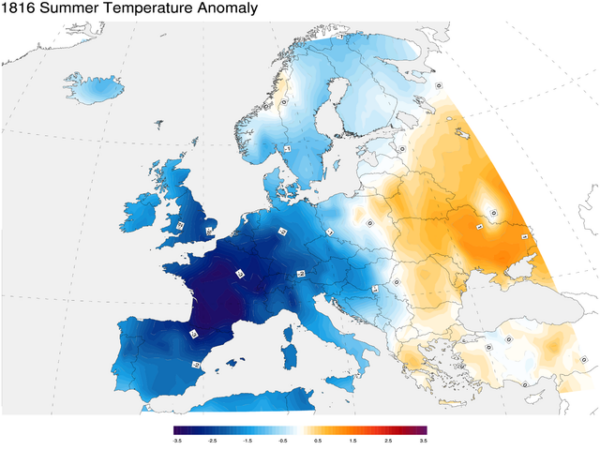

Still more causes of global climate change (now heavily debated) point to the dramatic decrease in sunspots during this era, reducing the sun’s radiation warmth, and a series of devastating volcanoes from the 14th to 19th centuries, which spewed sulfuric acid particles into the atmosphere, further reducing the sun’s radiation from reaching the earth.

1816 Summer by Giorgiogp2 – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons

Eruptions

- Series of 13th-century Indonesian eruptions

- 15th century: Indonesia

- 16th to 18th centuries: Indonesia, Philippines, Iceland

- 19th century: Indonesia

Recommended Readings

- William K. and Nicholas P. Klingaman, The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano That Darkened the World and Changed History.

- Sophie Yeo, “Scientists Dismiss Solar Link to Medieval ‘Little Ice Age,’” Climate Change News, December 23, 2013.

- “Study May Answer Long-Standing Questions about Little Ice Age,” Atmos News, January 30, 2012.

- Wynne Parry, “Volcanoes May Have Sparked Little Ice Age,” LiveScience, January 30, 2012.

- Renate Auchmann et al., “Extreme Climate, Not Extreme Weather: The Summer of 1816 in Geneva, Switzerland,” Climate of the Past 8 (February 24, 2012): 325–35.

Impacts of Climate Change around the World

Europe

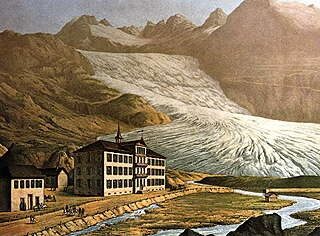

Rhonegletscher 1870 by Unknown. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons

The Little Ice Age was particularly devastating for Europe, producing longer winters and decreases in ocean fishing and agricultural productivity. An obvious sign of the cooling trend was the advance of glaciers across Germany and Switzerland. Less obvious impacts are seen in the frequent low-level famines and food shortages, which spread all kinds of social unrest, from bread riots, to peasant rebellions, to wars between kingdoms, and perhaps even early modern European witch hunts.

Recommended Reading: Brian Fagan, The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History, 1300–1850.

Collapse of Norse Network across the Atlantic (14th Century)

Up in the Arctic Circle, the dramatic cooling likely forced the Norsemen out of Greenland and prompted their settlement in North America. On the chart we can see clearly the way their network expanded during the warm period, completely collapsing by the first nadir point of the 14th century. This is especially significant if you consider that Norse withdrawal left the Americas completely isolated until the 16th century. So we can think of global climate change as yet another accidental factor in the Columbian exchange and conquest of the Americas.

Recommended Reading: John N. Harris, The Last Viking, last modified August 19, 2011.

17th-Century Crisis

Recommended Reading: Geoffrey Parker, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century.

The Little Ice Age and Impetus for Change in Europe

In the long term, climate crisis may have been one of the important factors providing Europe with the impetus for dramatic change. For example, agricultural declines led to mass land reclamation programs across Europe and eventually to the agricultural revolution. The reduction of fish schools, in addition to European disadvantages in trading with Asia, helped to prompt shipbuilding technologies leading to the rise of states able to maximize such benefits. A particular example of this phenomenon is the Dutch empire during the crisis era of the 17th century, whose extensive land reclamation programs fostered their meteoric rise. Along with the luck of coal deposits in England, these responses to specific crises are part of the larger explanation of why the Industrial Revolution occurred in Europe first.

Pacific World

Mega-droughts and Collapse of Civilizations

Polynesian Migration by David Eccles (Gringer (talk)) – Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Commons

Over in the Pacific world, the primary impact of global climate change was a series of so called “mega-droughts” believed to be behind the collapse of multiple civilizations from the Pueblo Empires of the American Southwest, the Khmer Empire of Angkor in Cambodia, and Great Zimbabwe on the East Coast of Africa, all three abandoned in the 14th century, to the collapse of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in China.

- Pueblo Empires, American SW (13th to 14th centuries)

- Khmer Empire (14th century)

- Mongol Empire in China (14th century)

- Great Zimbabwe (14th century)

Decline of Polynesian Voyages (15th Century)

At the farthest end of the Pacific, El Nino events likely caused the end of Polynesian voyages and the collapse of their connectivity across Oceania, again another factor in the isolation of the Americas. In addition, some scientists now point to long-term climate change as a possible explanation for the collapse of the Rapa Nui society on Easter Island.

Recommended Reading

- Ben Finney, “The Impact of Late Holocene Climate Change on Polynesia.”

- D’Aubert, AnaMaria and Patrick D. Numa. Furious Winds and Parched Islands

Atlantic World

Collapse of Roanoke and Jamestown (17th Century)

The study of tree rings, or dendrochronology, shows that a mega-drought of around the same time, was also a factor in the failures of the earliest New England colonies of Roanoke (the Lost Colony) and Jamestown, whose colonists had really bad timing, showing up during the worst drought in millennia.

Recommended Readings

- Extreme Droughts Played Major Role In Tragedies At Jamestown, “Lost Colony”

- David W. Stahle et al., “The Lost Colony and Jamestown Droughts,” Science 280 (April 24, 1998), 564–67.

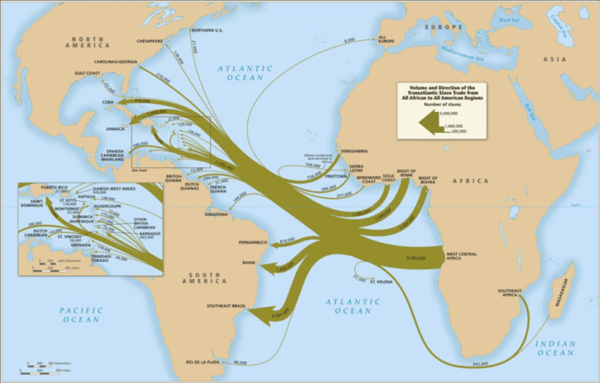

Map of volume and direction of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Courtesy David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, New Haven: Yale University Press 2010.

Sahel Mega-drought (1450–1700)

The same mega-drought pattern wreaked havoc for 250 years across the Sahel belt in Africa, the transitional zone between North Africa and the sub-Saharan. Likely, this long-term drought effectively separated powerful West African trade kingdoms, like Mali, from their traditional trade routes to the North, significantly increasing the impact of the trans-Atlantic slave trade by decreasing the demand for commodities such as gold, iron works, and salt.

This, along with continuous drought pulses along the coast of West Africa, coincided with a hugely increased market for human slaves when Europeans showed up at the coast within the first decades of the drought. Researchers have effectively demonstrated the role of drought and temperature in shaping the slave trade, showing that in years when temperatures were up merely 1 degree Celsius, creating more rain, slave sales decreased by 3,000 annually per active port.

Recommended Reading

- Levi Boxell, “A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade?” Stanford University, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, March 3, 2016.

- James Fenske and Namrata Kala, “Climate, Ecosystem Resilience and the Slave Trade,” July 2013.

- Geoffrey Parker, “Lessons from the Little Ice Age,” New York Times, March 22, 2014.

- Chris Arsenault, “Climate Change To Trigger Longer, Fiercer ‘Megadroughts,’ Study Warns,” Reuters, September 22, 2014.

- Ji-Hyung Cho, “The Little Ice Age and the Coming of the Anthropocene,” Asian Review of World Histories 2, no. 1 (2014): 1–16.

Map from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

Disease in Environmental History

Plantation Ecology and Mosquitoes

One of the most significant, but lesser known elements of the Atlantic biological exchange is the African mosquito. The new plantation ecology of the Caribbean and Americas involved rampant deforestation, which produced wetlands for sugarcane and rice. Slave plantations provided the perfect environments for mosquitos, which lived off of both cane juice and the millions of new human hosts.

Yellow Fever and Malaria in the Colonial Wars for the Americas

Just as Afro-Eurasian pathogens altered the balance of power in the Americas in the wake of early European conquest there, J. R McNeill, in his book Mosquito Empires, contends that two diseases emerged to dominate the demographic and military patterns shaping empire building across the Americas during the 17th through 19th centuries: malaria and yellow fever. While initially diseases aided the European invaders, by the late 17th century, an increasingly aggressive disease environment conferred, to use McNeill’s term, “differential immunity and resistance,” which proved to be enormous advantages for local inhabitants of the Americas during wars for colonial possessions and the series of anti-colonial revolutions that followed at the end of the century.

Recommended Readings

- J. R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914

- See also McNeill’s recent blog post for AHA Today, “Mosquitoes on the Move: Zika Virus and the Rise, Fall, and Rise of Aedes Aegypti in the Americas”

Cartagena de Indias by Luis Fernandez Gordillo

Battle of Cartagena de Indias, 1741

Notably, by the 18th century, the weakened Spanish Empire increasingly relied on environmental factors to enable them to hold on to their valuable territories in the Americas long after their decline as a top power. They resisted multiple attacks from European rivals primarily by fortifying key strongholds and recruiting local men, calculating that if they could hold out for one to two months in any given attack, they could count on yellow fever and malaria taking care of their adversaries. When the British attacked Spanish Columbia in 1741 in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias, the most significant battle of the weirdly named “War of Jenkin’s Ear” between the British and Spain, Admiral Vernon lost 22,000 of his 29,000 men to mosquito-borne diseases.

Mosquitoes and the Battle for Yorktown

Even more provocative is McNeill’s argument that mosquito-bred illnesses so utterly transformed the ecologies of the Americas that they paved the way for successful revolutions and the rise of independent nations: the United States, Haiti, and in South America. For example, at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, General Washington calculated the likelihood of British decimation by mosquitos as they had been entrenched in the Tidewater zone since June. The arrival of Washington’s mostly immune troops in September, the end of mosquito season, nearly guaranteed the probability of American success.

Disease in the Pacific

Captain Cook, who sailed during the American Revolution, was an unintentional vector for another kind of disease that would re-shape the societies it came into contact with: syphilis. The devastating spread of this disease into the Hawaiian islands can be traced to a single sailor on Cook’s ship, who was soundly whipped for breaking Cook’s prohibition that infected sailors were forbidden from sleeping with Hawaiian women. From that single encounter, the population of native Hawaiians was inalterably decimated, and along with other European diseases, reducing the Hawaiian people to less than one-tenth of their original population in less than a century.

Recommended Reading

- Seth. Archer, “Remedial Agents: Missionary Physicians and the Depopulation of Hawai’i,” Pacific Historical Review 79, no. 4 (November 2010).

- Seth Archer, “Sharks Upon the Land: Epidemics and Culture in Hawai’i, 1778–1865” (PhD diss., University of California, Riverside, 2015).

Guano and American Industrialization and Agriculture

19th-century ad for “Soluble Pacific Guano.” Courtesy Mystic Seaport

The guano trade from Latin America facilitated a worldwide revolution in agriculture and the production of nitrates for gunpowder, but relied heavily on forced labor. The Guano Islands Act, passed in 1856, allowed US citizens to claim any uninhabited island where guano, or bird excrement, was discovered. Americans claimed over 100 islands and commenced guano mining operations.

Recommended Reading

- Edward Melillo, “The First Green Revolution: Debt Peonage and the Making of the Nitrogen Fertilizer Trade, 1840-1930,” American Historical Review 117, no. 4 (2012): 1028–60.

- Cara Giaimo, “When the Western World Ran on Guano,” Atlas Obscura, October 14, 2015.

- Kevin Underhill, “The Guano Islands Act,” Washington Post, July 8, 2014.

- Monica Medina, “Thank Goodness for Guano,” National Geographic September 9, 2014.

- Gregory T. Cushman, Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History.

- “The Guano Trade,” The Norie Marine Atlas and the Guano Trade, Albert H. Small Documents Gallery Special Online Exhibit, National Museum of American History.

- Paul Goodwin, “Soluble Pacific Guano Poster: A Bird’s-Eye View of the Guano Trade,” Mystic Seaport for Educators.

Additional Sources on Environmental History

Recommended Textbook for World History with Environmental Emphasis

- Robert B. Marks, The Origins of the Modern World: A Global and Environmental Narrative from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-First Century

Online Resource

Other Recent Scholarship

- William Deverell and Greg Hise, Land of Sunshine: An Environmental History of Metropolitan Los Angeles.

- Christopher Manganiello, Environmental History and the American South: A Reader.

- William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England.

- J.R. McNeill, Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World.

- Ted Steinberg, Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History.

- James Beattle, Edward Melillo, and Emily O’Gorman, eds., Eco-Cultural Networks and the British Empire: New Views on Environmental History.