This resource was developed as part of the AHA’s Teaching Things project.

Materials

- Piece of tree bark or wood

- Swatch of fabric

- Stereoscope (May be available through libraries. Can also be purchased at antique stores. Reproductions are also available. If you are unable to acquire a stereoviewer, videos of their use may be available online.)

- Stereoviews (The stereoviews in this lesson plan can be printed to size and glued to cardboard. Some stereoviews have an image on the front and text on the back. Both should be provided to students.)

- Optional: Print issue of Harper’s Weekly (Reproduction issues are available online. Many libraries have issues of the newspaper in their collections.)

- Optional: Blocks of wood and carving tools

Assigned Reading

Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2008), chap. 1.

Learning Objectives

By the end of the session, students will:

- Be able to analyze different types of historical sources and identify their various perspectives and purposes

- Be able to explain how physical aspects of woodcut engraving and photographic processes affected the appearance of newspaper illustrations and photographs

- Develop skills in working with material objects as sources and subjects of historical research

- Be able to explain the ways in which Northern civilians learned about the Battle of Antietam and develop hypotheses about how this information affected their attitudes toward war

- Be able to articulate how the historical methods used in the lesson help historians write nuanced accounts of a particular event

The following materials include images and descriptions of battlefield death. Instructors should determine the appropriateness of this material for their students. The Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division has a large holding of stereoviews that can be printed to size.

Introduction

The Battle of Antietam, fought in Maryland in September 1862, was the single deadliest day of the American Civil War, with more than twenty-two thousand casualties. In its aftermath, Northern civilians encountered the battle through a range of images, texts, and material culture. Relics of the battlefield, such as bits of men’s uniforms and pieces of tree bark, were taken by soldiers who sometimes stashed these items in their knapsacks, but also sent them home in envelopes and packages, accompanied by letters describing their involvement in or experience of the aftermath of battle. People read newspaper articles describing and commenting on the battle. They encountered images of both the landscape and death through sketches, engravings, stereoviews, and, in New York City, a photographic exhibition.

Students can be divided into groups of three to four for this activity. As students work through the following sources, they should consider each item individually and then think about them in the context of one another, asking what these sources tell us about this particular historical moment.

Tools and Techniques

The Material Culture of Print Technology

In this section, students are introduced to the material culture of 1860s print technology, including photography, newspaper production, sketch artistry, and the preparation of illustrations from photographs for newspaper publication. If appropriate, instructors may use pieces of wood and small carving tools to allow students to try carving an image. Doing so helps students to understand the limitations of illustration technology and its effects on the images encountered by the public. For classes that are not exploring battlefield death, this section can also be taught separately.

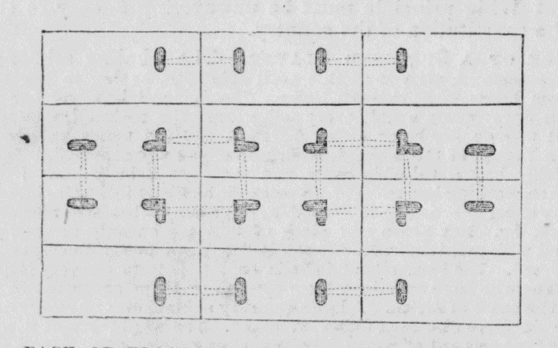

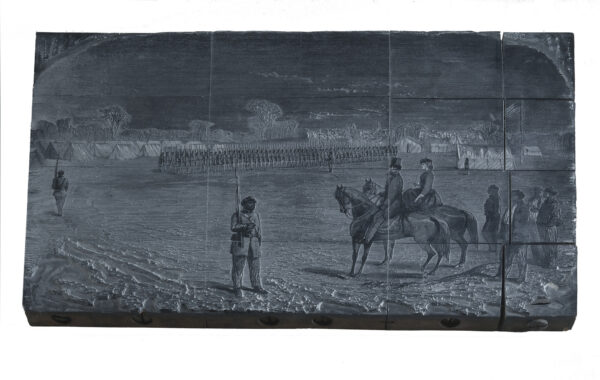

During the Civil War, images printed in newspapers were produced using woodblocks like the one depicted here. Once an image was selected for engraving, an artist traced and/or reworked the original image on a sheet of paper. This outlined drawing was then rubbed onto a polished and lightly whitewashed plank of Turkish boxwood so that the transferred lines could be easily seen.1 If the engraving was for a large image, such as the centerfold of a newspaper, the plank would be composed of multiple blocks of wood.

Figure 4. Back of a block, showing how it is fastened together.

Figure 5. Printing Block from a sketch by Arthur Lumley, “Camp of the 1st District Volunteers (Colored) on Mason’sIsland, Opposite Georgetown, D.C.”

After the image was transferred, several engravers worked on the individual block sections, which were screwed together before being finished by an engraver who smoothed out the image where the blocks were joined. Students should be asked to identify the outlines of individual blocks used to produce the image, as well as the location of the screws holding the blocks together (along the bottom edge). Have them reflect on what it would have been like to create this woodblock engraving.

Both sketch artists and photographers traveled with Civil War armies, often documenting camp life and the aftermath of battles. Newspaper engravings were often based on photographs, textual descriptions, or the work of sketch artists, the latter of whom may or may not have witnessed the events they depicted. Photographs themselves were not reprinted in newspapers until the 1880s. The images people encountered in newspapers, then, were shaped by the limitations of the material culture of print technology. The physical properties of wood and metal engraving tools could not achieve the same level of detail as could be captured in photographs.

Consider the Harper’s Weekly newspaper as a text, image, and object—something that a person physically holds in their hands and pages through.

- How is this experience different from and the same as the ways in which you typically consume media?

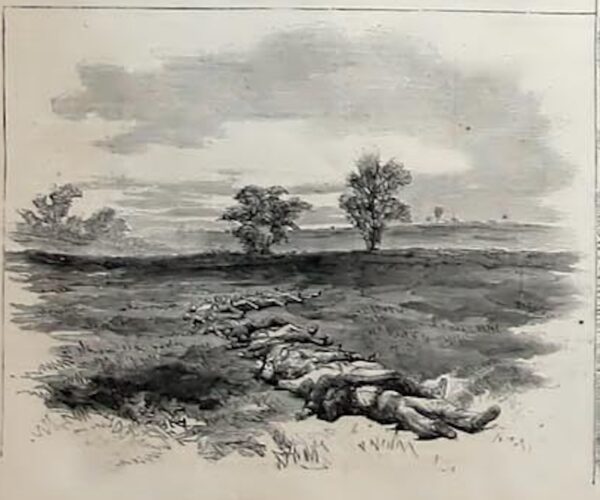

Examine the Harper’s Weekly image of soldiers awaiting burial after the Battle of Antietam and then read the accompanying October 18, 1862, article entitled “The Battle of Antietam.” After practicing close looking and reading, answer the follow questions:

- How do the descriptions of the illustrations in the newspaper differ from your own viewing of those illustrations?

- What reaction might readers have had to these scenes?

Figure 6. Harper’s Weekly image of soldiers awaiting burial after the Battle of Antietam.

Excerpt from “The Battle of Antietam,” Harper’s Weekly, Oct. 18, 1862.

We reproduce on pages 664 and 665 a number of photographs of the Battle of Antietam, taken by the well-known and enterprising photographer, Mr. M. B. Brady, of this city. The following description of these wonderfully lifelike pictures is from one who knew the ground:

The first of these pictures—the large view of Antietam creek and bridge, the crossing of which General Burnside effected at such a fearful sacrifice of life—exhibits little or no traces of the conflict. The spot is just as lovely and tranquil as when last we visited it. Artistically speaking, the picture is one of the most beautiful and perfect photograph landscapes that we have seen. The tone is clear and firm, but soft, and every object is brought out with remarkable distinctness.

Next to it is a smaller photograph, some seven inches square, which tells a tale of desperate contention. Traversing it is seen a high rail fence, in the fore-ground of which are a number of dead bodies grouped in every imaginal position, the stiffened limbs preserving the same attitude as that maintained by the sufferers in their last agonies. Minute as are the features of the dead, and unrecognizable by the naked eye, you can, by bringing a magnifying glass to bear on them, identify not merely their general outline, but actual expression. This, in many instances, is perfectly horrible, and shows through what tortures the poor victims must have passed before they were relived from their sufferings.

We now pass on to a scene of suffering of another character, where, under tents, improvised by blankets stretched on fencerails, we see the wounded receiving the attentions of the medical staff. Next to it is a bleak landscape on which the shadows of evening are rapidly falling, revealing, in its dim light, a singular spectacle. It is that of a row of dead bodies, stretching into the distance in the form of an obtuse angle, and so mathematically regular that it looks as if a whole reigment were swept down in the act of performing some military evolution. Here and there are beautiful stretches of pastoral scenery, disfigured by the evidences of strife, either in the form of broken caissons, dead horses, or piles of human corpses. In one place a farm-house offers visible marks of the hot fire of which it was the centre, the walls being battered in and the lintels of the windows and doors broken.

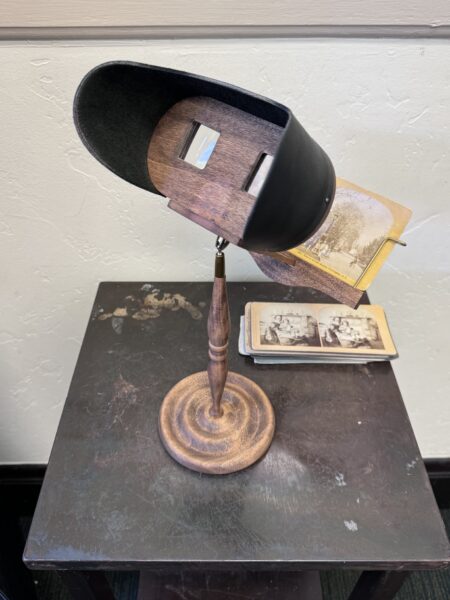

Figure 7. Stereoscope.

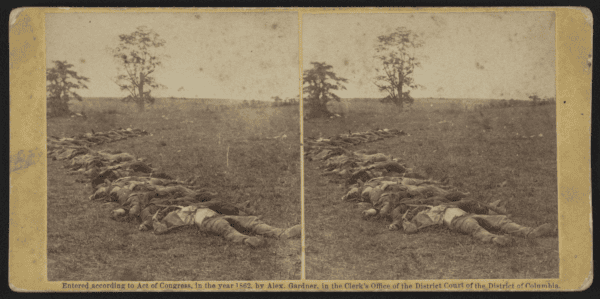

Figure 8. This stereoview is the same image as that published as the woodcut engraving in Harper’s Weekly.

Experiencing Stereoviews

Before there was VR, there was the View-Master. And before that: the stereoscope. Popularized in the 1850s, stereoviews and the typically handheld device by which to view them were a popular parlor pastime. Taken with a special camera with two lenses, two nearly identical images printed on a stereoview card merged into a three-dimensional picture when viewed through a stereoscope. The subject matter ranged from comical scenes to historic sites to Civil War battlefields. One might view the images by oneself, but more frequently, the stereoscope was passed from person to person, and the image became an object of conversation.2 Viewing stereoviews was—and is—an embodied experience that involved handling a physical object and adjusting the stereoview’s distance from the stereoscope’s lenses to achieve a three-dimensional effect. The images themselves allowed viewers to “travel” to new and distant places from their seats around a parlor table.

Have students handle the stereoscope, view the image through its lenses, and discuss the following questions:

- Consider the physical experience of holding and using a stereoscope. Is it heavy? How do you need to adjust your body to make viewing the image easier? Is it difficult to make the image pop into 3-D?

- What appeal would stereoviews have held for Americans in the mid-nineteenth century? How does the experience of looking at the stereoviews through the stereoscope compare to that of looking at the stereoviews with the naked eye?

- What is conveyed differently and the same in the newspaper illustration and the stereoviews? What might explain these differences (e.g., production techniques, social/cultural reasons, or the role of newspapers)?

- How might the experience of viewing battlefield death through these different formats have shaped the ways in which the viewers thought about the battle, the war, or death?

Photographs in the Built Environment

The Civil War was the first prolonged conflict in the United States to be extensively photographed. Dozens of photographers—some working for the government, others as private citizens—traveled with the US and Confederate armies. These photographers employed a wet collodion process that required five to twenty seconds of exposure.3 As a result, clear action shots could not be captured by this technology. Instead, many photographers walked the battlefield in its wake, documenting its death, destruction, and landscapes.

Three weeks after the Battle of Antietam, as the wounded recovered in hospitals and civilians anxiously searched for family members’ names on casualty lists, Mathew Brady’s Photographic Gallery in New York City opened an exhibition of “The Dead at Antietam.” In this gallery, visitors could view and purchase wartime photography.4

Have students consider the woodcut engraving of Mathew Brady’s Photographic Gallery. Although this particular image does not depict the Antietam exhibition, it provides evidence of the physical space of the gallery.

- Observe the material objects in the gallery as well as its layout and visitors. What does the image tell us about how a person would have viewed those photographs?

- How might viewing photographs in the gallery differ from viewing them at home? How did the physical and social experiences differ?

Figure 9. M. B. Brady’s New Photographic Gallery.

Excerpt from “Brady’s Photographs: Pictures of the Dead at Antietam,” New York Times, October 20, 1862.

The living that throng Broadway care little perhaps for the Dead at Antietam, but we fancy they would jostle less carelessly down the great thoroughfare, saunter less at their ease, were a few dripping bodies, fresh from the field, laid along the pavement.

. . .

Mr. BRADY has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it. At the door of his gallery hangs a little placard, “The Dead of Antietam.” Crowds of people are constantly going up the stairs; follow them, and you find them bending over photographic views of that fearful battle-field, taken immediately after the action. Of all objects of horror one would think the battle-field should stand preeminent, that it should bear away the palm of repulsiveness. But, on the contrary, there is a terrible fascination about it that draws one near these pictures, and makes him loth to leave them. You will see hushed, reverend groups standing around these weird copies of carnage, bending down to look in the pale faces of the dead, chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes. It seems somewhat singular that the same sun that looked down on the faces of the slain, blistering them, blotting out from the bodies all semblance to humanity, and hastening corruption, should have thus caught their features upon canvas, and given them perpetuity for ever. But so it is.

- Next, have students read the excerpt from the October 20, 1862, New York Times article entitled “Brady’s Photographs: Pictures of the Dead at Antietam.”

- How would encountering photographs like the “Bodies of Confederate Dead Gathered for Burial” at Brady’s Gallery have differed from viewing them as stereoviews at home or in newspapers?

- What might it have been like to view these photographs in the presence of other people, many of whom may have been strangers?

- Based on the newspaper account and images, how do you think viewing these images would have affected Northern civilians’ understanding of war? Would it have ignited people’s support for the war?

Objects from the Battlefield

Many civilians—Northerners and Southerners—received their news of the war from family members and friends who were fighting in the armies. In those letters, as well as packages, were mementos from the battlefield too. The vast number of material objects littering the field after a battle could be staggering: clothing, hats, boots, knapsacks, caissons, rifles, letters, buttons, exploded shells, splintered wagons. The pockets and gear of the dead and wounded, too, were filled with objects: letters, pocket Bibles, clothing, photographs, pencils, stamps, pipes.

In the immediate aftermath of a battle, both civilians and soldiers tramped through the field, picking up objects that littered the field. The items they took for themselves or to send to friends and family at home ranged from torn flags, bullets, and artillery shells, to canteens, cartes de visite, and pocket diaries. They also chopped up trees to obtain pocket-size pieces of wood in which bullets were embedded, and took pieces of bridges, like Burnside’s Bridge at Antietam, and other structures. Such relic hunting continued throughout the war and beyond. Indeed, museum collections are filled with items collected immediately after the battle and by relic hunters in the early twentieth century. Yet soldiers also rifled through the pockets of the dead and dying, some looking for objects of value, others for better clothing with which to supply themselves. At Antietam, a small mahogany inkstand was taken from the pocket of a soldier whose body was disinterred shortly after the battle.5 A rectangular piece of wood nearly eight inches long and two inches wide with a bullet embedded in it was cut from the Dunkard Church Woods on the Antietam battlefield and its edges smoothed.[6]

Surgeon William Child sent from Antietam to his wife in New Hampshire a letter in which he also enclosed “a bit of gold lace such as the rebel officers have.” This uniform trimming was not found lying on the battlefield. Rather, Child explains that “I cut [it] from a rebel officers coat on the battlefield.” He does not specify whether the coat was still on the body of a dead officer, but such an act would not have been uncommon.

Fig. 10: Tree bark. Photo by author.

William Child, Major and Surgeon with the 5th Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers

September 22, 1862 (Battlefield Hospital near Sharpsburg)

My Dear Wife;

Day before yesterday I dressed the wounds of 64 different men – some having two or three each. Yesterday I was at work from daylight till dark – today I am completely exhausted – but stall soon be able to go at it again.

The days after the battle are a thousand times worse than the day of the battle – and the physical pain is not the greatest pain suffered. How awful it is – you have not can have until you see it any idea of affairs after a battle. The dead appear sickening but they suffer no pain. But the poor wounded mutilated soldiers that yet have life and sensation make a most horrid picture. I pray God may stop such infernal work – through perhaps he has sent it upon us for our sins. Great indeed must have been our sins if such is our punishment.

Our Reg. Started this morning for Harpers Ferry – 14 miles. I am detailed with others to remain here until the wounded are removed – then join the Reg. With my nurses. I expect there will be another great fight at Harpers Ferry.

. . .

In this letter I send you a bit of gold lace such as the rebel officers have. This I cut from a rebel officers coat on the battlefield. He was a Lieut.

There was an important distinction between the act of picking up items from the ground and searching dead and dying men’s pockets. Items picked up from the battlefield after bodies had been removed and buried were items that were divorced from the men themselves; to take something directly from a dead body, on the other hand, was far a far more physical experience and violating.6

Ask students to read William Child’s September 22, 1862, letter written to his wife from the battlefield hospital near Sharpsburg, Maryland.

- How does Child’s firsthand account of the battle differ from the description in the Harper’s Weekly article?

- What emotions might handling a piece of a Confederate officer’s uniform trimmings have evoked for Mrs. Child, whose husband was a US officer?

Have students handle a modern swatch of fabric or a piece of tree bark. Imagine the experience of opening up a package to find something that the letter writer had taken from the battlefield.

- How might this feel for the person at home?

- Would it have made the battle seem more real?

- Would it have helped them feel more connected to the letter writer? Why or why not?

When students have completed the close looking and analysis exercises, the following questions can be used to guide a full-class discussion about the broader implications of the sources with which they have engaged:

- How did Americans’ encounters with the war differ depending on their proximity to the battlefield?

- How was the experience of viewing a photograph versus a newspaper illustration different and the same?

- In what ways do personal letters about the battle differ from newspaper accounts? What information was lost or added? Why?

- Who claimed to have the authority to relate the experience of war, and on what basis?

- How might these objects, images, and texts have shaped people’s attitudes toward war? Where could we look for more information to test our hypotheses?

At the conclusion of the lesson, students should have developed an understanding of the Civil War as an event experienced in the material, physical world by not only soldiers but also civilians. Holding a stereoscope to look at three-dimensional stereoviews, handling relics from the battlefield, and encountering graphic images of death and dying had emotional effects on people and influenced how they read newspaper accounts and letters from the battlefront. Students should also reflect on what they learned about historical methods while participating in these activities. They should be able to articulate that using multiple kinds of sources helps historians develop a nuanced and layered account of the Battle of Antietam.

Additional Reading

Barnett, Teresa. Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Brown, Joshua. Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2008.

Gardner, Alexander. Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the Civil War. New York: Dover, 1959.

Weicksel, Sarah Jones. “‘Peeled’ Bodies, Pillaged Homes: Looting and Material Culture in the American Civil War Era.” In Objects of War: The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement, edited by Leora Auslander and Tara Zahra, 111–38. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Notes

- For further detail about this process, see Joshua Brown, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 34–39. [↩]

- For more on the social and cultural aspects of stereoscopes, see Shirley Wajda, “A Room with a Viewer: The Parlor Stereoscope, Comic Stereographs, and the Psychic Role of Play in Late Victorian America,” in Hard at Play: Leisure in America, 1840–1940, ed. Kathryn Grover (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992), 112–38. [↩]

- Students can view a video about the wet collodion process created by the Getty Museum. [↩]

- Jeff L. Rosenheim, Photography and the American Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 7–15. [↩]

- Soldier’s pocket inkstand from Sharpsburg (Antietam), 1862, Virginia Museum of History and Culture, object no. 1990.100.407. [↩]

- Sarah Jones Weicksel, “‘Peeled’ Bodies, Pillaged Homes: Looting and Material Culture in the American Civil War Era,” in Objects of War: The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement, ed. Leora Auslander and Tara Zahra (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 111–38, here 117–18. [↩]