This resource is part of the Silk Roads and Beyond: Trade, Exchange, and Travel in Ancient and Medieval Afro-Eurasia toolkit, from the AHA’s Teaching Things project.

Materials

- Modern US coins (preferably quarters, due to their size and visibility) for each student to examine

- Magnifying glasses

Introduction

Numismatics—or the study of coins, currency, and medals—is an integral part of understanding economics and trade in the past. In this lesson, students will consider how these material objects, often buried and only discovered centuries or millennia later, provide important historical evidence. The distribution, appearance, and materiality of coins can demonstrate the geographic extent of trade as well as distinct cultural aspects of different kingdoms and empires.

Part I: How Coins Are Made

Watch: Art Institute of Chicago, Coin Production in the Roman World (2:35 mins)

For elementary students, watch: US Mint, How Coins Are Made . . . For Kids (3:12 mins)

For middle school, high school, and college, watch: US Quarter Minting Process (4:28 mins)

Discussion questions

- What are the similarities and differences between ancient and modern coin production?

- What in these videos did you find unexpected or surprising?

Part II: The Lifecycle of Coins

(Elementary only): Explore the “Life of a Coin” page on the US Mint for Kids website.

(Middle school, high school, and college): Consider coins in a moment of transition by watching two brief news clips, from Canada and New Zealand respectively, about the effect on currency of Queen Elizabeth II’s death.

CTV News, “Here’s why Queen Elizabeth II will grace UK coins for at least thirty more years” (1:58 mins)

Newshub, “What will happen to our money, passports? Here’s what Queen Elizabeth II’s death means for NZ” (2:09 mins)

(Middle school, high school, and college): Have a class discussion about the life cycle of coins (in the past and the present) by prompting students with the following questions:

- What does it mean for a coin to be “in circulation”?

- How far might a coin travel while it is in use? In other words, would an ancient Roman coin only remain in the Italian peninsula? Are American coins only in the United States?

- Though coins might be taken out of circulation and melted down for other purposes, many coins survive decades, centuries, or even millennia. How do you imagine these coins survived for so long? In what contexts do you think archeologists and historians have found historical coins?

- On a map of Afro-Eurasia, where might you expect to find coins from regions that participated in trade along the Silk Roads?

- Why in those places? (Use UNESCO’s Interactive Silk Road Map as a resource.)

Afro-Eurasia. Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

Discussion takeaways for educators

Students should be able to:

- Articulate the differences between a coin that is actively manufactured and in circulation versus no longer manufactured and/or pulled from circulation.

- Explain the broad geographical reach of coins in the premodern period and today due to trade and travel.

- Identify multiple examples of where historical coins might be found (including, but not limited to: marketplaces and trading centers, trash heaps and latrines, burial sites, domestic spaces, religious sites)

Part III: The Meaning of Coins

In small groups, examine modern US coins (front and back).

- Each group should practice close-looking:

- What do you see?

- What does this coin communicate about American culture? How do you know?

As a larger group, make a list of all findings together.

Activity takeaways for educators

(Elementary only) Students should be able to identify:

- Image of person

- Things

- Words

- Numbers

(Middle school, high school, and college) Students should be able to identify:

- Important people/leaders (e.g., George Washington)

- Cultural values (e.g., religion)

- Meaningful symbols (e.g., eagle)

- Mint year and location

Additional note: “In God We Trust” became the official US motto in 1956. It replaced “E pluribus unum” (Latin for “Out of many, one”), which had been the de-facto motto since the 18th century. “In God We Trust” also has a lengthy history. The phrase first appeared on coins during the Civil War period. Both famous aspects of American coins communicate important and distinct aspects of American culture and should be emphasized to students.

Part IV: Silk Roads Case Study, Aksumite Coins

The Kingdom of Aksum (or Axum)—in the region of eastern Africa that is now Ethiopia—played an important role in the Indian Ocean trade that was part of the broader Silk Roads network.

Begin by having students watch the PBS video, “The Aksum Kingdom: Trade and Ancient Africa | Africa’s Great Civilizations,” (8:06 mins)

Discussion questions

- What items did Aksum trade with other communities along the Silk Roads, particularly those in the Indian Ocean networks?

- What was the function of the large, monumental stelae? How were they constructed?

Classroom Activity: Examining Aksumite Coins

For each coin, prompt students to remember the different aspects of modern American coins and determine what similarities can be found in these ancient African objects. By exploring these objects chronologically, students should be able to notice the emergence of the use of the cross on Aksumite coins instead of the crescent and disc. This is a visual indication of the shift from polytheism to Christianity in Aksum.

The crescent and disc are common symbols in South Arabian polytheism, which was transmitted to Aksum across the Red Sea. It’s important to emphasize to students that while this early symbol influenced the later use of the crescent moon in Islam, they are distinct symbols. The crescent disc predates Islam’s foundations in the seventh century.

Students should also notice visual depictions objects associated with royal status, including headdresses, crowns, scepters, and wheat stalks (which are thought to symbolize the ability of the king to feed and care for his people).

Guided visual analysis questions

- How are the rulers depicted? How did these depictions change across time?

- How might the meaning of an image of a ruler change during their lifetime versus after their death?

- What objects are the rulers holding? What objects surround them?

- Are there symbols that are recognizable to you? What might they indicate?

- Why might the Kingdom of Aksum, already heavily involved in international trade by the fourth and fifth centuries, decide to put a religious symbol on their coins? What benefit would there have been to do so?

One of two coins depicting King Ousanas (the first Christian King of Aksum) and an anonymous king, fourth century, Aksum, Gift of Joseph and Margaret Knopfelmacher, 1996, 59.794. Walters Art Museum.

Coin depicting King Ebana, depicted with crown, scepter, and wheat stalks (left) and wearing headcloth, scepter, and wheat stalks (right), c. 450–500, Aksum, 1904,0404.1. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Coin depicting King Ioel on one side (left) and cross on the other (right), c. 550–600 CE, Aksum, 1989,0518.363. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Religion on Coins

Coins from Aksum provide material evidence that religion and other cultural aspects, not just commodities, traveled the Silk Roads. The precise mechanisms behind the establishment of Aksum as a Christian kingdom, however, have been contested by historians. While some assert that it was part of an almost accidental missionizing endeavor that resulted in top-down conversion, others argue that trade facilitated a kind of bottom-up conversion beginning with merchants.

To further explore these debates, have students read Eivind Heldaas Seland, “Early Christianity in East Africa and Red Sea/Indian Ocean Commerce,” African Archaeological Review 31 (2014): 637–47. (The primary source referenced in this article can be found in Rufinus of Aquileia, The Church History of Rufinus of Aquileia: Books 10 and 11, trans. Philp R. Amidon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 19–20.

Discussion questions

- What is the traditional historical narrative of the conversion of Aksum to Christianity?

- What does Seland argue is the more likely reality of conversion?

- What is the relationship between trade and religion along the Silk Roads, according to Seland? What evidence does the author provide?

Part V: Afterlives of Coins

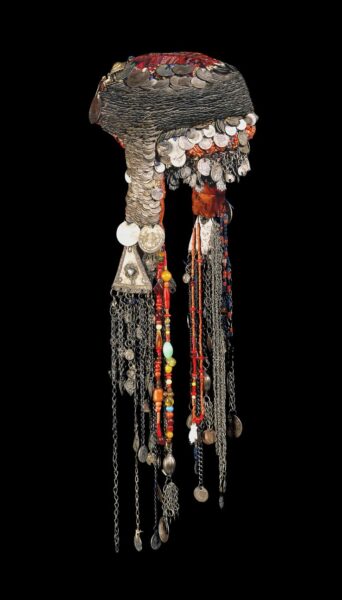

There are numerous examples of the decorative use of coins throughout history. Encourage students to consider how historical coins have functioned outside of their original circulation use. Have students examine these objects closely and consider the following questions:

- Why might artisans choose coins to adorn objects such as these? And why might people wear them?

- What is a coin’s worth and significance if it is not being used as currency? Is it purely symbolic?

- Can you think of any examples of ways that coins are used for nonmonetary purposes today?

Gold necklace with coin pendants, third century CE, Roman. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917. 17.190.1655. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art website: “Two openwork pendants are suspended from a double chain of figure-of-eight loops. Each pendant is set with an aureus (gold coin) of the Emperor Alexander Severus (r. A.D. 222–235). Their different sizes and the second spacer suggest that additional pendants are now missing from the chain. The use of coins in jewelry became very fashionable in the third century and persisted until the early seventh century.”

Head-dress, 19th century, Palestine. Cotton, coral, and silver. As1986,04.5. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

From the British Museum website: “During the 1800s and early 1900s, brides in the villages of the Hebron hills wore a ceremonial headdress called a ‘wuqayat al-darahim’ (‘money hat’). With its densely-packed rows of Ottoman coins and numerous beads, charms and pendants, the headdress shielded a bride from the ‘eye of envy’ when she was most vulnerable—on procession to her new home and at her second public appearance celebrating the consummation of the marriage known as the ‘going out to the well’ ceremony.”

Additional Teaching Resources=

The British Museum, “Aksumite Coins,” Smarthistory, September 23, 2016.

National Geographic, “The Kingdom of Aksum.” (Readings can be adjusted for grades 3–12)

Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. “Foundations of Aksumite Civilization and Its Christian Legacy (1st–8th Century).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2000)

Ross, Emma George. “African Christianity in Ethiopia.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2002)

Additional Readings

Dowler, Amelia. “The Interaction of Aksumite and Roman Gold Coins in South Arabia in the 6th Century CE,” JONS 233 (Autumn 2018): 5–28.

Feingold, Ellen R. The Value of Money. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2015.

Holt, Frank L. When Money Talks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Paulau, Stanislau and Martin Tamcke, eds. Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity in a Global Context: Entanglements and Disconnections. Texts and Studies in Eastern Christianity, Vol. 24. Leiden: Brill, 2022.