This resource is part of the Silk Roads and Beyond: Trade, Exchange, and Travel in Ancient and Medieval Afro-Eurasia toolkit, from the AHA’s Teaching Things project.

Optional Materials

- Swatch of silk or silk garment(s) to allow students to tactilely interact with woven silk material

- Silkworm cocoon (available for purchase online)

Introduction

Silk was a particularly sought-after commodity on the Silk Roads. China—during the Han Empire, Age of Division, Sui Dynasty, and Tang Dynasty (206 BCE to 907 CE)—was unquestionably the world’s primary supplier of silk. The production of silk, or sericulture, was first introduced in China in the third millennium BCE. While it may be an exaggeration to call China’s silk trade a monopoly, it is clear from historical sources that China was extremely protective of its silk trade secrets and Chinese silks were among the most expertly crafted on the market.

Yet many other regions of the world wanted to better understand the silk-making process and obtain the materials necessary to practice sericulture. Several stories of theft and smuggling exist from late antiquity and the early Middle Ages to explain the emergence of silk-making in regions outside China. While not rooted in historical reality, these legends of silk heists were nonetheless culturally meaningful.

In this lesson, students will explore the specifics of sericulture as well as two of the most famous silk heist legends: the smuggling of silk to Khotan and Justinian I’s Byzantium.

Part 1: Sericulture (CORE)

Watch: Vox, How silkworms make silk (1:42 mins)

Watch: American Museum of Natural History, Traditional Silk-Making (3:05 mins)

Discussion questions

- What materials would need to be stolen in order to successfully produce silk outside of China?

- Does the silk-making process itself offer clues that explain the luxurious nature of silk? In other words, why was (and is) silk an expensive luxury good?

Discussion takeaways for educators

Students should be able to:

- Name silk-making materials: silkworms (which are not, in fact, worms but larvae of the silk moth); silkworm cocoons; mulberry trees (and mulberry leaves, in particular, which are the food source for silkworms)

- Explain that the high value of silk and its luxury status is due to the very specific materials needed and the painstaking process of extracting raw silk from cocoons and then transforming it into woven textiles. Even in today’s modern world where silk-making is industrialized to some extent, real silk comes from animal materials that cannot be replicated. (Man-made fibers like rayon and synthetic silks exist, but they are not of the same quality.) The specificity of materials and special skill required to create the product, as well as its exceptional quality, makes it more scarce than other textiles on the market, and thus a luxury material.

Part 2: The Silk Princess of Khotan

Listen to episode 50: “Silk Princess Painting,” from A History of the World in 100 Objects, produced by the British Museum and BBC (transcript available on the BBC’s website).

- Note: The podcast website offers helpful images and supplementary information. However, the podcast is best listened to on another platform, such as Spotify.

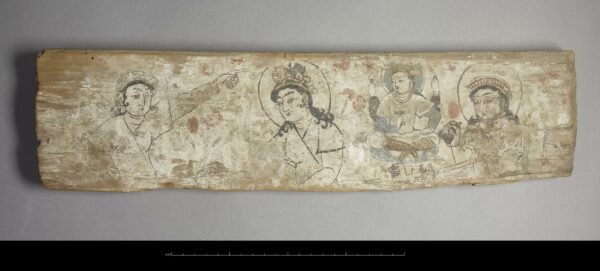

Votive panel, 木板畫, also known as the “Silk Princess Painting,” c. 6th-8th centuries, Khotan, 1907,1111.73. © The Trustees of the British Museum/ CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Discussion questions

- What is the legend of the Silk Princess? How did she smuggle silkworms from China to the Khotan region (then, a separate kingdom)?

- What is the function of the panel object described in the podcast?

- Can you think of any modern objects that serve similar story-telling functions?

- How believable is this story, considering the realities of silk worm production? What other purposes could this story serve?

Note: The primary source text for this story is Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (Da tang xi yu ji), composed by a Chinese Buddhist monk, Xuánzàng (602–64), in 646 at Chang’an. In Chapter 12, Xuánzàng relates a story of silkworms being secretly imported from Tang China to Khotan around the fifth century. For more context, see Murata, Koji. “Procopius in the Far East: Japanese Language Studies and Translations.” Histos Supplement 9 (2019): 16.1–13.

Part 3: Justinian’s Monk Heist (CORE)

Read and consider these primary source texts that offer related, but competing, narratives of how Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–65 CE) brought sericulture to Byzantium:

Procopius, History of the Wars excerpt, c. mid-sixth century1

About the same time there came from India certain monks; and when they had satisfied Justinian Augustus that the Romans no longer should buy silk from the Persians, they promised the emperor in an interview that they would provide the materials for making silk so that never should the Romans seek business of this kind from their enemy the Persians, or from any other people whatsoever. They said that they were formerly in Serinda, which they call the region frequented by the people of the Indies, and there they learned perfectly the art of making silk. Moreover, to the emperor who plied them with many questions as to whether he might have the secret, the monks replied that certain worms were manufacturers of silk, nature itself forcing them to keep always at work; the worms could certainly not be brought here alive, but they could be grown easily and without difficulty; the eggs of single hatchings are innumerable; as soon as they are laid men cover them with dung and keep them warm for as long as it is necessary so that they produce insects. When they had announced these tidings, led on by liberal promises of the emperor to prove the fact, they returned to India. When they had brought the eggs to Byzantium, the method having been learned, as I have said, they changed them by metamorphosis into worms which feed on the leaves of mulberry. Thus began the art of making silk from that time on in the Roman Empire.

Theophanes Confessor, The Chronicle, c. early 9th century2

A certain Persian [he tells us] exhibited in Byzantium the mode in which (silk) worms are hatched, a thing which the Romans had never known before. This Persian on coming away from the country of the Seres had taken with him the eggs of these worms (concealed) in a walking-stick, and succeeded in bringing them safely to Byzantium. In the beginning of spring he put out the eggs upon the mulberry leaves which form their food; and the worms feeding upon those leaves developed into winged insects and performed their other operations. Afterwards, when the Emperor Justinian showed the Turks the manner in which the worms were hatched, and the silk which they produced, he astonished them greatly. For at that time the Turks were in possession of the marts and ports frequented by the Seres, which had been formerly in the possession of the Persians. For when Epthalanus King of the Ephthalites (from whom indeed the race derived that name) conquered Perozes and the Persians, these latter were deprived of those places, and the Ephthalites became possessed of them. But somewhat later the Turks again conquered the Ephthalites and took the places from them in turn.

Discussion questions

- What story does each of these sources tell about Justinian and the silkworms?

- Who were Justinian’s accomplices in each story?

- Is their role in theft surprising? Why or why not?

- What might these stories indicate about the relationship between the state and religion in Byzantium this period?

- Does each story account for the precise method of smuggling, travel, and the creation of sericulture in Byzantium?

- Consider what you have learned about silkworms and silk production. How believable is this story? What other purposes could this story serve?

Although Justinian’s heist allegedly occurred in the sixth century, it had lasting influence on visual culture, as evidenced in artworks completed more than a millennium later.

Guided Visual Analysis Questions

- Who are the central figures in the image? What objects/clothing/adornments indicate their identities?

- What is the function of this image as an object? In other words, is this art for art’s sake or something more?

Emperor Justinian Receiving the First Imported Silkworm Eggs from Nestorian Monks, Plate 2 from “The Introduction of the Silkworm” [Vermis Sericus] ca. 1595, Karl van Mallery, the Netherlands. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949, 49.95.869(3). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Translation of Latin inscription: Two monks of Emperor Justinian give him the eggs from the silkworm.

Additional Resources

Good, I. L., J. M. Kenoyer, and R. H. Meadow. “New Evidence for Early Silk in the Indus Civilization.” Archaeometry 51, no. 3 (2009): 457–66.

Munroe, Nazanin Hedayat, “Woven Silk.” June 25, 2012.

Wu, Gang. “Mapping Byzantine Sericulture in the Global Transfer of Technology.” Journal of Global History 19, no. 1 (March 2024): 1–17.

Notes

- Excerpt from Procopii Caesariensis Historiarum Temporis Sui Tetras Altera. De Bello Gothico, trans. Claudius Maltretus (Venice, 1729), Lib. IV, cap. XVII, p. 212; reprinted in Roy C. Cave and Herbert H. Coulson, eds., A Source Book for Medieval Economic History (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Co., 1936; reprint ed., New York: Biblo and Tannen, 1965), 244–45. Scanned by Jerome S. Arkenberg, California State University, Fullerton, who has modernized the text. [↩]

- Excerpt from Sir Henry Yule, “Cathay and the Way Thither Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China,” London, UK, 1866, as cited in Healanor B. Feltham, “Justinian and the International Silk Trade,” in Sino-Platonic Papers, n. 194 (November 2009), 17. [↩]