About the Briefing

This handout was created for the AHA’s June 11, 2025, Congressional Briefing offering historical perspectives on tariffs. Panelists Douglas A. Irwin (Dartmouth Coll.), Sharon Ann Murphy (Providence Coll.), and Eric Rauchway (Univ. of California, Davis) discussed how the government has implemented tariffs in the past, and how they have impacted the domestic and global economies.

The recording of the briefing is available to watch on C-SPAN.

Glossary

- Agriculture: the extraction and harvesting of natural resources

- Great Depression: a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939

- Import tariff (or import duties): a tax on foreign goods imported into the country

- Export tariff: a tax on domestic goods exported out of the country

- Logrolling: trading of political favors for votes

- Manufacturing: the processing of raw materials to produce goods such as textiles, steel, or machinery

- Most-favored nation clause: a provision that any trade advantage offered to another country be offered to the signatory nation, meant to prevent discriminatory trade

- Profit: gross income minus expenses

- Protective tariff: a tariff designed to restrict imports, with the goal of protecting domestic industries, rather than to generate revenue for the government

- Reciprocity: lowering tariffs in exchange for other countries agreeing to lower their tariffs

- Revenue: gross income before expenses

- Revenue tariff: a tariff designed to generate revenue for the government, rather than to restrict imports

- Services: retail and trade, finance, transportation, health care, education, information technology, etc.

- Trade agreements: a formal agreement between countries governing their trade relationships for importing and exporting goods and services. The agreements can include tariffs, nontariff barriers, and prohibitions.

- Trade policy: a government’s policy for international trade, including agreements, regulations, practices, and strategies

The Three “Rs”: Revenue, Restriction, and Reciprocity

- An import tariff is a tax on foreign goods imported into the United States. Under Article I, Section 8 of the US Constitution, Congress has the authority to levy taxes on imports, but export taxes are forbidden under Article I, Section 9.

- Starting with the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, some tariff powers have been delegated to the president.

- What objective is a government trying to achieve in levying taxes on imports? Three objectives stand out:

- To raise revenue for the federal government

- To restrict imports and protect domestic producers from foreign competition

- To achieve reciprocity through agreements that reduce trade barriers. These can be summarized with the three R’s: revenue, restriction, and reciprocity.

- At any point in time, all three objectives can be in play and subject to sharp political debate. Yet the history of US trade policy can be divided into three eras in which one of them is predominate.

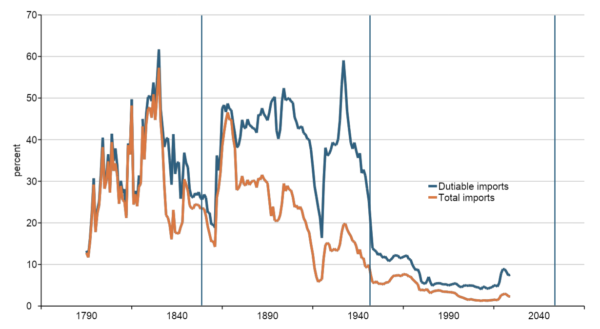

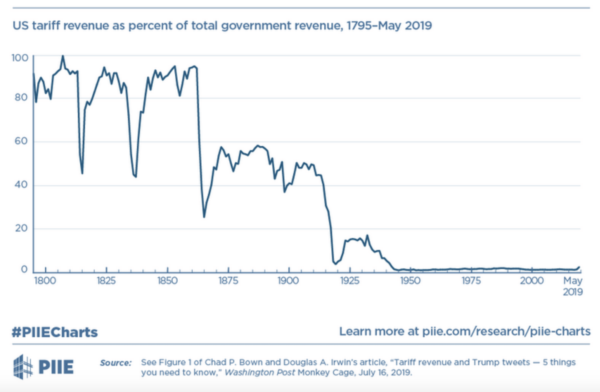

- From 1790 to 1860: revenue considerations were paramount in the setting of tariffs, because import duties raised about 90 percent of receipts of the federal government.

- From 1861 to 1933: government revenue came increasingly from domestic taxes, and therefore import duties were imposed mainly to protect domestic producers from foreign competition.

- From 1934 until 2016: the primary goal of trade policy has been to reach trade agreements with other countries.

- Trade agreements have been reached through various pathways:

- Multilaterally through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO)

- Regionally in agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, later USMCA) or the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA)

- Bilaterally in agreements with countries such as Israel, Singapore, Australia, Korea, and others

- Since 2016, higher tariffs have been imposed to protect the steel industry from foreign competition and reduce dependence on China.

Average US import tariff, 1790–2023

Origin and Purpose of Presidential Tariff Authority

- The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 was the last in a series of laws showing that congressional rate-setting tended to produce higher tariffs through logrolling: lawmakers secured support for higher rates on the goods produced in their own district by supporting higher rates on the goods produced in their colleagues’ districts.

- During the Great Depression, even farmers—who historically preferred lower tariffs to ensure a global market for their goods—sought protection. Smoot-Hawley’s high rates spurred other countries’ retaliation and reduced world trade.

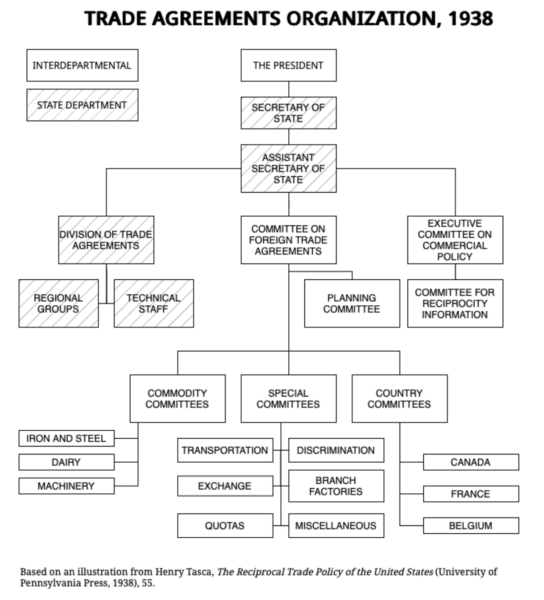

- Delegating reciprocal tariff-lowering power to the presidency changed the tariff from a logrolling mechanism to a regulatory policy carried out with expert consultation. Together with more internationalist monetary policy, this practice inaugurated a period of international economic cooperation and widespread support for freer trade on the recognition that it opened markets and increased prosperity.

- Franklin Roosevelt ran in 1932 on lowering the tariff to relieve the Depression, and voters who backed the New Deal expected it. Reciprocity—lowering tariffs in exchange for other countries doing likewise—would open markets, bringing down trade barriers that had worsened the Depression.

- Congress passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act in 1934. Before the Act, Congress periodically revised the tariff by statute, but with the Act it began delegating that power to the president.

- Lodging tariff powers with the president also allowed lawmakers to avoid responsibility for lower rates. This shift away from economic nationalism led to a more general internationalism that helped bring recovery from the Great Depression, victory in World War II, and subsequent decades of prosperity.

Agriculture, Manufacturing, and Services

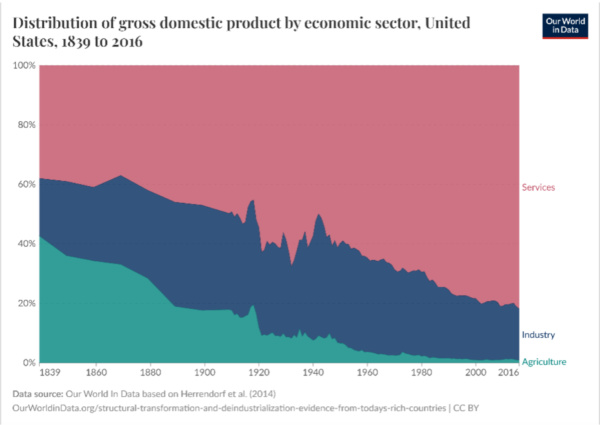

- As the US economy has matured over the course of its 250-year history, its composition has shifted significantly out of agriculture and into manufacturing and services.

- From the 1870s to the 1970s, manufacturing accounted for approximately 20-25% of employment and 30-40% of gross national product (GDP).

- Since the 1970s, the manufacturing sector has steadily declined as a proportion of the US economy, driven by a combination of automation, capital deepening, and globalization. This not only means the employment of fewer people in manufacturing, but also a shift in the types of people hired in manufacturing away from low-skilled workers towards more high-skilled workers.

- In contrast, the service sector of the economy has continued to grow steadily. Since the 1950s, this growth has been primarily driven by industries requiring high-skilled service jobs that place a premium on the acquisition of education.

- The United States has held a comparative advantage in these high-skilled service jobs, accounting for our dominance in research and development, technological innovation, and education services.

- Historically, the implementation of tariffs has had only a minimal effect on this transition. Nineteenth-century tariffs provided protection for certain industries but did not cause the transition to manufacturing. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff did not stop the transition out of agriculture. Trade agreements like NAFTA did not cause the decline in manufacturing, although it may have accelerated existing trends.

Participant Biographies

Douglas Irwin is John French Professor of Economics at Dartmouth College. He is the author of Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy, Free Trade Under Fire, Trade Policy Disaster: Lessons from the 1930s, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, among other books, and many articles on trade policy and economic history in books and professional journals. He is a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research and a non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He worked on trade policy issues while on the staff of President Ronald Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers and later worked in the International Finance Division at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington, DC.

Eric Rauchway is Distinguished Professor of History at the University of California, Davis. He is the author of seven books on US history, including four on the Great Depression and New Deal. His most recent books are Why the New Deal Matters and Winter War: Hoover, Roosevelt, and the First Clash Over the New Deal.

Sharon Ann Murphy is a professor of history at Providence College. She specializes in the financial history of the United States, with a particular interest in the complex interactions between financial institutions and their clientele. Her latest book, Banking on Slavery: Financing Southern Expansion in the Antebellum United States, examines the relationship between commercial banks and the development of the southern frontier during the first half of the nineteenth century. Her other books include Life: Insurance in Antebellum America and Other People’s Money: How Banking Worked in the Early American Republic.