About the Briefing

This handout was created for the AHA’s July 28, 2025, Congressional Briefing that places the issue of immigration along the southern US border in historical context. Geraldo Cadava (Northwestern Univ.), Nara Milanich (Barnard Coll., Columbia Univ.), and Mae Ngai (Columbia Univ.) presented historical perspectives on the southwestern border as the main site of controversy over immigration to the US.

The recording of the briefing is available to watch on C-SPAN.

Multiple Perspectives on Southwestern Borderlands: History,

Immigration, and Commerce

- History of Latino views of immigration, the border, and US-Latin American relations.

- The borderlands not only as a crossroads for migrants entering and leaving the United States, but as a home to millions of Americans and Mexicans who cross the border daily as a way of life.

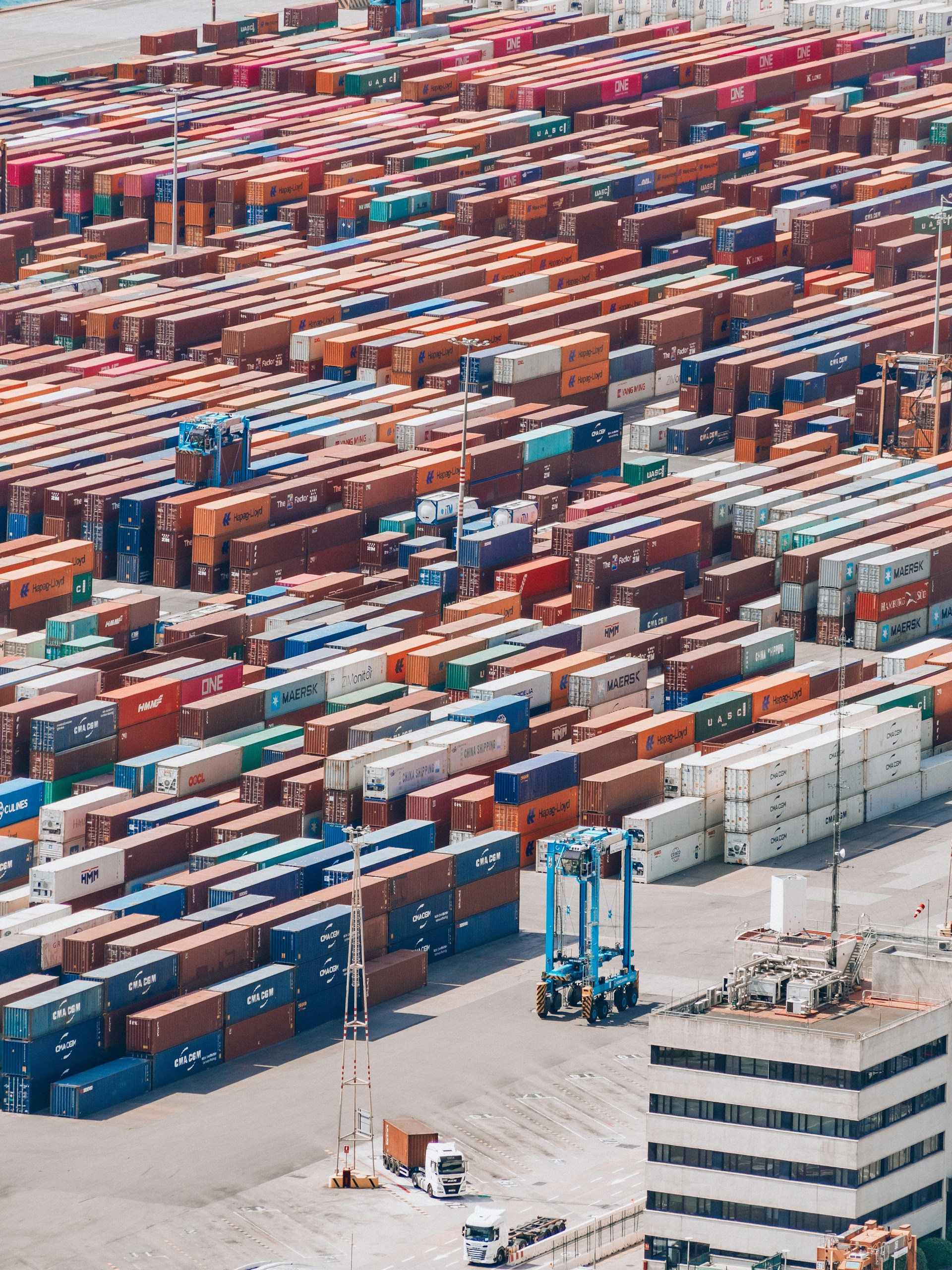

- The scale of business and commerce across the border—for example, in San Diego/Tijuana, Nogales/Nogales, El Paso/Ciudad Juárez, Laredo/Nuevo Laredo—as a counterweight to understanding the border only as a space of immigration and criminality.

Families and Children

- Migrant children and families have dominated much of the public discussion about the southwest border in recent years. The sheer increase in migrant families/children at the border over the last decade drives some of this emphasis. Commentaries have also considered as exceptional, even unprecedented, families with children, or children on their own, who are fleeing violence, persecution, or poverty across borders. The movement of children, with families or unaccompanied, across large territories and international borders, however, is not new at all. Hence the imperative of historical context to this conversation.

- History also helps us to understand why discussions about the border so often center on children. It isn’t just the numbers. This focus reflects influential cultural associations that link children with qualities of innocence, vulnerability, and the need for protection. Nothing imbues a political claim with more power than asserting that children are its victims or its beneficiaries. Historians have learned, however, that this sentimentalization of childhood can be a double-edged sword, often mobilized in ways that prove detrimental to parents—and even, paradoxically, to children themselves.

Exclusion and Restriction Policies

- Borders not only separate nations; they also bring nations and people closer together (via commerce, culture, communities). No border is entirely impermeable or impregnable. Unauthorized or “illegal” immigration is not an aberration but the inevitable result of any general policy of restriction. Historically, efforts to limit immigration have resulted in two streams of migration, lawful and unlawful (e.g., Chinese exclusion; 1924 quota act; 1965 and 1986 reform acts). We also tend to think about border control as applying only to our geographical borders. But 50 percent of the unauthorized population of 11 million in the United States are visa overstays.

- Before World War I, notwithstanding Chinese exclusion, immigration was regulated informally by the needs of the labor market, family unification, and protection from persecution. Beginning in 1924, these factors became subordinated to numerical restrictions.

- Historically, the United States has provided legalization programs to correct the problem of unauthorized immigration. Individual adjustments for Europeans in 1930s and ’40s; Chinese “confession” program in 1950s and 60s; general suspension of deportation after seven years of residence from 1952 through 1970s; mass regularization in 1986. But regularization has always been tied to enforcement aimed at stopping all future unauthorized entry, which does not work. Hence the cycle continues.

Participant Biographies

Geraldo Cadava is the Wender-Lewis Teaching and Research Professor of History at Northwestern University, and a contributing writer for The New Yorker. He is the author of The Hispanic Republican: The Shaping of an American Political Identity, from Nixon to Trump, and Standing on Common Ground: The Making of a Sunbelt Borderland. At present, he’s writing a book about Latino history over the past 500 years and how Latinos have always been both colonizers and colonized, to be published by Crown.

Nara Milanich is professor of Latin American history at Barnard College and director of the Center for Mexico and Central America at Columbia University. She researches the history of family, childhood, reproduction, gender, and law. She is the author of two award-winning books, Children of Fate: Childhood, Class, and the State in Chile, 1850–1930 and Paternity: The Elusive Quest for the Father. With Fanny García, she directs an oral history project called Separated: Stories of Injustice and Solidarity, which explores the life histories of Central American parents who were separated from their children at the US-Mexico border. Milanich has worked as a translator and legal assistant for migrant mothers and children incarcerated in the US’s largest immigrant detention center, located in Dilley, Texas.

Mae Ngai, Lung Family Professor of Asian American studies and professor of history at Columbia University, is one of the leading scholars of US immigration history. She is author of the award-winning books, Impossible Subjects (2004), on the origins of border enforcement, quotas, and illegal immigration in the 20th century; and The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics (2021), on Chinese exclusion policies in the US and in the British empire. She has written on immigration history and contemporary issues for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Atlantic, and other publications.