From the American Historical Review 47:4 (July 1942)

By William B. Hesseltine and Louis Kaplan1

I. Development of the American Ph. D. in History

From the colonial period to the middle of the nineteenth century, American colleges followed closely upon English models. The intellectual renaissance of the nineteenth century, hastened by political revolutions, Darwinism, and the Industrial Revolution, brought sweeping changes in American education. The questioning spirit, the decline of theology, and the rise of science brought an emphasis upon research. American universities began to assume responsibility for broadening the field of knowledge. Signalizing these changes, American universities borrowed the degree of doctor of philosophy from Germany.2

The first Americans to hold the Ph. D. in history studied at German universities. There they became familiar with the seminar method of instruction and received a new vision of a history which was not merely a branch of literature. Soon they brought the new vision and the new method to the United States. In 1876 Ephraim Emerton returned to Harvard with a Ph. D. from Leipzig, and Herbert Baxter Adams, with a Ph. D. from Heidelberg, began to teach in the newly established Johns Hopkins University. Already at Harvard, under the direction of Henry Adams, a group of students had begun work for the doctorate. In 1876 Henry Cabot Lodge received the Ph. D. in “History and Government” at Harvard. Two years later Henry C. Adams, the first product of H. B. Adams’s seminar at Hopkins, was awarded the Ph. D. Neither Lodge nor H. C. Adams was primarily a history graduate by present standards. The former would today be called a student in political science, the latter a student in economics. Both, however, received much of their training in history under teachers of history. Not until 1882, when John Franklin Jameson and Clarence Bowen received their doctorates from Johns Hopkins and Yale, respectively, was the American Ph. D. in history begun.

The creation of Johns Hopkins University marks the real beginnings of graduate study in the United States. Not only did the Baltimore university inspire imitation by other universities, but the Ph. D.’s whom Adams trained, teaching in colleges throughout the country, formed “colonies” which sent him a steady stream of new students already inspired by a zeal for historical research. By the end of the decade after Jameson received his degree, Adams had turned out thirty-eight doctors in history, among whom were such notable scholars as Charles H. Haskins, Woodrow Wilson, Frederick Jackson Turner, and Charles M. Andrews. During the same period, 1882–92, Harvard’s history department had conferred five Ph. D.’s; Columbia, beginning in 1885, had graduated three. Yale, which had had its first history Ph. D. in 1882, did not confer another until E. G. Bourne and F. W. Shepardson received their degrees in 1892. Pennsylvania gave its first Ph. D. in history in 1891 to William C. Scott, Minnesota in 1888 to Charles Burke Elliot. Wisconsin in 1893 conferred its first doctorate in history upon Kate Everest (Levi), the first such degree to be granted to a woman.

In these early days the history departments defined the requirements for the degree in vague terms. For the most part, they were content with an imitation of German practices and with the general definitions of the university faculties. The subject itself was narrowly conceived and dealt largely with so-called “institutional” history. At Harvard constitutional history dominated the field, with courses in 1890–91 in the constitutional history of England, the principles of constitutional law, medieval history, “with Special Reference to institutions”, early American institutions, constitutional development, and federal government.3 At Hopkins, Adams taught “institutional” history so exclusively that he wished his title to read “Professor of History and Institutions”. The titles of early dissertations as well as of the courses revealed this preoccupation with Verfassungsgeschichte. During the 1880’s at Columbia, theses on the “Constitutional History of Canada”, an “Outline of Anglo-Saxon Law”, a “History of the Law of Aliens”, “The Constitution of the United States in Civil War and Reconstruction”, indicated the legal and constitutional interest of candidates for the doctorate. At Johns Hopkins, Adams, believing that American governmental institutions had evolved from early Germanic germs, directed all his students into studies of local government. Legend has it that the professor, finally having exhausted the subjects in this narrow field, advised the members of his seminar to choose thesis subjects from European history. Legend further portrays the youthful Frederick Jackson Turner, scion of a Wisconsin pioneer, taking such patriotic offense at this attitude that he went forth to found the school of frontier history.

Certainly Turner’s epoch-making “Significance of the Frontier in American History” marked the beginning of a process of broadening the fields of history. At Wisconsin, Turner began to direct his students into the history of the American West. At Columbia, William A. Dunning began his famous seminar on the Reconstruction period, and Charles A. Beard, a few years later, began to call attention through his writings to American economic history. Those working in European history followed a similar evolution, moving from the institutions of the Middle Ages into modern European history and then into the peripheral areas of the Balkans, the Near East, and eventually to the Far East. The development of the foreign interests of the United States in the period of the World War brought South America into the widening horizon of the historian, and Latin-American history took its place beside the other fields of historical knowledge. The expanding interest of historians found also “social”, cultural, and agricultural history, the history of communications, of commerce, of journalism, of labor, and of public health. In all, by 1940 the American Historical Association classified the List of Doctoral Dissertations … in Progress into sixty categories. Through the laborious process of research on minute problems the boundaries of historical knowledge had been extended until Freeman’s dictum, which was inscribed upon the wall of the Johns Hopkins seminar—”History is past politics”—was only a memory.

The development of new fields of historical study was reflected in the evolution of the requirements for the Ph. D. In 1884, as young scholars began to seek his seminar, Herbert Baxter Adams drafted a program for the degree. The Ph. D. course, declared Adams, presupposed a general undergraduate knowledge of history. The candidate must also be able to read French and German and must have a knowledge of the historical literature in those languages. He must also attend lectures and seminars for ten to twelve hours a week and must be familiar with the original sources. The examinations for the degree would cover, first of all, the candidate’s principal subject, history, and two other subjects, such as international law and political economy. There should, too, be a thorough examination in a special field. Adams defined three: institutional history, which included the classic and the modern European states; church history; and the constitutional history of England and the United States. Having passed these examinations, the candidate might proceed in the seminar to work upon a “graduating thesis, which must be a positive contribution to special knowledge in the candidate’s chosen field”.4

For some years the Hopkins program was followed in other universities. So long as the students were few and the field of history narrow, the administration of the work for the degree presented no problems. With the growth of graduate school enrollments and with the historians’ widening horizons, however, new procedures became necessary. The most significant new procedure was the adoption of the preliminary examination. In the beginning Hopkins and several other universities used the M. A. degree as a testing ground for the doctoral candidate. The program for the M. A. resembled that for the Ph. D. The master’s essay gave a preliminary training in handling the took of research, while the final examination, written or oral, for the degree became the qualifying examination admitting to candidacy for the doctorate. The evolution of the M. A. into a degree for teachers—a development concurrent with the rise of Columbia University’s Teachers College—diluted the master’s degree as a test for a research program. Consequently the departments of history in the graduate schools began giving “preliminary” or qualifying examinations before admitting students as candidates for the Ph. D.

The fields of history in which the aspirant for admission to candidacy presents himself for examination have been variously defined. The facilities of the universities and the specialized interests of the history staff determined the definition of fields. In 1937–39 only the largest and best-equipped departments attempted a complete coverage of all the developed fields of historical study. Most departments contented themselves with specializing in the few fields for which library facilities were available. The presence of distinguished scholars in a particular field occasionally produced apparently incongruous combinations. In 1937–39 Harvard University led the list with forty-two fields from which the would-be doctor might select his specialties. At the other extreme, Yale offered only four. Harvard’s fields, divided into groups, included four relating to the ancient world and the Byzantine Empire, ten in periods of the history of European nations, two in American history, and one each in the history of Canada, Latin America, India, the Near East, and the Far East. Then, too, a variety of fields, which in most institutions would have been classified as “minor fields”, ranged from political theory, through Roman law and paleography, to anthropology and sociology. Literature, intellectual history, diplomatic history, and the history of religions all came within the scope of the Harvard program. Yale’s more limited statement defined the subjects for examination as medieval Europe and England, modern Europe, modern England and America. Between these extremes fell the other fifty-six universities offering the Ph. D. in history. Chicago and Minnesota each offered nineteen fields, of which only four—the ancient Orient, Greece, Rome, and Latin America—were defined in the same terms. Minnesota’s selection of two fields each in European and American economic history and one in Canadian history found no parallel at Chicago. Chicago’s two fields in Far Eastern history paralleled, but did not cover, Minnesota’s “Asia since 472”, while the “History of Russia” had no counterpart at Minnesota. Wisconsin in these years redefined its fields, changing from seven to fifteen. Brown University specified twelve fields, Ohio State sixteen, California nine, Northwestern ten, Columbia six, Michigan seven, and Pennsylvania fourteen.

Whatever may have been the limitations and classifications of the fields, all institutions gave basic training in ancient, medieval, and modern European history, and in English and American history. The candidate selected from three to six fields for examination. Each institution guided the selection by classifying the fields into groups and requiring the candidate to select fields which formed a logical unit. The “logic” in any given case depended upon the candidate’s intellectual equipment and his special research interests. In addition, the candidate had to offer one or two minor subjects in cognate fields of learning. Usually the examinations in the minors are administered by the departments concerned, but the selection is guided by the special interests of the candidate. History majors generally “take minors” in political science, economics, or sociology, though occasionally they may venture as far afield as literature or education. The general requirements of a “reading knowledge”—variously interpreted—of French and German, with the occasional substitution of another language for one of them, remained universal. Special requirements were sometimes added. Students of ancient history, for example, were generally required to possess more than a “reading knowledge” of the ancient tongues, while medievalists added diplomatics and paleography.

At first glance it would appear that the widening field of history had resulted in the adoption of the elective system by history departments. Yet in contrast to the elective system, the varied fields of history were unified both by technique and by philosophy. The seminars which trained Ph. D.’s in history might be narrow and the dissertations might be on obscure topics, yet the training in the techniques of research and the development of the philosophy of history had immense value to the whole intellectual progress of the nation.5

II. History Departments and Doctors of Philosophy

In 1939, within the continental United States, there were 1,688 institutions of higher learning. Many of these were so-called junior colleges, teachers colleges, or professional schools, but the large majority were colleges or universities of the traditional type. Almost without exception the colleges and universities offered the traditional four-year course for the bachelor’s degree, and a large proportion essayed some type of graduate instruction. In history, however, only fifty-eight universities offered—or had offered—a program leading to the Ph. D. This was less than 3 per cent of the total number of institutions, yet from the history departments of these fifty-eight universities had come over two thousand Ph. D.’s. Approximately 10 per cent of the total number of doctors of philosophy of American universities took their degrees in history.6

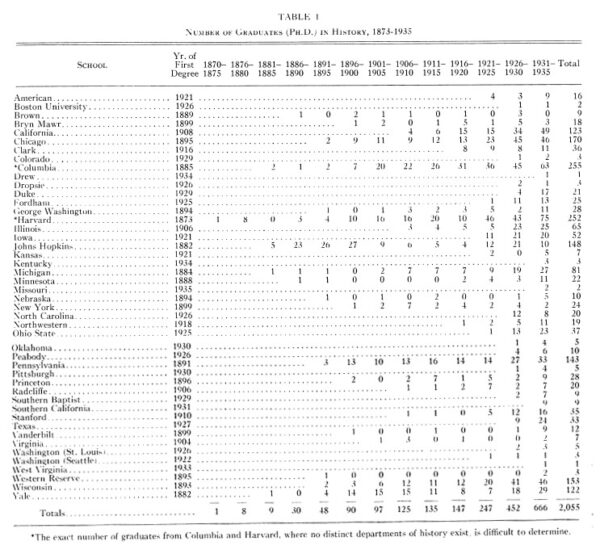

Among the fifty-eight graduate departments of history there were wide differences in the number of graduates. Of the 2,055 Ph. D.’s conferred between 1873 and 1935, six universities—Columbia, Harvard, Chicago, Wisconsin, Johns Hopkins, and Pennsylvania—granted 1,111 per cent; seventeen universities, granting less than ten degrees totaled but seventy-seven or 3.7 per cent. Few of these universities been in a position to grant the doctorate for the entire sixty-two years. For the first dozen years (1873–85) only Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Columbia, Michigan, and Yale conferred the doctorate in history. Of the eighteen recipients of, the degree in this period, nine worked at Harvard, five at Hopkins, two at Columbia, and one each at Michigan and Yale. During the next decade, eight more universities—Pennsylvania, Chicago, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Brown, George Washington, Nebraska, and Western Reserve—began to train Ph. D.’s in history. In this period Johns Hopkins took the lead, granting forty-nine of the seventy-eight degrees conferred. Harvard, in second place, gave the Ph. D. to seven candidates, and most of the newcomers conferred only one degree each. Between 1896 and 1905 sixteen universities conferred 187 Ph. D.’s in history; Hopkins, still in the lead, granted thirty-six; Yale, in second place, had twenty-nine; Columbia, Harvard, Pennsylvania, Chicago followed closely with twenty-seven, twenty-six, twenty-three, and twenty, respectively. Within the next ten years (1906-15) Hopkins, with only eleven, fell to eighth place, the lead being taken by Columbia, with forty-eight. Harvard conferred thirty-five, Pennsylvania twenty-nine, Yale twenty-six, Wisconsin twenty-three, and Chicago twenty-one. The number of departments conferring the degree rose to twenty, and the total degrees granted rose to 260.

From 1916 to 1925 the number of Ph. D.’s in history increased to 394. The decade was marked by the addition of California, with thirty graduates, to the list of the leading institutions. Columbia continued to grant the largest number of degrees (sixty-seven), followed by Harvard with fifty-six, Chicago with thirty-six, and Wisconsin with thirty-two. Twenty-seven departments gave at least one Ph. D. in these years. In the period from 1926 to 1935 the number of departments offering the doctorate more than doubled; while the total number of doctoral graduates leaped to 1,118. It was a period of increased undergraduate enrollment and of an increased demand for trained teachers and researchers. Moreover, a troubled world kept alive an interest in history. Perhaps through the study of the past might be found some key to the problems of the present.

Table 1 lists this growth by five-year periods. This table, as well as Table 2 and any discussion of these statistics, lacks data concerning eleven universities. The most important omissions are those of Cornell and Catholic University of America, the first of which refused and the second of which failed to furnish any data. In addition, the Biblical Seminary of New York, Boston College, Georgetown University, St. Louis University, Indiana University, Temple University, and the University of South Carolina appear to have granted the doctorate in history, at least in recent years. It may be assumed that the denominational institutions conferred the major portion of their degrees upon their clergy. The pamphlet Doctoral Dissertations accepted by American Universities, issued by the National Research Council, indicates that in the period 1925–35 Cornell conferred forty-seven doctorates in history, Catholic University forty, St. Louis twelve, Indiana eleven, Georgetown eight, Biblical Seminary four, Boston College four, South Carolina two, and Temple one. The system of classification adopted by this publication precludes any comparison with the present study.

III. Fields of Historical Research

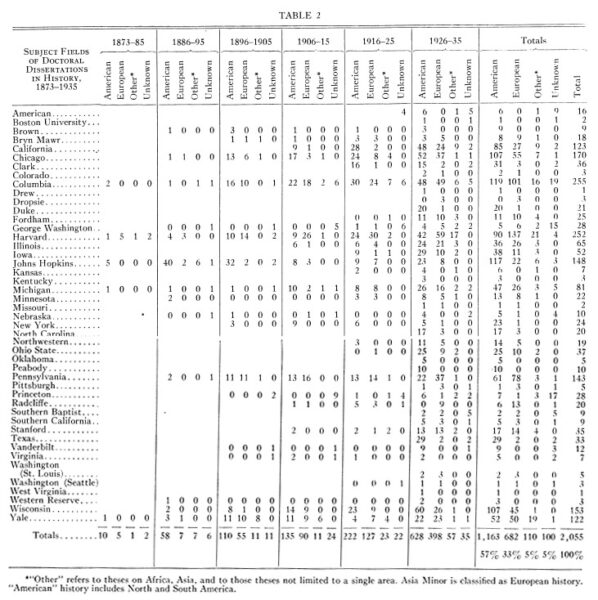

In selecting the fields for their first researches, a majority of Ph. D.’s have ignored the advice which H. B. Adams gave his seminar. Over half the candidates in history have selected theses subjects in American (United States and Latin-American) history. Only one third have elected to work in European history.

Although in the first twenty years of the doctorate in America nearly all the early teachers of graduate students in history had been trained in Europe, only 12 per cent of the candidates worked in European history. Since the beginning of the twentieth century nearly 40 per cent of the candidates have selected subjects outside the history of their native country. Among the larger universities, only Harvard and Pennsylvania have conferred more degrees in European than in American history, though Columbia has had an almost equal division between the two fields. Some of the smaller institutions, such as Bryn Mawr, Dropsie, George Washington, Pittsburgh, Radcliffe, Fordham, and Washington (St. Louis), have had most theses outside American history. Table 2 lists this distribution in ten-year periods.

IV. Occupations of Doctors of Philosophy in History

From the first, an overwhelming majority of holders of the Ph. D. in history have entered the teaching profession. The first students in the seminars at Johns Hopkins and Harvard were preparing for teaching careers. Occasionally one of them was enticed, like Henry Cabot Lodge, into journalism, politics, or public administration, and not infrequently one or another deserted the classroom for the larger salaries or more transitory importance of educational administration. “When the graduate school of history was first established”, declared Columbia’s Professor Carlton J. H. Hayes, “we did not contemplate that every recipient of the Ph. D. would enter teaching. The degree was, and should be, considered as an award to which any person in any profession who has great intellectual curiosity may aspire.”7 Yet the historian had found few’ other outlets for his talents, while the colleges furnished a steady “market” for the products of the seminars.

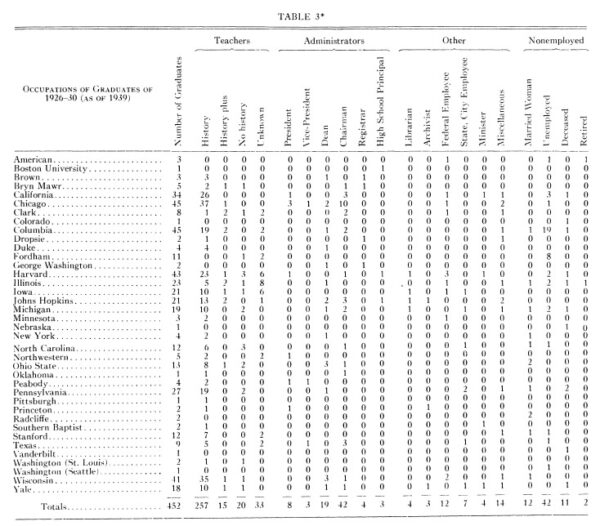

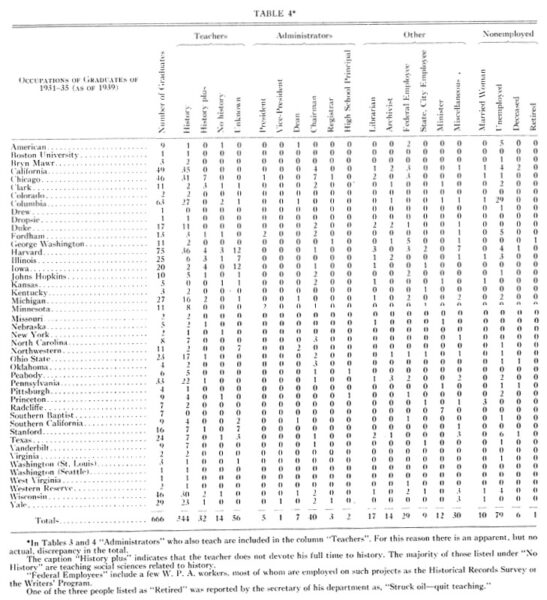

From 1926 to 1930 thirty-eight American universities conferred 452 Ph. D.’s in history. In the following five-year period, forty-five universities granted 666 doctor’s degrees. A comparison of these two groups indicates that 72 per cent of the former and 67 per cent of the latter had, in 1939, entered teaching. About the same percentage (14 per cent and 15 per cent) of each group was unemployed. Significance may attach to the increase of nonacademic employment, from 10 to 17 per cent, between the earlier and later groups. This figure may be accounted for in part by the impact of the depression upon college budgets.

It should be noted, however, that in recent years increasing numbers of history Ph. D.’s have been finding nonteaching positions in government service for which their training in history made them eligible. This has been especially true in the Federal government, which now employs about thirty-five history Ph. D.’s in the National Archives and considerable numbers in the National Park Service and the Historical Records Survey. A few are also employed for historical work by the Department of Agriculture and other agencies. State archival agencies, historical commissions, and the like are employing increasing numbers of Ph. D.’s in history, and a few are employed as archivists by private concerns such as railroad companies. The possible expansion of professional archival activities by states, municipalities, and corporations and the prospect that the National Archives will establish branches to care for the field records of Federal agencies may in the future solve the placement problem for a large number of history Ph. D.’s, especially if the universities provide specialized training in archives administration for

candidates interested in that field. Tables 3 and 4 list by institutions and by types of employment the occupations of graduates in these two five-year periods.

V. Teacher Placement of Doctors of Philosophy in History

Since the overwhelming majority of Ph. D.’s in history enter college and university teaching, graduate departments of history necessarily give considerable attention to “finding jobs” for their newly created doctors. Every graduate school keeps in close touch with the university’s teacher-placement bureau, and chairmen of history departments and advisers of students spend much time in assisting their fledgling Ph. D.’s to find suitable academic employment. Major professors advise their Ph. D. candidates to attend the annual meetings of the American Historical Association, the Mississippi Valley Historical Association, and the Pacific Coast Branch, in order to meet and interview prospective employers.

Persistent is the legend among the new doctors that “in the early days” the annual convocations of the historians were “slave markets”, where the new Ph. D. was welcomed into the gild and might pick his job from the rich offerings laid before him. From this legend springs a continuing pressure upon program chairmen for the opportunity to read papers at the meetings. The hope springs eternal that some department head, entranced by a display of energy and erudition, will—as in the days of yore—rush to the rostrum to offer at least an assistant professorship to the paper’s proud perpetrator! Alas for both legend and hope, few positions are obtained that way!

Perhaps, even in the beginning, the legend had small basis in fact. Herbert Baxter Adams devoted much of his time to placing his early graduates and proudly counted the “colonies” he had established. Yet even then placement was difficult. Few colleges had history departments, and fewer still wanted Ph. D.’s in history. Competition was keen for the few places that existed. Among the speculative “ifs” of history is the problem whether the world would have been different if young Woodrow Wilson had won the job at Kansas that went to Frank Hodder. And in the files of the department at Wisconsin is the evidence of a lively competition for an instructorship which finally went to Ulrich B. Phillips over Charles A. Beard.

Quite possibly the best period in the placement of Ph. D.’s in history was the decade following the World War. By that time the work of the accrediting agencies had had its effect in breaking down earlier prejudices against the Ph. D., while a sudden increase in undergraduate enrollments increased the demand. For a few brief years during and after the war the demand exceeded the supply. But the situation rapidly righted itself. The slow-grinding mills of the graduate schools speeded up—although probably they did not grind so fine—and the supply caught up with the demand at about the time the depression began to hit the college budgets.

The 1,686 colleges, junior colleges, teachers colleges, and technical schools of the United States constitute the “market” for the Ph. D.’s in history who enter the teaching profession. These colleges are distributed, roughly, throughout the United States in proportion to the population. Thanks to the work of the regional accrediting agencies, each region of the country employs its proper proportion of the output of the graduate departments of history. Thus, for example, New England, with about 7 per cent of the total population, has 8 per cent of the colleges and 6.5 per cent of the total number of college students in the country. By 1939, 8 per cent of those who had received Ph. D.’s in history from 1926 to 1935 had found academic employment in this region.

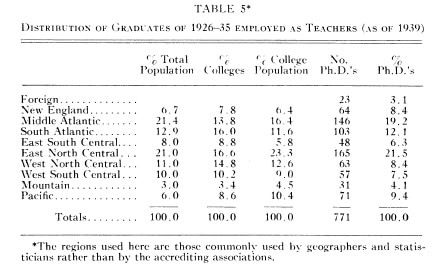

The following table lists, by percentages, the regional distributions in 1939 of 771 Ph. D.’s who received their degrees between 1925 and 1935 and entered the teaching field:

Although there is a fairly even distribution of Ph. D.’s over the entire “market”. the graduates of any given department tend to congregate in the immediate region of their home university. In 1939 46 per cent of the teaching Ph. D.’s who had received degrees between 1926 and 1935 were teaching in the region where they had done their graduate work. Thirty per cent were still in the same state. Even those who had found academic employment outside the home region had, for the most part, merely moved to an immediately adjacent region. Few graduates of the New England region made their way to the Pacific Coast, and in these ten years only one Ph. D. from the Coast found a place in New England.

Several factors combine to produce this phenomenal manifestation of academic provincialism. The absence of any national clearing house, or an employment agency supported by the profession, throws the burden of placement upon the chairmen and the major professors in the graduate departments. In a “buyers’ market” each chairman attempts to control the part of the market nearest him and where he can exert his greatest influence. Moreover, college presidents and deans usually insist that their teachers should be spiritually attuned to the region. They demand “Southerners who understand Southern people”, men who “understand the local situation” in the Middle West, or teachers who will not offend the delicate ears of New England students with the outlander’s harsh accents. Such requirements limit the field of selection. The result is regional inbreeding, with the ever-present threat of increasing the provincialism which a college education should combat.

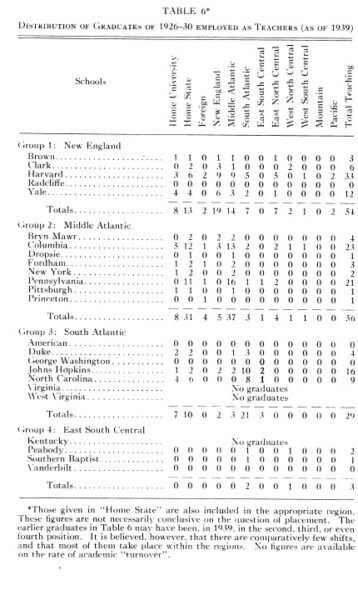

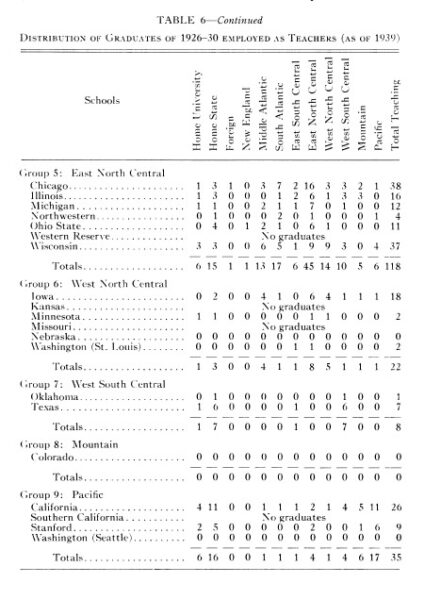

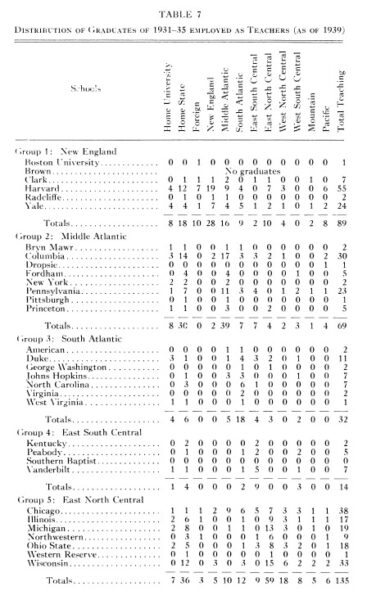

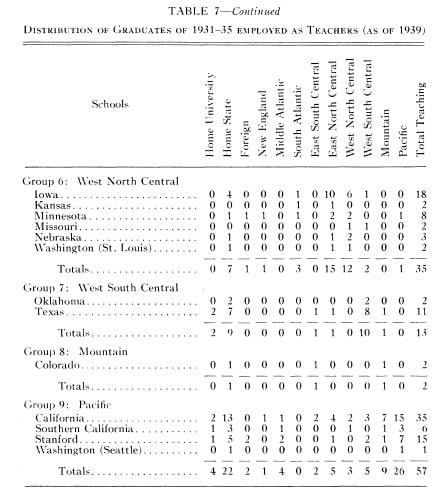

Equally significant of dangerous inbreeding is the large percentage of Ph. D.’s who find employment in the department where they did their graduate work. About 10 per cent of the doctors who received their degrees between 1926 and 1935 were teaching in their “home” university in 1939. Presumably these teachers fall into two classes: those too good to lose and those too bad to place but who are “taken care of” until some suitable employment appears. The placement figures for individual graduate departments of history are given in Tables 6 and 7.

VI. Productivity of Doctors of Philosophy in History

From the first years of the Ph. D. in America a curious controversy between “teaching” and “research” has waxed and waned in academic circles. The fact that a majority of doctors of philosophy have entered college teaching has given plausibility to perennial demands from college administrators, educationalists, and journalistic pundits that the universities should train teachers rather than researchers. Apparently the critics of the Ph. D. program, deceived by their own words, fail to perceive that teaching and learning are one and the same thing. The college teachers who are not actively engaged in contributing to their own knowledge and testing the results of their own researches by frequent publication are failing in their duty to their college, their students, and their profession.

The college official who fails to encourage his faculty’s researches or who emphasizes that he is seeking “good teachers, not research men” may be protecting his budget, but he is defrauding his patrons. Pressed by the accrediting agencies to maintain a minimum proportion of Ph. D.’s on his faculty, many a college president seeks only a nominal compliance with the requirement. Since laboratories, libraries, research facilities, and leaves of absence are expensive, college presidents deprecate research. The result defeats the purpose of the accrediting agencies.

Not only a desire for a cheap faculty, however, actuates the academic critics of research. Frequently a combination of gross ignorance and a fear of having his own incompetence exposed actuates the anti-research administrator. The dean who complained, when he asked for a man “who understood the teaching of science”, that a graduate school sent him a man who had “spent four years studying the reproduction of the earthworm”, obviously did not want a good teacher.8 He understood neither the meaning of biology nor the significance of the scientific method. Perhaps he found some glib and superficial popularizer of science, but he rejected a candidate who obviously was more likely to “understand the teaching of science”. Administrators who assert that “the high degree of specialization in study to which the Doctor of Philosophy has become accustomed is precisely that which is to be avoided in college teaching”9 seldom fail to call attention to the productivity of their faculties when reporting to their trustees or when approaching possible contributors to the endowment fund. Some of the catalogues of smaller colleges list the publications of the faculty in order to impress prospective students.

From still another direction have come attacks upon the researchers. Journalists, popularizers, and even novelists have taken up the glib refrain of the administrators and condemned the researches of the social scientists because of their dullness. Carlyle’s remarks on the “dry-as-dusts” have been mouthed by sundry popularizers whose own labors have consisted in skimming the cream from numerous monographs.

Historians, more intent upon publishing the results of researches for their fellows than on promulgating them with literary embellishments, have been the greatest sufferers from these critics. They have suffered doubly, for the poachers have not only stolen from them but have endeavored to cover their tracks by joining the cry against the Ph. D.’s.

The critics of the Ph. D.’s have failed to consider either the historical background or the social significance of the degree. From the time of its importation to America, the degree represented an intensive training in the methods of research. A majority of doctors of philosophy have worked in the sciences, and their researches have been fully utilized by industry. In an industrial nation, faced by complicated technical problems, the work of the trained researcher was of immediate social value. There was, of course, no reason why men who do such research could not have been trained in the industries which profited from them. Chemical manufacturers who have set up research laboratories might have trained their own staff of researchers. The electrical industries might have done the same. Hospitals might have continued to train doctors, and experienced lawyers might have taken in clerks to “read law” in their offices. Presumably, historical libraries and governmental archives could have produced researchers in history. But instead of the social demand for trained researchers being met by the industries and professions concerned, the colleges and universities took over the function. The Ph. D. became the label to mark the completion of an apprenticeship in research. The colleges assumed a new and broader function in a changing society; not only were they to pass down the traditional accomplishments which constituted an “education”, but they were also to participate in the adventure of broadening the boundaries of knowledge. The assumption of this new role brought with it increased endowments and a larger share of the public income.

The result of the verbal dichotomy which divides scholars into “teachers” and “research men” has been to de-emphasize research in the graduate schools. The dissertations of the doctors have been continued, but they are seldom published. The low status of research and the poor rewards have given excuses for the lazy, the incompetent, and the dilettanti to cease work. Such students enter the graduate schools to prepare for a “teaching” career. The achievement of the Ph. D. degree becomes the high point in their careers rather than the certificate of competence in research. Graduate departments, meeting the avowed needs of their “markets”, have announced that they were “teaching departments” and that their graduates were “teachers”.

Historians have been continually conscious of the criticisms directed against the Ph. D., and from time to time they have discussed their problems. At the 1904 meeting of the American Historical Association, Yale’s Professor George B. Adams proposed that the American doctorate be patterned on French rather than German practices and that the dissertation be abandoned. The majority of those participating in the discussion favored the retention of the dissertation. Professor C. M. Andrews pointed out that the printing of the dissertation improved the quality of the work. Others found defects in the program for the doctorate, and some deplored the low literary qualities of the dissertation, but only Wisconsin’s Professor Dana C. Munro agreed with Adams that the thesis was “not necessary for those seeking a broad scholarship”.

Whereas the dissertation has nowhere been abandoned and the requirement that it be published is general, so many evasive devices have been resorted to in recent years that publication has become the exception rather than the rule. The most common evasion is the publication of an “abstract” rather than of a substantial portion of the dissertation. Such abstracts may be sufficient in certain of the sciences, but the usual history thesis is both too long and too dependent upon the interpretation of detailed data to be satisfactorily abstracted. Only Columbia and the Catholic University make more than a feeble gesture to comply literally with the traditional rule of publication, and only Catholic University requires publication in full. In recent years experiments with such cheaper forms of publication as mimeographing, multigraphing, offset printing, hectographing, and microfilming offer some promise that the earlier practices may be restored.

Without the publication of the thesis there is no way that the historical profession can evaluate the work of either the new doctor or of the graduate department which has conferred the degree. Moreover, without publication the dissertation becomes, in the words of William Gardner Hale, merely a “piece of gymnastic apparatus, indifferent beyond id a show of the candidate’s strength”. In 1902 Hale addressed the assembled members of the Association of American Universities on the “Doctor’s s Dissertation”. The dissertation, he said,

… is a piece of property. If it is accepted, it is supposed to be a piece of property of some value. It is an intellectual possession, belonging to the writer—a part of the capital with which he starts upon his career. But its effectiveness lies wholly in publicity. If printed, it forms the writer’s best letter of introduction to the learned world at large, in his own particular field. If not printed, it is, as property, obliterated. … The knowledge that the dissertation, if accepted, is to be printed is inevitably an incentive to better work on the part of the writer. It can hardly seem to him of grave consequence to produce his best work, if its life is to be ephemeral, and even its grave unmarked.

Of the assembled deans who heard Hale, only two are on record as agreeing with him!10

Perhaps historians have been less assailed by the critics of the Ph. D. and have made saner adjustments to the criticism than the members of most other academic disciplines. In general, the graduate departments of history have insisted upon a broad training for doctoral candidates and have guided graduate researchers to subjects of more than minute significance. The gerund-grinding phase of historical research declined when the horizons began to broaden, and “institutional history” joined Freeman’s dictum in limbo. Yet historical research has suffered from the general anathemas against the Ph. D. The failure of college administrators to entourage research and the failure of the graduate departments to emphasize the value of continued productivity are partly responsible for the excessive number of “stillborn doctors” who do no work after receiving their degrees.

In 1927 Professor Marcus W. Jernegan, surveying the productivity of Ph. D.’s in history, concluded that only 25 per cent of the holders of the degree engaged in research. As obstacles to research he listed (1) low salaries, (2) lack of time, (3) nonacademic “services” which the communities demanded of teachers, (4) lack of library facilities, (5) lack of realization of suitable research topics, (6) cost of publishing. More serious than these, Professor Jernegan found that graduate instructors failed to stimulate a desire for research among their students and that a “low social value” was placed on research and publication.

Obviously, some of the “obstacles” which Professor Jernegan found were mere excuses for non-productiveness. The period of his study marked the highest point of academic salaries, and by that time the accrediting associations had succeeded in reducing the teaching load in the colleges to a point where a reasonable number of community services would not necessarily prohibit research. Moreover, the seasonal unemployment of academic people—euphoniously called summer vacations—added to the available time if not to the available funds for research. The geographical distribution of Ph. D.’s, half of whom live close enough to their alma maters to return for the homecoming game, makes “the lack of library facilities” more a plausible excuse than a valid reason for not engaging in research.11

In the years following Jernegan’s study,12 a larger number of graduate departments and young Ph. D’s began to strive to better the record. Aiding in the work of stimulating research were a number of forces. The American Historical Association created a revolving fund for the publication of meritorious work and began to issue check lists of research in progress. Other historical societies began to search for and publish monographs. Under the editorship of Professor Arthur C. Cole the Mississippi Valley Historical Review continued a process of broadening its interests until it covered the entire field of American history. Moreover, Editor Cole welcomed articles from new writers and offered freely his expert advice in improving the quality of their work. Other older magazines, many of which had declined to mere antiquarian and genealogical journals, followed this example and began to encourage new contributions.13 New historical journals and societies entered the field, such as the Business Historical Society Bulletin (1926), the Journal of Modern History and the East Tennessee Historical Society’s Publications (in 1929), Church History (1932), the Journal of Southern History, published by the Southern Historical Association (1935) and the American Military History Foundation Journal (1937), and offered new outlets for the products of research. New university presses—and new blood or spirit in older university presses—began to compete for good books with new processes of publication. The Social Science Research Council occasionally took cognizance of historical scholarships and handed out grants-in-aid, post-doctoral fellowships, or other encouraging emoluments to historians. The blue ribbon of a Guggenheim Fellowship has been conferred on a goodly number of historians. Perhaps, too, the depression helped make keener competition for jobs and recognition—the productive scholar had a competitive advantage over the stillborn doctor!

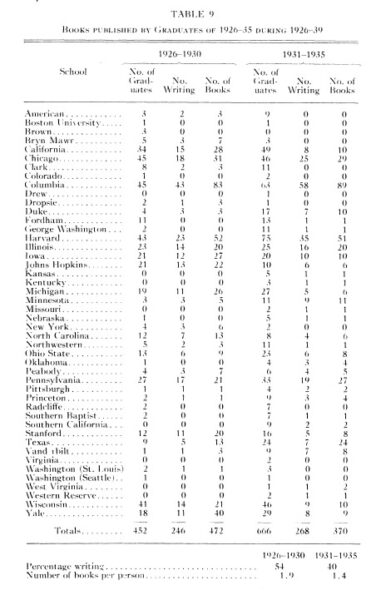

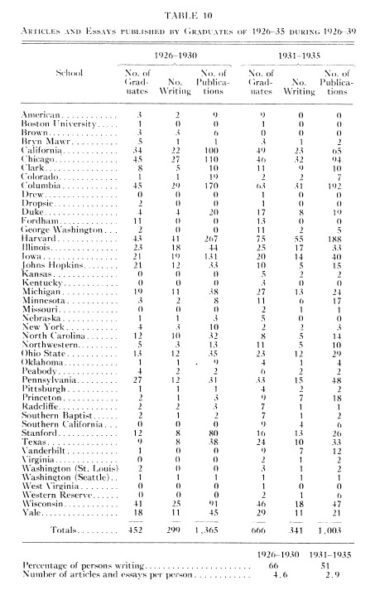

The result of these advantageous forces was the increase in the percentage of Ph. D.’s in history who were actively engaged in research and publication. Whereas in 1926 Professor Jernegan had found but 25 per cent of the Ph. D.’s engaged in research, over 50 per cent of those who received the degree in the next decade had publications to their credit and gave promise of continued productivity. By 1939 the 1,118 Ph. D.’s of 1926–35 had published nearly 2,500 articles in scholarly journals and over eight hundred books.

This was by far the best record of productivity which the Ph. D.’s in history had shown. Even in the first days of graduate work in history 50 per cent of the Ph. D.’s were unproductive. Of the forty-eight Ph. D.’s in history conferred by American universities between 1873 and 1891, one half had published nothing by 1902, while twenty-two had published articles and eighteen had published books. In those days, when the whole field of history was just beginning to be touched by scholarship, the number of books written by this pioneer group was forty-six and the number of articles 162. Per man, they were more productive than the eleven hundred Ph. D.’s of 1926–35, but the latter group had a larger percentage of their laborers toiling in the vineyard.14

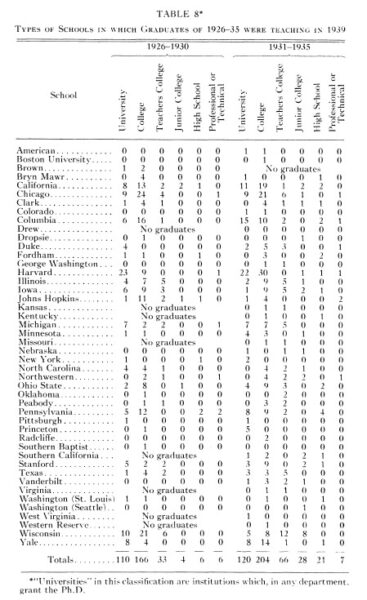

Not all of the graduate departments shared equally in this increased scholarly activity. Universities with active presses showed greater numbers of publications by their graduates than those without presses or with a poorly supported program of university publication. The universities which gave home and subsidy to scholarly periodicals produced, naturally, a greater number of productive scholars than those who did not hold such constant reminders before their students. In general, too, the larger departments graduated a higher percentage of producers than the smaller. Tables 9 and 10 list the productivity of the graduates of departments which conferred the Ph. D. between 1926 and 1935. These tables have been compiled from the following bibliographical sources: Writings on American History, 1925–35*; United States Catalog, 1925–39; Readers’ Guide, 1925–39; International Index to Periodicals, 1925–39; Bibliographic der fremdsprachigen Zeitschriftenliteratur, 1925–38; International Bibliography of Historical Sciences, 1926–36*; List of Doctoral Dissertations Printed, 1925–37*; Essay Index, 1925–38.15

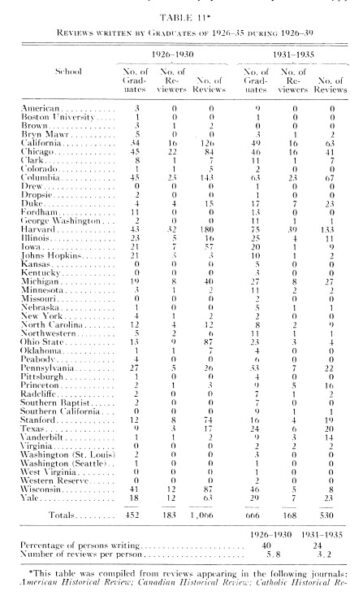

Although increased activity does not necessarily indicate improved quality, there are few historians of 1940 who would not contend that the average historical essay had improved in the sixty-four years since Herbert Baxter Adams organized his first seminar. Twice since Professor Jernegan’s article, the Pulitizer Prize in history has gone to doctoral dissertations. Though the literary standards of the Ph. D. remain low, an increasing number of productive scholars recognize the need for improvement. Through their researches the newer Ph. D.’s in history have gained the recognition of their scholarly fraternity. Some indication of the extent of this recognition may be obtained from the number of reviews which they are asked to do for the professional journals. Approximately one third of the graduates of 1926–35 had contributed reviews to the leading scholarly journals by 1939 (see Table 11).

In 1927 Professor Jernegan estimated that in the next ten years the universities would grant five hundred Ph. D.’s in history. He hoped that they would be of “much higher ability than the average at present”. If, of these five hundred, 50 per cent instead of 25 per cent become consistent producers, “then we may begin to hope for a new epoch in higher education in the United States”.16 Professor Jernegan’s estimate was too low, for more than 50 per cent of the next decade’s graduates had given promise of continuing productivity. Perhaps the new epoch is not beyond hope.

William B. Hesseltine

Louis Kaplan

University of Wisconsin

Notes

- In presenting these data on Ph. D.’s in history the writers wish to thank the chairmen of graduate departments of history and their secretaries who have been both generous and extremely co-operative in furnishing and checking lists of Ph. D.’s. In addition to the departmental chairmen, librarians, deans of graduate schools, and alumni secretaries have given valuable aid.

Such generous assistance has made possible the compilation of an almost complete list of Ph. D.’s in history. A few departments have inadequate records, and in some instances the writers have had to depend upon alumni lists. For the most part, these departments are small and have had but few graduates (see n. 6 below). The writers do not assume that they have either complete or strictly accurate data in any of the categories of this study, but they have used the greatest care in checking all available sources of information. The writers hope that errors and omissions will be called to their attention. They would, on their part, suggest that the American Historical Association publish annual lists of those receiving the Ph. D. in history. [↩]

- Yale conferred the first American Ph. D. in 1861. The University of Pennsylvania first gave the degree in 1870, Harvard in 1873, Columbia University’s School of Mines in 1875, Michigan in 1876, and Princeton in 1879. For information on the development of the Ph. D. see Walton C. John, Graduate Study in Universities and Colleges in the United States (Office of Education Bulletin, 1934, No. 20, Washington), pp. 20 ff. [↩]

- Samuel E. Morison, The Development of Harvard University (Cambridge, 1930), p. 462. [↩]

- W. Stull Holt, ed., Historical Scholarship in the United States, 1876–1901, as revealed in the Correspondence of Herbert B. Adams (Johns Hopkins University Studies Historical and Political Science, Series 56, No. 4, Baltimore, 1938), pp. 14–15. [↩]

- In this connection see id., “The Idea of Scientific History in America”, Journal of the History of Ideas, I, 352–62 (June, 1940). [↩]

- The compilations by Clarence S. Marsh in American Universities and Colleges (American Council on Education, Washington, 1936) would indicate that only chemistry and education conferred more doctorates, and that economics and English had equal numbers with history. The figures of this book, however, are so arranged that all d such as the J. D., the S. J. D., and Ed. D., are listed indiscriminately, and the demarcation between departments are not clearly drawn. [↩]

- New York Times, Apr. 2, 1939, in a news story entitled “Columbia strives to lift Standards in Higher Degrees”. [↩]

- The incident, probably fictitious, is related by B. Lamar Johnson in an essay entitled, “Needed: A Doctor’s Degree for General Education”, Journal of Higher Education X, 75–78 (Feb., 1939). Dean Johnson argues that specialized study “is not suited to the needs of teachers in general education”. [↩]

- New York Times, Dec. 18, 1939, quoting President Butler’s annual report. [↩]

- William Gardner Hale, “The Doctor’s Dissertation”, Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the Third Annual Conference of the Association of American Universities (1902), pp. 16 ff. [↩]

- Marcus W. Jernegan, “Productivity of Doctors of Philosophy in History“, American Historical Review, XXXIII, 1–22 (Oct., 1927). Few studies have been made of the productivity of Ph. D.’s in other subjects. Professor Jernegan’s figures might be compared with those given for doctors of education and for Ph. D.’s in mathematics. Walter S. Monroe and Arlyn Marks, in their article, “Doctors of Education”, Jour. Higher Educ., X, 191–94 (Apr., 1939), attempt to list both productivity and eminence in the profession for 986 Ed. D.’s of 1918–37. They found 66 per cent productive and about 30 per cent unproductive. For mathematics, R. G. D. Richardson, in his “The Ph. D. Degree and Mathematical Research”, American Mathematics Monthly, XLIII, 199–215 (Apr., 1936), estimated that 40 per cent of the graduates of 1915–25 had not, by 1936, published the results of their research. His study, however, included only papers read before the American Mathematical Society. [↩]

- Reprints still available in the Review office for ten cents to cover mailing. [↩]

- Note, for example, the evolution of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly and the transformation of the Washington Historical Quarterly into the Pacific Northwest Quarterly. [↩]

- This count is based on the Bibliography of Members of the American Historical Association, published as part of the Annual Report of 1902. Of the forty-eight doctors of philosophy in history whose degrees were conferred before 1891, forty-six were members of the Association; twenty-two of then listed no publications. [↩]

- More recent issues of the three sources marked with an asterisk were not at the time this study was under way. [↩]

- Jernegan, Am. Hist. Rev., XXXIII, 22. [↩]

Related Resources

March 31, 2008