Summary: A sizable majority of survey respondents equated “history” with nuts-and-bolts factual material as opposed to explanations about the past. That said, there are measurable differences in those views as a function of such factors as age and political affiliation. Moreover, those favoring an explanatory view of history showed signs of greater interest in, and perhaps empathy for, peoples and events far removed from the respondents.

Practicing historians probably have a good idea, even a sophisticated one, about what history is. But such definitions are likely complex and nuanced, and there is little reason to think that laypeople share them. A two-pronged goal of this survey was to determine how the public conceives of history and how such conceptions help shape other attitudes toward the past.

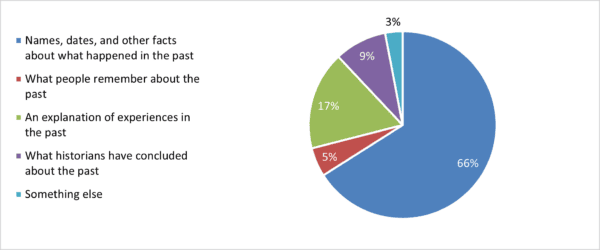

Given a selection of five possibilities, two-thirds of the poll’s respondents indicated a belief that history is primarily an assembly of names, dates, and other facts about what happened in the past (Figure 1). This belief is not strictly incorrect, insofar as basic facts serve as building blocks of serious historical inquiry. Similarly, laypersons are sometimes heavily reliant on professional historians’ interpretations of the past, especially for distant events where methods and language may constitute formidable roadblocks. In such cases, understandings of history depend greatly on what historians say about it.

Still, the public’s history-equals-facts outlook highlights a gulf between practicing historians and the audiences the former serve. While acknowledging the fundamental importance of facts, academics generally see history more as an explanation of past experiences. In fact, when Burkholder polled working historians and other professionals on this issue at a virtual AHA session in January 2021, the great majority selected the explanation’s definition, while nobody opted for facts. Yet only a small minority (17 percent) of those in the national survey shared professionals’ explanatory views (also Figure 1). Based on their survey from the 1990s, Rosenzweig and Thelen likewise perceived a disconnect between professional and amateur attitudes toward and uses of the past, suggesting that this dynamic remains largely unchanged in the aggregate. Subsequent studies by Sam Wineburg and others suggest that historians think about the past in fundamentally different ways than do nonhistorians, thus framing the issue as “historical thinking” as opposed to a basic mastery of factual material.

Figure 1: Survey respondents’ preferred best definitions for “history.” (D1)

Figure 1: Survey respondents’ preferred best definitions for “history.” (D1)

Lest respondents felt constrained by our five options, we included a text box to elicit alternative definitions or additional information from those who indicated that history is “something else.” Only 64 replied, meaning our sample is too small to draw any strong conclusions. Nevertheless, 15 of the responses (23 percent of the subset who offered additional information) indicated that history is some sort of combination of all the choices listed in the question. Several others used the open-ended option as an opportunity to voice a grievance. “History can be nothing more than lies and stories believed and written down as fact,” wrote one, while another opined that history is “written by the winners, most often neglecting to inform later readers of what or who else was affected.” Frustration with perceived subjectivity was evident. “History is the facts of the past without modern interpretations” is how one put it. Two others felt that history “is an incomplete view of the past, likely biased,” which “should be recorded without personal bias.” An additional response was emphatic that “History is what HAPPENED in the past, not what anyone thinks happened,” thereby eschewing any explanation component altogether.

A handful seemed to push the facts stance to an extreme, as when a respondent said that history encompasses “all things that have occurred before the present moment,” joined by another’s belief that anything from one second in the past “all the way to billions of years ago” is fair game. Countering that ecumenical view was a belief that history is “long enough ago to be able to see and understand the impact,” or, as another stated, “long enough in the past that the only real witnesses are dead.”

Other responses underscored the importance of evidence and human agency in making sense of it, often in quasi-scientific speak. These included “documented factual data” and people’s reactions to it, “recorded history and what can be deduced from science,” “a recording both written and oral,” or “what can be concluded from scientific research of the past.” Another small grouping saw history as a resource for the betterment of humankind, as seen in the field’s ability “to help us . . . understand human nature and improve over time.” As one more put it, “History is the opportunity to learn from our past successes and mistakes to improve our futures.”

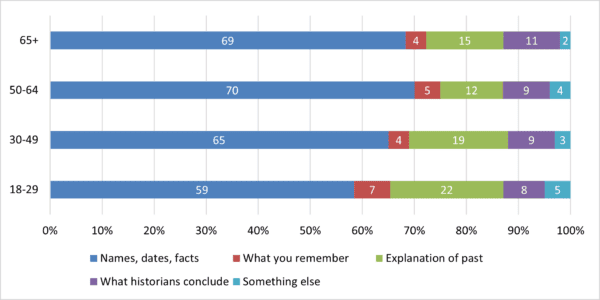

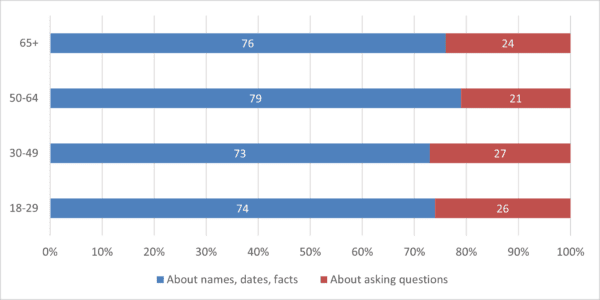

The importance of history-as-facts versus history-as-explanation outlooks becomes evident when considering cross-tabulations. Notably, one sees a certain amount of progress in breaching this divide as a function of age (Figure 2). Whereas 69 percent of those age 65+ and 70 percent of those 50–64 saw history mostly as raw facts, the numbers decline with younger cohorts: 65 percent for ages 30–49, dropping to 59 percent for ages 18–29 (though all of these remain majority figures). Meanwhile, there is a corresponding increase in those viewing history as an explanation as one moves down the age charts, from 15 percent in the 65+ group to 22 percent in the 18–29 one. Whether this is a function of curricular changes over the decades is not certain, though we note that there was broad agreement across age cohorts that high school history courses heavily favored factual command over asking questions about the past (Figure 3). College-level classes were not as skewed toward raw content, but even here, 44 percent of those surveyed said that names, dates, and facts predominated. This is further discussed in Section 6.

Figure 2: By age group: Respondents’ preferred best definitions for “history.” (D1)

Figure 2: By age group: Respondents’ preferred best definitions for “history.” (D1)

Figure 3: By age group: Respondents’ experiences in high school history courses. (V13)

Figure 3: By age group: Respondents’ experiences in high school history courses. (V13)

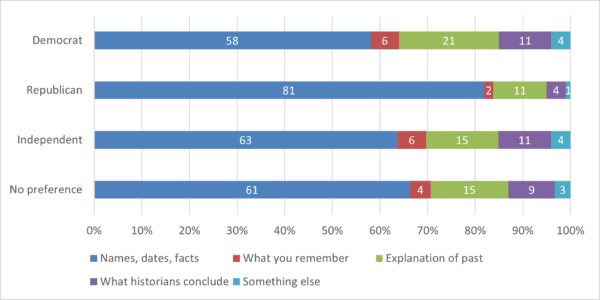

Political party identification likewise correlated with chosen definitions of history (Figure 4). A majority of respondents, whether self-identifying as Democrat, Republican, independent, or no preference, perceived history as defined by facts. That said, whereas Democrats, independents, and those with no preference all fell within a fairly narrow band of 58 percent to 63 percent agreement on this issue, Republicans skewed much more heavily (81 percent) toward a history-as-facts position. Political divisions also linked with beliefs that history is primarily an explanation of past events: whereas 21 percent of Democrats supported that viewpoint, only 11 percent of Republicans did. The latter group was also far less likely to see historians’ interpretations as authoritative.

Figure 4: By political party: Respondents’ preferred best definitions for “history.” (D1)

Figure 4: By political party: Respondents’ preferred best definitions for “history.” (D1)

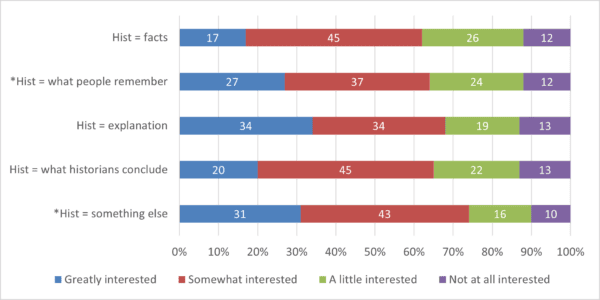

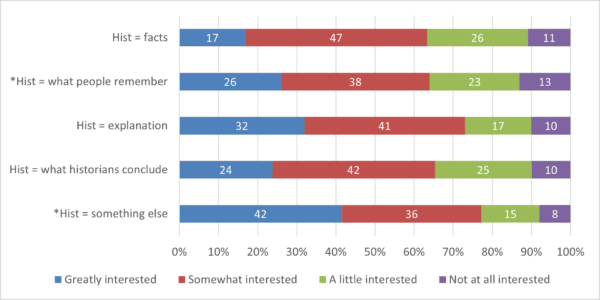

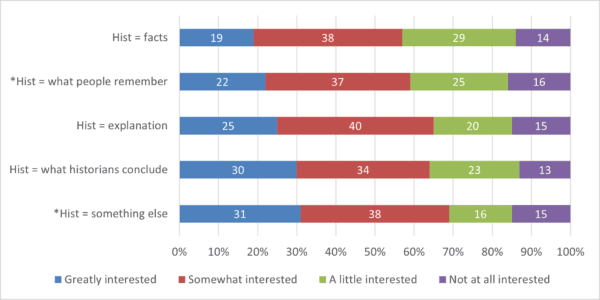

A heightened curiosity about the wider world corresponded with a belief that history explains the past, as opposed to merely describing that past via factual recall. Those seeing history as explanation were twice as likely (34 percent versus 17 percent) to indicate great interest in learning about the histories of foreign places or peoples (Figure 5). Such trends carried over, though to lesser extents, to greater interest in persons perceived as different from the respondents (32 percent versus 17 percent; Figure 6) and in events from over 500 years ago (25 percent versus 19 percent; Figure 7).

Figure 5: Respondents’ interest in learning more about histories of foreign places or peoples as a function of perceptions of history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (D1 x S7)

Figure 5: Respondents’ interest in learning more about histories of foreign places or peoples as a function of perceptions of history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (D1 x S7)

Figure 6: Respondents’ interest in learning more about people perceived as different as a function of perceptions of history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (D1 x S7)

Figure 6: Respondents’ interest in learning more about people perceived as different as a function of perceptions of history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (D1 x S7)

Figure 7: Respondents’ interest in learning more about history over 500 years ago as a function of perceptions of history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (D1 x S7)

Figure 7: Respondents’ interest in learning more about history over 500 years ago as a function of perceptions of history. *Fewer than 100 responses. (D1 x S7)

Challenges and opportunities: The public’s persistent view of “history” as mostly an assembly of facts results in a simplistic understanding of the past, one that is at odds with that of practicing historians. Overcoming this impasse is both important and difficult, given the public’s long-standing outlook and an education system that often reinforces simplicity. Nevertheless, there are signs of an appetite for history-as-inquiry, which results in not only a better understanding of the past, but increased interest in the broader world.