This presidential address was delivered at the 94th annual meeting of the American Historical Association in New York, December 28, 1979. Published in the American Historical Review 85, no. 1 (Feb., 1980), pp. 1-14

Mirror for Americans: A Century of Reconstruction History

Perhaps no human experience is more searing or more likely to have a long-range adverse effect on the participants than violent conflict among peoples of the same national, racial, or ethnic group. During the conflict itself the stresses and strains brought on by confrontations ranging from name-calling to pitched battles move people to the brink of mutual destruction. The resulting human casualties as well as the physical destruction serve to exacerbate the situation to such a degree that reconciliation becomes virtually impossible. The warring participants, meanwhile, have done irreparable damage to their common heritage and to their shared government and territory through excessive claims and counterclaims designed to make their opponents’ position appear both untenable and ludicrous.

Situations such as these have occurred throughout history; they are merely the most extreme and most tragic of numerous kinds of conflicts that beset mankind. As civil conflicts—among brothers, compatriots, coreligionists, and the like—they present a special problem not only in the prosecution of the conflict itself but in the peculiar problems related to reconciliation once the conflict has been resolved. One can well imagine, for example, the utter bitterness and sense of alienation that both sides felt in the conflict that marked the struggle for power between the death in 1493 of Sonni Ali, the ruler of the Songhay empire, and the succession of Askia Muhammad some months later. The struggle was not only between the legitimate heir and an army commander but also between the traditional religion and the relatively new, aggressive religion of Islam, a struggle in which the military man and his new religion emerged victorious.1

Historians have learned a great deal about these events, although they are wrapped in the obscurity and, indeed, the evasive strategies of the late Middle Ages. Despite the bitterness of the participants in the struggle and the dissipating competition of scholars in the field, we have learned much more about the internal conflicts of the Songhay empire of West Africa and about the details of Askia Muhammad’s program of reconstruction than we could possibly have anticipated—either because the keepers of the records were under his influence or because any uncomplimentary accounts simply did not survive. Interestingly enough, however, the accounts by travelers of the energetic and long-range programs of reconstruction coincide with those that the royal scribes provided.2

Another example of tragic internal conflict is the English Civil War of the seventeenth century. The struggle between Charles I and those who supported a radical Puritan oligarchy led not only to a bloody conflict that culminated in the execution of the king but also to bizarre manifestations of acrimony that ranged from denouncing royalism in principle to defacing icons in the churches. Not until the death of Oliver Cromwell and the collapse of the Protectorate were peace and order finally achieved under Charles II, whose principal policies were doubtless motivated by his desire to survive. The king’s role in the reconstruction of England was limited; indeed, the philosophical debates concerning, as well as the programs for, the new society projected by the Protectorate had a more significant impact on England’s future than the restoration of the Stuarts had.

Thanks to every generation of scholars that has worked on the English Civil War and its aftermath, we have had a succession of illuminations without an inordinate amount of heat. Granted, efforts to understand the conflict have not always been characterized by cool objectivity and generous concessions. But, because historians have been more concerned with understanding the sources than with prejudging the events with or without the sources, we are in their debt for a closer approximation to the truth than would otherwise have been the case.3

I daresay that both the Africanists concerned with Songhay and the students of the English Civil War will scoff at these general statements, which they may regard as a simplistic view of the struggles that they have studied so intensely. I am in no position to argue with them. The point remains that, whether one views the internal conflicts of the people of Songhay in the fifteenth century, the English in the seventeenth century, or the Americans in the nineteenth century, the conflict itself was marked by incomparable bitterness and extensive bloodshed. The aftermath, moreover, was marked by continuous disputation over the merits of the respective cases initially as well as over the conduct of the two sides in the ensuing years. These continuing disputations, it should be added, tell as much about the times in which they occurred as about the period with which they are concerned. And, before I do violence either to the facts themselves or to the views of those who have studied these events, I shall seek to establish my claim in the more familiar environment of the aftermath of the Civil War in the United States.

In terms of the trauma and the sheer chaos of the time, the aftermath of the American Civil War has few equals in history. After four years of conflict the burden of attempting to achieve a semblance of calm and equanimity was almost unbearable. The revolution in the status of four million slaves involved an incredible readjustment not only for them and their former owners but also for all others who had some understanding of the far-reaching implications of emancipation. The crisis in leadership occasioned by the assassination of the president added nothing but more confusion to a political situation that was already thoroughly confused. And, as in all similar conflicts, the end of hostilities did not confer a monopoly of moral rectitude on one side or the other. The ensuing years were characterized by a continuing dispute over whose side was right as well as over how the victors should treat the vanquished. In the post-Reconstruction years a continuing argument raged, not merely over how the victors did treat the vanquished but over what actually happened during that tragic era.

If every generation rewrites its history, as various observers have often claimed, then it may be said that every generation since 1870 has written the history of the Reconstruction era. And what historians have written tells as much about their own generation as about the Reconstruction period itself. Even before the era was over, would-be historians, taking advantage of their own observations or those of their contemporaries, began to speak with authority about the period.

James S. Pike, the Maine journalist, wrote an account of misrule in South Carolina, appropriately called The Prostrate State, and painted a lurid picture of the conduct of Negro legislators and the general lack of decorum in the management of public affairs.4 Written so close to the period and first published as a series of newspaper pieces, The Prostrate State should perhaps not be classified as history at all. But for many years the book was regarded as authoritative—contemporary history at its best.5 Thanks to Robert Franklin Durden, we now know that Pike did not really attempt to tell what he saw or even what happened in South Carolina during Reconstruction. By picking and choosing from his notes those events and incidents that supported his argument, he sought to place responsibility for the failure of Reconstruction on the Grant administration and on the freedmen, whom he despised with equal passion.6

A generation later historians such as William Archibald Dunning and those who studied with him began to dominate the field. Dunning was faithfully described by one of his students as “the first to make scientific and scholarly investigation of the period of Reconstruction.”7 Despite this evaluation, he was as unequivocal as the most rabid opponent of Reconstruction in placing upon Scalawags, Negroes, and Northern radicals the responsibility for making the unworthy and unsuccessful attempt to reorder society and politics in the South.8 His “scientific and scholarly” investigations led him to conclude that at the close of Reconstruction the planters were ruined and the freedmen were living from hand to mouth—whites on the poor lands and “thriftless blacks on the fertile lands.”9 No economic, geographic, or demographic data were offered to support this sweeping generalization.

Dunning’s students were more ardent than he, if such were possible, in pressing their case against Radical Republicans and their black and white colleagues. Negroes and Scalawags, they claimed, had set the South on a course of social degradation, misgovernment, and corruption. This tragic state of affairs could be changed only by the intervention of gallant men who would put principle above everything else and who, by economic pressure, social intimidation, and downright violence, would deliver the South from Negro rule. Between 1900 and 1914 these students produced state studies and institutional monographs that gave more information than one would want about the complexion, appearance, and wearing apparel of the participants and much less than one would need about problems of postwar adjustment, social legislation, or institutional development.10

Perhaps the most important impact of such writings was the influence they wielded on authors of textbooks, popular histories, and fiction. James Ford Rhodes, whose general history of the United States was widely read by contemporaries, was as pointed as any of Dunning’s students in his strictures on Reconstruction: “The scheme of Reconstruction,” he said, “pandered to ignorant negroes, the knavish white natives, and the vulturous adventurers who flocked from the North. …”11 Thomas Dixon, a contemporary writer of fiction, took the findings of Rhodes’s and Dunning’s students and made the most of them in his trilogy on Civil War and Reconstruction. In The Clansman, published in 1905, he sensationalized and vulgarized the worst aspects of the Reconstruction story, thus beginning a lore about the period that was dramatized in Birth of a Nation, the 1915 film based on the trilogy, and popularized in 1929 by Claude Bowers in The Tragic Era.12

Toward the end of its most productive period the Dunning school no longer held a monopoly on the treatment of the Reconstruction era. In 1910 W. E. B. DuBois published an essay in the American Historical Review entitled, significantly, “Reconstruction and Its Benefits.” DuBois dissented from the prevailing view by suggesting that something good came out of Reconstruction, such as educational opportunities for freedmen, the constitutional protection of the rights of all citizens, and the beginning of political activity on the part of the freedmen. In an article published at the turn of the century, he had already hinted “that Reconstruction had a beneficial side,” but the later article was a clear and unequivocal presentation of his case.13

DuBois was not the only dissenter to what had already become the traditional view of Reconstruction. In 1913 a Mississippi Negro, John R. Lynch, former speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives and former member of Congress, published a work on Reconstruction that differed significantly from the version that Mississippi whites had accepted. Some years later he argued that a great deal of what Rhodes had written about Reconstruction was “absolutely groundless.” He further insisted that Rhodes’s account of Reconstruction was not only inaccurate and unreliable but was “the most one-sided, biased, partisan, and prejudiced historical work” that he had ever read.14 A few years later Alrutheus A. Taylor published studies of the Negro in South Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee, setting forth the general position that blacks during Reconstruction were not the ignorant dupes of unprincipled white men, that they were certainly not the corrupt crowd they had been made out to be, and that their political influence was quite limited.15

The most extensive and, indeed, the most angry expression of dissent from the well-established view of Reconstruction was made in 1935 by W. E. B. DuBois in his Black Reconstruction. “The treatment of the period of Reconstruction reflects,” he noted, “small credit upon American historians as scientists.” Then he recalled for his readers the statement on Reconstruction that he wrote in an article that the Encyclopedia Britannica had refused to print. In that article he had said, “White historians have ascribed the faults and failures of Reconstruction to Negro ignorance and corruption. But the Negro insists that it was Negro loyalty and the Negro vote alone that restored the South to the Union, established the new democracy, both for white and black, and instituted the public schools.”16 The American Historical Review did no better than the Encyclopedia Britannica, since no review of Black Reconstruction, the first major scholarly work on Reconstruction since World War I, appeared in the pages of the Review. The work was based largely on printed public documents and secondary literature because, the author admitted, he lacked the resources to engage in a full-scale examination of the primary materials17 and because DuBois thought of his task as the exposure of the logic, argument, and conclusions of those whose histories of Reconstruction had become a part of the period’s orthodoxy. For this task he did not need to delve deeply into the original sources.

From that point on, works on Reconstruction represented a wide spectrum of interpretation. Paul Herman Buck’s Road to Reunion shifted the emphasis to reconciliation, while works by Horace Mann Bond and Vernon L. Wharton began the program of fundamental and drastic revision.18 No sooner was revisionism launched, however, than E. Merton Coulter insisted that “no amount of revision can write away the grievous mistakes made in this abnormal period of American history.” He then declared that he had not attempted to do so, and with that he subscribed to virtually all of the views that had been set forth by the students of Dunning. And he added a few observations of his own, such as “education soon lost its novelty for most of the Negroes”; they would “spend their last piece of money for a drink of whisky”; and, being “by nature highly emotional and excitable … , they carried their religious exercises to extreme lengths.”19

By mid-century, then, there was a remarkable mixture of views of Reconstruction by historians of similar training but of differing backgrounds, interests, and commitments. Some were unwilling to challenge the traditional views of Reconstruction. And, although their language was generally polite and professional, their assumptions regarding the roles of blacks, the nature of the Reconstruction governments in the South, and the need for quick—even violent—counteraction were fairly transparent. The remarkable influence of the traditional view of Reconstruction is nowhere more evident than in a work published in 1962 under the title Texas under the Carpetbaggers. The author did not identify the carpetbaggers, except to point out that the governor during the period was born in Florida and migrated to Texas in 1848 and that the person elected to the United States Senate had been born in Alabama and had been in Texas since 1830.20 If Texas was ever under the carpetbaggers, the reader is left to speculate about who the carpetbaggers were! Meanwhile, in the 1960s one of the most widely used college textbooks regaled its readers about the “simple-minded” freedmen who “insolently jostled the whites off the sidewalks into the gutter”; the enfranchisement of the former slaves set the stage for “stark tragedy,” the historian continued, and this was soon followed by “enthroned ignorance,” which led inevitably to “a carnival of corruption and misrule.”21 Such descriptions reveal more about the author’s talent for colorful writing than about his commitment to sobriety and accuracy.

Yet an increasing number of historians began to reject the traditional view and to argue the other side or, at least, to insist that there was another side. Some took another look at the states and rewrote their Reconstruction history. In the new version of Reconstruction in Louisiana the author pointed out that “the extravagance and corruption for which Louisiana Reconstruction is noted did not begin in 1868,” for the convention of 1864 “was not too different from conventions and legislatures which came later.”22 Others looked at the condition of the former slaves during the early days of emancipation and discovered that blacks faced freedom much more responsibly and successfully than had hitherto been described. Indeed, one student of the problem asserted that “Reconstruction was for the Negroes of South Carolina a period of unequaled progress.”23 Still others examined institutions ranging from the family to the Freedmen’s Savings Bank and reached conclusions that were new or partly new to our understanding of Reconstruction history.24 Finally, there were the syntheses that undertook, unfortunately all too briefly, to make some overall revisionist generalizations about Reconstruction.25

Up to this point my observations have served merely as a reminder of what has been happening to Reconstruction history over the last century. I have not intended to provide an exhaustive review of the literature. There have already been extensive treatments of the subject, and there will doubtless be more.26 Reconstruction history has been argued over and fought over since the period itself ended. Historians have constantly disagreed not only about what significance to attach to certain events and how to interpret them but also (and almost as much) about the actual events themselves. Some events are as obscure and some facts are apparently as unverifiable as if they dated from several millennia ago. Several factors have contributed to this state of affairs. One factor, of course, is the legacy of bitterness left behind by the internal conflict. This has caused the adversaries—and their descendants—to attempt to place the blame on each other (an understandable consequence of a struggle of this nature). Another factor is that the issues have been delineated in such a way that the merits in the case have tended to be all on one side. A final factor has been the natural inclination of historians to pay attention only to those phases or aspects of the period that give weight to the argument presented. This inclination may involve the omission of any consideration of the first two years of Reconstruction in order to make a strong case against, for example, the Radicals. Perhaps such an approach has merit in a court of law or in some other forum, but as an approach to historical study its validity is open to the most serious question.

Perhaps an even more important explanation for the difficulty in getting a true picture of Reconstruction is that those who have worked in the field have been greatly influenced by the events and problems of the period in which they were writing. That first generation of students to study the postbellum years “scientifically” conducted its research and did its writing in an atmosphere that made the conclusions regarding Reconstruction foregone. Different conclusions were inconceivable.27 Writing in 1905 Walter L. Fleming referred to James T. Rapier, a Negro member of the Alabama constitutional convention of 1867, as “Rapier of Canada.” He then quoted Rapier as saying that the manner in which “colored gentlemen and ladies were treated in America was beyond his comprehension.”28

Born in Alabama in 1837, Rapier, like many of his white contemporaries, went North for an education. The difference was that instead of stopping in the northern part of the United States, as, for example, William L. Yancey did, Rapier went on to Canada. Rapier’s contemporaries did not regard him as a Canadian; and, if some were not precisely clear about where he was born (as was the Alabama State Journal, which referred to his birthplace as Montgomery rather than Florence), they did not misplace him altogether.29 In 1905 Fleming made Rapier a Canadian because it suited his purposes to have a bold, aggressive, “impertinent” Negro in Alabama Reconstruction come from some non-Southern, contaminating environment like Canada. But it did not suit his purposes to call Yancey, who was a graduate of Williams College, a “Massachusetts Man.” Fleming described Yancey as, simply, the “leader of the States Rights men.”30

Aside from his Columbia professors, Fleming’s assistance came largely from Alabamians: Thomas M. Owen of the Department of Archives and History, G. W. Duncan of Auburn, W. W. Screws of the Montgomery Advertiser, and John W. Du Bose, Yancey’s biographer and author of Alabama’s Tragic Decade.31 At the time that Fleming sought their advice regarding his Reconstruction story, these men were reaping the first fruits of disfranchisement, which had occurred in Alabama in 1901. Screws’s Advertiser had been a vigorous advocate of disfranchisement, while Du Bose’s Yancey, published a decade earlier, could well have been a campaign document to make permanent the redemption of Alabama from “Negro-carpetbagger-Scalawag rule.”32 It is inconceivable that such men would have assisted a young scholar who had any plans except to write an account of the Reconstruction era that would support their views. In any case they could not have been more pleased had they written Fleming’s work for him.

But the “scientific” historians might well have been less pleased if they had not been caught up in the same pressures of the contemporary scene that beset Fleming. They, like Fleming, should have been able to see that some of the people that Fleming called “carpetbaggers” had lived in Alabama for years and were, therefore, entitled to at least as much presumption of assimilation in moving from some other state to Alabama decades before the war as the Irish were in moving from their native land to some community in the United States. Gustavus Horton, a Massachusetts “carpetbagger” and chairman of the constitutional convention’s Committee on Education in 1867, was a cotton broker in Mobile and had lived there since 1835. Elisha Wolsey Peck, the convention’s candidate for chief justice in 1867, moved to Alabama from New York in 1825. A few months’ sojourn in Illinois in 1867convinced Peck that the only real home he could ever want was Alabama. Charles Mayes Cabot, a member of the constitutional convention of 1865as well as of the one of 1867, had come to Alabama from his native Vermont as a young man. He prospected in the West in 1849 but was back in Wetumka in the merchandising business by 1852.33 Whether they had lived in Alabama for decades before the Civil War or had settled there after the war, these “carpetbaggers” were apparently not to be regarded as models for Northern investors or settlers in the early years of the twentieth century. Twentieth-century investors from the North were welcome provided they accepted the established arrangements in race relations and the like. Fleming served his Alabama friends well by ridiculing carpetbaggers, even if in the process he had to distort and misrepresent.

In his study of North Carolina Reconstruction published in 1914, Joseph G. de Roulhac Hamilton came as close as any of his fellow historians to reflecting the interests and concerns of his own time. After openly bewailing the enfranchisement of the freedmen, the sinister work of the “mongrel” convention and legislatures, and the abundance of corruption, Hamilton concluded that Reconstruction ‘was a crime that is “to-day generally recognized by all who care to look the facts squarely in the face.” But for Reconstruction, he insisted, “the State would to-day, so far as one can estimate human probabilities, be solidly Republican. This was clearly evident in 1865, when the attempted restoration of President Johnson put public affairs in the hands of former Whigs who then had no thought of joining in politics their old opponents, the Democrats.” Hamilton argued that in his own time some men who regularly voted the Democratic ticket would not call themselves “Democrats.” In an effort to appeal to a solid Negro vote, the Republicans had lost the opportunity to bring into their fold large numbers of former Whigs and some disaffected Democrats. In the long run the Republicans gained little, for the Negroes, who largely proved to be “lacking in political capacity and knowledge, were driven, intimidated, bought, and sold, the playthings of politicians, until finally their so-called right to vote became the sore spot of the body politic.”34 In his account of Reconstruction, which placed the blame on the Republican-Negro coalition for destroying the two-party system in North Carolina, Hamilton gave a warning to his white contemporaries to steer clear of any connection with blacks whose votes could be bought and sold if the franchise were again extended to them.

And the matter was not only theoretical. In 1914, while Hamilton was writing about North Carolina Reconstruction, Negro Americans were challenging the several methods by which whites had disfranchised them, and Hamilton was sensitive to the implications of the challenge. He reminded his readers that, after the constitutional amendment of 1900 restricting the suffrage by an educational qualification and a “grandfather clause,” the Democrats elected their state ticket. His eye was focused to a remarkable degree on the current political and social scene. “The negro has largely ceased to be a political question,” he commented, “and there is in the State to-day as a consequence more political freedom than at any time since Reconstruction.”35 The lesson was painfully clear to him, as he hoped it would be to his readers: the successful resistance to the challenges that Negroes were making to undo the arrangements by which they had been disfranchised would remove any fears that whites might have of a repetition of the “crime” of Reconstruction. Segregation statutes, the white Democratic primary, discrimination in educational opportunities, and, if necessary, violence were additional assurances that there would be no return to Reconstruction.

Unfortunately, the persistence of the dispute over what actually happened during Reconstruction and the use of Reconstruction fact and fiction to serve the needs of writers and their contemporaries have made getting at the truth about the so-called Tragic Era virtually impossible. Not only has this situation deprived the last three generations of an accurate assessment of the period but it has also unhappily strengthened the hand of those who argue that scientific history can be as subjective, as partisan, and as lacking in discrimination as any other kind of history. A century after the close of Reconstruction, we are utterly uninformed about numerous aspects of the period. Almost forty years ago Howard K. Beale, writing in the American Historical Review, called for a treatment of the Reconstruction era that would not be marred by bitter sectional feelings, personal vendettas, or racial animosities.36 In the four decades since that piece was written, there have been some historians who have heeded Beale’s call. It would, indeed, be quite remarkable if historians of today were not sensitive to some of the strictures Beale made against those who kept alive the hoary myths about Reconstruction and if scholars of today’s generation did not attempt to look at the period without the restricting influences of sectional or racial bias. And yet, since the publication of Beale’s piece, several major works have appeared that are aggressively hostile to any new view of Reconstruction.37 Nor has Beale’s call been heeded to the extent that it should have been.

If histories do indeed reflect the problems and concerns of their authors’ own times, numerous major works on Reconstruction should have appeared in recent years. After all, since the close of World War II this nation has been caught up in a reassessment of the place of Negroes in American society, and some have even called this period the “Second Reconstruction.”38 Central to the reassessment has been a continuing discussion of the right of blacks to participate in the political process, to enjoy equal protection of the laws, and to be free of discrimination in education, employment, housing, and the like. Yet among the recent writing on Reconstruction few major works seek to synthesize and to generalize over the whole range of the freedmen’s experience, to say nothing of the problem of Reconstruction as a whole. Only a limited number of monographic works deal with, for example, Reconstruction in the states, the regional experiences of freedmen, the freedmen confronting their new status, aspects of educational, religious, or institutional development, or phases of economic adjustment.

In recent years historians have focused much more on the period of slavery than on the period of freedom. Some historians have been most enthusiastic about the capacity of slaves to establish and maintain institutions while in bondage, to function effectively in an economic system as a kind of upwardly mobile group of junior partners, and to make the transition to freedom with a minimum of trauma.39 One may wonder why, at this particular juncture in the nation’s history, slavery has attracted so much interest and why, in all of the recent and current discussions of racial equality, Reconstruction has attracted so little. Not even the litigation of Brown v. The Board of Education, which touched off a full-dress discussion of one of the three Reconstruction Amendments a full year before the decision was handed down in 1954, stimulated any considerable production of Reconstruction scholarship.40 Does this pattern suggest that historians have thought that the key to understanding the place of Afro-Americans in American life is to be found in the slave experience and not in the struggles for adjustment in the early years of freedom? Or does it merely mean that historians find the study of slavery more exotic or more tragic and therefore more attractive than the later period of freedom? Whatever the reason, the result has been to leave the major thrust of the Reconstruction story not nearly far enough from where it was in 1929, when Claude Bowers published The Tragic Era.

That result is all the more unfortunate in view of what we already know and what is gradually and painfully becoming known about the period following the Civil War. With all of the exhortations by Howard Beale, Bernard Weisberger, and others about the need for more Reconstruction studies, the major works with a grand sweep and a bold interpretation have yet to be written. Recent works by Michael Perman and Leon F. Litwack, which provide a fresh view respectively of political problems in the entire South and of the emergence of the freedman throughout the South, are indications of what can and should be done in the field.41 And, even if the battle for revision is being won among the professionals writing the monographs (if not among the professionals writing the textbooks), it is important to make certain that the zeal for revision does not become a substitute for truth and accuracy and does not result in the production of works that are closer to political tracts than to histories.

Although it is not possible to speak with certainty about the extent to which the Reconstruction history written in our time reveals the urgent matters with which we are regularly concerned, we must take care not to permit those matters to influence or shape our view of an earlier period. That is what entrapped earlier generations of Reconstruction historians who used the period they studied to shape attitudes toward problems they confronted. As we look at the opportunities for new syntheses and new interpretations, we would do well to follow Thomas J. Pressly’s admonition not to seek confirmation of our views of Reconstruction in the events of our own day.42 This caveat is not to deny the possibility of a usable past, for to do so would go against our heritage and cut ourselves off from human experience.43 At the same time it proscribes the validity of reading into the past the experiences of the historian in order to shape the past as he or she wishes it to be shaped.

The desire of some historians to use the Reconstruction era to bolster their case in their own political arena or on some other ground important to their own well-being is a major reason for our not having a better general account of what actually occurred during Reconstruction. To illustrate this point, we are still without a satisfactory history of the role of the Republican Party in the South during Reconstruction. If we had such a history, we would, perhaps, modify our view of that party’s role in the postbellum South. We already know, for example, that the factional fights within the party were quite divisive. The bitter fight between two factions of Republicans in South Carolina in 1872 is merely one case in point. On that occasion the nominating convention split in two and each faction proceeded to nominate its own slate of officers. Only the absence of any opposition party assured a Republican victory in the autumn elections.44 In some instances blacks and whites competed for the party’s nomination to public office, thus indicating quite clearly the task facing a Negro Republican who aspired to public office.45 That is the task that John R. Lynch faced when he ran for Congress in 1872 and defeated the white incumbent, L. W. Pearce, who was regarded even by Lynch as “a creditable and satisfactory representative.”46 And it was not out of the question for white Republicans to work for and vote for white Democrats in order to make certain that Negro Republican candidates for office would be defeated.47 So little is known of the history of the Republican Party in the South because the presumption has generally been that Lincoln’s party was, on its very face, hostile to Southern mores generally and anxious to have Negroes embarrass white Southerners. Indeed, had historians been inclined to examine with greater care the history of the Republican Party in the South, they would have discovered even more grist for the Democratic Party mill.

Thus, studying works on Reconstruction that have been written over the last century can provide a fairly clear notion of the problems confronting the periods in which the historians lived but not always as clear a picture of Reconstruction itself. The state of historical studies and the level of sophistication in the methods of research are much too advanced for us to be content with anything less than the high level of performance found in works on other periods of United States history. There is no reason why the facts of Reconstruction should be the subject of greater dispute than those arising out of Askia Muhammad’s rule in Songhay or Cromwell’s rule in Britain. But we are still doing the spade-work; we are still writing narrowly focused monographs on the history of Reconstruction. We need to know more about education than Henry L. Swint, Horace Mann Bond, and Robert Morris have told us.48 Surely there is more to economic development than we can learn from the works by Irwin Unger, George R. Woolfolk, Robert P. Sharkey, and Carl Osthaus.49 And race, looming large in the Reconstruction era, as is usually the case in other periods of American history, is so pervasive and so critical that the matter should not be left to Herbert G. Gutman, Howard Rabinowitz, John H. and La Wanda Cox, Thomas Holt, and a few others.50

Recent scholarship on the Reconstruction era leaves the impression that we may be reaching the point, after a century of effort, where we can handle the problems inherent in writing about an internal struggle without losing ourselves in the fire and brimstone of the Civil War and its aftermath. Perhaps we have reached the point in coping with the problems about us when we no longer need to shape Reconstruction history to suit our current needs. If either or both of these considerations is true, we are fortunate, for each augurs well for the future of Reconstruction history. It would indeed be a happy day if we could view the era of Reconstruction without either attempting to use the events of that era to support some current policy or seeking analogies that are at best strained and provide little in the way of an understanding of that era or our own.

“Not since Reconstruction” is a phrase that is frequently seen and heard. Its principal purpose is to draw an analogy or a contrast. Since it usually neither defines Reconstruction nor makes clear whether it is a signpost of progress or retrogression, searching for some other way of relating that period to our own may be wise, if not necessary. In the search for the real meaning of Reconstruction, phrases like “not since Reconstruction” provide no clue to understanding the period. Worse still, they becloud the relationship between that day and this. To guard against the alluring pitfalls of such phrases and to assure ourselves and others that we are serious about the postbellum South, we would do well to cease using Reconstruction as a mirror of ourselves and begin studying it because it very much needs studying. In such a process Reconstruction will doubtless have much to teach all of us.

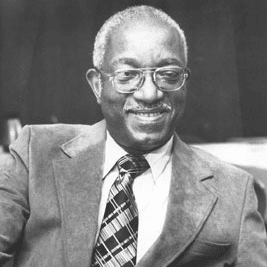

John Hope Franklin (1915–2009) accumulated a number of distinctions and awards as one of America’s most accomplished historians. His 1947 study of the African American experience, From Slavery to Freedom, remains among the most notable and widely read works in the field. Dr. Franklin earned his PhD at Harvard University in 1941 and has taught at a number of institutions, including Duke University, Howard University, and the University of Chicago. In addition to the American Historical Association, he has served as president of the American Studies Association (1967), the Southern Historical Association (1970), and the Organization of American Historians (1975). He has been a member of the Board of Trustees of Fisk University, the Chicago Public Library, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association. Dr. Franklin has served on a number of national commissions including the National Council of the Humanities, the President’s Advisory Commission on Ambassadorial Appointments, and One America: The President’s Initiative on Race (1997). He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995.

Notes

- Nehemiah Levtzion, “The Long March of Islam in the Western Sudan,” in Roland Oliver, ed., The Middle Age of African History (London, 1967), 16–17. [↩]

- Leo Africanus, The History and Description of Africa, 3 (New York, n.d.): 823–25; and Mahmoud Kati, Ta-rikh El-Fettach, ed. O. Houdas and M. Delafosse (Paris, 1913), 13–54. [↩]

- See, for example, Christopher Hill, Puritanism and Revolution: Studies in Interpretation of the English Revolution of the 17th Century (New York, 1964), esp. chap. 1; and David Underdown, Royalist Conspiracy in England (New Haven, 1960). [↩]

- Pike, The Prostrate State: South Carolina under Negro Government (New York, 1873). [↩]

- See the very favorable comments by Henry Steele Commager in the introduction to a reissue of The Prostrate State (New York, 1935). [↩]

- Durden, James Shepherd Pike. Republicanism and the American Negro, 1850–1882 (Durham, N.C., 1957), 214–19. [↩]

- Hamilton, “William Archibald Dunning,” Dictionary of American Biography, 3, pt. 1: 523. [↩]

- Dunning, Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865–1877 (New York, 1907), 116, 120, 121, 213. [↩]

- Walter L. Fleming, ed., Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial, 1865–1906, 1 (New York, 1966): 267. [↩]

- For some of the best examples of the work of Dunning’s students, see Walter L. Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (New York, 1905); and Joseph G. de Roulhac Hamilton, Reconstruction in North Carolina (New York, 1914). [↩]

- Rhodes, History of the United States, 7 (New York, 1906): 168. [↩]

- Dixon, The Leopard’s Spots. A Romance of the White Man’s Burden (New York, 1902), The Clansman. An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (New York, 1905), and The Traitor: A Story of the Rise and Fall of the Invisible Empire (New York, 1907); and Bowers, The Tragic Era: The Revolution after Lincoln (New York, 1929). [↩]

- DuBois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” Atlantic Monthly, 87 (1901): 354–65, and “Reconstruction and Its Benefits,” AHR, 15 (1909–10): 781–99. [↩]

- Lynch, The Facts of Reconstruction (Boston, 1913), Preface, 92–99 (this entire volume is reprinted in John Hope Franklin, ed., Reminiscences of an Active Life: The Autobiography of John Roy Lynch [Chicago, 1970], xxvii–xxxviii), and Some Historical Errors of James Ford Rhodes (Boston, 1922), xvii. The latter work originally appeared as two articles in the Journal of Negro History: “Some Historical Errors of James Ford Rhodes,” 2 (1917): 345–68, and “More about the Historical Errors of James Ford Rhodes,” 3 (1918): 139–57. Also see John Garraty, ed., The Barber and the Historian: The Correspondence of George A. Myers and James Ford Rhodes (Columbus, Ohio, 1956), 29–38. [↩]

- Taylor, The Negro in South Carolina during the Reconstruction (Washington, 1924), The Negro in the Reconstruction of Virginia (Washington, 1926), and The Negro in Tennessee (Washington, 1941). [↩]

- DuBois, Black Reconstruction: An Essay toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct America, 1860–1880 (New York, 1935), 713. [↩]

- Ibid., 724. [↩]

- Buck, The Road to Reunion (Boston, 1937); Bond, Negro Education in Alabama: A Study in Cotton and Steel (Washington, 1939); and Wharton, The Negro in Mississippi (Chapel Hill, 1947). [↩]

- Coulter, The South during Reconstruction (Baton Rouge, 1947), xi, 86, 336. [↩]

- W. L. Nunn, Texas under the Carpetbaggers (Austin, 1962), 19, 25n. [↩]

- Thomas A. Bailey, The American Pageant: A History of the Republic (Boston, 1961), 475–76. [↩]

- Joe Gray Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863–1877 (Baton Rouge, 1974), 49. [↩]

- Joel Williamson, After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction, 1861–1877 (Chapel Hill, 1965), 63. Also see Roberta Sue Alexander, “North Carolina Faces the Freedmen: Race Relations during Presidential Reconstruction, 1865–1867” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1974). [↩]

- For examples of such work, see Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 (New York, 1976); John W. Blassingame, Black New Orleans, 1860–1880 (Chicago, 1973); and Carl R. Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedmen’s Savings Bank (Urbana, Ill., 1976). [↩]

- Rembert Patrick, The Reconstruction of the Nation (New York, 1967); Kenneth M. Stampp, The Era of Reconstruction, 1867–1877 (New York, 1965); and John Hope Franklin, Reconstruction after the Civil War (Chicago, 1961). [↩]

- See, for example, A. A. Taylor, “Historians of the Reconstruction,” Journal of Negro History, 23 (1938): 16–34; Francis H. Simkins, “New Viewpoints of Southern Reconstruction,” Journal of Southern History, 5 (1939): 49–61; Howard K. Beale, “On Rewriting Reconstruction History,” AHR, 45 (1939–40): 807–27; T. Harry Williams, “An Analysis of Some Reconstruction Attitudes,” Journal of Southern History, 12 (1946): 469–86; Bernard A. Weisberger, “The Dark and Bloody Ground of Reconstruction Historiography,” ibid., 25 (1959): 427–47; Vernon L. Wharton, “Reconstruction,” in Arthur S. Link and Rembert W. Patrick, eds., Writing Southern History: Essays in Historiography in Honor of Fletcher M Green (Baton Rouge, 1965), 295–315; and John Hope Franklin, “Reconstruction and the Negro,” in Harold M. Hyman, ed., New Frontiers of the American Reconstruction (Urbana, Ill., 1966), 59–76. [↩]

- For a discussion of the impact of the scientific study of history on research and writing, see W. Stull Holt, “The Idea of Scientific History in America,” in his Historical Scholarship in the United States and Other Essays (Seattle, 1967), 15–28. [↩]

- Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama, 523. Fleming knew better, for in another place—deep in a footnote—he asserted that Rapier was from Lauderdale, “educated in Canada”; ibid., 519n. [↩]

- Loren Schweninger, James T. Rapier and Reconstruction (Chicago, 1978), xvii, 15. [↩]

- Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama, 12. For an account of Yancey and other white Southerners in the North to secure an education, see John Hope Franklin, A Southern Odyssey: Travelers in the Antebellum North (Baton Rouge, 1976), 45–80. [↩]

- Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama, viii–ix; and Du Bose, Alabama’s Tragic Decade, 1865–1874 (Birmingham, Ala., 1940). Du Bose’s work is a collection of his newspaper articles published in 1912. [↩]

- Du Bose, The Life and Times of William Lowndes Yancey (Birmingham, Ala., 1892), 407–22. [↩]

- Thomas McAdory Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, 4 vols. (Chicago, 1921), 2: 845–46, 4: 1335, 3: 278. For a discussion of the problem of defining carpetbaggers in Alabama, see Bond, Negro Education in Alabama, 65. [↩]

- Hamilton, Reconstruction in North Carolina, 663. [↩]

- Ibid., 666–67. [↩]

- Beale, “On Rewriting Reconstruction History,” 807–27. [↩]

- See, for example, Coulter, The South during Reconstruction; and Bailey, The American Pageant, chap. 24. [↩]

- See C. Vann Woodward, “The Political Legacy of Reconstruction,” in his The Burden of Southern History (New York, 1961), 107. [↩]

- For some of the works that deal with these themes, see John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community. Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York, 1972); Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York, 1974); Robert William Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman, Time on the Cross. The Economics of American Negro Slavery, 2 vols. (Boston, 1974); Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom; and David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Ithaca, N.Y., 1966), and The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1975). [↩]

- A few who were associated with counsel for the plaintiffs have published some of their work. See, for example, Alfred H. Kelly, “The Congressional Controversy over School Segregation, 1867–1875,” AHR, 64 (1958–59): 537–63; and John Hope Franklin, “Jim Crow Goes to School: The Genesis of Legal Segregation in Southern Schools,” South Atlantic Quarterly, 58 (1959): 225–35. [↩]

- Perman, Reunion without Compromise: The South and Reconstruction, 1865–1868 (Cambridge, 1973); and Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York, 1979). [↩]

- Pressly, “Racial Attitudes, Scholarship, and Reconstruction: A Review Essay,” Journal of Southern History, 32 (1966): 90. [↩]

- J. R. Pole, “The American Past: Is It Still Usable?” Journal of American Studies, 1 (1967): 70–72. [↩]

- Edward F. Sweat, “Francis L. Cardozo—Profile in Reconstruction Politics,” Journal of Negro History, 46 (1961): 217–32. For examples of other intraparty conflicts, see Robert H. Woody, “Jonathan Jasper Wright, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1870–77,” ibid., 18 (1933): 114–31; and Schweninger, James T Rapier and Reconstruction, 75, 144. [↩]

- Schweninger, James T. Rapier and Reconstruction, 114. [↩]

- Franklin, Reminiscences of an Active Life. The Autobiography of John Roy Lynch, 101–02. [↩]

- Thomas B. Alexander, Political Reconstruction in Tennessee (Nashville, 1950), 204–05, 240–41; and Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863–1877, 214. [↩]

- Swint, Northern Teacher in the South (Nashville, 1941); Bond, Negro Education in Alabama; and Morris, “Reading, ‘Ritin’, arid Reconstruction” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1976). [↩]

- Unger, The Greenback Era: A Social and Political History of American Finance, 1865–1879 (Princeton, 1965); Woolfolk, The Northern Merchants and Reconstruction, 1865–1880 (New York, 1958); Sharkey, Money, Class, and Party: An Economic Study of Civil War and Reconstruction (Baltimore, 1959); and Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedmen’s Savings Bank. [↩]

- Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom; Rabinowitz, Race Relations in the Urban South (New York, 1978); Cox and Cox, Politics, Principles, and Prejudice, 1865–1866: Dilemma of Reconstruction America (New York, 1963); and Holt, Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction (Urbana, Ill., 1977). [↩]