Annual address of the president of the American Historical Association, delivered on December 28, 1984. Published in American Historical Review 90, no. 1, (Feb., 1985), pp. 1-17.

The American Historical Association, 1884–1984: Retrospect and Prospect

The American Historical Association is now slightly more than one hundred years old. Centennials do not happen very often, and tonight we can, with justifiable pride, review the past century and note the central role that our organization has played in the development of a large and many-faceted historical enterprise in the United States over the past century. And we can, even more appropriately, take a candid look at our association as it stands today and consider its problems, challenges, and opportunities.

It seems safe to say that some kind of national American historical association was inevitable during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The original proposal for the association came from Daniel Coit Gilman, organizer and president of The Johns Hopkins University, the first modern research-oriented university in the United States.1 But Herbert Baxter Adams, an associate professor of history at the Johns Hopkins (whom Woodrow Wilson later described as “a great Captain of Industry,—a captain in the field of systematic and organized scholarship”),2 took the lead in planning the first meeting. Undoubtedly Adams drafted the call for the formation of the association at Saratoga Springs, New York, on September 9, 1884, a summons that was widely circulated.3 Before that date, Adams made certain that most of the leading historians in the country would attend, arranged the first program, and drew up the first slate of officers.4

On the morning of September 9, 1884, “a private gathering of the friends of the Historical Association,” as Adams called it, met in a small parlor of the United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs. The group discussed whether the new organization should remain a section of the American Social Science Association, founded in 1865, which included historians in its membership, or become an independent body. The answer was foreordained. Most of those present were full-time historians or economists; indeed, the group included leaders of those two fields, as well as political scientists. As the chairman of the group, Justin Winsor, librarian of Harvard College and editor of the then-new Narrative and Critical History of America series, argued: “We have come, gentlemen, to organize a new society, and fill a new field…. Our proposed name, though American by title, is not intended to confine our observations to this continent. We are to be simply American students devoting ourselves to historical subjects, without limitation in time or place…. We are drawn together because we believe there is a new spirit of research abroad,—a spirit which emulates the laboratory work of the naturalists, using that word in its broadest sense. That spirit requires for its sustenance mutual recognition and suggestion among its devotees.”5

There followed a spirited discussion of a resolution to test the sentiment of the group, and only John Eaton, president of the ASSA and also United States Commissioner of Education, opposed the motion for independence. Later that same day, September 9, forty persons met in Putnam Hall and heard an address by the AHA’s first president, Andrew D. White, a German-trained former professor of history at the University of Michigan and, since 1868, president of Cornell University. The association met in business session on the morning of September 10 and adopted a constitution presented by Charles Kendall Adams of the University of Michigan. Surely one of the shortest ever drafted, the constitution filled slightly more than a single printed page. The document said simply that the “name of this Society shall be the American Historical Association” and that “its object shall be the promotion of historical studies.” The last two articles created officers and an Executive Council and provided a method of amendment. Any person approved by the Executive Council could become a member upon payment of annual dues of three dollars.6

If we can now see that the time was ripe for the organization of a national professional historical association, that fact was not self-evident in 1884. The universities and colleges in the entire United States appear to have had, as John Franklin Jameson later noted, only fifteen full-time professors of history and five full-time assistant professors. The number of graduate students in history was probably not more than thirty.7 Even so, the association began its second year with 220 members. They included a former president of the United States, Rutherford B. Hayes, who was one of the founders, and a future president of the United States and of the AHA (1924), who signed himself simply as “Woodrow Wilson, Esq., Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md.” In 1885, three of the members were women.

From this small beginning, the growth of the association during its first twenty-five years was phenomenal.8 By 1909 the AHA had a membership of about twenty-five hundred and was the largest and most active historical organization in the world. This growth occurred even while the association, which had originally included scholars in most branches of the social sciences, began to experience fragmentation owing to the professionalization of sister disciplines. The American Economic Association broke away in 1885, although it held joint meetings with the AHA in that year, in 1886, and in 1909. Then, after the founding of the American Political Science Association in 1903 and the American Sociological Society in 1905, each major social science discipline possessed its own national organization.

Constitutionally, the AHA underwent little change during the first ninety years of its existence. The original constitution entrusted governance to an Executive Council whose voting members included not only the elected members but also all past presidents. For example, in 1915, twenty-eight members of the Executive Council included twenty-one former presidents. In order to head off a revolt (which proved to be abortive) led by Frederic Bancroft (former librarian of the Department of State), Dunbar Rowland, and John H. Latané,9 the leaders of the Executive Council in 1915 put through an amendment, which decreed that presidents on leaving office might sit on the Council for life but could vote for only three years—”and no longer.” An amendment adopted in 1969 permitted former presidents, who still held membership on the Council for life, to vote for only one year. The constitution adopted in 1974, under which we operate today, attempted to rationalize the work of what was now called simply the Council by reducing its elected membership from twelve to nine and by creating Research, Teaching, and Professional divisions, each headed by vice-presidents. The constitution of 1974 also excluded all former presidents from membership on the Council, with the exception of the current past president, who serves for one year following his or her incumbency.10

The American Historical Association has undergone many important structural changes since Herbert Baxter Adams conducted its business from his hip pocket. During its first decade, the AHA catered to nonacademic historians and public figures, including college and university presidents. Such a secretariat as it possessed was Adams’s office in Baltimore. In 1889, A. Howard Clark of the National Museum, now a forgotten figure, was made assistant secretary and curator, a post he held until 1908. Being on the scene, he arranged for publication of the annual reports. Adams’s death in 1901 compelled a reconsideration of the organization. Charles Homer Haskins was made secretary of the Executive Council and held that post until 1914. Clark was succeeded as secretary by Waldo Gifford Leland, who served until 1919. John Spencer Bassett and Dexter Perkins, neither of them residents of Washington, succeeded as secretary in 1919 and 1928.

Actually, much of the continuity and organization was provided by Jameson, who edited the American Historical Review for most of the years from 1895 to 1928. When Jameson moved to Washington in 1905 to head the Bureau of Historical Research of the Carnegie Institution, he used the facilities of the institution as his editorial office. The AHA did not need new housing until 1928, when Jameson gave up the editorship of the Review and became chief of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

During the years 1928 to 1941 the AHA realized the need to concentrate its activities in Washington and obtain an executive secretary—full-time if possible, part-time if necessary. Conyers Read was the first in 1933, but he remained in Philadelphia and served only part-time. A constitutional amendment abolished the office of secretary, still held by Perkins. In 1941 Guy Stanton Ford became the first full-time executive secretary of the association and editor of the Review, with offices in what was then called the Library of Congress Annex. Concentration in Washington was achieved, and a building for the headquarters of the association was purchased in 1956. The combined editorial and executive functions became unworkable, however, because of the increase in the activities of the secretariat in the late 1950s. With Boyd Shafer’s retirement in 1963–64, the inevitable split occurred. Succeeding executive secretaries and executive directors (the title changed under the constitution of 1974) were W. Stull Holt, 1963–64, who briefly recombined the offices of executive secretary and managing editor of the AHR; Louis B. Wright, 1964–65; Paul L. Ward, 1965–74; Mack Thompson, 1974–81; and Samuel R. Gammon, since 1981. The successors to Shafer as managing editor of the American Historical Review were Holt, 1963–64; Henry R. Winkler, 1964–68; and R. K. Webb, 1968–75. John Duffy, Robert F. Byrnes, and Robert E. Quirk were interim editors during the period when the Review was moved to Indiana University. Otto Pflanze assumed the editorship there beginning with the issue of April 1977.

Let us now turn back to the character, ideals, and activities of the founders and members of the American Historical Association since its early years. The first thing to be said about the American Historical Association is that it has always been nondiscriminatory in its acceptance of members. The constitution of 1884 said simply, “Any person approved by the Executive Council may become a member by paying three dollars.” Approval was always pro forma, if, indeed, it was actually ever given. And, to my knowledge, no person who has applied for membership in the AHA has been turned down on grounds of race, gender, religion, national origin, or political views.

Nonetheless, the association cannot boast of ever having been much in advance of the practices and customs of American society. Technically, a black woman could have been elected president. But the provisions of constitutions often do not conform to the realities of life. It is true that W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, the first black Ph.D. in the United States, was on the programs at AHA annual meetings in 1891 and 1909. In the annual reports and American Historical Review, the association also published his papers—the second of which was a major revisionist manifesto on Reconstruction11—and a large number of papers on blacks in slavery and freedom. Yet few blacks were members of or active in the association until the 1960s, no black person was a member of the Council until 1959, and no black was president of the association until 1979.

Although the AHA had Jewish members from the beginning of the association, their numbers, until the 1950s, were infinitesimal compared to the total membership. In some extenuation, this was true because the AHA increasingly drew its members from the ranks of professional historians, and the unwritten but nearly ironclad rule against the employment of Jews in all except a few colleges and universities made it foolhardy for many Jewish undergraduates to contemplate a career in the historical profession. Anti-Semitic walls in the United States crumbled, however, with astonishing speed in the 1940s and 1950s, and Jews then began to enter the historical profession in large numbers and to play an increasingly active role as members and officers of the AHA. The first Jewish president served in 1953.

Women, too, have been members of the AHA since 1885. Indeed, a resolution adopted by the Executive Council at its first meeting proclaimed that, “in the opinion of the Council, there is nothing in the Constitution of the American Historical Association to prevent the admission of women into the Association upon the same qualifications as those required of men.”12 Among 2,519 individual members in 1920, 483 women can be positively identified, or 19 percent of the whole. In 1950, 792 (about 15 percent) of 5,300 members were women. The AHA has kept membership lists and statistics on computer tapes since 1973. In that year, the association had some 16,000 dues-paying members, of whom 2,352 (about 15 percent) were women. In 1977, there were 10,620 male members and 2,774 female members (21 percent). In 1983, male membership stood at 8,691, female at 2,563 (23 percent).

Membership lists before 1960 reveal a number of distinguished female members of the AHA. Yet the records also reveal that women were given short shrift in positions of governance and leadership in the association for the greater part of that period. For example, out of a total of ninety-six members of the Executive Council before 1933, five were women, a situation that changed little during the next forty years. Only ten women served on the Executive Council between 1934 and 1971; during the same period, women had scattered representation on various committees, in a ratio of about one to nine. And the AHA has had only one woman president, who served in 1942.

Like all other professional organizations, the AHA could not withstand the winds of social change that have been gusting across the United States since the mid-1960s. For reasons at once too obvious and too complicated to discuss here, the barriers against broad and extensive participation and leadership by women in the AHA collapsed all at once—in 1973. In that year, three women sat on the Executive Council and on the nominating committee. And I think it accurate to say that since 1973 every nominating committee and every committee on committees has been cognizant of the great resources of scholarship and leadership that our female members bring to the association.

Growing diversity in the membership and leadership of the AHA since the 1950s has been the single most important event in the history of the association. It is a good thing that our founders declared that anyone could become a member of the AHA. It is a much better thing that the association, in approving the report of the so-called Hackney Commission in 1974, said that it welcomed and would honor, encourage, and defend as best it could all members without regard to gender, race, politics, religion, or lifestyle.13

Publication of scholarly work has always been vital to the promotion of historical studies, and the American Historical Association since its founding has played a key, if not a dominant, role in this activity. The AHA’s first reports, Papers of the American Historical Association, were published from 1885 to 1891 by G. P. Putnam’s Sons of New York. Congress granted the association a federal charter in 1889 and said that the Smithsonian Institution might publish the annual reports. The first such publication was the annual report for 1889, published in 1890. And with publication and distribution free of cost, the annual reports almost immediately waxed huge in size. They included not only the reports of the annual meetings and the minutes of the Executive Council and standing and special committees but also, taken altogether, thousands of articles, monographs, and editions of letters and other documents. Publication on this scale continued until the late 1910s and then, after the mid-1920s, intermittently, included editions of diaries, diplomatic documents, and the like.14 The Annual Report for 1945 was the last to contain edited collections, because the period 1945–50 marked a turning point in historical editing in the United States: the introduction of new scholarly standards and a widespread assumption that large, important scholarly editions had to be produced by groups of scholars collaborating on projects underwritten by foundations, corporations, and the federal government.

The spread of such series as the Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science (founded in 1882), the proliferation of specialized historical journals, such as the Mississippi Valley Historical Review (since 1964 the Journal of American History), and, probably most important, the rapid growth in the number of university presses in the 1920s and afterwards, all help account for the demise of the annual reports as outlets for monographs. Even so, the AHA did not abandon the field. By the late 1920s, it had the resources of the Albert J. Beveridge Fund, the Littleton-Griswold Fund, and what was called the revolving fund of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. With these resources it was able to sponsor and subsidize publication of many monographs in American history in general and, in the case of the Littleton-Griswold Fund, of early American legal records.

The founding of the American Historical Review by J. Franklin Jameson and others in 1895 brought into being another outlet for articles and, perhaps more important, a journal devoted to the critical review of historical works. The AHR was originally an independent journal, which was marketed commercially by the Macmillan Company; the editors, who legally owned the Review, gladly turned over title to and financial responsibilities for it to the association in 1915.15 Along with his board of editors, Jameson made the AHR a worthy rival of the Historische Zeitschrift, founded in 1876, and the Revue historique, founded in 1884. Under a series of distinguished editors, the American Historical Review has flourished and continues to be one of the few journals in the world that attempts to cover all fields of history. Since its founding, the AHR has always been the flagship of the association. May it ever continue to be thus!

Looking back over the works published in the annual reports and the American Historical Review, one is impressed most notably by their range and diversity. Since many early leaders of the AHA were trained by German professors who stressed the universality of history, and since this tradition was also strong in historical training in the United States, it was inevitable that the American Historical Association should have begun as an organization dedicated to the promotion of all historical study. It has been and continues to be the one historical organization in the United States that brings historians in all fields and specialties into discussion, communication, and fellowship. Therefore, it has been and continues to be the one and only organization that can speak for the entire historical profession in this country. Catholicity of interest is one of our noblest traditions. We must maintain it with all our strength in the century that lies ahead.

The thing that struck me most forcibly as I looked through the annual reports for the first twenty-five years was, first, the emphasis placed by the leaders of our profession on work in social, cultural, and economic history and on the experiences of so-called ordinary folk and, second, the degree to which young historians heeded the call of their mentors to write this kind of history. Andrew D. White’s first presidential address, “On Studies in General History and the History of Civilization,” was a clarion call for cultural history on a grand scale.16 In his presidential address of 1900, entitled “The New History,” Edward Eggleston vented his scorn for Edward A. Freeman’s famous aphorism, as follows: “Never was a falser thing said than that history is dead politics and politics living history. Some things are false and some things are perniciously false. This is one of the latter kind.”17 James Harvey Robinson had been speaking and writing about social and cultural history and the importance of the new social sciences to the study of history for years before he published his famous manifesto, The New History, in 1912. As John Higham has pointed out, the “new” history was not so new in 1912.18

As for methodology and styles and kinds of history, it can be said to their credit that the councils and committees of the AHA have always maintained an open mind on such matters without ever being coercive about them. By joining the American Council of Learned Societies upon its founding in 1919, the association affirmed that history is one of the humane disciplines; by joining the Social Science Research Council in 1925, after two years of hesitation, the association affirmed that history is also one of the social sciences. The association, of course, has had enthusiasts for various methodologies and interpretations but few sectarians, certainly not enough of them to divide the leadership and membership into warring camps. Even on the rare occasions when AHA committees have composed reports on methodology and historiography, they have written in good temper and with due respect for what might be called the great traditions of modern historical scholarship.19

The compilation of bibliographies consumed much of the energy of committees and members of the AHA during the first thirty-odd years of its existence. If our forebears seem to have had a passion for bibliographies, we must remember that they were in fact laying the foundations for historical research in this country. This work was formalized by the Executive Council’s appointment of a Committee on Bibliography in 1898; it remained a standing committee of the Council until 1919. The most notable series sponsored by the association has been the publication in 1902–03, 1906–40, and 1948–61, of Writings on American History, compiled from 1906 through 1940 by Grace Gardner Griffin—that devoted servant of historians.20 The crowning bibliographical achievement of the AHA was its Guide to Historical Literature, originally published in 1931 and drastically revised in 1961, when it was certainly the best single-volume bibliography of historical writing in all epochs and fields.

Limitations of time prevent a proper recognition of the work of the councils and committees of the AHA in what is called public history—in organizing local and state historical societies, cataloguing their resources, upgrading their standards, and encouraging the establishment of state historical commissions or state departments of archives and history. The Executive Council created a Public Archives Commission in 1899, and that body began in 1909 to hold an annual conference of archivists. In 1904 the Executive Council also created a General Committee to hold annual conferences of persons active in local and state societies. Close cooperation between the AHA and local and state societies and archives continued until the establishment of the Society of American Archivists in 1936 and the American Association for State and Local History in 1940, which rendered the AHA’s activities in these fields redundant.21

As historical scholars who insisted that work in original sources, particularly manuscripts, was the sine qua non of research, the first members of the AHA were appalled by the lack of guides to historical manuscripts in the United States. The business meeting of the association’s second annual meeting instructed the Council “to represent to our government the advantages and the advisability of cataloguing all documents relating to the history of the United States down to the year 1800 existing in the official and private archives of Europe, and of copying and printing the more important of them.”22 After the federal incorporation of the association in 1889, there were high hopes for the establishment of a federal historical manuscripts commission modeled on the British Historical Manuscripts Commission. In a paper entitled “The Expenditures of Foreign Governments in Behalf of History,”23 read to the annual meeting in 1891, Jameson eloquently pleaded that the United States at least should match what many small European states were already doing in the publication of records. But Congress turned a deaf ear to an AHA memorial in 1894–95, and the association, in the latter year, established its own Historical Manuscripts Commission, headed by Jameson.24

The Historical Manuscripts Commission existed as a standing committee of the AHA through 1935, but, to all intents and purposes, it had ceased to function after 1929. Meanwhile, however, it had published in the annual reports not only numerous guides and inventories to manuscripts in public archives and private hands but also many edited collections of letters, diaries, journals, and the like. The publication of the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections by the Library of Congress and two private publishers, beginning in 1962 and continuing until the present, in twenty-three large volumes, including four separate index volumes, has made further activity by the AHA in this field unnecessary.

Professional historians in the AHA during its early years were particularly distressed by the almost utter neglect by the government of the United States of its own records. Those records, if kept at all, were, with a few exceptions, arranged and administered by amateurs, were scattered among various departments of the government, and were often stored in buildings that were not fireproof. Jameson issued the first strong call for the establishment of a central national archives in 1890. “Except Switzerland, whose case is peculiar,. Jameson said, … I have found no instance of a civilized European country, not even Bavaria, Württemberg, or Baden, which does not spend more absolutely upon its archives than we do.”25

If any single institution can be called a monument to one person, then the National Archives is surely a monument to John Franklin Jameson. To be sure, the AHA Executive Council, in 1901, sent a memorial to the two houses of Congress that urged the building of a “hall of records.”26 More important, in 1908 the Executive Council appointed a committee to promote the construction of a national archives building to be staffed by trained archivists and scholars. The association petitioned Congress again to this effect in 1927 But it was Jameson who kept the pressure on the councils of the AHA and on Congresses and presidents of the United States all through the 1910s and 1920s, until success came with a congressional appropriation in 1926. Ground was broken in 1931, and the present National Archives building was opened for use in 1935.28

The act of 1934 that created the National Archives also established the National Archives Council on which neither the AHA nor any other professional organization was represented. The Executive Council of the AHA, however, did in effect dictate in 1934 the choice of the first Archivist of the United States—Robert Digges Wimberly Connor, the first secretary of the North Carolina Historical Commission and a professor of history at the University of North Carolina. Another provision of the National Archives Act called for creation of the National Historical Publications Commission, two members of which were to be appointed by the AHA. Although the commission was appointed, Congress refused to appropriate any funds for its work, “and the commission lapsed into inactivity.”29 There is no time to review the splendid work of the NHPC, which was revived by President Truman in 1950, was later given substantial appropriations, and was enlarged and renamed the National Historical Publications and Records Commission in 1974.30 We can only note here that the existence and prodigious work of this agency in promoting and subsidizing the publication of many basic records of American history represented the fruition of the hopes and dreams of Jameson and other founders of the American Historical Association.

This brings us back to the tenuous but usually friendly relationship between the United States government and the American Historical Association. The original act of incorporation of 1889, which has since been amended only slightly, is a very simple document that names certain persons and their successors as “a body corporate and politic, by the name of the American Historical Association, for the promotion of historical studies, the collection and preservation of manuscripts, and for kindred purposes in the interest of American history and of history in America.” The association was to have its principal office in Washington and report annually to the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who in turn would communicate such reports to Congress as he saw fit. As I have said, publication of the annual reports was a boon to the AHA and a major cause of its growth. But aside from this indirect subsidy, the AHA to my knowledge has never received a dollar appropriated directly by Congress. Nor has it ever applied for or wanted any such appropriations.

The AHA has preferred to act only in an advisory and consultative capacity with various governmental agencies, and even here the initiative for such a relationship has come from these agencies. In recent decades the AHA, in addition to its representation on the NHPRC, has had representatives on advisory councils to the National Archives and Records Service and the Office of the Historian of the State Department. Their work, much of it of a watchdog and supportive nature, has recently been well reviewed31 and only needs to be noted and applauded here.

The professionalization of the discipline of history occurred at the same time that secondary schools were beginning to proliferate in the United States, and the American Historical Association played a determinative role in securing an important place for history in high school curricula and in the training of history teachers in secondary schools. The basic work32 was done by a Committee of Ten, appointed by the National Education Association in 1892. This committee—the first of four influential committees designated by their membership number—was dominated by members of the AHA.33 In 1896 the association itself appointed the Committee of Seven “to consider the subject of history in the secondary schools and to draw up a scheme of college entrance requirements.”34 In 1899 this committee, whose chairperson was Andrew C. McLaughlin of the University of Michigan, recommended a four-year historical curriculum for high schools, consisting of ancient history to A.D. 800, medieval and modern European history, English history, and American history and government, or variations of this program.35

A Committee of Five, appointed by the Executive Council of the AHA in 1907 at the request of the Headmasters’ Association, with McLaughlin as chairperson, reported in 1911 that historical courses and teaching methods had been instituted and changed “from one side of the continent to the other” in response to the report of the Committee of Seven. There had, however, recently been much demand for more emphasis on modern history. The Committee of Five, saying that “the desire of teachers to emphasize modern history” had a strong appeal to its members, proposed a four-year program of historical study in high schools that included a full-year course in modern European history and English history since 1760.36 Meanwhile, the Committee of Eight of the AHA, headed by James Alton James of Northwestern University, had produced a report that recommended a program of historical courses in grammar schools.37

Minor curricular changes were undertaken in response to new developments in historiography and the rise of the social sciences. In 1916 a Committee on the Social Studies of the NEA and in 1934 a Commission on the Social Studies of the AHA called for greater room in secondary school curricula for the social sciences.38 The AHA commission, however, was vague as to what the social sciences were and what high school teachers should do with them. Meanwhile, the AHA, alone among the organizations that professed to represent the social sciences, had maintained a close relationship with the National Council for the Social Studies, formed in 1921.39 Whether the nonrecommendations of the AHA’s Commission on the Social Studies had any effect is extremely doubtful,40 because traditional history continued to enjoy a central place in high school curricula until the 1960s. In any event, the commission was the last AHA committee to address itself in an extensive way to the role history should play in the education of students in secondary schools.

The AHA used other means to maintain close contact with history teachers in secondary schools. The Council collaborated with a private publisher in 1912 to revive the moribund History Teacher’s Magazine, which said, in its first issue after its rebirth, that it was “edited under the supervision of a committee of the American Historical Association.” The name of the magazine was changed to Historical Outlook in October 1918, when it was advertised as “an organ” of the AHA. The National Council for the Social Studies became a cosponsor in 1923. Historical Outlook became the Social Studies in 1934; three years later, control and direction reverted to the publisher, and all connection between the magazine and the AHA ceased.

In the same month that the Social Studies reverted entirely to private control, the AHA and the NCSS launched a new journal for teachers—Social Education, “published for the American Historical Association and the National Council for the Social Sciences” by the American Book Company. The NCSS took over publication of Social Education in 1941 but still collaborated with the AHA in editorial matters through a joint executive board. In 1955, Social Education became the “official journal” of the NCSS, “in collaboration” with the AHA. Since January 1969,Social Education, still the official journal of the NCSS, has not mentioned the American Historical Association on its masthead.

While professional historians and the AHA practiced a policy of benign neglect toward secondary schools in the early 1960s, the social scientists—anthropologists, economists, and sociologists—moved into the vacuum and began to reorganize high school curricula. As Hazel Whitman Hertzberg has observed, the social scientists were essentially ahistorical, and the so-called reformers tolerated history only insofar as it could be justified as a social science. Then came the upheavals of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The emphasis was now on “relevance” and “self-realization,” “inquiry” and “discovery.” As Hertzberg has said: “The new emphasis was both ahistorical and antihistorical. The past was relevant only when it dealt with matters of burning social or personal concern.”41 Richard S. Kirkendall, speaking in 1975 for a committee of the Organization of American Historians, said, “History is in crisis.”42 It still is, although there are now signs that thoughtful people throughout the country deeply regret the assault on history and the other liberal arts in the secondary schools.

For this turn in opinion, we have to give most of the credit to other publicists and can claim little credit for ourselves.43 To be sure, the AHA’s Service Center for Teachers of History did sponsor, between 1958 and 1965, the writing and publication of seventy-four pamphlets on various aspects and fields of history. This excellent series was (and is) a great success, but in all candor it has to be said that most of the essays were written for graduate students and college teachers, not secondary school teachers. And the Teaching Division of the Council has, among other things, from time to time sponsored regional conferences on the teaching of history in which high school teachers have participated.44 But the reports of the vice-presidents of the Teaching Division reveal a constant sense of frustration, a feeling almost of despair, because members of that division have wanted to do many things for which there has been no money.45

These, then, have been some of the achievements and failures of the American Historical Association during its first hundred years. And what of the future, now that we begin the second century of our life? I am quite sure that the American Historical Association will be celebrating its bicentennial one hundred years from now, but, since I am not endowed with the gift of prophecy, I will confine my observations about the future to some activities that I think might well engage our energies in the years immediately ahead.

To begin with, we should always remember that, if we do not stand firmly behind the cause of history and the unfettered freedom of historical inquiry, no one else will do so. A good case in point is what happened to the National Archives when it lost its independence by being under the control of the Federal Records Administration within the new General Services Administration, founded to be the housekeeping agency of the government. The AHA and the Society of American Archivists were utterly indifferent, and the deed was done in the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949.46 A joint Committee on the Status of the National Archives, with representatives from the AHA, OAH, and SAA, strongly urged in 1968 that the independence of the National Archives be restored.47 But the organizations whose deepest interests were at stake did not follow through, and nothing happened.

It has been a far different story since the founding, at the initiative of the AHA, in 1975–76 of the National Coordinating Committee for the Promotion of History. The NCC, under the energetic directorship of Page Putnam Miller, now represents thirty-four historical associations. It has defended our interests on a number of fronts—for example, in protecting the Freedom of Information Act, in leading the fight against the National Security Agency Directive Number 84, and in protecting the funding of the NHPRC and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

To Dr. Miller and the NCC, moreover, must go much of the credit for the achievement of one of the centennial goals of the AHA—the passage of S.905, which reestablished the independence of the National Archives. Many historians and archivists worked hard during 1982–84 for the success of this measure, and we had strong bipartisan support in both houses of Congress. We are particularly grateful to Senators Mark O. Hatfield, Thomas F. Eagleton, and Charles McC. Mathias, Jr., and Representative Jack B. Brooks for seeing the bill through to adoption and to President Reagan for signing it on October 19, 1984. For this epochal victory we can felicitate ourselves and congratulate in particular Dr. Miller. Passage of S.905 ought also to be a reminder of what we can accomplish when we work together with unity and energy. I am also reminded here that, although support for the NCC has increased substantially during the past two years, it is still too small.

Another thing that should engage our attention is the problem of affiliation. At present, some seventy-nine historical societies, with a total membership of almost one hundred thousand persons, are affiliated with the American Historical Association. What troubles me is that no one seems to know what “affiliation” means, aside from the opportunity given to affiliates to hold regular sessions at our annual meetings, although probably not more than 10 percent of their members are also members of the AHA. Is it not possible for the AHA to say that affiliation carries responsibilities as well as privileges? I have asked the Council to review the question of affiliation and to see what might be done to make it meaningful and mutually beneficial, and the Professional Division now has this matter under study.

A task of far greater moment and urgency is the recovery of a crucial role for the AHA in the determination of the curricula of our secondary schools. Let us return to the field that we so unthinkingly abandoned. Let us speak, both as citizens and as professional historians, in the deep conviction that no person can live a full and rich life without intimate knowledge of his or her past. If we do not know where we came from, we cannot know who we are. And if we do not know who we are, then we flounder in ignorance, not knowing where we are going. But there is no need to preach to the converted on this subject. We have talked enough; let us act. In fact, we have under way several initiatives that the Council hopes and believes will bring the AHA back into the mainstream of the teaching of history in our secondary schools.

First, the Teaching Division is now planning a new pamphlet series to be addressed explicitly to the needs of high school teachers. These pamphlets, which will cover United States and world history, will attempt to provide high school teachers with up-to-date surveys of the periods and subjects covered, will comment on new interpretations, and will point out where emphases should be placed and what the current controversies are about. The pamphlets will also include titles of a few books recommended for further reading and perhaps sample lesson plans.

Second, the Council has voted unanimously to authorize the president to appoint a blue-ribbon commission—composed of historians, leaders in secondary school teaching, administration, and governance, and others—to survey, as did the Committee of Seven, the current situation regarding history in our high schools and proper standards for the training of high school history teachers. Numerous states are at this very moment in the process of trying to restore history as an integral part of what is called a basic core discipline. And the leaders in these same states are crying out for help from professional historians. The report of the blue-ribbon commission will come at a propitious time, perhaps at a turning point in the history of American secondary education. But we mean above all to follow through in concerted action in every state. To this end, we will have the support of the Teaching Division of the AHA, the NCC, and the Committee on Schools and Colleges of the OAH.

I had hoped to announce the appointment of this commission tonight and am disappointed that I cannot do so. But no matter. Plans are now well under way to raise the money necessary for the work of the commission and its staff. And we are determined to emulate our forebears in seeing to it that our children and grandchildren do not grow up in ignorance of their civilization’s and their country’s past.

These are some of the problems and tasks that lie immediately before us. Meanwhile, as we face the next hundred years, let us, with the same vigor and dedication of our founders, resolve, with strong and active faith in our high calling and acknowledgment of our solemn responsibility, to continue to promote the study of history in the United States.

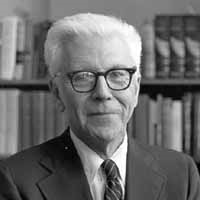

Arthur S. Link (August 8, 1920–March 26, 1998) was recognized as the world’s preeminent scholar on Woodrow Wilson as editor of The Papers of Woodrow Wilson and author of a five volume biography of Wilson. Link received his PhD from the University of North Carolina in 1941, and taught at Princeton University from 1945 to his death.

Notes

I take this opportunity to thank Samuel R. Gammon, Eileen Gaylard, David W. Hirst, Manfred Boerneke, William A. Link, and, particularly, Richard W. Leopold for invaluable help while I was writing this paper.

- Thomas L. Haskell, The Emergence of Professional Social Science: The American Social Science Association and the Nineteenth-Century Crisis of Authority (Urbana, Ill., 1977), 168–71. For corroboration of Gilman’s authorship of the idea, see J. Franklin Jameson, “The American Historical Association, 1884–1909,” AHR, 15 (1909–10): 4. [↩]

- Wilson to Richard T. Ely, January 30, 1902, in Arthur S. Link et al., eds., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 48 vols. to date (Princeton, N.J., 1966–), 12: 264. [↩]

- Papers of the American Historical Association [hereafter, AHA Papers], 1 (New York, 1886): 5. [↩]

- Adams to D. C. Gilman, August 8, 1884, in W. Stull Holt, ed., Historical Scholarship in the United States, 1876–1901: As Revealed in the Correspondence of Herbert B. Adams (Baltimore, 1938), 71–72. [↩]

- AHA Papers, 1: 11. [↩]

- Ibid., 20–21. [↩]

- Jameson, “The American Historical Association, 1884–1909,” 2–3. [↩]

- The growth was due in large part to an increase in the number of colleges and universities, an increase in the enrollment in institutions of higher learning from 116,000 in 1880 to 355,000 in 1910, and, above all, to the important place that history occupied in college curricula. In addition, there was a steady growth in professional graduate study in history in the United States. In 1882, five universities in this country offered the Ph.D. degree in history and granted two persons that degree. By 1911–12, twenty-two American universities offered the Ph.D. in history and turned out annually twenty-seven recipients of that degree. By 1912, five hundred historians in the United States held the Ph.D. degree. Dexter Perkins et al., The Education of Historians in the United States (New York, 1962), 16–17. [↩]

- About this episode, see Ray Allen Billington, “Tempest in Clio’s Teapot: The American Historical Association Rebellion of 1915,” AHR, 77 (1973): 348–69. [↩]

- For a review of these and other constitutional changes, see “The Evolution of the Constitution,” Perspectives, 22 (May–June 1984): 16–20. [↩]

- DuBois, “The Enforcement of the Slave Trade Laws,” Annual Report of the American Historical Association [hereafter, Annual Report], 1891 (Washington, 1892), 161–74, and “Reconstruction and Its Benefits,” AHR, 15 (1909–10): 781–99. [↩]

- AHA Papers, 1: 40. [↩]

- American Historical Association, Final Report Ad Hoc Committee on the Rights of Historians (Washington, 1975). [↩]

- For example, see Howard K. Beale, ed., The Diary of Edward Bates, 1859–1866 (Washington, 1933); Bernard Mayo, ed., Instructions to the British Ministers to the United States, 1791–1812 (Washington, 1941); Paul Knaplund, ed., Letters from the Berlin Embassy, 1871–1874, 1880–1885 (Washington, 1944); and Grace Lee Nute, ed., Calendar of the American Fur Company’s Papers, 2 vols. (Washington, 1945). [↩]

- Again, see Billington, “Tempest in Clio’s Teapot.” [↩]

- AHA Papers, 1: 49–72. [↩]

- Annual Report, 1900 (Washington, 1901), 39. Even Herbert B. Adams, the leading proponent of institutional history in the United States who blazoned Edward A. Freeman’s motto “History is Past Politics, and Politics are Present History” across the wall of the historical seminary at the Johns Hopkins, took pains to explain that Freeman had been badly misunderstood. “He used the word ‘political’ in a large Greek sense,” Adams wrote. “For him the Politeia or the Commonwealth embraced all the highest interests of man. He did not neglect the subjects of art and Literature.” Adams, “Is History Past Politics?” Johns Hopkins Studies in Historical and Political Science, 13th ser. (Baltimore, 1895), 190. [↩]

- Higham et al., History: Humanistic Scholarship in America (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1965), 111. [↩]

- See, for example, Historical Scholarship in America: Needs and Opportunities, A Report by the Committee of the American Historical Association on the Planning of Research (New York, 1932); Social Science Research Council, Bulletin 54, Theory and Practice in Historical Study (New York, 1946); and Michael Kammen, ed., The Past Before Us: Contemporary Historical Writing in the United States (Ithaca, N.Y., 1980). [↩]

- Since 1962 the AHA has continued this publication for articles; between 1962 and 1973 it published a parallel series for books on American history. There is a cumulative index for Writings on American History. The index and the successor series need to be put on computer tapes and made available to scholars by author, title, and subject. [↩]

- The SAA was a daughter organization of the AHA. On December 2, 1934, the AHA’s Executive Council appointed a special committee consisting of Albert Ray Newsome, then head of the North Carolina Historical Commission, Francis S. Philbrick of the Law School of the University of Pennsylvania, and Robert C. Binkley of Western Reserve University to report on the relationship of the AHA to “the whole problem of documentary publication and of national, state, local and private archives.” The first recommendation in the committee’s report (signed only by Newsome and Philbrick), dated October 15, 1935, was the creation of a self-governing organization of professional archivists, which should enjoy the strong support of the AHA. Annual Report, 1935, 1 (Washington, 1936): 175–77. Newsome was the first president of the SAA. Another active member of the AHA, Julian Parks Boyd, then librarian of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and a future president of the AHA (1964), was the first treasurer of the SAA. [↩]

- AHA Papers, 1: 64. The Library of Congress, under the leadership of Herbert Putnam, soon answered this call. Putnam brought Worthington C. Ford to the library in 1902 to head the recently established Manuscript Division, and Ford soon set under way a program to copy and photograph large quantities of manuscripts in foreign archives pertaining to early American history. Higham, et al., History: Humanistic Scholarship in America, 28–29. [↩]

- Annual Report, 1891, 33–61. [↩]

- Annual Report, 1895 (Washington, 1896), 10. Jameson and a special subcommittee of the AHA tried again, in 1908–09, to secure governmental support for the publication of American historical records. Although President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State Elihu Root supported the proposal, Congress refused to appropriate the money for a national historical commission. Jameson made two other efforts and failed. He then abandoned the project. See Elizabeth Donnan and Leo F. Stock, eds., An Historian’s World: Selections from the Correspondence of John Franklin Jameson (Philadelphia, 1956), 12–13. [↩]

- Annual Report, 1891, 43. [↩]

- Annual Report, 1901, 1 (Washington, 1902): 36. [↩]

- H. G. Jones, The Records of a Nation (New York, 1969), 7–8. Also see Donald R. McCoy, The National Archives: Americas Ministry of Documents, 1934–1968 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1978). [↩]

- Jones, Records of a Nation, 8–10; Victor Gondos, Jr., J. Franklin Jameson and the Birth of the National Archives, 1906–1926 (Philadelphia, 1981); Fred Shelley, “The Interest of J. Franklin Jameson in the National Archives, 1908–1934,” American Archivist, 22 (1949): 99–130; and Dorman and Stock, An Historian’s World, 15–17. [↩]

- Jones, Records of a Nation, 118–19. [↩]

- For a detailed account of the work of the NHPRC to 1968, see ibid., 119–33. For the most recent comprehensive review, see National Historical Publications and Records Commission, Annual Report for 1982 (Washington, 1984). [↩]

- Richard W. Leopold, “The Historian and the Federal Government,” Journal of American History, 64 (1977–78): 5–23. [↩]

- Report of the Committee on Secondary School Studies Appointed at the Meeting of the National Education Association, July 9, 1892 (Washington, 1893). [↩]

- The historian members were, notably, Woodrow Wilson of Princeton University, Edward G. Bourne of Adelbert College, Albert Bushnell Hart of Harvard University, and James Harvey Robinson of the University of Pennsylvania. Charles Homer Haskins and Frederick Jackson Turner, both at the University of Wisconsin, also participated by invitation. For an editorial note on the conference and the minutes of its meetings, see Link et al., Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 8: 61–73. Also see Theodore R. Sizer, Secondary Schools at the Turn of the Century (New Haven, Conn., 1964); and Hazel Whitman Hertzberg, “The Teaching of History,” in Kammen, The Past Before Us, 475. [↩]

- Committee of Seven, The Study of History in Schools: Report to the American Historical Association (New York, 1899), v. [↩]

- Ibid., 134–36. The other members of the committee were Herbert B. Adams, George L. Fox, rector of the Hopkins Grammar School of New Haven, Albert Bushnell Hart, Charles Homer Haskins of the University of Wisconsin, Lucy M. Salmon of Vassar College, and H. Morse Stephens of Cornell University. It should be noted that, among this group, only Fox was connected with a secondary school. It should also be noted that the committee, in its report of 267 pages, emphasized the central role that history should occupy in high school curricula, discussed “the present condition of history in American secondary schools,” surveyed the place of history in secondary schools in German, French, English, and Canadian schools, discussed the proper training of teachers in history in secondary schools, and so on. [↩]

- Committee of Five, The Study of History in Secondary Schools: Report to the American Historical Association (New York, 1911), 64–65. [↩]

- American Historical Association, The Study of History in Elementary Schools: Report to the American Historical Association by a Committee of Eight (New York, 1909). [↩]

- [National Education Association], The Social Studies in Secondary Education (Washington, 1916); and American Historical Association, Report of the Commission on the Social Studies: Conclusions and Recommendations (New York, 1934). [↩]

- Hertzberg, “Teaching of History,” 478–79. [↩]

- “The work of the Commission had little or no effect on the teaching in the high schools.” W. Stull Holt, for the AHA Service Center for Teachers of History, The Historical Profession in the United States (Washington, 1963), 14. [↩]

- Hertzberg, “Teaching of History,” 483. [↩]

- “The Status of History in the Schools,” Journal of American History, 62 (1975–76): 557–70. The quotation is on page 557. [↩]

- For example, see Ernest L. Boyer, High School: A Report on Secondary Education in America (New York, 1983); National Commission on Excellence in Education, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative Need for Educational Reform (Washington, 1983); Theodore R. Sizer, The Dilemma of the American High School (Boston, 1984); and Chester E. Finn, Jr., et al., eds., The Humanities in America’s High Schools (New York, 1984). [↩]

- Donald B. Cole and Thomas Pressly, Preparation of Secondary-School History Teachers (3d edn. rev., Washington, 1983), 27. [↩]

- See, particularly, Warren I. Susman’s last report as vice-president of the Teaching Division, in Annual Report, 1978 (Washington, n.d.), 51–59. [↩]

- Jones, Records of a Nation, 40–65. [↩]

- For the report, with Julian P. Boyd’s “dissenting statement,” see ibid., 275–94. Boyd dissented, he said, because the committee’s original draft had been watered down in its final version. [↩]