Presidential Address

Marking: Race, Race-making, and the Writing of History

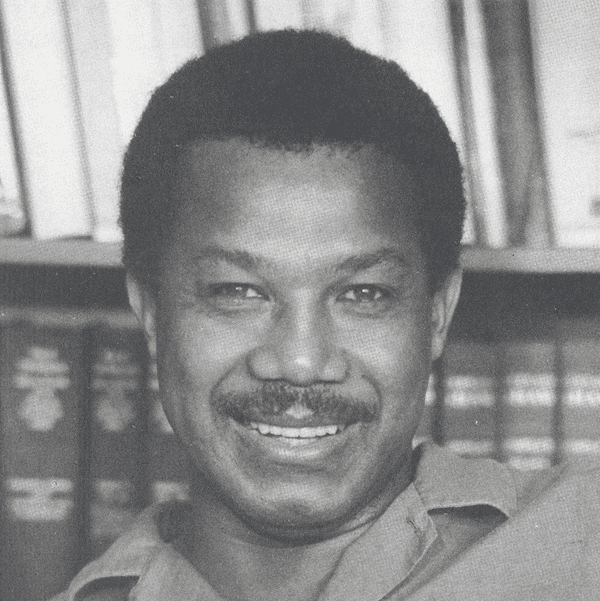

Biography

From the 1994 Presidential Biography booklet

By Rebecca J. Scott, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

We can write no genuine history of the black experience without attempting to see our ancestors face to face, without straining to hear their thoughts and desires, without groping for the textures of their interior worlds. But having done that, we must establish linkages between that interior world and the external developments and movements in the larger world; for only in that way can that history lay any claim to centrality in the national experience … We must do history inside out and back again.1

Tom Holt wrote this in 1983, and in it one sees reflected his formation as a historian and his trajectory as a writer. As a child in Danville, Virginia, he listened to his grandmother’s stories of the African American past while she shelled peas; as a master’s student in English literature at Howard University he read the classic stories of human striving and the poetry of his teacher Sterling Brown. In the 1960s, working as a rural organizer with migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the South, he experienced the problems of political leadership; in the 1970s, he turned these problems into historical questions when he studied with C. Vann Woodward at Yale.

Tom Holt began teaching at Howard University in 1972, the year before he finished his doctorate. He has gone on to teach at Harvard University (1976–1979), the University of Michigan (1979-1987), and, most recently, at the University of Chicago (1987–present). Today he is the James Westfall Thompson Professor of American History at Chicago. From his grandmother’s stories to his most recent work, he has lived and written history “inside out and back again,” eventually tracing the nature of freedom for former slaves from the fields of Jamaica where sugar and bananas were grown to the salons and cafés of London where policy was debated.

Tom Holt has also taught history “inside out and back again.” With undergraduates he has used lived experience to draw students into the study of the most difficult historical phenomena—as in a pioneering seminar at Michigan on race and racism—and then persuaded them that such study requires an extraordinary degree of rigor and self-discipline. With graduate students he has been generous, direct, and demanding. He is willing to entertain the most disparate and ambitious initial ideas—only to insist that the student go on to develop a clear sense of how to pose a question and recognize limits. This, too, comes from his experience. He had himself proposed to C. Vann Woodward an impossibly ambitious thesis project—an analysis of postemancipation society in the United States South and the British West Indies in comparative perspective. Woodward accomplished something few have managed before or since: he stopped Tom Holt in his tracks. The proposal was prudently brought back within the boundaries of the state of South Carolina. Holt reflects that had he actually committed himself to such an unfinishable project as a graduate student, he would likely now be in an altogether different line of work.

The “problem of freedom” was an impossible thesis topic, but Holt wasn’t really stopped. The project became instead a possible life work. Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction, based on Holt’s doctoral thesis, appeared in 1977. By the time he learned that it had won the Sydnor Award from the Southern Historical Association, he had already begun doing fieldwork in Jamaica, tackling comparable questions on an Atlantic scale. His volume, The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor, and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832–1938, appeared in 1992, and has been received with admiration by scholars not only in Britain, the Caribbean, and the United States, but also in Spain and Brazil. It is a model of Atlantic studies in the widest sense, a work in which metropolitan and colonial histories are fused, and in which freedpeople and Crown officials share the stage equally.

Holt’s view of the role of history in public life has animated not only his examination of slave emancipation and its aftermath, but also his own comportment as a scholar. In the midst of finishing the manuscript of The Problem of Freedom, he developed a collaboration with Dennie Palmer Wolf, a researcher at the Harvard School of Education, on the question of how to awaken in adolescents an interest in history. Working with documents written by a committee of freedpeople from Edisto Island, South Carolina, in 1865, and reviewing tapes of student discussions of the documents, he wrote a brilliant pamphlet for teachers titled Thinking Historically: Narrative, Imagination, and Understanding.

That same year, Holt addressed a conference on “the right to literacy,” organized for teachers by the Modem Language Association. His talk, later published as “‘Knowledge Is Power’: The Black Struggle for Literacy,” contrasted the meaning of reading for former slaves and the meaning of formal education for contemporary African American young people. In the first years after slave emancipation, he argued, education carried with it the promise of the exercise of political voice, and was embraced with extraordinary fervor by African Americans. If today there is estrangement between schools and community, the fault does not lie in some imagined “historical deficit” of the black community, for the tradition of attachment to education is clear. It must be sought—and attacked—in contemporary conditions themselves, and in the disjuncture between knowledge and power.

It should not, perhaps, be surprising that Thomas Holt has been willing to engage in the struggle for education in the broadest sense. He began college as an eager young science student planning to major in engineering. In the summer of 1963 he returned to Danville to take a summer job. He recalls listening to the radio with his mother as the first reports of the beatings of civil rights demonstrators at the Danville town hall came over the radio. Toe radio was broadcasting live from the site where Tom’s high school classmates and their fellow demonstrators were being arrested. He and his mother did not speak, but when he left the next morning she knew where he was headed. Four arrests and one conviction later, it was clear that he was not going to become another bright young engineer.

Thirty years later, his scholarly projects still reflect a commitment to come to grips with the possibilities for justice in a divided America. He is preparing a manuscript for the Johns Hopkins University Press on “Race and Racism in American History,” and he has begun a biography of W.E.B. Du Bois. At the same time, he is co-editing a collaborative bibliography, “Sources for the Study of Societies after Slavery,” to help open up the field of postemancipation studies, while expanding an essay on “The Articulation of Race, Gender, and Political Economy in British Emancipation Policy,” that frames new questions for such studies.

Tom Holt has already shown that he can live with the curse “May you live in interesting times.” He increasingly faces its academic equivalent, “May you study burning issues.” His career demonstrates that he has the insight, and grace under pressure, to meet this challenge as well.

Bibliography

A special mission: the story of Freedmen’s Hospital, 1862–1962, by Thomas Holt, Cassandra Smith-Parker, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn. Washington: Academic Affairs Division, Howard University, 1975.

Black over white: Negro political leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction, by Thomas Holt. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

Thinking historically: narrative, imagination, and understanding, by Tom Holt; Dennie Palmer Wolf, coordinating editor. New York: College Entrance Examination Board, 1990.

The problem of freedom: race, labor, and politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832–1938, by Thomas C. Holt. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Beyond slavery: explorations of race, labor, and citizenship in postemancipation societies, by Frederick Cooper, Thomas C. Holt, Rebecca J. Scott. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

The problem of race in the twenty-first century, by Thomas C. Holt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Major problems in African-American history: documents and essays, edited by Thomas C. Holt, Elsa Barkley Brown. 1st ed. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

The Problem of Race in the Twenty-first Century, by Thomas C. Holt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002

Children of Fire: A History of African Americans, by Thomas C. Holt. New York: Hill & Wang, 2010

The Movement: The African American Struggle for Civil Rights, by Thomas C. Holt. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021

Note

- “Whither Now and Why? An Introduction,” The State of Afro-American History: Past, Present, and Future, ed. Darlene Clark Hine. (Louisiana State University Press, 1986), p. 6. [↩]