Presidential Address

Intellectuals and Other People

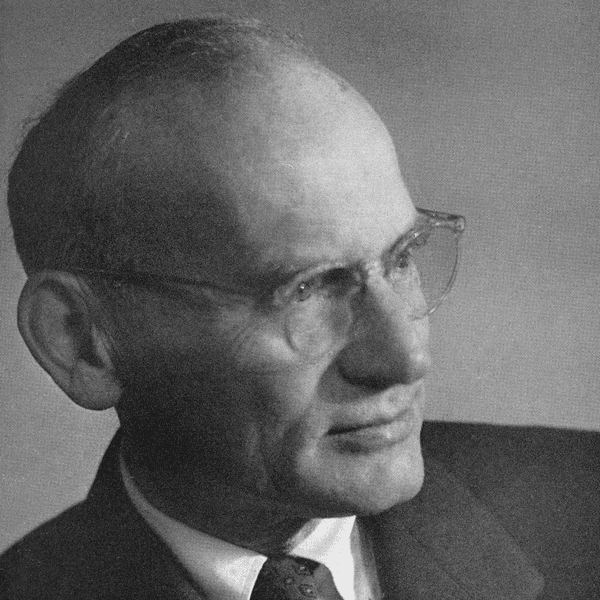

In Memoriam

From Perspectives, May 1996

Merle Curti (September 15, 1897–March 9, 1996), Frederick Jackson Turner Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and a former president of the American Historical Association, died March 9, 1996, at the age of 98. Curti was born near Omaha on September 15, 1897, of Swiss and Yankee ancestry. As a student at Harvard (A.B., 1920; Ph.D., 1927) he studied with Samuel Eliot Morison, Frederick Jackson Turner, Charles Homer Haskins, and Arthur Schlesinger, Sr., who directed his thesis after Turner’s retirement. Bliss Perry of Harvard’s English department encouraged his desire to employ literary sources in historical study—the theme of his first published article in 1922.

Curti taught at Smith College from 1925 to 1937, at Teachers College-Columbia University from 1937 to 1942, and from 1942 to 1968 at Wisconsin, where he directed 86 Ph.D. dissertations. Many of his students, including the late Richard Hofstadter and Warren Susman, became leading scholars in their own right.

Curti’s scholarship is notable not only for its quantity—more than 20 books and some 50 articles—but also for its scope and its pathbreaking quality. His Growth of American Thought (1943), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize, helped define the embryonic field of American intellectual history. In the preface, Curti explicitly distinguished this “social history of American thought” from the work of Arthur O. Lovejoy, whose masterpiece The Great Chain of Being (1936) had adopted an internalist, history-of-ideas approach that largely neglected social context. Going beyond leading writers or thinkers, Curti in this broad-brush synthetic work also tapped a rich vein of popular culture sources, from newspapers to ballads.

The Making of an American Community: A Case Study of Democracy in a Frontier Community (1959), a forerunner of lithe new social history,” examined social mobility in Wisconsin’s Trempeleau County. Based upon tax rolls, census lists, public records, and similar sources, this collaborative study drew upon the work of three graduate research assistants, whose aid Curti acknowledged in the preface and on the book’s title page, together with that of his wife Mar. iro.llimi.et, a psychologist and trained statistician he had married in 1925.

Margaret Curti died in 1961. Of their two daughters, Nancy Alice and Martha (Mother Felicitas Curti, C.S.B.), the latter survives, together with three grandsons and a great-granddaughter. Curti’s second wife Frances Bennett Becker, whom he married in 1968, also predeceased him.

Curti’s own ouevre bears out his oft-stated insistence on the social rootedness of intellectual history. His first book, The American Peace Crusade, 1815-1860 (1929), a revision of his PhD thesis, reflected the prevailing disillusionment with the war propaganda of 1917-18. The Social Ideas of American Educators (1935) and other Depression-era works were sharply critical of capitalism. The Growth if American Thought, by contrast, completed as the Western democracies battled fascism, expressed cautious hopefulness about America’s spiritual prospects. His work of the 1950s, including studies of American philanthropy and the high school textbook America’s History, coauthored with Lewis Paul Todd (first ed., 1950; retitled The Rise of the American Nation in 1961), continued the generally positive tone, reflecting both the times and his own temperament. In the spirit of Turner, Charles A. Beard, and John Dewey—his major intellectual avatars—Curti brought to all his scholarship a secular and humanistic perspective, a respect for pluralism and openness, and a desire to explore and extend the social meaning of democracy.

Some of Curti’s more original work appeared in monographs exploring specific topics, such as the treatise on Lockean thought in America (Huntington Library Bulletin, April 1937); his 1937 edition of the letters of Elihu Burritt, a 19th-century pacifist and reformer; his 1968 essay on the influence of Swedish social thought on New Deal policy makers; and his three American Historical Review articles: on the “Young America” movement of the 1850s (October 1926), on pacifist propaganda and the Treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo (April 1928), and on Americans and world’s fairs (July 1950).

At a 90th-birthday symposium held in Madison in 1987, Paul Conkin observed: “Merle Curti is a more complete historian than anyone else I have ever known. He has a deeper dedication to knowing the human past; a wider curiosity about all aspects of that past; a more single-minded commitment, over a longer period of time, to all the hard work and drudgery involved in telling the story of that past; and a richer, more diverse body of completed scholarship.”

As a leader in the profession, Curti’s maximum influence came in 1936-54, when he prodded the guild to broaden its intellectual scope, demographic base, and social vision. As chair of a Social Science Research Council committee that produced the 1936 report Theory and Practice in Historical Study, he challenged his colleagues’ notorious aversion to theory and called for historians to move beyond the familiar terrain of political, military, and diplomatic history. In 1939-40, first as a member and then as chair of AHA Program Committees, he put these exhortations into practice, helping to assemble convention programs that highlighted methodological issues, social and cultural history, and new kinds of sources such as photography and folk music: Curti’s election as AHA president in 1953 recognized his central role in this ongoing intellectual and social reorientation. Earlier, in 1951-52, as president of the Mississippi Valley Historical Association, forerunner of the Organization of American Historians (OAB), he spearheaded a controversial decision to shift the annual meeting out of racially segregated New Orleans.

Retiring in 1968, Curti remained active intellectually and politically. He read incessantly; entertained a host of friends old and new; and corresponded regularly with former students, shrewdly assessing their work and praising their successes.

Merle Curti’s memory is preserved through the Curti professorship and the annual Curti Lectures of the UW-Madison history department, and by the OAH’s annual Curti Prize for the best book in U.S. intellectual or social history. A 1996 drive to. augment the endowment of this prize produced not only an outpouring of contributions but numerous tributes from former students, many themselves now in advancing years. Wrote Eugene Link, a Curti Ph.D. who taught for many years at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, “None of my teachers were as dedicated to his students as Merle Curti. Well into his nineties, each time I visited with him he tended to say ‘Gene, have you seen … ‘ (something of current importance). Perhaps at age 88, as his oldest living student, I can be proud to say that every hour with him was laced with inspiration.”—Paul Boyer, University of Wisconsin at Madison

Bibliography

Rise of the American nation, by Lewis Paul Todd and Merle Curti. Liberty ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.

Austria and the United States, 1848-1852, a study in diplomatic relations, by Merle Eugene Curti. Northampton, Mass.: Dept. of History, Smith College, 1926.

The American peace crusade, 1815-1860. Durham: Duke University Press, 1929.

Bryan and world peace, by Merle Eugene Curti. Northampton, Mass: Dept. of History, Smith College, 1931.

Peace or war; the American struggle, 1636-1936, by Merle Curti. New York: W. W. Norton, 1936.

The Learned Blacksmith; the letters and journals of Elihu Burritt, by Merle Curti. New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937,

The growth of American thought, by Merle Curti. New York, London: Harper & Brothers, 1943; Reprint with a new preface by the author, New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1982.

The roots of American loyalty, by Merle Curti. New York: Columbia University Press, 1946.

The University of Wisconsin: a history, by Merle Curti & Vernon Carstensen. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1949; 1999.

American scholarship in the twentieth century. With essays by Merle Curti. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953.

A history of American civilization, by Merle Curti, Richard H. Shyrock. Others New York: Harper, 1953.

Prelude to point four; American technical missions overseas, 1838-1938, by Merle Curti and Kendall Birr. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1954.

Probing our past, by Merle Curti. New York: Harper, 1955.

American paradox: the conflict of thought and action. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1956.

The making of an American community; a case study of democracy in a frontier county, by Merle Curti, with the assistance of Robert Daniel. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959.

The social ideas of American educators, with new chapter on the last twenty-five years. Paterson: Pageant Books, 1959.

American philanthropy abroad, by Merle Curti; with a new introduction by the author. New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1988.

The American nation: Reconstruction to the present, by Lewis Paul Todd, Merle Curti. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986.