Presidential Address

In Memoriam

Excerpts from the American Historical Review 43:2 (January 1938)

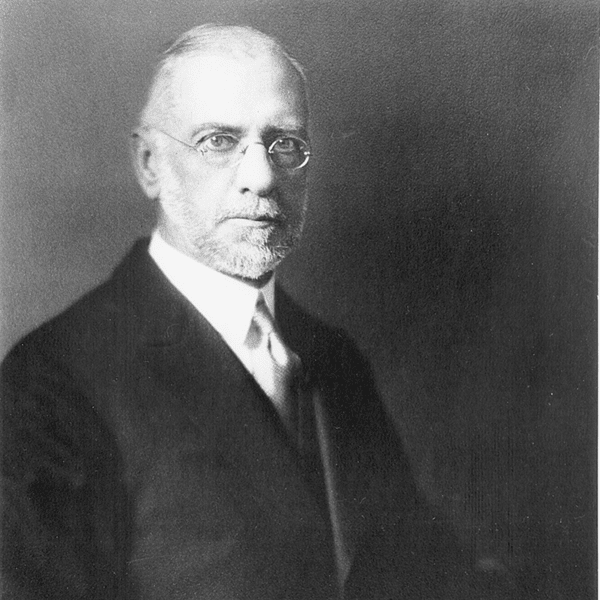

John Franklin Jameson (September 19, 1859–September 28, 1937). With the death of Dr. J. Franklin Jameson, on September 28 last, there passed from our midst the master whose far-ranging services to the cause of history had given him a unique position in our profession, a position all the more unassailable because it was unsought, unclaimed, and unofficial. We shall not see his like again, if only because the circumstances under which his work was done will never recur. He had no predecessor, and he will have no successor.

Jameson was born near Boston on September 19, 1859. From the Roxbury Latin School, where he received his early education, he went to Amherst and was graduated in the class of 1879. In college he developed what was to remain his dominant interest through life, and he decided to prepare himself for the career of a professor of history at a time when there were few university chairs in that subject in the United States. With this object in view he entered the recently founded Johns Hopkins University, where he studied under the guidance of Herbert B. Adams and received the doctorate in 1882. He remained at Hopkins, as assistant and associate in history, for six years. In 1888 he was appointed Professor of History in Brown University and served in that position till 1901, when he was called to the University of Chicago to succeed Hermann Eduard von Holst as Professor and Head of the Department of History. In 1905 he was appointed Director of the Department of Historical Research in the Carnegie Institution of Washington and held that office until his retirement from it in 1928, when, in his seventieth year, he became Chief of the Division of Manuscripts in the Library of Congress and first incumbent of its newly established chair of American history. He never gave up active work. In the spring of 1937 he suffered a severe accident while crossing a street in Washington, but after a period of pain and tedious inertia, borne with philosophical resignation and great good humor, he was able, though still on crutches, to resume his work, and his colleagues in the Library of Congress looked forward to years of continued association with him. His final illness, an attack of pneumonia, was brief. He died virtually in harness.

When young Jameson decided to make history his life work the historical profession in this country was just coming into existence. There were probably not more than fifteen persons of professorial rank in the United States who were giving all their time to history. It was still a wide-spread opinion in college and university circles that history, in so far as it ought to be taught at all, should be auxiliary to some other subject. It was not until 1884 that a group of scholars and friends of history, meeting at Saratoga, established the American Historical Association, which was to become the most effective agency in the advancement of American historical scholarship. In the list of its original members Jameson’s name appears with those of such older scholars as Charles Kendall Adams, Mellen Chamberlain, Moses Coit Tyler, Andrew D. White, and Justin Winsor; more nearly his contemporaries but still his seniors were Herbert B. Adams, to whom chief credit belongs for the conception of a nation-wide historical organization, Ephraim Emerton, and Edward Channing. Throughout the history of the Association Jameson was its most continuously active and devoted member. Recognition came to him in his election to the Executive Council in 1900. In 1904 he was elected Second Vice-President of the Association and so, in due course, became President in 1907. Thereafter, as ex-President, he continued to be an active member of the council and to render many and invaluable services. His keen interest in the affairs of the Association never flagged, and he attended the annual meetings and the meetings of the council with a regularity reminiscent of his Puritan ancestors’ churchgoing. The accounts of the annual meetings that he wrote for the April numbers of the American Historical Review constitute an informing and thoughtful commentary, lit up by occasional flashes of dry humor, on the progress of historical studies in the United States. His interest in the younger members of the Association, probably unknown to most of them, was always keen. He realized the importance of their work for the future of the historical profession. An evidence of this interest was the compilation which he began, as a personal enterprise, of the lists of doctoral dissertations in progress, and which he edited year after year for the benefit of the graduate schools of the country until it reached its present rather alarming proportions.

Jameson rendered one of his most important services to the cause of history in the United States as Managing Editor of the American Historical Review, in which capacity he served for nearly thirty years—from the founding of the Review in 1895 to 1901 and again from 1905 to 1928. The very first number set a standard in the quality of its articles and reviews and in the editorial skill disclosed that might well have made it the despair of Dr. Jameson’s successors. … Jameson made the Review not only a vehicle for historical publication and criticism but a clearinghouse for historical ideas and enterprises, and through it he exerted a powerful and beneficial influence upon the historical profession, which was of the utmost importance at a time when younger men and women were entering it in numbers. To his pre-eminent qualifications for the higher ranges of editorial work Jameson added a capacity for taking infinite pains. Proof was read with conscientious care, no detail was so trivial that it escaped his attention, none of the minutiae, so trying and unrelenting in their demands, was slighted.

Those who knew him well not only respected and admired him—they loved him. To his colleagues in the Library of Congress and to his intimates in the American Historical Association, as well as to other friends and to the members of his family, his death brought the sense of deep personal bereavement.

Bibliography

An introduction to the study of the constitutional and political history of the States. By J. Franklin Jameson. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins press, 1886; Reprint, New York, Johnson Reprint Corp., 1973.

Encyclopedic dictionary of American reference. By J. Franklin Jameson and J.W. Buel De luxe library edition, 2 vols. Dictionary of U.S. history. Boston, 1901.

Letters on the nullification movement in South Carolina, 1830–1834. Edited by J. Franklin Jameson. New York, 1901.

Gaps in the published records of United States history. By J. Franklin Jameson. New York, 1906.

Narratives of New Netherland, 1609–1664. Edited by J. Franklin Jameson; with three maps and a facsimile. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909.

Dictionary of United States history; alphabetical, chronological, statistical, from the earliest explorations to the present time; based upon the original work prepared in 1893 by J. Franklin Jameson. Rev. ed., edited under the supervision of Albert E. McKinley. Philadelphia, Historical publishing company, 1931.

The American Revolution considered as a social movement. New York, P. Smith, 1950, 1926.

An historian’s world; selections from the correspondence of John Franklin Jameson. Edited by Elizabeth Donnan and Leo F. Stock. Philadelphia, American Philosophical Society, 1956.

Essays in the constitutional history of the United States in the formative period, 1775–1789. New York, Da Capo Press, 1970.

An introduction to the study of the constitutional and political history of the States. Baltimore, N. Murray, publication agent, Johns Hopkins University, 1886. New York, Johnson Reprint Corp., 1973.

Essays in the constitutional history of the United States in the formative period, 1775–1789. By graduates and former members of the Johns Hopkins University; edited by J. Franklin Jameson. Reprint, Buffalo, N.Y.: W.S. Hein Co., 1986, 1889.

John Franklin Jameson and the development of humanistic scholarship in America. Edited by Morey Rothberg and Jacqueline Goggin; foreword by William E. Leuchtenburg, James H. Billington, and Don W. Wilson. 3 vols. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993-2001.