Presidential Address

Some Suggestions to American Historians

In Memoriam

From the American Historical Review 68:3 (April 1963)

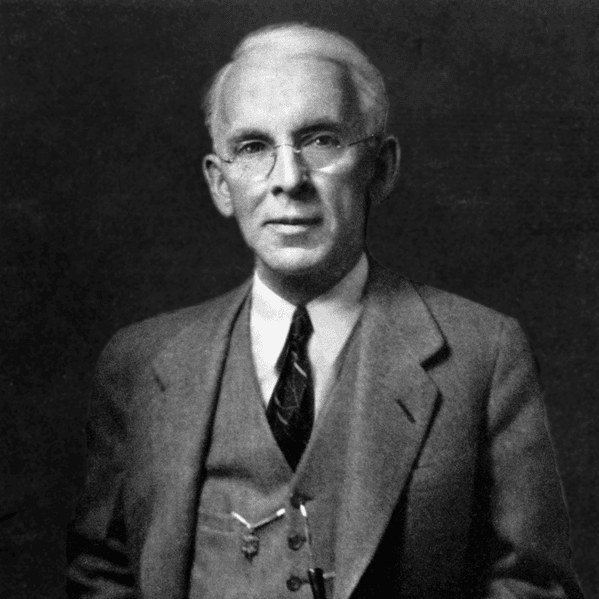

Guy Stanton Ford (May 9, 1873–December 29, 1962) was born at Liberty Corners, Wisconsin, on May 9, 1873; he died on December 29, in the Washington apartment he and Mrs. Ford had occupied since 1941. Between those dates and places stretched a life crammed with contributions to the improvement of historical teaching and research, the maturing of higher education in all its facets, and the inculcation of a sense of community in, as well as between, the “disciplines.” To Ford, as to maybe a dozen other men of his generation, the term “academic statesman” can justly be applied.

Ford’s preparation for a teaching career ran through Upper Iowa University; Wisconsin, where such men as Ely and Turner were sowing their new seed; three years of public school teaching; Germany, mostly in Berlin (1899–1900); Columbia University, and so in 1903 to the Ph.D. and the publication of his thesis Hanover and Prussia, 1795–1803: A Study in Neutrality.

Yale appointed him instructor in 1901 and assistant professor in 1906. Illinois promptly outbid Yale with the offer of its new chair in modern European history, and at thirty-three Ford returned to the Midwest. At Urbana the quality of his scholarship was made evident in his teaching, in the critical appraisals of a dozen books, written for this Review, and in modern history “conferences” at Annual Meetings of the Association. Illinois was moving rapidly from gawky “underdeveloped” adolescence to maturity, and Ford helped to steer it through those exciting years. When, therefore, Minnesota’s turn came to transform itself from “an overgrown New England College of the West” into a modern state university, George E. Vincent, the dynamic new president, learned of Ford’s Illinois record and in 1913 offered him the dual job as chairman of the history department and dean of the virtually nonexistent graduate school at Minnesota.

Ford held the first position till 1931. For the first few years he carried a “full teaching load,” ranging from the Freshman European survey course to Senior-graduate classes on Prussian history and Bismarck. He built up his staff, which already included such men as A. B. White and Wallace Notestein, by luring S. J. Buck, A. C. Krey, and C. W. Alvord from Illinois. Then, as throughout his career, he had an uncanny capacity for spotting promising young teachers and researchers, for attracting them to Minnesota, and for doing his utmost to keep them there. A tireless “fisher of men,” he did not confine himself to United States waters; nor did he limit his catch to historians.

In his spare time he worked on his study of Stein and the Era of Reform in Prussia, 1807–1815, which appeared in 1922. But spare time grew increasingly scarce as “Get Ford!” became a way of solving problems for more and more people or institutions. The Association put him on the Executive Council in 1915; on the “Special Committee on History and Education for Citizenship in the Schools” in December 1918, just when he was ending two years’ hard labor as head of the Division of Civic and Educational Publications in George Creel’s Committee on Public Information; on the Board of Editors in 1920, and as chairman of that Board, 1921–1927; on the “Krey” Commission for Investigation of Social Studies in the Schools in 1929; and in the presidential chair in 1937. Outside our guild he served on the Social Science Research Council (1923–1940), was a director of the National Bureau of Economic Research for some years and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. The Laura Spellman Foundation sent him to Germany in 1924 to see what could be done to restore university efficiency; the Guggenheim Foundation kept him on its advisory council from 1925 till his death. Harpers chose him to edit their “Historical Series,” and he was editor in chief of Compton’s Pictured Encyclopaedia.

To all these tasks Ford brought a quick awareness of the essentials of a situation or problem, a dislike of the grandiose or spectacular, an ability to persuade people to work together for common ends, and what has been called a “winking shrewdness and good temper.” In return he learned much about the trends and forces in public and academic life, noted the men of ideas and promise in the many fields he surveyed, and won the good will of the foundations for the university whose rebuilding from the very basement up was his chief continuing purpose. In that work his main role was as right-hand man to two great presidents and as trusted colleague of a group of very able deans. Of the many accomplishments of this team Ford was especially responsible for the development of the graduate school and of the university press. In each case the story was one of “rags to riches,” except that in the beginning there was no money for buying rags. In each the growth in size, quality, and prestige was rapid. The graduate school’s enrollment climbed from 175 in 1913 to 3,300 in 1938, the year when Ford completed a quarter of a century’s work as its dean. His colleagues celebrated this silver jubilee by presenting him with a volume, beautifully produced by the eleven-year-old press, containing a collection of his own essays and articles, aptly entitled On and Off the Campus. The regents capped this testimonial by appointing him president of the university.

Three years later, at sixty-eight, he retired from that position and for twelve years served as Executive Secretary of the American Historical Association and editor of its Review. During those years the Association’s membership increased, while its opportunities, problems, and responsibilities grew immeasurably. Every challenge was met by a valiant response, and when Ford retired at eighty in 1953, it could be said that one more major job had been well done. Yet he was not finished. Physical frailty came slowly and imperceptibly, but the intellectual vigor and range impressed those who still persisted in asking, and getting, his aid and counsel to the very end. Economists and statesmen today stress the need for “full employment” and “high productivity.” Ford enjoyed the former, in both senses of that verb, throughout his life. And if you are searching for monuments to his productivity, look around you—full circle.

Bibliography

Essays in American history, dedicated to Frederick Jackson Turner. New York: H. Holt and Company, 1910.

War cyclopedia: a handbook for ready reference on the great war. Ed. by Frederic L. Paxson, University of Wisconsin, Edward S. Corwin, Princeton University, Samuel B. Harding, Indiana University. Washington, Govt. Print. Off., 1918.

Stein and the era of reform in Prussia, 1807-1815, by Guy Stanton Ford. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1922.

Compton’s pictured encyclopedia. 10 vols. Chicago: F. E. Compton & Company, 1924.

The European powers and the Near East, 1875-1908, by Mason Whiting Tyler. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1925.

Science and civilization, by Guy Stanton Ford. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1933.

Dictatorship in the modern world, edited by Guy Stanton Ford. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press, 1935.

Stein and the era of reform in Prussia, 1807-1815. Gloucester, Mass.: P. Smith, 1965, 1922.

Hanover and Prussia, 1795-1803; a study in neutrality. New York: AMS Press, 1967.