Excerpts from the American Historical Review 76:4 (October 1971)

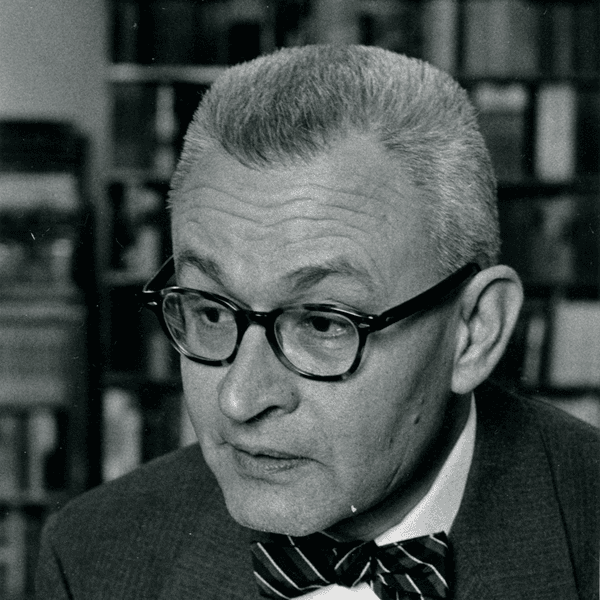

David Morris Potter (December 6, 1910–February 18, 1971), president of the American Historical Association and Coe Professor of History at Stanford University, died of cancer on February 18, 1971, at the age of sixty-one. At the time of his death he was also president of the Organization of American Historians. On his desk was the nearly completed manuscript of his study of the coming of the Civil War, which was intended for publication in the New American Nation series and on which he had been working for over a decade.

Although death cut down David Potter at the height of his career and powers, but before the publication of what would have been his masterwork, his life and work had already had widespread impact. For Potter’s influence in the profession derived from more than his scholarly work, important as it is; it flowed also from the man himself. Few people-students or professional colleagues-who came into contact with him remained unaffected by the experience.

David Potter was born on December 6, 1910, in Augusta, Georgia; he attended schools there until 1928, when he left for Emory University. At Emory he was a debater, a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and a companion of C. Vann Woodward. After obtaining the BA from Emory in 1932 Potter began his graduate studies at Yale under another Georgian, U. B. Phillips; Yale awarded Potter the PhD in 1940. Meanwhile he had begun his teaching career in his native South, spending two years at the University of Mississippi and four years at Rice Institute. When his dissertation appeared in print in 1942 as Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, he returned to teach at Yale, where he remained for nineteen years. It was during his long tenure at Yale that he revealed his diverse talents and high sense of duty to the institutions he served. At different times, for example, he was editor of the Yale Review and director of the program of American studies at Yale. During those same Yale years Potter went abroad to be Harmsworth Professor at Oxford and to Chicago to deliver the Walgreen Lectures, which were later published as his best-known book, People of Plenty (1954).

In 1961 Potter moved to Stanford University, where he was Coe Professor of American History and, for three years, executive head of the history department. During his years at Stanford Potter also journeyed to lecture posts in England and the United States. He gave the Commonwealth Fund Lectures at the University of London in 1963 under the general title “The Compulsions of a Voluntaristic Society: Individual Freedom and Its Limitations in American Life.” In 1968 he delivered at Louisiana State University the Walter Lynwood Fleming Lectures under the title “A Century of the Concurrent Majority.” At Stanford, as at Yale, Potter contributed his time and talents to the work of the university and the department, serving on time-consuming appointive committees and elective faculty bodies, some of which were important and others of which were not. But Potter was never one to stand on his prestige; he served when and where he was needed.

His professional life had its paradoxical aspects. He was a professional historian in the fullest and best sense of the phrase. He loved teaching and writing history; he reveled in the conventions, in the shop talk, in the gossip; he willingly served on the boards of editors of the Pacific Historical Review, the Mississippi Valley Historical Review, and the Journal of Southern History and on the governing bodies of the Southern Historical Association, the American Historical Association, and the Organization of American Historians, among others. Yet he never confused a commitment to truth or to decency toward another human being with a commitment to the profession. As few men can do, David Potter could see himself, his work, and his colleagues in historical perspective; that is, he was rarely impressed, though always appreciative.

It may seem paradoxical, especially in an obituary in a professional journal, but it is true, nonetheless, that the loss of the distinguished historian should seem smaller than the loss of the man. To say this is not to diminish Potter’s acknowledged stature as a historian but rather to record the remarkable fact that his character matched his eminence as a historian.—Carl N. Degler, Stanford University

Bibliography

Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1942, with a new preface in 1962.

People of Plenty: Economic Abundance and the American Character. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1954.

The American Round Table Discussions on People’s Capitalism. Yale University, 1957.

Nationalism and Sectionalism in America, 1775-1877. New York: Holt, 1961.

The South and the Sectional Conflict. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1968.

History and American Society: Essays of David M. Potter, ed. by Don E. Fehrenbacher. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York: Harper & Row, 1976