Presidential Address

Written History as an Act of Faith

In Memoriam

From the American Historical Review 54:2 (January 1949)

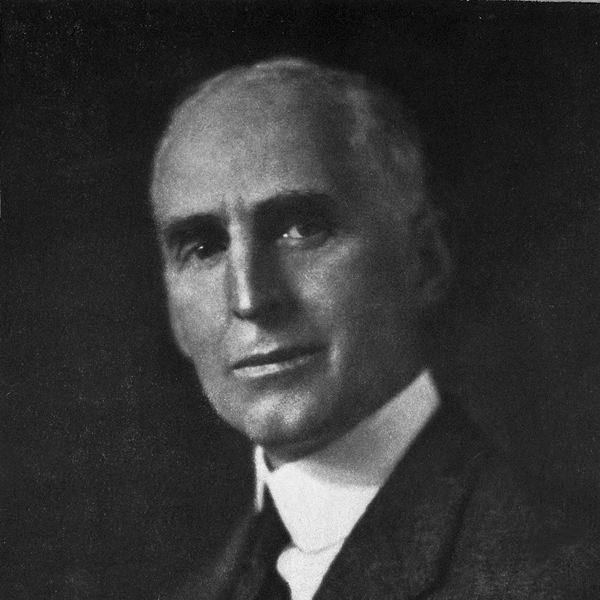

Charles A. Beard (November 27, 1874–September 1, 1948) was one of the most daring and innovative historians of his day. It is with sorrow that we must record the death, on September 1, 1948, of an honored former president and wise counselor of the American Historical Association, Charles Austin Beard, in the seventy-fourth year of his age. A native of the Hoosier State, who never forgot his early years in the Middle West, he was graduated in 1898 from DePauw University, which conferred upon him nineteen years later the honorary degree of doctor of laws. A postgraduate year of study at Oxford directed his attention to the history of English local government during the Tudor period, and he investigated various county records under the guidance of Professor F. York Powell. Returning to this country, he continued his researches in history and government first at Cornell and then at Columbia, where Professors Goodnow and Osgood urged him to complete his doctoral thesis, The Office of Justice of the Peace in England (1904). His careful appraisal of the origin, nature, and significance of that office reminded some of his readers of the great Coke’s remark: “It is such a form of subordinate government for the tranquillity and quiet of the realm as no part of the Christian world hath the like.” From 1904 to 1917 Dr. Beard taught at Columbia, serving successively as lecturer in history, adjunct professor of politics, associate professor, and professor of politics; but no departmental lines or academic barriers hemmed in his inquiring mind. With James Harvey Robinson he wrote The Development of Modern Europe (1907) and compiled the Readings to accompany it-two volumes which many a college teacher soon came to regard as indispensable texts. His American Government and Politics (1910) and American City Government (1912) challenged conventional approaches and placed more emphasis on the forces generating political action than on the resulting institutional forms. There were some historians who took exception to his Contemporary American History (1914), regarding the title as self-contradictory; but he maintained that the recent past deserved more careful scrutiny than it was then receiving from scholars trained in the techniques of historical research. His remarkable talents as a teacher-his closely reasoned analysis and his skillful presentation of evidence, his sharp definitions, and his witty deflation of pomposity and pretense-brought him groups of superior students, who became his devoted friends, perennially sought his advice, and affectionately thought of him as “Uncle Charlie.”

The demands of teaching, however exacting, could not stifle his scholarly impulses. The publication of An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution (1913), for which he thought he “received more whacks than praise,” made him the central figure in a sharp controversy, but it slowly changed the point of view of historians concerning the framing of our fundamental law. Nothing has yet superseded his clinical dissection of the Hamiltonian system or his exposition of the reasons for the growth of Jeffersonian dissent, which he set down in his Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy (1915). Although Beard was not an economic determinist and never resorted to the Marxian dialectic, he was deeply concerned with the interrelations of economics and government and their manifestations in political action. Explaining his position, he wrote: “It. was largely by recognizing the power of economic interests in the field of politics and making skillful use of them that the Fathers of the American Constitution placed themselves among the great practicing statesmen of all ages and gave instructions to succeeding generations in the art of government.” Perhaps the most explicit statement of his views, however, appeared in his Economic Basis of Politics (1922).

After he resigned from the Columbia faculty, Beard bore a hand in the establishment of the New School of Social Research, served for five years (1917–1922) as director of the Training School for Public Service in New York, and became adviser to the staff of the Tokyo Institute of Municipal Research. In the critical days following the Japanese earthquake (1923), Viscount Geto, minister of home affairs, called upon him for counsel in planning municipal reconstruction projects. Meanwhile, with his wife, Mary R. Beard, he was at work on a multivolume study of American life. The publication of the first two volumes, The Rise of American Civilization (1927), brought a chorus of praise, with scarcely a discordant note. The Beards were impressed with the unique character of American society, and they felt that it could make its highest contribution to world civilization only if it retained its freedom of action, independent of any alien civilization. They said this with even greater emphasis in America in Mid-Passage (1939) and The American Spirit (1942), which may be regarded as the third and fourth parts of their classic. “Continentalism” became a fundamental thesis in many of Charles Beard’s provocative discussions of the foreign policy of the United States, and it runs like a self-strengthening thread through such studies as The Idea of National Interest (1934), The Open Door at Home (1934) and American Foreign Policy in the Making, 1932-1940 (1946). Disliking the idealistic internationalism of Woodrow Wilson almost as much as the imperialistic principles of the Mahan-Theodore Roosevelt-Beveridge school, Beard looked back with nostalgia toward happier days-to the period before what he liked to call the “breach with historic continentalism.”

The pressure upon him to take a more active part in public affairs was terrific, but he managed to resist. His writing ever came first; and we are the richer that he held to his purpose. Nevertheless; he responded generously whenever any of his fellow scholars called for help. The manuscripts which he read and criticized would make a considerable collection; the pages of this journal reveal his kindness to successive editors. He found time to serve the American Historical Association as president (1933), and he carried the same burden for the American Political Science Association (1926) and the National Association for Adult Education (1936). He spurred on the Social Studies Commission of the American Historical Association; and he wrote that part of the commission’s report known as A Charter for the Social Sciences in the Schools (1932), which a well-qualified critic has described as “the most significant document in American education since the days of Horace Mann.”

Many of Charles Beard’s friends felt that in the later years of his life he had come to doubt that mankind could .learn much through the methods and purposes of the professional historians; yet in the July, 1947, issue of this journal he wrote: “Although we cannot know universal history or any large part of it, we may, apparently, learn a great deal more about history and ourselves, by taking thought, considering the limitations of our historical knowledge and increasing the precision of our methods.” Nothing in Beard’s writings quite reveals the radiant personality of the man. Perhaps, in the Socratic dialogues which he called The Republic (1943), one may see how brilliantly he could guide the course of conversation, how quickly his mind went out to those who asked questions intelligently, how generous he could be in sharing with others the erudition that he wore so lightly. At the hilltop farm near New Milford, Connecticut, he and Mary Beard always had a welcome for the wayfarer who sought knowledge and inspiration.

Bibliography

The office of justice of the peace in England, in its origin and development, by Charles Austin Beard. New York: Columbia University Press, Macmillan Company, agents: London: P. S. King & Son, 1904.

European sobriety in the presence of the Balkan crisis, by Charles Austin Beard. New York: American Branch of the Association for International Conciliation, 1908

American government and politics, by Charles A. Beard. New York: Macmillan, 1910.

American city government; a survey of newer tendencies, by Charles A. Beard. New York: Century, 1912.

The Supreme court and the Constitution. New York: Macmillan, 1912; Reprint, Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 1999.

American citizenship, by Charles A. Beard and Mary Ritter Beard. New York: Macmillan, 1914.

Contemporary American history, 1877-1913, by Charles A. Beard. New York: Macmillan, 1914.

National governments and the world war. New York: Macmillan, 1919.

The history of the American people, by Charles A. Beard and William C. Bagley. New York: Macmillan, 1920.

History of the United States. New York: Macmillan, 1921

The economic basis of politics, by Charles A. Beard. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1922; Reprint, with a new introduction by Clyde W. Barrow. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 2002.

Economic origins of Jeffersonian democracy, by Charles A. Beard. New York: Macmillan, 1927.

The rise of American civilization. 2 vols. New York: Macmillan, 1927.

Whither mankind: a panorama of modern civilization. Edited by Charles A. Beard. New York: Longmans, Green, 1928.

The Balkan pivot: Yugoslavia; a study in government and administration, by Charles A. Beard and George Radin. New York: Macmillan, 1929.

The American leviathan: the republic in the machine age, by Charles A. Beard and William Beard. New York: Macmillan, 1930.

A century of progress, edited by Charles A. Beard. “First edition.” Chicago and New York, Harper & Brothers in coöperation with a Century of progress exposition, 1932.

America faces the future, edited by Charles A. Beard. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1932.

The myth of rugged American individualism, by Charles A. Beard. New York: John Day, 1932.

The future comes; a study of the New Deal, by Charles A. Beard and George H.E. Smith. New York: Macmillan, 1933.

Whither mankind: a panorama of modern civilization. Edited by Charles A. Beard. New York City: Blue Ribbon Books, 1934.

The idea of national interest: an analytical study in American foreign policy, by Charles A. Beard, with the collaboration of G.H.E. Smith. New York: Macmillan, 1934; Reprint, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977.

The nature of the social sciences in relation to objectives of instruction, by Charles A. Beard. New York, Chicago [etc.] C. Scribner’s Sons, 1934.

An economic interpretation of the Constitution of the United States, by Charles A. Beard, with new introduction. New York, The Macmillan company, 1935; Reprint, Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 2001.

The presidents in American history, by Charles A. Beard. New York: J. Messner, inc., c1935; Reprint, Charles A. Beard’s the presidents in American history: George Washington to George Bush. Rev. ed., updated by William Beard and Detlev Vagts. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: J. Messner, 1989.

The devil theory of war; an inquiry into the nature of history and the possibility of keeping out of war, by Charles A. Beard. New York: The Vanguard Press, 1936.

Jefferson, corporations and the Constitution, by Dr. Charles A. Beard. Washington: National Home Library Foundation, 1936.

America in midpassage. New York: Macmillan, 1939

Giddy minds and foreign quarrels; an estimate of American foreign policy, by Charles A. Beard. New York: Macmillan, 1939.

The making of American civilization, by Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard; color illustrations by Stanley M. Arthurs. New York: Macmillan, 1939.

A foreign policy for America. New York, London: A.A. Knopf, 1940.

The American spirit, a study of the idea of civilization in the United States. New York: Macmillan, 1942.

American foreign policy in the making, 1932-1940; a study in responsibilities, by Charles A. Beard. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1946.

President Roosevelt and the coming of the war, 1941; a study in appearances and realities. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1948; Reprint, with a new introduction by Campbell Craig. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2003.

The office of justice of the peace in England, in its origin and development. New York, B. Franklin, 1962; Reprint, Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 2001.

The enduring Federalist, edited and analyzed by Charles Beard. New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co., 1959.

More than a historian: the political and economic thought of Charles A. Beard, by Clyde W. Barrow. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2000.