About the Briefing

This handout was created for the AHA’s December 11, 2025, Congressional Briefing on the history of federal science funding. Panelists Melinda Baldwin (Univ. of Maryland), Arthur Daemmrich (Arizona State Univ.), and Bhaven Sampat (Johns Hopkins Univ.) discussed the history of the federal government’s approach toward science in public policy, and how the government has supported and funded scientific research and innovation over time.

Overview

The United States has invested in science since the nation’s founding. Today’s research system grew out of Congressional responses to evolving national needs, geopolitical competition, and key scientific and technological breakthroughs. Competing visions of national strategic goals have sparked debates and compromises over what science to support, how to fund it, and who sets research priorities. The resulting mix of federal departments and agencies that fund basic research and carry out mission-oriented science has been lauded for underpinning global scientific leadership as well as criticized for its bureaucracy and increasingly risk-averse funding culture.

1790–1900: Building Practical Science and National Capacity

1790 – Congress passes the first US patent act, encouraging invention and creating a new system of intellectual property.

1803 – Congress funds the Lewis & Clark expedition, which maps the West, identifies plant and animal species, and describes unique geologic formations.

1807 – The US Coast Survey becomes the first civilian scientific agency, supporting navigation and defense.

1843 – Congress funds Samuel Morse’s telegraph demonstration line through a $30,000 appropriation, helping launch US telecommunications.

1846 – Congress establishes the Smithsonian Institution as a public-private partnership. It quickly becomes a center for research and public science and later evolves into a museum complex.

1840s–90s – Scientific associations including the American Association for Advancement of Science (AAAS), the American Chemical Society (ACS), and the Geological Society of American (GSA) are founded, strengthening the nation’s scientific community.

1862 – The Department of Agriculture is established and begins collecting agricultural statistics and conducting basic chemical and botanical analyses. The Morrill Act established land-grant colleges, funded agricultural science, and supported knowledge transfer to farmers.

1863 – Congress charters the National Academy of Sciences to advise the government on scientific and technical matters.

1879 – The US Geological Survey is founded to map the nation and standardize measurements.

1887 – The Hygienic Laboratory is established, which would evolve into the National Institutes of Health.

1900–60: Federal Agencies and the Rise of Basic Research

1906 – Congress passes the Pure Food and Drug Act, leading to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration, which establishes technical standards and new laboratory methods alongside its regulatory role.

1917–18 – World War I spurs new federal science coordination through the National Research Council and military research offices.

1923 – The US Navy builds the Naval Experimental and Research Laboratory (later renamed the Naval Research Laboratory).

1939–53 – US federal spending on science increases by a factor of 25 (adjusted for inflation).

Early 1940s – World War II mobilization—including penicillin development and the Manhattan Project—anchors federal leadership in large-scale research and development.

1944 – Senator Harley Kilgore introduces legislation for a postwar National Science Foundation, funding basic and applied research with strong political accountability.

1945 – Vannevar Bush’s Science–The Endless Frontier published; proposes a National Research Foundation run by scientists.

1945-50 – “Bush-Kilgore debates” in Congress and in scientific journals explore competing visions for science planning, control of funds and their dissemination, geographic distribution of funding, and priority setting for basic versus applied research. The Atomic Energy Commission was established in 1946, the National Institutes of Health is renamed in 1948, and the National Science Foundation is created in 1950.

1958 – After Russia’s launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957, NASA and the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, later renamed DARPA) are created, expanding federal support for space, defense, and engineering research.

1960s–90s: Reassessment, Retrenchment, and New Science Policy Debates

1966 – The Department of Defense’s Project Hindsight report questions the payoff of basic research and elevates applied science.

Late 1960s/early 1970s – Federal science funding declines for the first time since World War II, sparking concern that science funding is no longer a priority for the federal government.

1973 – President Nixon clashes with the National Institutes of Health over the direction of cancer research and with his science advisors over numerous issues. He abolishes the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) and the Office of Science and Technology and fires the NIH director.

1975–76 – Economic pressures lead to cuts at NSF; Congress passes the National Science and Technology Policy Act, creating the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP).

1980 – Congress passes the Bayh-Dole Act, allowing recipients of federal grants to obtain patents, and the Stevensen-Wydler Act, supporting tech transfer from national laboratories to private sector and state and local governments.

1980s–90s – President Reagan emphasizes basic research and defense technologies; major initiatives including Star Wars and the Superconducting Super Collider highlight tensions over both basic and applied science. The end of the Cold War shifts federal priorities to health (including the Human Genome Initiative), economic competitiveness, and information technologies.

2000–Present: Security, Innovation, and Crisis Response

2002 – Congress passes the Homeland Security Act, establishing the Department of Homeland Security by combining all or part of 22 federal departments and agencies.

2000–10s –National security concerns drive growth in defense science and technology; NIH budget doubles, and biotech and digital technologies gain prominence.

2020 – Operation Warp Speed accelerates COVID-19 vaccine development, echoing earlier wartime mobilization models.

2022 – CHIPS and Science Act authorizes funding for semiconductor manufacturing, research, and education programs and establishes the Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) Directorate at the NSF and its regional innovation engines program.

Mid-2020s – New debates revisit the balance of basic and applied research and the federal role in funding and managing university-based research, technology development and transfer, and alignment with national development strategies.

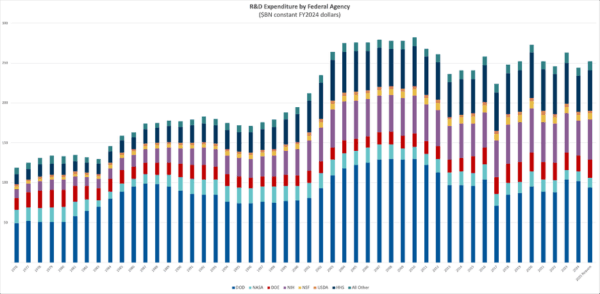

Federal R&D Budgets, 1976-present

Source: Adapted from AAAS Federal R&D Budget Dashboard (https://www.aaas.org/programs/r-d-budget-and-policy/historical-rd-data).

Participant Biographies

Melinda Baldwin is the AIP Endowed Professor in History of Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland, College Park. She holds a BS in chemistry from Davidson College, an MPhil in history and philosophy of science from the University of Cambridge, and a PhD in history from Princeton University. Her research examines how scientific authority is constructed and communicated, especially through journals, peer review, and the institutions that define expertise. She is the author of Making “Nature”: The History of a Scientific Journal and the forthcoming book In Referees We Trust? How Peer Review Became a Mark of Scientific Legitimacy.

Arthur Daemmrich is director of the Arizona State University Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes and a professor of practice in the ASU School for the Future of Innovation in Society. He holds a BA in history and sociology of science from the University of Pennsylvania and a PhD in science and technology studies from Cornell University. His research focuses on innovation, regulation, and the evolution of the federal science and technology policy profession. He previously directed the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation and has held appointments at the University of Kansas School of Medicine and Harvard Business School.

Bhaven Sampat is an economist at Johns Hopkins University, with faculty appointments at the School of Government and Policy and the Carey Business School, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). He holds a BA and PhD in economics from Columbia University. His research examines the history and political economy of innovation policy, federally funded research, patent policy, and the US biomedical research enterprise. He has published on how public funding, patent law, and institutional design shape drug development, university–industry technology transfer, and long-run scientific and economic outcomes. He previously held appointments at Arizona State University, Columbia University, New York University, and Georgia Tech.

The AHA is grateful to the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State University and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for their sponsorship of this briefing.

![]()

Related Resources

January 1, 2026

Choosing a Career Pathway

January 1, 2026

What Can You Do with That History Degree? Exploring the Data

January 1, 2026