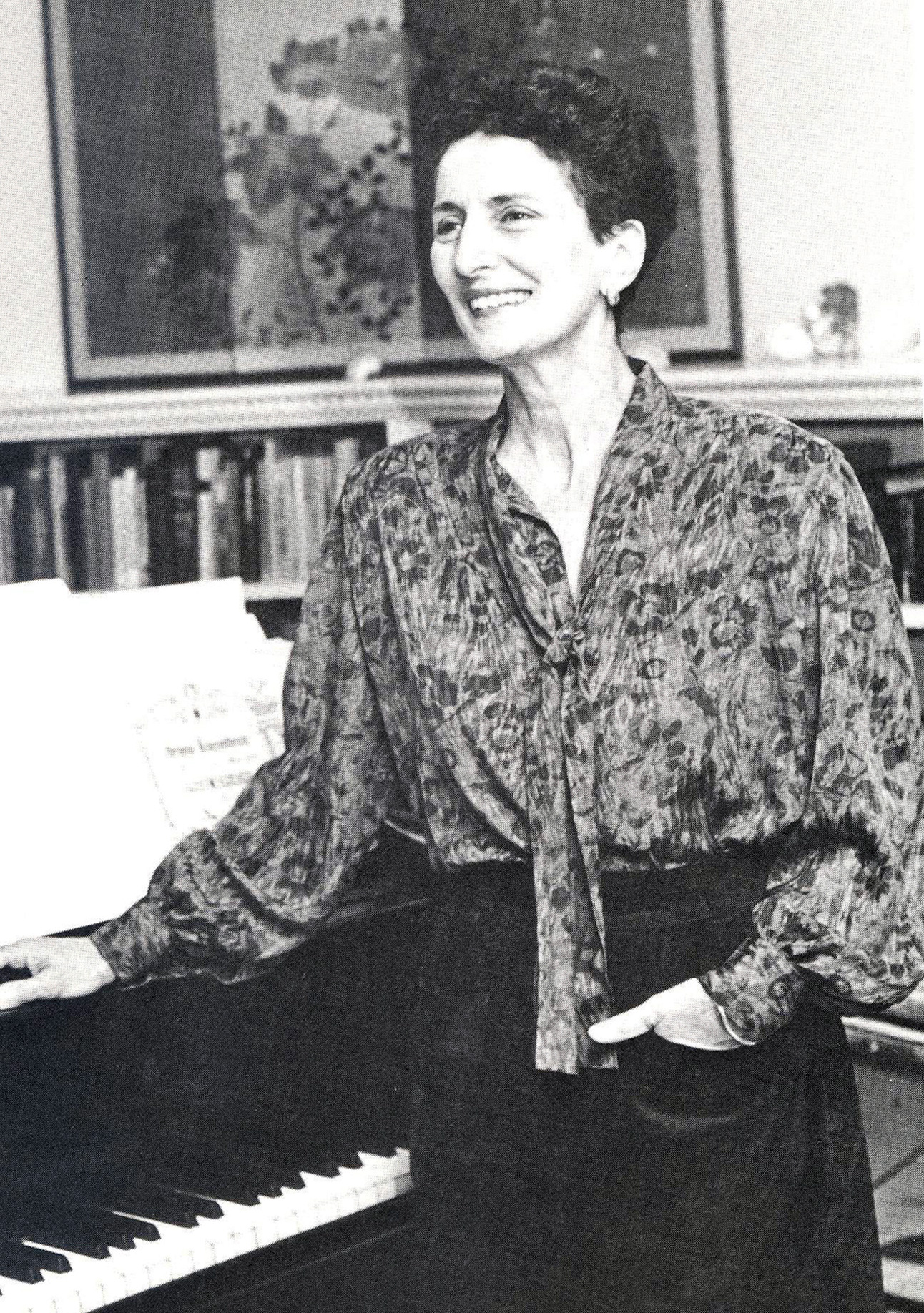

Natalie Zemon Davis (1928–2023)

Historian of France; Former AHA President and 50-Year Member

Natalie Zemon Davis was the most renowned anglophone historian of early modern France of her generation. She was born in Detroit, Michigan, on November 8, 1928, and died in Toronto, Canada, on October 21, 2023, at age 94. Davis served as president of the American Historical Association in 1987, only the second woman to be elected.

After completing her undergraduate studies at Smith College and pursuing graduate study at Radcliffe College and Harvard University, she completed her PhD at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in 1959. She taught at Brown University; the University of Toronto; the University of California, Berkeley; and from 1978 to her retirement as the Henry Charles Lea Professor at Princeton University. Over the course of her career, she received 19 honorary degrees as well as countless awards, including the Holberg International Memorial Prize (2010) and the National Humanities Medal (awarded by President Barack Obama in 2013). As astonishing as her record of professional recognition is, it tells us little of why she was so singular and why her death has left the historical discipline worldwide so bereft.

I had the privilege of studying with Professor Davis (affectionately known to her students as NZD) at Princeton University in the 1980s. I still remember a comment Professor Davis wrote on one of my research papers: “You have learned to widen your lens, now learn to move the tripod.” Davis’s remarkable corpus of work—eight research monographs; many, many other writings; and film, television, and theater projects—had a transformative impact in academia and beyond. This is because she knew how to move her tripod, and she kept it on the move for more than 50 years. The first move was from the views on reformed faith espoused by the likes of Jean Calvin and Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples to those of the printing workers and working women in the city of Lyon. The next was from the opinions of judges of the Parlement de Toulouse to those of Bertrande de Rols, the peasant wife of the errant Martin Guerre. From there, she moved on to women navigating other geographic, religious, and cultural margins—Glikl bas Judah Leib, Marie de l’Incarnation, and Maria Sibylla Merian. In her later years, she traveled further still to capture the transnational and interstitial worlds of the Muslim apostate Leo Africanus and the Jewish Romanian linguist Lazare Sainéan.

Davis was a Europeanist by training but an internationalist by both intellectual predilection and political conviction. She was methodologically heterodox, incorporating anthropological and literary approaches as well as social and political theory into her work. She “used the theories and methods she needed” to do the work she needed to do, as her friend Edward P. Thompson once wrote in private appreciation. In her historical imagination, there were no dark parts of the globe and no stories unworthy of being heard or being told. She plumbed archives on five continents of those in the highest echelons of social and political power (see Fiction in the Archives: Pardon Tales and Their Tellers in Sixteenth-Century France) as well as the traces that have been left by the persecuted and immiserated. She was a genius at reading sources across the grain for what they unwittingly revealed rather than overtly professed. She sought out, above all, the forgotten and the overlooked.

This dedication to the margins translated into her professional ethos and commitments as well. I happened to be at her office hours when the White House telephoned to recruit her to dinner with President Ronald Reagan and French president François Mitterrand and heard her reply politely that regrettably she was “busy teaching on that day.” As sought after as she was, in any lecture hall, conference, or seminar, her gaze and her attention turned to the youngest or the most underrecognized person in the room. She treated all her students, undergraduate or graduate, as junior research partners. She edited and translated sources for them to work with, and she only taught courses on her current research. Her most transformative course was Society and the Sexes, a first in introducing the history of women into university curricula. During my studies with her, the topic was gift giving in 16th-century France, a theme that captures the reciprocity that was at the heart of her pedagogy.

At least two prizes and one endowment have been created to honor and perpetuate Davis’s legacy. As she said at the conclusion of one of the many conferences organized to honor her retirement, “The gift keeps on giving.”

Carla A. Hesse

University of California, Berkeley

Tags: In Memoriam Europe

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.