When Garry Smith visited Western Australia’s Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages in 2013 to retrieve copies of his great-grandmother’s death certificate, he was shocked. The word “Aboriginal” had been removed. Previously, when he had searched online, he had found a certificate from 1915, originally inscribed “Kitty Aboriginal”; in the printed copy, it was just “Kitty.” When Smith and a relative of his asked why the word had been removed, they were told that it was because “Aboriginal” was an “offensive” term. Smith’s great-grandmother’s identity had been “whited” out. Smith said later that the erasure made him feel sick, as if he was expected to be ashamed of being Aboriginal. He also feared that this might create more obstacles for those who make native title claims to Australian land and waters.

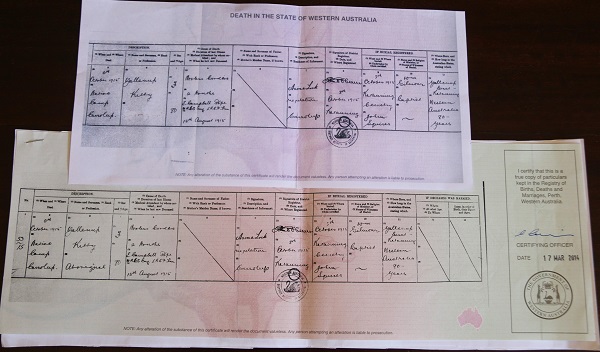

A side-by-side comparison shows a copy of Garry Smith’s great-grandmother’s original death certificate with the word “Aboriginal” (bottom) and another copy with the word redacted (top). Courtesy Garry Smith

In order to research indigenous histories, Aboriginal families, legal researchers, and historians rely heavily on text-based archives, even though they cover limited time scales. Many colonial and state archives were created out of imperial sovereignties and continue to work within colonial historical periodizations. As Smith’s case implies, archives are, however, mutable in many ways. The controversy also raises another question: Can the archive ever be buttressed against offense? Historians are acutely aware that state archives are curated sites reflecting historical and ongoing power structures. Archives are a conversation between those who created them, the people whose records they contain, the archivists who organize and regulate access to them, and the changing audiences who use them.

Last year, after Smith lodged a complaint of racial discrimination with the state registrar, the issue of the redacted word reignited. Both the History Council of Western Australia and the Western Australian Genealogical Society accused the state registrar of tampering with history. Jenny Gregory, president of the History Council, stated: “No one should change the past.” The registrar’s office responded that its obligation was to provide only specified data and that “Aboriginal” was not the only term it censored. Words such as “bastard,” “illegitimate,” “half-caste,” and “incinerated”—presumably for cremated stillborn babies—were all deemed offensive. Applicants can obtain true copies of originals, but only if they sign a statutory declaration stating that they will not be offended.

The word “Aboriginal” has a specific history in Australia. Early British arrivals to the southern continent in the late 18th century used the terms “Indians,” “Natives,” and “Australians” to describe its inhabitants. The generic term “Aboriginal”—meaning having lived in a place since the earliest known time—eventually attained standard usage in legislative terminology. In Australia, for its different land-owning and linguistic groups, of which there were once 500, the word took on new meanings.

The word “Aboriginal” has become a proud badge of pan-continental identity.

The term “indigenous” appeals to many because it is used in international human rights discourse and includes Torres Strait Islanders, but many first Australians prefer “Aboriginal.” Archaeological evidence points firmly to their ancestors having lived in what was once the greater continent of Sahul for approximately 60,000 years. British colonization and intermarriage across colonizing boundaries led to complex transgenerational identities; race-based descriptors such as “quadroon,” “half-caste,” and “octoroon” that were used in related legislation are now also deemed highly offensive. “Aboriginal,” on the other hand, has become a proud badge of pan-continental identity. To be officially recognized as Aboriginal, individuals have to prove some indigenous ancestry endorsed by a suitable Aboriginal community organization.

In 1915, when Smith’s great-grandmother passed away, Aboriginal people lacked full citizenship in Australia and were subjected to various restrictive laws that governed their residential, marital, and parental rights. These “protective” laws were gradually lifted in the 1960s and ’70s, and in 1992 the High Court of Australia declared that the concept of terra nullius—wasteland or land belonging to no one, which had justified the refusal to create treaties—was a “historical fiction.” With these changes, Aboriginal people had less incentive to obscure their identities, and the power of written documents was heightened; a historical death certificate could serve as the proof required to access certain privileges and legal entitlements.

Smith’s story is but one demonstration of bureaucratic interventions attempting to renegotiate the past and the present. Many Aboriginal people research their family history, especially because of Australia’s historical policies of child removal. The records often contain material that is derogatory, cruel, and heartless. To ameliorate the trauma that these records can cause, some agencies greatly restrict access; others employ counselors. The Queensland State Archives, for example, has Aboriginal officers on hand to de-identify or to block out personal names in materials that are deemed offensive. The underlying principle behind this practice, which enables researchers to view sensitive materials, was that research is potentially useful, knowledge is power, and records should be accessible. These processes work efficiently and potentially add value to the research process.

Until the Australian national government took over responsibility for Aboriginal policy in the 1970s, state governments were responsible for all Aboriginal policy (except in the Northern Territory). Consequently, state archives hold most of the key archival records relating to Aboriginal families. Many governmental departments, libraries, and archives have now become strict gatekeepers of the past. Several delay or block access to written and visual records containing indigenous content. Whether this flows from an admirable ethic of redress against past intrusions or mere risk aversion against offending someone, these practices impede research. Sometimes obstacles preventing access have stemmed from a fear of enabling state-funded entitlements, including the release of information that might lead to remedial justice—for example, compensation for earnings unjustly seized by government trusts or related to the emotional cost of child removal. While the records themselves do not necessarily change, archives mediate the ways in which they permit different audiences of the present to access them.

Each time someone looks at materials in an archive, the past erupts, creating a new imprint on the multilayered ground of the present. We have seen how, a century and more later, a word used to enable state surveillance has become associated with pride in identity. The word “Aboriginal” may be a modern English word, but it now describes people with an exceptionally long, enduring history. To say that one has been in a place since time immemorial, that one is Aboriginal, is a powerful assertion—not only politically and legally, but historically.

Indigenous leaders have long recognized the importance of text-based historical practices to their sovereign entitlements and their future well-being. In the 1830s, under threat of removal from his community’s sovereign lands, Cherokee chief John Ross set out to create an official archive of Cherokee history. He asked the literary figure John Howard Payne to collect histories from the old chiefs and write them down. The state of Georgia confiscated this archive and imprisoned both men. Fortunately, the manuscripts were returned, ending up in the Newberry Library.

Smith’s story demonstrates how bureaucratic interventions attempt to renegotiate the past.

The story of removing the word “Aboriginal” from the public archival record gives us an opportunity to reflect upon the archive’s intermediary role in a changing present. But it is not only the state that is blocking our vistas of the past. Our profession’s love of the text-based archive has meant that historians have allowed these institutions too much power not only in setting our subject matter, but also in concreting the time frames of history. Antoinette Burton has pointed out in her book Archive Stories (2005) that for women’s history, it is imperative to look beyond the state archive. This is also true for indigenous history. Historians, however, have been slow to appreciate the great unwritten archives beyond those of the colonizer state. Perhaps this is because these other kinds of sources are perceived as too unstable, too mutable, or simply too hard to decipher. Yet historians have proved adept at developing rigorous techniques for using oral and visual history, material objects and geographical insights. If historians fail to research and preserve the deep history archive, a whole chunk of Aboriginal and indigenous time will continue to be left out of our history books.

Aboriginal people continue to enact their own modes of historical practice. Aboriginal archival practices are largely landscape-based and transmitted via three-dimensional performances. Their archive lives on in rock art, artifacts, and a living memory that is spoken, sung, danced, painted, crafted, filmed, and digitized (see deepeninghistories.anu.edu.au). The artifacts, hearths, and burials that surface in the present reach out beyond nation state–based periodizations. Indigenous peoples maintain detailed narratives of the ancient past. Cultural and language revivals are reinvigorating these deep histories from indigenous memory—ancient rock art is re-engraved, stories reframed across generations. Geographers and linguists are increasingly interested in the climatic, ecological, and astronomical knowledge of those who lived through the Holocene and the Pleistocene and adapted to both dramatic events and slower change over deep human time.

Controversy over the term “Aboriginal” reminds us not only of the curated nature of government archives, but also of the self-delimiting thinking of historians who are stuck within the imperial time zones of state archives. As historians, perhaps it is our great love for the written archive that is partly to blame for trapping us in the shallow end of time and for creating a historia nullius spanning 60,000 years. Surely this is a greater offense than the use of a word that historically stole privileges and that now, through native title rights, allows at least some to be returned?

Ann McGrath is distinguished professor and Kathleen Fitzpatrick ARC Laureate Fellow at the Australian National University.

Update, March 7, 2019: A previous version of this story noted that Garry Smith’s great-grandmother was born in 1915. Instead, that was the year she passed away. Perspectives regrets the error.

Update, March 20, 2019: This article originally implied that the original archival documents related to Garry Smith's great-grandmother Kitty were altered. Instead, the copies provided to Smith were. The text of this article has been clarified.

Tags: Viewpoints Archives Asia/Pacific Indigenous History

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.