AHA Topics

Research & Publications

Thematic

Cultural, Military, Public History, Visual Culture

Geographic

Asia

Episode Description

Historian Alexis Dudden and graphic artist Kim Inthavong discuss their collaborative work on history, memory, and activism in Okinawa, Japan. Their piece, “Okinawa: Territory as Monument,” appears in the History Lab section of the September issue of the AHR. Inthavong’s graphic panels illustrating Okinawans’ present-day struggle over US military presence in the islands can be previewed below.

Daniel Story

Hi, I’m Daniel Story. This is History in Focus, a podcast by the American Historical Review. In the September issue you’ll find in the History Lab section, a piece by historian Alexis Dudden and graphic artist Kim Inthavong. Comprised of prose, photographs, and five graphic panels, it tells the story of Okinawa, Japan, a collection of islands set just to the south of the Japanese mainland. Home of the independent Ryukyu Kingdom, the islands were annexed by Japan in 1879. During World War II, they were the site of the United States’ initial invasion of Japan and host to the horrifically bloody Battle of Okinawa. Following the conclusion of the war, Okinawa remained under US control until 1972. And still today, there remains an outsized US military presence that many Okinawans view as a threat to their own safety and to the safety and vibrancy of the diverse ecosystems of their islands and bays, controversies that have coalesced in recent years around the construction of a new US base on the shores of the beautiful and ecologically sensitive Oura Bay near the town of Henoko. Alexis and Kim’s piece explores this fraught history, its echoes in the present, and how Okinawan territory itself—it’s very soil—has served as monument to these struggles. This is Episode 6, Soil and Memory.

Alexis Dudden

My name is Alexis Dudden. I’m Professor of History at the University of Connecticut. I teach classes in modern Japan, modern Korea. And I’ve been fortunate to sort of have half of my intellectual life, adult intellectual life, spent in Japan, Korea, and especially Okinawa. Okinawa is one of the most beautiful places on earth. It’s in the East China Sea between the southern main island of Japan Kyushu and Taiwan. Okinawa, the word, actually it’s one of the Ryukyu islands. The Ryukyu kingdom was an independent kingdom until it was forcibly annexed into the Empire of Japan in 1879. When I say one of the most beautiful, interesting places on earth, there are records of human habitation stemming back 30,000 years, fabulous music, a different language from Japanese, several different languages. So this is just a really interesting blend of people from the Pacific and has come to create a wonderful place that is really important today. Okinawa itself, the history of Okinawa, has been remarkably peaceful until the 20th century. Insofar as these are small islands, there are hundreds of them, and incredibly important to the trading nexus of China, Japan, Korea, Philippines. And so what has become the names of the countries we know have had ships that have long pulled into port, and the strength of Ryukyu history and the Ryukyu kingdom was the ability to negotiate with everybody. And then all of a sudden nationalism kicks in, and it has to become part of an empire and colonized. And so it’s an essential territory for the Washington security community. It’s an equally essential territory for Japanese strategists who regard it as the sacrificable spot. The question of who’s occupying whom right now is really at the fore in Okinawa today.

Alexis Dudden reading

Over 70% of the land in all of Japan designated exclusively for US military use is in Okinawa, a prefecture that comprises just 0.6% of the entire country. The United States government still controls 20% of Okinawa’s total surface area. Over half of the 54,000 American troops based in Japan together with their 45,000 dependents and an additional 8000 civilian contractors attached to the US military live in these small islands. Accidental military plane and helicopter crashes into schools and residential areas, toxic chemical spills, drunk driving hit and runs, and sex crimes by American troops against locals are disproportionately high compared to other parts of Japan, all made more complicated because the violence is woven into daily life. Taken together, Okinawan territory has become monument to the islanders modern experience as much as the many important commemorative statues and structures there.

Alexis Dudden

I have to give a shout out to AHR‘s new editor, Mark Bradley, who’s come up with this idea for the monuments series. And he suggested a monument project. And I began to think, okay, there are tons of monuments around Asia—he was not specific. It could have been a contested statue, it could have been a grave site. And then my head was really in Okinawa when we got in touch. And I said, How about this? I’ve been working on another project, a graphic novel called Cargo about a Chinese slave mutiny in 1852. So my head is really visually understanding history right now. And I said to Mark, would it be possible to have AHR do a graphic series and include a lot of visual materials? And Mark was all in right away? I got in touch with Kim and said, “Can we do this?”

Kim Inthavong

And I said, “Absolutely. That sounds super cool.” My name is Kim Inthavong. I’m a full time software developer and freelance illustrator. I didn’t know much about the history going in. But being able to talk with Alexis, given that maybe history wasn’t my strongest subject growing up, and being more of a visual learner, she’s showing me articles, and photographs that were like what was happening and helped me really understand what that history was and how important it was to the people of Okinawa. It was a little bit of trial and error trying to figure out what color wants to go with. For the Cargo projects that we worked on, which focused on the Robert Brown mutiny, the pop of color that resonates through that was the blue and turquoise as well as yellow. I was able to still pull that same color palette into the Okinawa project as it shares the same sea.

Alexis Dudden

And Kim also did a really good job with faces and animals and just the violence of the sea when it goes dark. And what Kim has also just underscored is the mixing of colors that have produced the people and the history there, which is in contrast to the home territory of Japan. And Okinawans to this day also refer to themselves in different racial terms—Uminchu versus Yamato-jin. And so this is something that Kim’s eye, her skill as an artist, really just glommed on to right away.

Kim Inthavong

Since I’m hired more as like a freelance illustrator, my first and foremost is starting to visualize. So I really appreciate when I’m sent pictures, articles, and especially even article headers. I’ll include a lot of photographs from current day to past events. So for Alexis, for every single panel, she gave me about a sentence or more describing the concept that she wanted, like a topic sentence in a way, and instead of me writing a paragraph, I illustrated a picture.

Alexis Dudden reading

Dirt and the changing meaning of soil. In 1958 a high school baseball team from then still American occupied Okinawa participated for the first time since the end of World War II in Japan’s annual Koshien All Star Tournament. Koshien Stadium is near Kobe in central Japan, where the competition has taken place almost without exception since 1924. Babe Ruth played there during his 1934 whirlwind tour of the country. Prior to 1945 Okinawan teams regularly participated together with teams from Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria, as parts of the Japanese Empire. New in 1958, however, was the issue of exactly what Okinawans were in post Imperial Japan as the US occupation rendered them essentially stateless. The buildup to the August 1958 tournament was full of goodwill and high spirits in the mainstream Japanese press, welcoming the teenagers from Okinawa Shuri High to the mainland. Following tradition, the team scooped up stadium soil as a souvenir to take home after its loss in a first round elimination game. Regardless of emotions involved, officials in charge cited US plant and quarantine law and forced the boys to trash their mementos before boarding the plane. Mainland soil was “unclean” in American Okinawa and barred from entry to the island.

Alexis Dudden

That’s just one of those moments of when the state to state interaction misses the point so, I will say, violently. You’ve got the Shuri High Okinawan team, and they get to go to Koshien, which is Japan’s major summer event. Or it used to be. This is the Yankees and Red Sox, but it’s high school. And it’s huge. And the Okinawan team was participating and the boys scooped up the dirt, only to be told by the officials that the dirt is unclean. They’re told that it’s against the United States’ plant and quarantine law. Because at that point, mainland Japan is considered dirty for the Americans living and occupying and owning Okinawa.

Alexis Dudden reading

US territorial rules of control blocked at the Okinawan teenagers’ attempt to belong to some imaginary idea of Japan and instead hit home the law of the land: Japan was less than America, and Okinawans were neither.

Debate in Okinawa over the ongoing construction of a new US base near the islands Northeastern town of Henoko focuses on several factors, and again soil has emerged in telling ways. From the start, Higa Seijun organized fellow townspeople in Henoko, into an action that became known as the “Inochi o Mamorukai”, Society for the Protection of Life. This placed emphasis right away on the meaning of life in terms of multiple living forms inhabiting shared and mutually constitutive surroundings. As part of the effort, Okinawan photographer Ishikawa Mao and writer Urashima Etsuko collaborated on a book called The Island is Rocking, to chronicle the resistance effort, including sit-ins at the front gates of Camp Schwab and kayak protests in Oura Bay aimed at drawing attention to the endangered dugong threatened with extinction by construction. Scuba divers have taken underwater photographs tracking destruction of the coral reefs and eelgrass ecosystem, while Oura Bay, once a World Wildlife Fund, is intentionally devastated. Locals make clear: the ocean helped us raise our children, selling it as a base brings punishment from the gods. In 2010, the joint US-Japan Security Consultative Committee, SCC, finalized plans for a V-shaped runway in the bay’s emerald waters. With construction underway, soil took on a leading role. The committee announced that the new “V-shaped facility (will) be approximately 205 hectares in size and approximately 160 hectares of sea area would be reclaimed, requiring 21.0 million cubic meters of fill; approximately 78.1 hectares of marine plants and approximately 6.9 hectares of coral would be impacted.”

Alexis Dudden

When I say this is just a construction project to nowhere, I really mean that, because the government of Japan as of last Fall has published its own report describing the seabed as mayonnaise—they’re using the English word in Japanese, “mayonnaise.” And it’s sinking already. Yet the project, because it’s been decided between the governments, is going to continue. So they have to turn the mayonnaise into something that can support the cement pillars necessary to be the undergirding to this V-shaped runway. Several years ago when this mayonnaise-like consistency was really understood, dirt started to be imported from mainland Japan. And that’s where environmental activists, scientists said “No, this is this is a biodiverse area. No, you’re going to dump in dirt that’s not from here.” The more recent event is the Japanese government responded to this criticism about dirt from the mainland by saying okay, we’ll scoop up dirt from the Southern part of Okinawa Island and dump it in. But that’s exactly where most of the death occurred during the American invasion of Okinawa in the Battle for Okinawa. And so, activists who run a project called Gamafuya (“the Cave Diggers”) have staged protests increasingly in the last two years saying, “No, there are still bones here. We still haven’t been able to bury the dead.” The soil itself, through their action, has become a challenge to who counts as Japanese. You know, what is the relationship to what Japan can say to the presence of the US military.

Daniel Story

So maybe that takes us to the graphics. I have them here in front of me. Do you guys I presume have access to them?

Alexis Dudden

Yes.

Kim Inthavong

There are five images. So the way that this project was approached is that Alexis gave me a topic sentence, roughly, for each one. And then from there, I wrote, or I illustrated, what I saw from it. I still have those topic sentences, like that original email.

Daniel Story

Do you want to start with the topic sentence for panel one? Do you have that?

Kim Inthavong

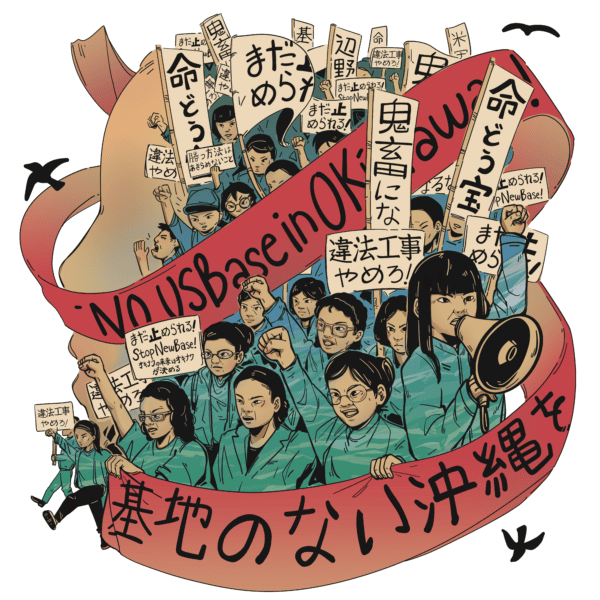

Yes, I do. So for panel one, I was given the following sentence. “In 1995, three US marines gang raped a 12 year old girl. No rape is worse than another. Some generate widespread protests.” From those three sentences, I imagined a sea of protesters.

Sounds of 1995 Okinawan protesters shouting.

I wanted to capture the faces and the movement of the people protesting and just the emotions, anger, and just the feeling of this large group of people uniting against what is a very tragic incident. So in the image, I was inspired by actually an artist called Kim Jung Gi. His bold use of line work, especially in his art piece commemorating the 1919 Independence Movement of Korea, had this sea of people united together in this crowd formation. So in this image, I wanted to capture a similar crowd. But this time, the faces of Okinawa. [I] drew the images all black and white first, and then I colored the bodies blue. This blue represents the sea and its importance to the people, while using a warm color at the base to represent the land and its people, going back to Alexis talking about how important the sea and ocean is and is the beauty it holds. That’s why I wanted to use this color throughout all five images. In this image, I also include the silhouette of the victim actually on the left hand side. I wanted to keep a silhouette of her. Her tragic experience sparked a movement. However, to respect her privacy and personal autonomy, I chose to only illustrate a silhouette while keeping her presence at the foundation to this piece. The last important part about this piece are the signs and the signage for the main banner. I chose a direct phrase coined by the movements itself, “no US base in Okinawa” and its translation in Japanese. I also pulled the color red from the flag of Okinawa and decided to use this as another key color and focal point throughout all five pieces. The signage includes both verbiage from the 1995 protests and current day activism.

Alexis Dudden

Kim, I really appreciate how you’ve just explained your drawing, your illustration, because it does bring it alive. Equally interesting to me working with Kim is Kim has not studied Japanese language. She took exceptional care to get the writing right as it were. Your eye is so spot on that, you drew it beautifully. You drew the protest banners beautifully.

Kim Inthavong

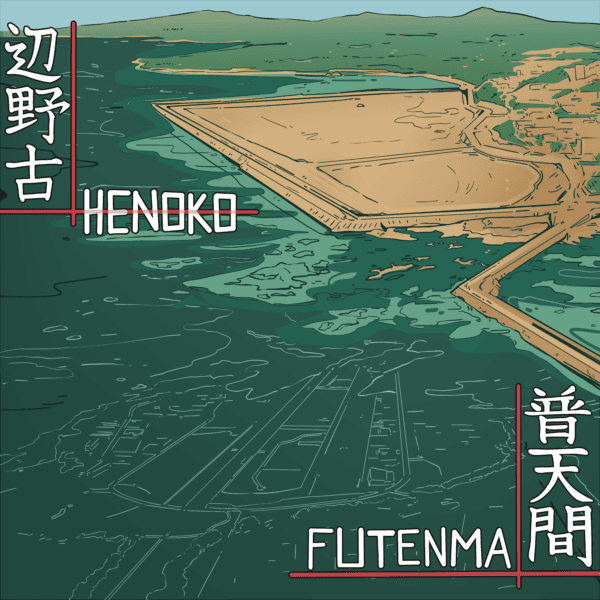

So the topic sentence for panel two was “Bait and Switch: the Futenma Base for a new base offshore of Camp Schwab in Oura Bay near the town of Henoko.” So in this piece, I wanted to highlight both military bases, and after discussion with Alexis, I decided to emphasize the Henoko Base construction in contrast to the already completed Futenma base. To quote Alexis, Futenma is more well known and distinguished in comparison to Henoko. So I decided to flip that on its head for this piece and have Futenma just be its own outline in the sea, while Henoko is bold, and what I think the main focus of this project wants to talk about. One important note about this piece is the Henoko text is crossed out. This is to represent how the construction of the Henoko base is a complex and ever changing situation that has been and continues to be resisted by the people of Okinawa.

Daniel Story

Oh, wow. Yeah, I’ve seen aerial photos of the Futenma base. And wow, I see it now. Another brilliant subtlety that is so powerful when you pull it out like that.

Kim Inthavong

Thank you so much.

Alexis Dudden

As I said, we’re not going to be able to afford Kim in a couple of years.

Kim Inthavong

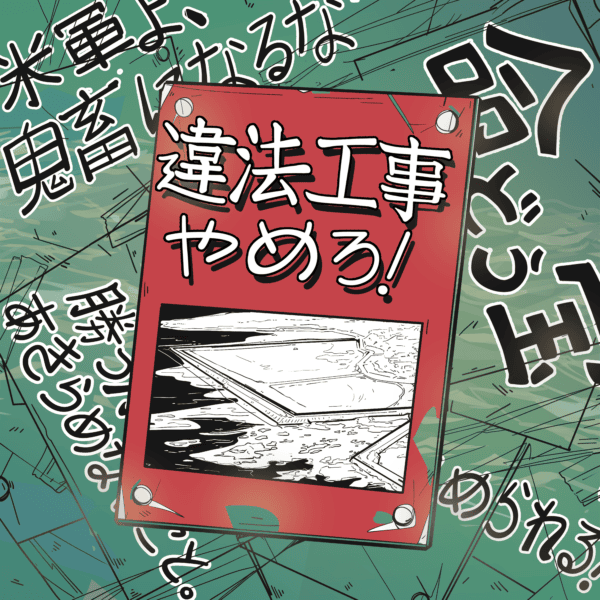

The topic sentence for panel number three was “Okinawans ready for action. Washington and Tokyo decide to sweep under the problem of daily violence, such as rape, murder, noise pollution, shrapnel, by switching one base for another, and Okinawans say no.” While Alexis suggested a portrait, I decided against this, because I had already illustrated the faces of the people in the first image of the series. So in this one I wanted to highlight the powerful signage and verbiage of the protest and the fury that words can convey. The main signage in the center, this is a sign pulled from more recent protesting, but the text around it from the top left corner says “don’t become brutal” is like a rough translation of it. And this is referring to the brutality of the military base and like the history that the base has done, as this one came from, I believe, the 1995 protest. The one in the top translates to “life is the treasure”, roughly. This one Alexis can talk more about as she knows the importance of this phrase to the people.

Alexis Dudden

It’s pretty much the most important expression that Okinawans say to one another, because of the violence of the 20th century. “Life is the treasure.” It’s just something that conveys the meaning of the trauma collectively endured.

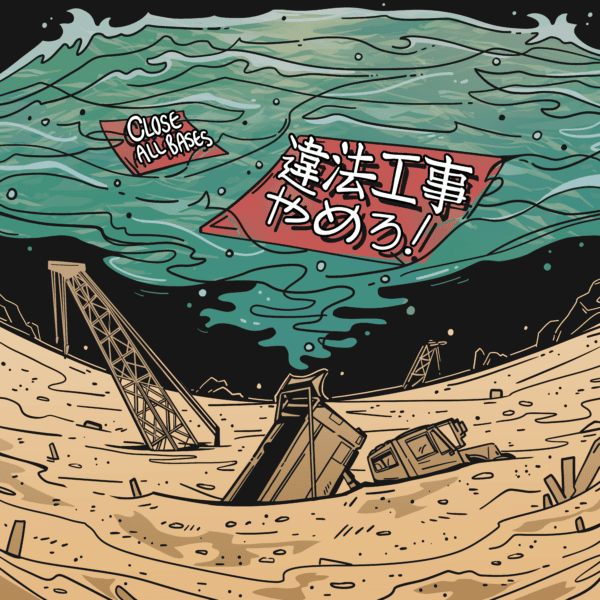

Kim Inthavong

And then the central sign, its text is fairly straightforward: “Stop illegal construction.” In the image, I decided to include the picture of the Henoko base that I drew from the previous picture. This one is in black and white. And I think just having that contrast between that and the bright red center sign with the blue in the background pulling back in the sea and how it’s important to the people.

Alexis Dudden

The way you’ve ended with that, because again, even the way that Okinawans refer to themselves is “people of the ocean,” essentially is a rough translation. So I was really impressed. And I can’t draw a straight line, so I really tried to not tell Kim how to draw. But we went back and forth, and each time I gave some notes she came back more powerful than I thought I could even imagine. And her understanding, simply by thinking through what was at the center of this, remains really impressive to me.

Daniel Story

Panel four?

Kim Inthavong

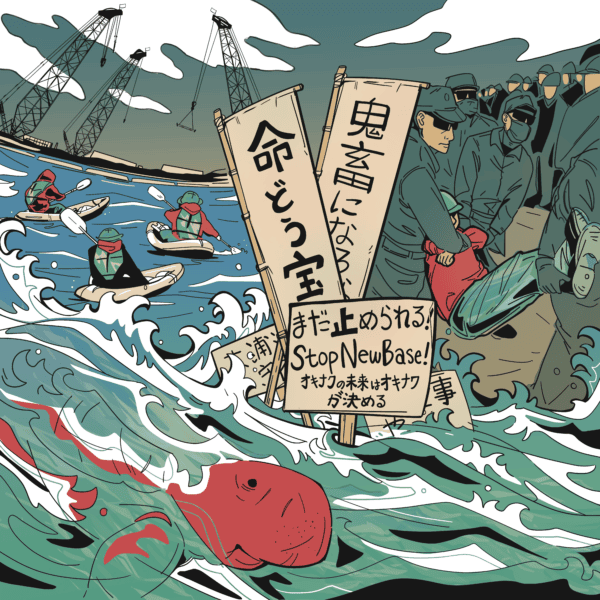

Panel four. So the topic sentence wasn’t much of a sentence. It was a theme: “The struggle. Maybe your biggest, boldest image.” She gave three topics: dugong, kayaks, and riot cops. I focused more on abstract storytelling using individual scenes of kayak protesters and confrontations with riot police. On the bottom, I illustrated a dugong in the sea. Dugong are one of the endangered species native to the region and are threatened by the base construction. I chose to color the dugong red to tie it in with the protesters fighting on its behalf and to contrast it from the cool color of the ocean waves. Alexis can touch a little bit more on the importance of the dugong as she was the one to help me realize the scope of destruction this base was having.

Alexis Dudden

The dugong is a cousin of a manatee. It’s this formerly beautiful sea mammal, like an elephant in the ocean without a trunk, and it needs a very rare eelgrass ecosystem. Construction has already devastated this system. Unfortunately, it’s possible that the dugong has already been made extinct by this stage of the construction. I was actually trying to confirm that before we spoke today, but divers haven’t seen one for a while. Oura Bay was already a World Wildlife Fund site because of the rarity of the dugong. So if there is a symbol for “the life is the treasure” that is already lost, it’s this mammal. And that’s to me one of the interesting things about the activists involved is the complexity with which they have from the beginning used the word life. It’s not simply humans against tanks, it’s all forms of life living in Okinawa together versus further violence against their existence. And I was also really grateful that Kim put in the riot cops, because this is something that’s really not been well understood outside of Okinawa, is we’re really talking about octogenarian activists who chain themselves to US military bases and then get arrested and sometimes beaten up by the local riot cops. So this isn’t just happy citizens with guitars. It has moments of real violence. One of the more interesting forms of protest too has been the sea kayakers that go out and then they get chased by rather powerful motorized boats. And they’re really responsible in how they allow other protesters—you have to take a swim test, you have to actually know how to operate your craft—because they know they’re gonna get chased by either US military boats or Japanese police boats. And so on the one hand, probably the most gentle sea creature has been made to be extinct already, or is almost, versus well within the Japanese context, overt violence is very rare. And so when the protesters get roughed up in Okinawa, it needs to be better understood.

Daniel Story

Anything more came about this panel?

Kim Inthavong

The last thing I would like to describe is the reason why I have the center signs in the picture. The signs in the ocean represent the resilience of the people. As waves crash up against them, threatening to pull them under, the signs refuse to sink. I centered the signs to highlight the mission of the protesters, surrounding the signs with the key imagery that Alexis just described, such as the protesters and kayaks, the riot cops, and the dugong.

Daniel Story

And the final panel.

Kim Inthavong

So the final panel, the topic sentence for the final panel was: “Now construction is stalled because the sediment in the bay is like mayonnaise, even as Japan’s Ministry of Defense declares.” So in this picture, I think the description “the sediment in the bay is like mayonnaise” really stood out to me, as I think it’s a very unique way to describe sand. So in this piece, I wanted to highlight that by illustrating the construction equipment sinking into its depths, really representing just the state of the base and its construction and the consequences of building it up on this foundation.

Daniel Story

So this is the sea floor we’re looking at?

Kim Inthavong

Yes, this is the sea floor that we’re looking at with the construction equipment sinking into it. But to contrast that, above the sea floor, I illustrate the top of the sea. The protesters’ messages continue to ride the waves above. The words persist as they carry the motion, advocacy, and passion of the people. So in this final image, I still bring back that important blue color, turquoise color, that we’ve been discussing throughout the entire illustration process. And then bringing back, I think, the words of the people is how even though they constantly face opposition, adversity, they continue to strive to fight for their land, their people, even for the wildlife, to their homes. They’re here to stay and their words will persist.

Alexis Dudden

I was blown away when Kim shared the line drawings, because they are so beautifully rendered. Then she shared the colors. And I have to say, since I have participated in some of the Henoko movement for about twenty years, she’s really changing the conversation with how she’s using color. Because I won’t say that it’s gotten stale, but it’s relying on tropes that are already out there. And so when there’s this red dugong and blue people—you’re doing something so new. And I’m really impressed and I look forward to sharing it with my colleagues in Okinawa.

Kim Inthavong

Thank you. And I would not [have] been able to envision this all without your support and help, this understanding [of] this topic that I had very little prior knowledge in until you approached me told me about it. And I was like, Oh, this is all happening right now. It really helped me understand and appreciate more of the work that historians are doing. So thank you for all that, for sure.

Alexis Dudden reading

What do you tell the dead when you lose? The question remains primary not only in Japan, but in all nations confronting social division today over what could be described as the politics of loss. I think of Germany, Russia, China, the United States, and so on. To this end, efforts amongst some Japanese to refashion the horrors that took place in Okinawa in 1945 into stark binaries of, on the one hand, invading enemy (the United States) versus defending forces (Japan) continue to feed a version of Japan’s 20th century that persists in erasing atrocities the Japanese troops committed throughout territories under its command. Okinawan efforts to secure their place in recounting Japan’s defeat undermines this approach. The islands’ homeland dirt demonstrates its falsehoods and deepens understanding that Okinawa territory itself is monument to a shared past. The Cave Diggers and the Society for the Protection of Life are but two recent efforts in Okinawa that make clear to other Japanese that Okinawans are equally part of the nation. Their elected officials give broader voice to their actions nationally and internationally, and the collective reliance on soil and water to do so makes clear that Okinawa and territory is monument to the present.

Alexis Dudden

There’s something about the soil itself that keeps telling the story of the past and the present. And now, this sort of unnecessary devastation of a far deeper history, this ecosystem. Trying to bring together environmental and lived histories made me think about the actual land as a monument.

Daniel Story

That was historian Alexis Dudden and graphic artist Kim Inthavong on their AHR piece, “Okinawa: Territory as Monument,” which appears in the History Lab section of the September issue of the AHR. The music you heard throughout this episode was composed by Shintaro Haioka for the soundtrack of the documentary film Zan which explores the endangered existence of the dugong in Oura Bay and the activists who are fighting to protect them. You can learn more about the documentary at zanthemovie.com and more about Shintaro Haioka’s work at haioka.jp. History in Focus is a production of the American Historical Review, in partnership with the American Historical Association, and the University Library at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Episode 6 was produced by me, Daniel Story, with engineering assistance and transcription support from Myles Rider-Alexis. You can learn more about this and other episodes at americanhistoricalreview.org. That’s it for now. See you next time.

Show Notes

In this Episode

Alexis Dudden (Professor of History at the University of Connecticut)

Kim Inthavong (software developer, freelance illustrator)

Daniel Story (Host and Producer, Digital Scholarship Librarian at UC Santa Cruz)

Music

Music in this episode was composed by Shintaro Haioka for the soundtrack of Zan, a 2017 documentary film that explores the endangered existence of the dugong in Oura Bay and the activists fighting to protect them. Music used with permission.

Production

Produced by Daniel Story

Audio engineering and transcription assistance by Myles Rider-Alexis

Panel 1

Panel 2

Panel 3

Panel 4

Panel 5