Very few things both excite and frustrate my students like food. Their faces light up when they talk about it, even as they complain about rumbling stomachs and ruined appetites. I find myself turning to food history, and particularly digital food history, as the academic year draws to a close and my classes begin their year-end reviews. An excellent way to combine economic, cultural, and social histories in an engaging way, food history shines during review. Teachers know that mixing up pedagogical and content-based approaches is key to keeping students attentive toward the end of the year as they prepare for the AP US History test or final exams. This year, utilizing a variety of digital projects, I centered one of my review days on food and food history.

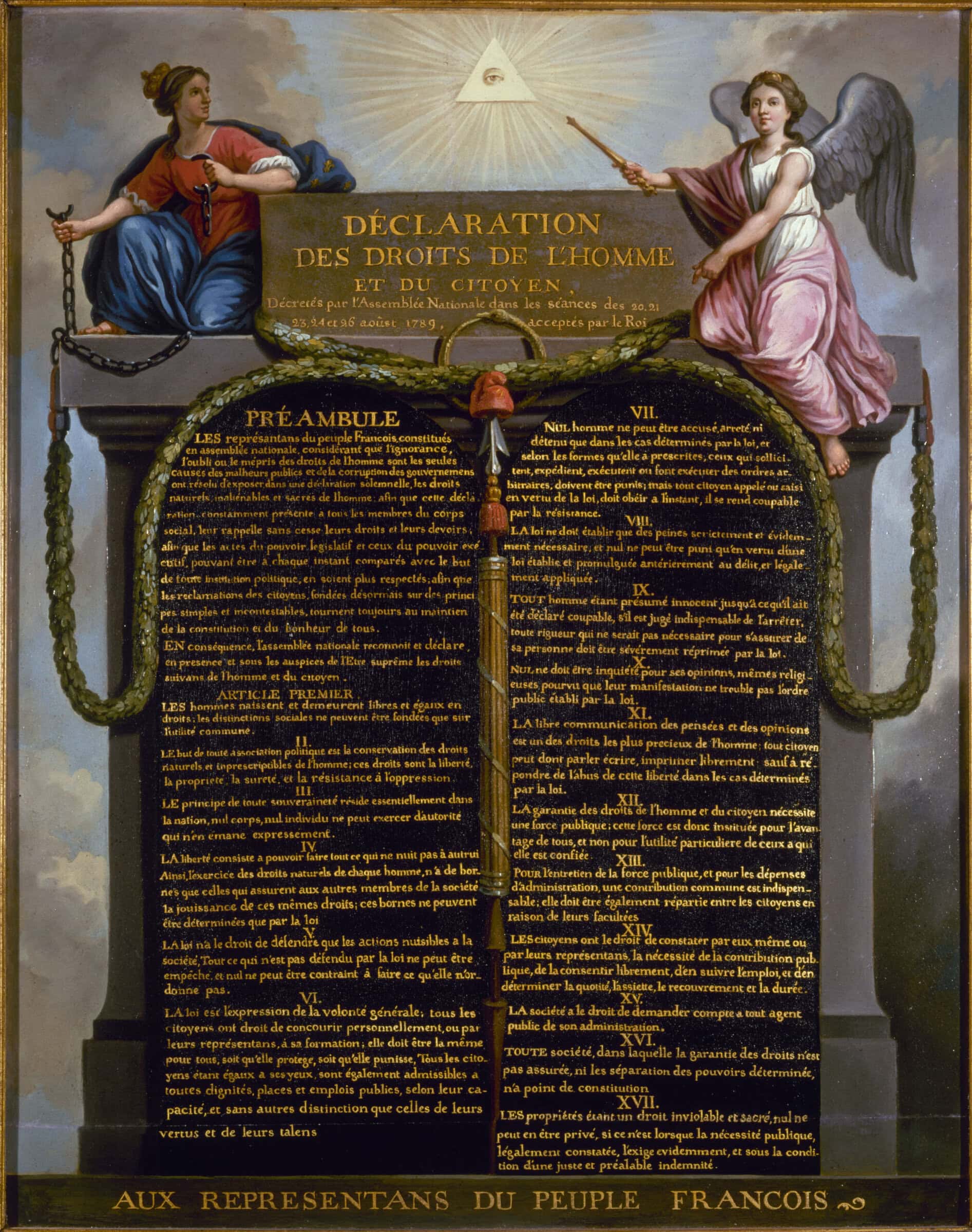

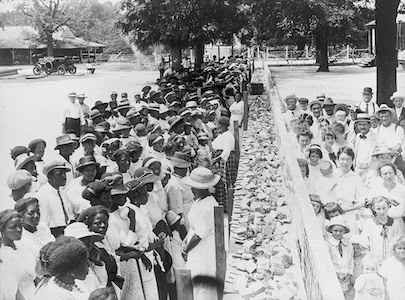

Segregated crowds attend a barbecue at an Alabama plantation. Credit: America Eats/Library of Congress

While there are a number of digital projects focusing on food history, for my year-end review I selected those that examine menus and recipes. For my first in-class activity, I turned to the New York Public Library’s landmark What’s on the Menu?, a digital archive of over 17,000 menus from more than 150 years of international dining. I printed off menus from the same hotel from three different historical eras: the close of the Civil War, the Gilded Age, and the turn of the century. I asked students to work in groups of four to perform close reading of the three menus and to discuss the differences between them. I asked them to consider how prices, the availability of foodstuffs, and even items’ names had changed. I also asked them to think about how the relative abundance of food (represented through the varieties of clams, for example) during the Gilded Age and the turn of the century contrasted with the close of the Civil War, and what that revealed about the Second Industrial Revolution, changes in supply chains, and American imperialism.

For the second activity, I used The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book, a collection of Creole recipes first compiled by the New Orleans Picayune in 1901, and Michigan State’s What America Ate, an online archive of Depression-era recipes, photographs, and advertising. I found both sources through Elizabeth Hopwood’s exceptional syllabus, Digital History: Foodways and the Forking of History. These two sources provide intriguing windows into early 20th-century conceptions of race, class, memory, and cuisine. For the purposes of review, I took a targeted approach that focused on supporting documents and some of the recipes contained within. Both sources include a variety of high and low brow recipes ranging from “rice soup” to “Tomato Consommè.” I asked students to look at the introductions, the recipes, and to explore how both reinforced and reconceived racialized conceptions of food, class, and historical memory.

For example, The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book opens with a eulogy for the enslaved cooks of the past—“the faithful old negro cooks”—who “felt it a pride and an honor, even in poverty, to cling to the fortunes of their former masters and mistresses.” But as they disappear “from our kitchens,” the eulogy continues, “their places will not be supplied, for in New Orleans, as in other cities of the South, there is ‘a new colored woman’ as well as a new white.” What do these words say about the “New South,” the early stirrings of the Great Migration, and the ways that the ideology of the “Lost Cause” stretched beyond politics and economics to something as seemingly prosaic as food?

Similar nostalgia floats through discussions of “Old West” cooking in the America Eats section of What America Ate. As the website explains, America Eats “was a Depression-era jobs creations program that sent writers and photographers across the country to chronicle American eating by region.” The project included accounts of cowboys, chuckwagons, and cookouts, but as in The Picayune Creole Cookbook, pushed aside the presence of people of color. And when it came to Native and Mexican cuisines, the project provided no more than a cursory, backward-looking glance. I asked my students to think about what this 1930s project, that started 40 years after the “close of the frontier,” said about food and cultural memory, and to also juxtapose it with the Picayune’s culinary “Lost Cause.”

Both of these projects took the entire class period, so for added enrichment I assigned another activity as homework. Most of my students have, at some point, taken a picture of a dish at a restaurant and then shared it on social media. I asked them to find one of these pictures (or any picture of food, in case they didn’t have one), and to write a paragraph that connected their dish to a historical concept or figure we’d studied during the year. Low-hanging fruit include plenty of farmers’ breakfasts (Nathaniel Bacon), a bottle of Jim Beam (Whiskey Rebellion), or sausage (The Jungle/Progressive Movement). Yet, unsurprisingly many students turned in assignments that were cleverer: one student’s interpretation of Roanoke involved a picture of a salad with a crouton (CROATON), and another connected the failure of pork rinds to catch on at our school with the failure of the Bay of Pigs. Regardless of the activity, whether it drew from Instagram or What’s on the Menu?, students found food a valuable way to contextualize and deepen their reviews.

Over the past few years, both high school and undergraduate courses have incorporated food history through a variety of digital projects. Julia Gossard’s excellent entry in the Teaching w/#DigHist series, “Food in the West,” lays out a detailed approach to teaching history by creating a “food timeline.” At the College of Wooster, undergraduates created a digital walking tour of Wooster’s culinary history using the historical tour guide app, Clio. Via the Culinaria project, students at the University of Toronto Scarborough created a variety of digital exhibits to better understand the culinary, cultural, and diasporic diversity of Scarborough and the greater Toronto area. Elizabeth Hopwood’s previously mentioned course on foodways contains a number of excellent assignments ranging from a historic cooking project to a food-based “unessay.”

At my school, teachers usually bring for students a breakfast before or lunch after their final exam. In the past, I have laid out a spread of bagels and bananas from Costco. I hoped to label them this year with brief reminders of each dish’s history (ethnic enclaves, American imperialism, for example). Unfortunately, life got in the way and instead my students got frozen treats afterward. While I don’t think that popsicles or Klondike bars showed up on their exam, I do hope my foray into food history pushed my students to think about the stories behind the food they eat, and will continue to do so long after the exam and long after they graduate.

John Rosinbum is a high school and college instructor in Tucson, Arizona. He focuses on pedagogy, research methods, and immigration history. He writes on teaching in the Teaching with #DigHist series for Perspectives Daily, and on refugee policy for the journal Refuge.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.