In spring 2019, a group of students majoring in different fields—history, theater, and immersive technology—at Shenandoah University came together with a faculty collaborative to explore how virtual reality (VR) technology might aid the study of history. The power to be present virtually for events that could otherwise be known only through research, reading, and writing proved so compelling that the working group committed itself to developing a major VR experience. The resulting project, which used well-documented debates from the Constitutional Convention, has involved more than 100 students during five years of development. From the start, our project confronted one of the mythic narratives of the founding: that the Constitution was a miracle borne of genius rather than an imperfect document hashed out by ordinary men. As the project proceeded, it demonstrated the value of virtual learning for undergraduate education broadly and the study of history specifically.

Motion capture was used to animate the convention delegates. Lee Graff, Shenandoah University

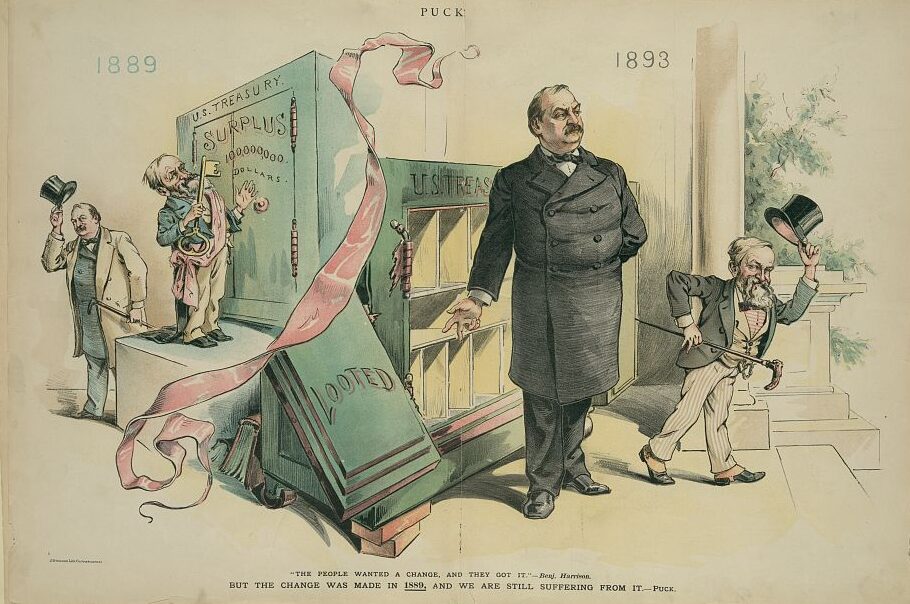

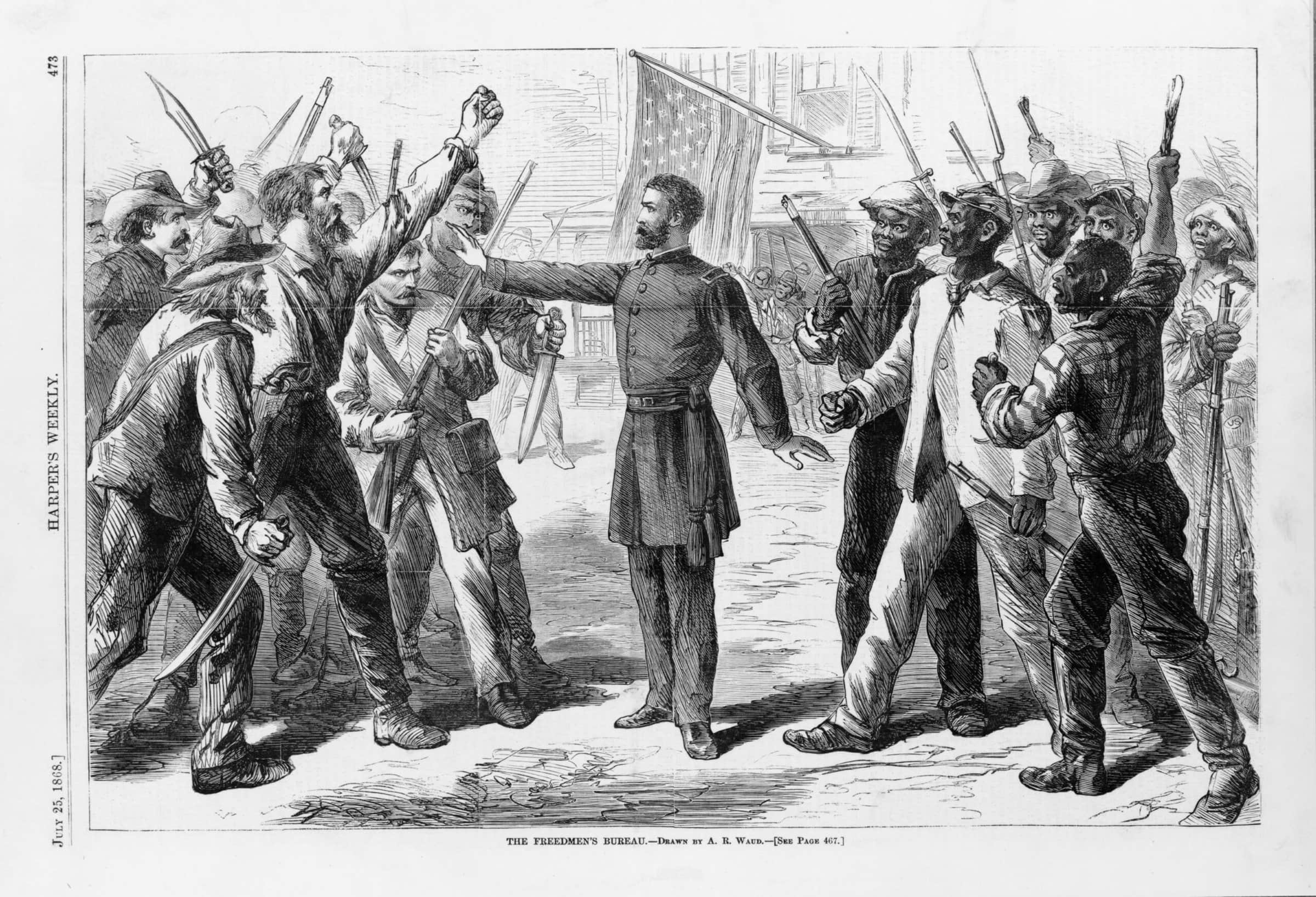

Whether the Constitution of 1787 was a work of political genius—of a convention of geniuses—is a question that has long preoccupied historians. In a July 2, 2024, op-ed in the Washington Post, Gordon Wood asked, “How did Revolutionary America produce so many geniuses?” Clearly, delegates to the convention possessed significant political talent. Schooled in the rough and tumble of revolutionary-era America—waging war against Great Britain, participating in the political arenas of state and confederation governments—they also represented the interests of property and social class, and many of them were enslavers. They attained the heights of the convention on well-practiced rhetorical abilities of reasoning collectively from hard-wrought experience and abstract philosophy. They gathered in Philadelphia to address a crisis of postrevolutionary governance that included widespread civil unrest, economic collapse, divisive foreign interference, and the popular politics of paper money and debtor relief. As the Pennsylvania Gazette put it in September 1787, what resulted was a “revolution in favor of government” that closed the circle of a “revolution in favor of Liberty” opened some 11 years earlier.

Accepting the narrative of a “miracle” in Philadelphia leaves us little more to teach than the tenets of an immutable Constitution conjured up by a party of geniuses. But we live and work with a generation of students who want to discover knowledge and create new templates rather than sit together at the founders’ feet venerating a lifeless document. To that end, it makes more sense to reframe the question of political genius at the Constitutional Convention as one of ingenuity—a gathering of practical people bringing experience and ideas to bear on the problems of a dysfunctional confederacy and the challenge of creating a republican nation state. They rose to the occasion as ordinary people, albeit privileged and self-interested, responding to extraordinary circumstances. Teaching the Constitution this way can become a process through which students learn how the founders thought, debated problems, and reconciled differences to create not the most perfect government their genius could devise, but the best government that people with a say in the matter would accept.

The delegates perceived the problem of how to select the new republic’s chief executive as one of their greatest challenges. “This subject has greatly divided the House,” Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson observed. “It is in truth the most difficult of all on which we have had to decide.” With this “most difficult” question in mind, our students and faculty came together around the novel technology of virtual reality and the emerging field of immersive history, which has the power not only to put people “in the room where it happened”—as Aaron Burr croons in the musical Hamilton—but to ask what people would learn by being in the room when it happened. The room, of course, is the Assembly Room of the historic Pennsylvania Statehouse in Philadelphia (now known as Independence Hall), where the Declaration of Independence was signed and the Constitution drafted. Notes taken by James Madison and other delegates provide an authentic script.

Our students and faculty came together around the novel technology of virtual reality and the emerging field of immersive history.

In the field of immersive technology, “presence” is a term of art describing the effect of being transported virtually to a different time and place. In our case, this cognitive leap immersed us in the Assembly Room in summer 1787. Granted, in some sense all media are immersive. While reading, we imagine people and places of the past, picturing them in our mind’s eye. That picture, however, remains an abstract representation of history, and we are merely observers. Documentary film is another medium that engages our senses with sound, sight, and emotion. Yet the subject–object differentiation persists, as it does with online digital media. All this is not to argue that immersive media are superior to text, film, or digital history. The power of text to convey ideas and evidence remains unquestioned. Virtual reality, however, is different, and it is the phenomenon of presence that distinguishes it. We read a book, watch a movie, visit a website. But we experience virtual reality, and we remember best our most vivid experiences. From the immensity of historical fact, what we readily recall are often our visits to historic sites—the places where “it” happened. A smell, the sound of a bell, the tick of a clock, an angle of light through a window can all trigger recollections and stimulate powerful emotions. Suppose we recreate these memory cues in virtual experiences by being present within them. What could we learn?

In the spring of 2019, we set forth to find out. Our efforts combined technical, academic, and educational objectives. With teams of students and staff developers, Mohammad Obeid oversaw the creation of a vivid, virtual replica—a digital twin—of the Assembly Room, the construction of delegate avatars, their animation and vocalization, and the programming necessary for the virtual representation of their debates. In the process, students learned the art of virtual reality design and the technology of building virtual experiences, while Warren Hofstra and Kevin Hardwick instructed them in methods of research and documentation and pursued the question of immersive technology’s ability to produce unique forms of knowledge.

Taking our cue from the nation’s first chief executive, we’ve titled the result of these efforts The Great Experiment. In January 1790, George Washington wrote the English historian Catharine Macaulay Graham: “The establishment of our new Government seemed to be the last great experiment, for promoting human happiness, by reasonable compact, in civil Society.” Washington’s comment serves as a dual reference—to the Constitution itself and to our own experiment of casting its creation in virtual reality.

The Great Experiment is a five-level, multiplayer immersive experience. (Watch the documentary video to see what it looks like.) Participants begin in the Assembly Room, witnessing an 18-minute segment of the debates that took place on June 1–2 and July 17–19 on choosing the chief executive. During these debates, the essential arguments for selection by the national legislature, state legislatures, governors, or the people were aired, debated, and eventually rejected in favor of a system of electors. The VR experience becomes progressively more immersive and interactive. Up to nine participants can experience a personal session with one of the delegates. They carry the insights about personal principles and political positions into a reenactment of the debate, first in the guise of their delegate avatar and the exact words of Madison’s notes, and then in their own words. In a final level, participants engage in an open debate, bringing everything they’ve learned to bear on an original constitutional question. In test runs, students have debated how to replace the Electoral College with an institution more sensitive to the will of the people today.

These debates fulfill a civic purpose, demonstrating in our age of divisive partisanship that the Constitution emerged from deliberation among individuals convinced that reasoning together in “free argument and debate” could produce consensus. In The Great Experiment, participants not only observe and read debates; while present in the Assembly Room and virtually among other delegates, they also debate ideas in their own words and then apply them to contemporary issues. The mild stress of speaking before others intensifies memories, promotes learning, and becomes a powerful instrument of persuasion. Rising above themselves, students gain a better understanding of the impact that ideas exerted in the Age of Revolutions.

In The Great Experiment, participants not only observe and read debates; they also debate ideas in their own words and then apply them to contemporary issues.

Returning to our original question of political genius: If we regard the Constitution as a work of craft instead of spontaneous brilliance, our students can learn that craft—much like 18th-century apprentices—by experiencing it. If the delegates rose to an occasion of crisis, reasoned together, and resolved issue after issue to devise a Constitution that continues to guide the “last great experiment, for promoting human happiness,” then perhaps we can teach the Constitution by putting our students in a virtual replica of the convention, allowing reasoned deliberation to be experienced, learned, and put to use. Art and artifice can be joined in a new reality.

The Great Experience will launch at Shenandoah University on September 27, 2024, as a product of the Shenandoah Center for Immersive Learning, the Virtual Reality Design program, and the history department. For more information, after September 27 visit su.edu/tge or contact Warren Hofstra at whofstra@su.edu.

Warren Hofstra is Stewart Bell Professor of History at Shenandoah University and Kevin Hardwick is professor of history at James Madison University; they are collaborating on a companion volume, “‘Perfectly Novel’: The Intellectual Origins of the Electoral College.” JJ Ruscella is founder and executive vice president of AccessVR. Mohammad Obeid is associate professor and director of the virtual reality design BS program at Shenandoah University and co-director of the Shenandoah Center for Immersive Learning.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.