Teaching the history of the Reconstruction era in the current moment is as challenging as it is exciting. With states restricting the teaching of AP African American Studies courses and curtailing the types of lessons that children learn in K–12 schools, especially when it comes to the histories of race and slavery in the United States, I find that when students come to college, they are ready to have their assumptions upended. They are often eager to learn about histories that, recently, lawmakers have labeled “too contentious” or “un-American.”

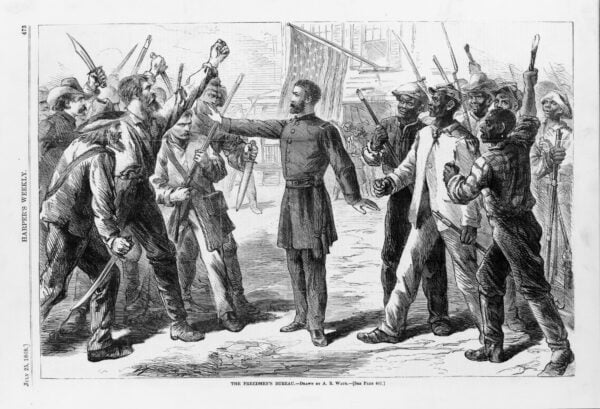

In this 1868 Harper’s Weekly engraving, Alfred R. Waud depicted a man representing the Freedmen’s Bureau standing between armed groups of white and Black Americans. Library of Congress/public domain

In the past, I have taught American Slavery and American Slavery and the Law as undergraduate courses. In the lecture course American Slavery, I guide students through American history using slavery and systems of enslavement as the main analytical lens. From the Atlantic slave trade and the American Revolution to the Louisiana Purchase and the Compromise of 1850, I trace major events and themes in American history to 1877 through the history of slavery. Similarly, I have taught American Slavery and the Law as an introductory seminar. In welcoming 15 nonmajors (though majors like to sneak in when they can) into my course, I tell them that they will be learning how to read and understand important laws of slavery that emerged from the 17th to the 19th centuries. One of the most important, and fun, parts of both courses are the lessons on Reconstruction and, specifically, the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution.

I find that if students do understand 19th-century American history, perhaps through an AP US History course, it is isolated to the Civil War. But when I teach courses focused on 19th-century America, I often pose a specific set of questions to help prime students for discussion and lecture. What happened when slavery ended? As historians, when do we mark slavery’s end? How close did the nation come to fulfilling enslaved peoples’ and abolitionists’ goals of creating an interracial democracy?

It is easy to believe that once Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, enshrined in the words, “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free,” that Lincoln, supported by his war cabinet, had legally abolished slavery. Most students come into my class understanding, in the broadest terms, the importance of the Proclamation in shifting the momentum of the Civil War and providing a pathway for enslaved peoples’ legal emancipation. But enslaved people, free Blacks, and even Lincoln and members of his administration recognized ensuring the legal end of slavery in the United States required further action—a point I emphasize to my students. And it is in these lessons that I integrate the legal history of slavery, which includes leading students through a deep and textual analysis of the Reconstruction Amendments.

As historians, when do we mark slavery’s end?

I strive to convey that the Constitution and its amendments need to be grappled with and examined, and I encourage students to critique the document itself. Our in-class examinations include exploring the varying perspectives that come to bear on understanding the Constitution, which involves studying the political, economic, and social milieu. Moreover, to fully comprehend what the amendments mean, as historians, we must consider the historical context in which they were created and ratified.

For example, in the final week of my American Slavery course, I discuss the history of Reconstruction. I examine the excitement among freed people over Special Field Order No. 15, the creation of the Freedman’s Bureau, and the promise of the Freedman’s Bank. I also focus on the major legislative triumphs that both African Americans and their white Republican allies won during this period, with the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments taking center stage.

I urge students to parse the language of the 13th Amendment and to grapple with the historical implications of slavery’s legal end. It reads: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Then I preface my discussion and my questions by recognizing an important aspect of this moment in American history. Yes, Congress passed a law that legally abolished slavery. And, yes, it is true that to study the end of the Civil War and the era of Reconstruction, it is important to examine and celebrate the real triumph that the amendment was for the millions of freed people and African Americans more broadly.

But importantly, we must focus on the amendment’s limits. As scholars Michelle Alexander and Douglas Blackmon have argued, the amendment’s language leaves open a question that I encourage my students to interrogate. How might we consider the clause “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted”? I nudge students to consider what this clause might allow for, how an institution that was not slavery, but perhaps had historical linkages to systems of enslavement, might have been enshrined in the amendment—and in this clause. Might the 13th Amendment have paved the way for other exploitative labor arrangements that affected the lives of African Americans or perhaps the descendants of formerly enslaved people into the late 19th and 20th centuries? We discuss the amendment’s connection to the rise of convict leasing in the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and to the expansion of the prison industrial complex in the 20th and 21st centuries.

I ask similar questions when I introduce the 14th Amendment, which addressed birthright citizenship, due process, citizens’ “equal protection of the laws,” the repayment of Confederate debt, and prevented anyone who participated in “insurrection or rebellion” against the United States from holding a political office. Historians have argued that this amendment, perhaps more than the 13th and 15th Amendments, fundamentally altered the ways in which citizens engaged with the federal government. Scholars such as Martha Jones and Kate Masur, excerpts of whose books I have assigned in my courses, have offered incisive interrogations of the 14th Amendment’s history. I then remind students of the conversations that we have had about the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857, which rendered enslaved people, and people of African descent more broadly, as noncitizens of the United States and reinforce the fact that the 14th Amendment overturned the Dred Scott decision.

The 14th Amendment is perhaps the most powerful—and some might contend, the most dynamic—of the Reconstruction Amendments.

I also propose the argument, made by legal historians, that the 14th Amendment is perhaps the most powerful—and some might contend, the most dynamic—of the Reconstruction Amendments. It encompassed a range of privileges. For example, the clause that enumerated birthright citizenship is considered by scholars to be one of the most important of the amendments. Civil rights activists, especially in the first half of the 20th century, used this legal idea to fight for citizenship rights. But it also contained a set of restrictions that are important for students to understand. While people of African descent gained citizenship rights, the amendment excluded Chinese immigrants, who did not gain the right to become naturalized citizens until 1943. In emphasizing the enduring importance of these amendments, I hope that students will gain a better appreciation for the historical moment in which they were created and ratified.

I then end my discussion of the Reconstruction Amendments with the 15th Amendment, which extended voting rights to African American men. “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” it read. Shortly after the amendment went into effect, Black men began voting in droves, sending the first African Americans to Congress. My students learn about Black politicians such as Senator Hiram Revels of Mississippi and Congressman Joseph H. Rainey of South Carolina. While celebrating these achievements, I convey that the 15th Amendment was just the beginning of African Americans’ continued fight to exercise and protect their voting rights. I bring into the discussion an 1876 case, United States v. Reese, the first voting rights case decided by the Supreme Court after the 15th Amendment’s ratification. In an 8–1 decision, the court ruled that the 15th Amendment “does not confer the right of suffrage, but it invests citizens of the United States with the right of exemption from discrimination in the exercise of the elective franchise on account of their race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” I often encourage students to spend some time doing a textual analysis. With their reading of this case, students have often concluded that this case undermined the 15th Amendment and paved the way for voter discrimination. If I have time—and continue to have their attention—we discuss voter suppression strategies such as poll taxes and literacy tests, which proliferated in the Jim Crow era.

I have made it a habit to teach the students who enroll in my courses how to read and understand the Constitution, especially when it comes to the history of race and slavery. And for many of my students, my classes provide them with one of their first opportunities to critically engage with the Constitution in concrete ways. For this reason, I make examining the Reconstruction Amendments a central component of my courses on African American history and the history of American slavery. Ending these courses with Reconstruction and the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments offers students an enduring lesson in how historians think about the law. I also hope that they gain a fuller appreciation for this history not simply as students, but as global citizens.

Justene Hill Edwards is associate professor of history at the University of Virginia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.