Danton, Robespierre, Marat, the Abbé de Sièyes, Etta Palm, and other French revolutionaries were discussing the ratification of a new constitution, one that would establish a progressive, representative government. But, on the last day of debate and voting in the National Assembly, things went sideways for the Jacobins, who had been in control of the body to that point. Suddenly, King Louis XVI, who had earlier fled, returned to Paris with an Austro-Prussian-Swedish Army, accompanied by Catherine of Russia. Together they retook Paris and reinstated absolutism. The Jacobins, despite getting nearly all their articles ratified, were defeated, imprisoned, and many guillotined.

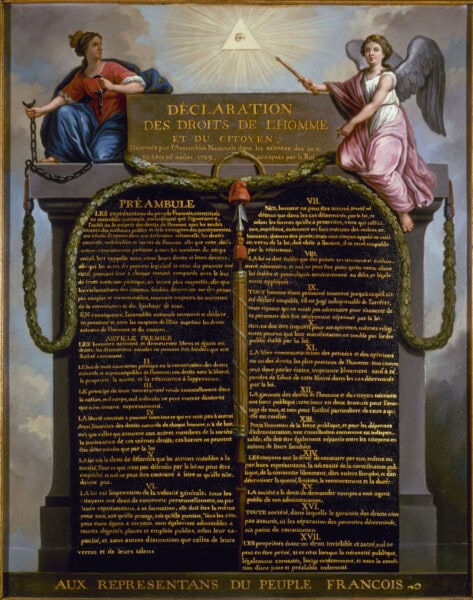

Putting students in the shoes of revolutionaries and drafters of constitutions produces a different kind of engagement. Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier, Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen (1789), Paris Musées, public domain.

This chaotic end to the French Revolution likely sounds odd to you. That’s because it took place not in 1791 but in 2023, during the final game session of Rousseau, Burke, and Revolution in France, the Reacting to the Past (RTTP) simulation. On Zoom, posed in front of virtual backgrounds depicting revolutionary Paris, 20 students spent five weeks in historical character creating France’s first constitution, vociferously debating amendments, writing incendiary newspaper pamphlets, and negotiating to get their faction’s ideas included in the governing document. Right as we were signing off Zoom, the student playing Louis XVI shared that he asked ChatGPT for assistance in writing to various European monarchs for support, thus why Catherine the Great showed up. He remarked excitedly, “But even ChatGPT couldn’t have written an ending this fabulous for me!”

This was the first time a student openly admitted to me that they had used ChatGPT. I had no established policy against its use, and considering the way he used it, I did not find it to be an academic integrity violation. I knew the student’s thoughts were his own, since by the very nature of the RTTP pedagogy, I could assess his engagement with material and his development of critical thinking skills in multiple ways. But his admission did explain the bizarre arrival of the Russian empress who, though no fan of the French Revolution, never sent troops westward.

This moment crystalized the importance of employing different pedagogical strategies such as Reacting to the Past to teach constitutionalism to 21st-century students. This method allows instructors to assess students’ progress on relevant learning objectives in multiple ways in a time when essays may be easily generated for students. Simultaneously, this student’s admission encouraged me to think about how I could teach with and around generative artificial intelligence (AI) programs like ChatGPT to further teach constitutionalism.

It becomes glaringly obvious to instructors and students alike who has not completed the reading and preparatory materials.

RTTP is a series of historical role-playing games in which students adopt the identities of historical figures. Students engage in debates, negotiations, and decision-making processes all in-character. Meticulously researched, these simulations place students in historical moments of controversy and intellectual ferment. Rooted in pedagogical game theory and immersive learning, RTTP games seek to combat classroom passivity by leveraging the motivational power of play. With the instructor serving as a guide called the “gamemaster,” students make their own decisions and must be active learners. Each game focuses on seven key learning outcomes and transferable skills: primary source analysis, critical thinking, writing, speaking, leadership, teamwork and problem-solving, and world citizenship—all skills that help students engage as 21st-century citizen-scholars.

I use both the American Revolution simulation, Patriots, Loyalists, and Revolution in New York City, 1775–1776, and the French Revolution simulation, Rousseau, Burke, and Revolution in France, in my honors course on the Age of Revolutions. Each semester, the 20 to 25 students in the course usually fit very well with the number of roles available. (Since 2020, I have taught this course synchronously online.) Much of my time in the classroom is “flipped,” with students actively applying material they learned in preparatory class sessions, through assigned readings, and in learning materials such as recorded mini lectures.

Because the game requires active participation, such preparation is essential for student success. Though students could still use AI platforms to author their essays or speeches, they would have a very difficult time defending their or their faction’s positions on a topic during in-class debate. It becomes glaringly obvious to instructors and students alike who has not completed the reading and preparatory materials. Often, students note on end-of-term evaluations that the pressure to perform for their peers is what made them complete readings that otherwise they may have skipped.

Instead of rejecting AI in my pedagogy, I’ve developed several assessments that teach with AI, which I have written about elsewhere. One assessment that I use in this course asks students to write their own constitutions in small groups. The first constitution they write is created entirely by group members’ own ingenuity. Often, students revise significant portions of the US Bill of Rights and the French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen. Many students revise language that excluded people of color, women, and those from other minoritized groups, creating more inclusive constitutions. After the small group creates their own constitutions, I require them to write a prompt (or a series of prompts) they can put into ChatGPT to write a constitution. Once they find a version of a AI-generated constitution they are happy with, the group compares it with the constitution they wrote.

This activity teaches students not only how to more efficiently prompt ChatGPT but also about its limitations. Similar to Jonathan S. Jones’s exercise of having students critique GPT-generated essays (a strategy I also employ in my courses), this assignment encourages a similar skepticism to GPT-generated writing. While almost every student remarked that the GPT-generated constitutions were well written, they also complained that many articles of the constitutions were unimaginative. One student remarked on their reflection that they had “hoped ChatGPT would whip up a document that was unique, fresh, exciting, new and young,” but the results largely replicated the US Bill of Rights and the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

Students walked away from this exercise having learned that ChatGPT was not capable of good, original creative writing. In fact, plagiarism was the biggest complaint students had regarding their AI-generated constitutions. Students reported that ChatGPT plagiarized from well-known sources including the Federalist Papers, State of the Union addresses, and even proposed constitutional amendments like the Equal Rights Amendment. Several constitutions included specific articles that dealt with stronger net neutrality, despite those groups not including these topics in their prompts. Many questioned ChatGPT’s sources and went on discovery missions to figure it out. One keen student observed that their constitution’s statement on net neutrality came directly from the Obama White House’s archives. The student remarked that it was interesting to recognize that, despite claiming to be inherently apolitical, the type of sources it used to generate responses might create politically charged statements. As one student put it, ChatGPT was “slapping words and thoughts together from sources online to answer the prompt.” This got students talking about inherent internet biases and the need to assess ChatGPT’s statements with a critical lens. This exercise, then, allowed students to demonstrate their critical and analytical thinking they had mastered around topics essential to constitutionalism.

While RTTP allows instructors to adapt assessment and students to change how they demonstrate mastery over material, it will not entirely do away with uses of generative AI in the classroom. As we navigate this next chapter of higher education, we may not want to put drastic limits around generative AI either. This past academic year, I conducted a study among USU history majors (IRB #13569) that showed 100 of 102 students surveyed admitted to using a large language model like ChatGPT or Google Bard on an assignment. The number of students, though, who said they have turned in or regularly turn in work that is entirely generated by these platforms with no additional edits in history classes was just 2 out of 100. Most students surveyed (58) reported that they used ChatGPT “more frequently than not” but with extensive editorial oversight. Students explained that meant the work they turned in was still their own but may have taken inspiration from ChatGPT’s explanation of complex topics, used its suggestions for citations, or adopted its examples.

To students, using AI may not always be about taking a shortcut.

Unless the instructor had strict policies barring total use of AI on assignments, those same students did not perceive what they were doing as an academic integrity violation. In fact, one student wrote, “I don’t see much of a difference between [using ChatGPT] and looking up a reading on Cliff Notes or Wikipedia. Those can be a gray area with cheating but generally looking up those cites [sic] to help me get background and better understand the reading are acceptable research.” To students, using AI may not always be about taking a shortcut but about better understanding their coursework or producing work they feel is of a higher caliber.

AI is here to stay, and from these experiences I’ve learned to think creatively about new ways to assess student learning, relying on methods like Reacting to the Past and in-class simulations. These technologies are being embedded into every facet of our lives, from Google searches to our email inboxes and our pets’ water bowls. We must rise to the challenge to assess student learning in ways that break with tradition while still teaching the analytical and critical thinking skills that today’s students need as 21st-century citizens.

Julia M. Gossard is associate professor of history and associate dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Utah State University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.