There’s a disconnect in our discipline. Most incoming college students think of history as a chore, a requirement to get out of the way. These students have received the false message that history is about memorizing facts and regurgitating them on exams. “History is boring,” the saying goes.

But historians know the opposite to be true. Research is thrilling. Nothing beats the jolt of adrenaline we have all felt when an aged document or interview resonates with meaning. These experiences propel our passion for research and send us searching for more—more questions, more answers, more meaning.

We wanted to share this excitement with our undergraduates, to reframe history for them through the research process—even in introductory classes. We also wanted a way to showcase historical thinking and interpretation. But how might we be able to think through sources with our students, especially in larger classes?

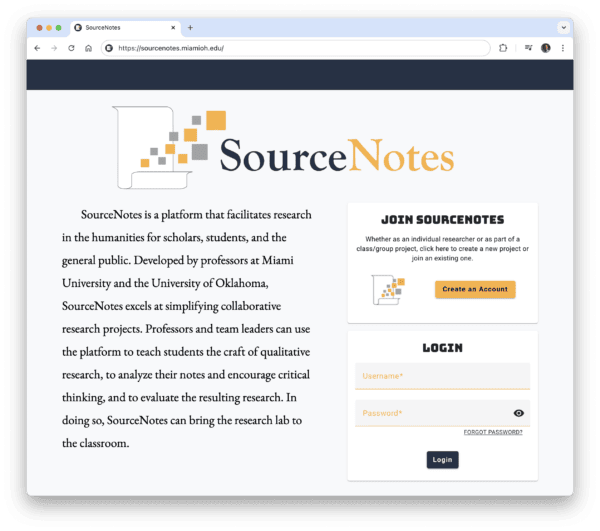

To do this we created SourceNotes, a platform that makes collaborative research in undergraduate classes feasible and, dare we say, fun. SourceNotes enables teachers to join their students in the trenches of historical research. It includes a number of features beyond notetaking: the ability to post research guidelines, to address student questions, to comment on individual notes, to bookmark exceptional notes for display, and to provide predefined sources for citing. It also offers optional features for each project: the inclusion of a “leaderboard” that ranks research productivity by notes, words, and tagged metadata; the ability to rate notes using a star-based system; and a way to provide both quantitative and qualitative feedback to each student via a gradebook.

We might lead our students to sources, but how were they to think?

The idea for SourceNotes grew from a modest impulse: to share the craft of historical research with our students. We wanted to reach students with fewer lectures. We aimed to teach through collaboration, to illustrate the importance of thinking through primary sources, asking relevant questions of them, and taking useful notes as a precursor to writing a paper.

Along the way, though, we stumbled upon a yawning gap in our previous expectations of students. We might lead our students to sources, but how were they to think? Before using the platform, we could only gesture towards “thinking like a historian,” through clunky exercises like projecting a document and discussing interpretation, bias, intent, and reception. We could strategize with our students for a potential topic, and identify available sources, but beyond that point we could only see the results upon a term paper’s submission. What of all that time spent thinking and interpreting, between encountering a source and citing it? Something was missing, and SourceNotes could help fill this gap.

In developing the platform, we prioritized intuitiveness. The system needed to be streamlined for undergraduates, who might only take a single history class, but we also wanted it to be robust enough for collaborative research, to allow instructors to view and discuss student research, quantify it, and evaluate it.

The platform differs from existing alternatives. While Zotero is fantastic for citation management, particularly for advanced graduate-level research with secondary sources, the program can present a steep learning curve for undergraduates, especially in the confines of a single semester. Zotero also lacks ways to critique others’ notes, give feedback, and learn from this process. Omeka excels at presenting research results, but SourceNotes is dedicated to the research process itself (though one can, if desired, share a project publicly with the click of a button). Dedoose is a wonderful qualitative research tool, though it can be prohibitively expensive, while SourceNotes—including pedagogical tools—is free.

We have used the platform for several years in our own teaching, and have opened it to a number of others. We now invite the broader community of historians to use the system in their own classrooms. By way of illustration, here are two examples from our classrooms that show how teaching research in an undergraduate setting has reframed the discipline of history for our students.

Researching the Spanish Borderlands

At the University of Oklahoma, Raphael has used SourceNotes in multiple classes, perhaps most successfully in a course on the history of Spanish borderlands from 1500–1900. After he trained students in historical notetaking and guided them through readings on the region’s history, each student selected a book-length primary source as their focus.

Sources included collections of primary sources like Great Cruelties Have Been Reported: The 1544 Investigation of the Coronado Expedition by Richard Flint and The US War with Mexico by Ernesto Chavez, and travelers’ accounts like Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s Narrative.

Students took notes on broad questions about Spanish imperialism and Native responses, but Raphael also instructed them to take special note when women and children appeared in the sources. With 40 students examining 40 distinct sources, the group uncovered far more about these oft-buried stories than any individual researcher could in the same short time. By focusing class discussion on students’ notecards, they could share best practices and achieve a mosaic-like understanding of the lives of women and children in the borderlands, with data points drawn from a 40-volume archive of borderlands life.

One student used passages from the Florentine Codex, a vivid account of pre-Hispanic life in the Aztec Empire, to show multiple instances in which Native people demonstrated tenderness and devotion to the welfare of their children—an unexpected finding given the centrality of warfare in the history of the Mexica. Another working on Jesuit missionary documents from northern Mexico found that Native communities treated even captive children kindly, whether they were Spanish, Native, or mixed-descent. Out of such fleeting references to the lives of children, the class as a whole brought complex worlds of Mesoamerican parenting into view.

Chinese Borderlands in the Gilded Age

At Miami University, Andrew wanted his junior-level Gilded Age America class to investigate the era of Chinese Exclusion via newspapers published in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas from 1880–1900. Students used the Library of Congress Chronicling America database of digitized newspapers to search for Chinese experiences through articles and reports, research that would later feed into their term papers. There was a problem, though: How could 30 students tackle such quantity (20 years in four states) within the confines of a single semester?

To address this, Andrew connected with two other professors—Alice Baumgartner (Univ. of Southern California) and Allyson Brantley (Univ. of La Verne)—teaching the history of the American West. Across the three classes, 80 total students could make the challenge feasible. The three teachers together divided the source-base by state, and then individually assigned a date range for each student. The research was not exhaustive, mind you. Each student was responsible for finding what they considered to be the most important Chinese-related news events of their time in these English-language sources. The result, though, was that the students collectively processed 1,155 news items, giving the entire team a large dataset searchable by full text, keyword, person, or company, and sortable by date or state. This resulted in term papers that were more nuanced, insightful, and reflective of broader experiences in the era.

Students collectively processed 1,155 news items, giving the entire team a large searchable data-set.

Three students, one from each participating class, took advantage of this depth and presented their papers at the Western History Association conference the next year: “Understanding the Human Cost of Chinese Exclusion: Arizona Territory, 1889–1891” by Carla Espinosa (Univ. of La Verne); “Opposition to the Chinese Exclusion Act in the US-Mexico Borderlands” by Jordan Fields (Univ. of Southern California); and “The Chinese Six Companies: The Chinese Economic, Political, and Community Authority in San Francisco’s Chinatown” by Liam Walker (Miami Univ.).

As Andrew’s students began their research, though, some remained skeptical. “I don’t really know some of the students in this class, much less at the other universities,” one student said. “How do I know that I can trust their research?” This student voiced a concern held by many: “If we are going to use their notes in writing our papers, how do we know these notes are reliable?” (“Welcome to the discipline!” Andrew thought.)

With students, Andrew discussed how to discern quality notes and interpretation, and how intellectualism, accuracy, and even grammar inform this assessment. Because they used Chronicling America online, consulting the original source was a click away. Encountering others’ notes therefore not only gave all students assistance in finding relevant materials, it also offered experiential learning about textual interpretation and bias. Liam Walker, mentioned above, relied on more than 27 notes taken by seven different students, with the keyword of “Chinese Six Companies.” SourceNotes organized these chronologically, which provided a tremendous boost to the early writing process.

Through SourceNotes, teachers can give students a comprehensive apprenticeship in the process of historical research. Students and faculty alike can work through daunting amounts of historical evidence collaboratively. The most motivated students quickly learn to take quality notes, a skill central to most any profession. And all participants can share the wonder of hearing new voices and making new discoveries, an experience that can change perceptions of our discipline from “boring” to thrilling.

If you are interested in using SourceNotes in your classroom and would like some guidance, please reach out to us for ideas or assistance.

Andrew Offenburger is associate professor of history at Miami University. Raphael Folsom is associate professor of history at the University of Oklahoma.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.