Ready to pivot to video on the book trail? It’s time to shelve the 10-slide PowerPoint, boost your WiFi, and think about how to sell books while building a sense of community.

Are virtual events the new fireside chat? Vojtech Bruzek/Unsplash

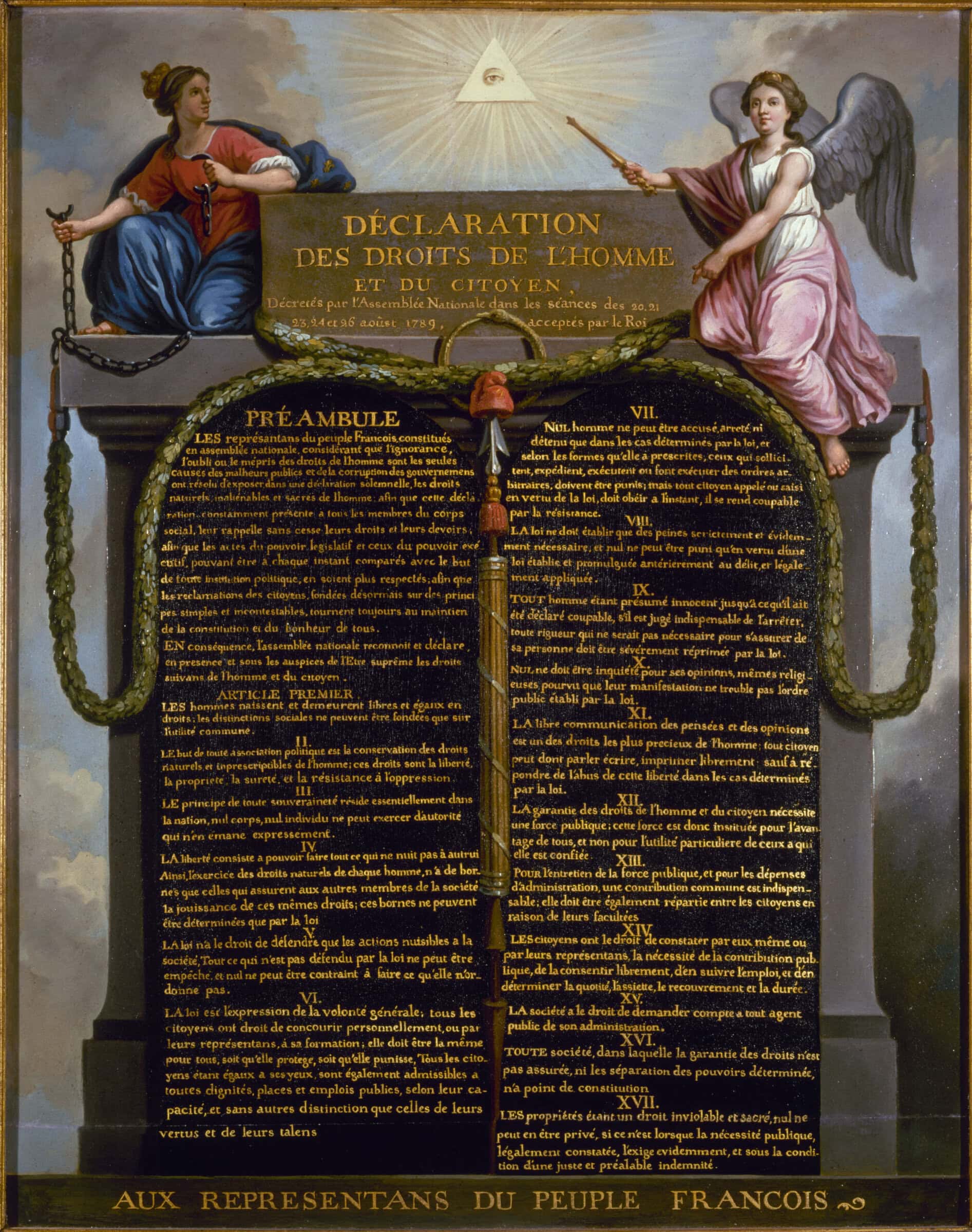

While the COVID-19 pandemic has upended and reshaped scholarly practices, new dynamic outlets for historians to engage with readers have popped up online. A typical lecture may net a crowd of 20, but platforms like Zoom can ramp up the audience ranks to the hundreds or even thousands. And with many libraries, museums, and archives closed to uphold public health guidelines, a virtual book talk can crack open the vault to access resources that we cannot currently visit in person.

So what skills do we need now to share our research? I spoke with a few of the authors and hosts who make virtual book talks happen. Their main advice: Ditch your notes, test your tech, and get ready to freestyle.

It takes a lot of work to host a livestream, but the public history community’s embrace of podcasts, social media, and digital exhibits has paved an innovative way forward. As a host, explains Jim Ambuske (George Washington’s Mount Vernon), the goal is to connect the audience with a primary text—just as we do in the classroom. Ambuske draws on his tenure at the Center for Digital History, Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington, where he hosted the podcast Conversations at the Washington Library before he began producing and moderating Washington Library Digital Book Talks. With a virtual book talk, he sends each author a detailed set of questions, meant to raise general themes for the audience to seize on in the Q&A. And, yes, it’s very live. “There is no opportunity for editing; there is no going back once the Broadcast sign flashes red,” Ambuske says.

Ditch your notes, test your tech, and get ready to freestyle.

If that sounds a little nerve-wracking, fear not. As she transformed her book tour for the virtual realm, Lindsay M. Chervinsky (Institute for Thomas Paine Studies at Iona Coll.), author of The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution, worked out a few key hacks. She pared down her own remarks to 20 to 30 minutes to reckon with screen-weary participants and to maximize the question period, and she experimented with different formats. “I think the most effective format was a conversation I hosted with Heather Cox Richardson and Harvard Book Store. We brainstormed ahead of time and came up with five or so topics, but then just freestyled the conversation from there,” Chervinsky recalls. A willingness to think on your feet is key, she adds, and it doesn’t hurt to dress up as you would for a live event—favorite shoes and all.

Megan Kate Nelson, author of The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West, agrees. She hit on her new favorite format at a recent Boston Athenaeum presentation: talk extemporaneously for 20 minutes with a keynote presentation of five slides, move into a 15-minute chat with a docent diving into research process and sources, and wrap up with the audience Q&A.

It can be tough to tour without the visible audience energy and the buzz of the book-signing table. Drawing in diverse attendees, historical organizations have reinvented the audience experience. Many have seen an instant uptick in engagement, which can translate into memberships, donations, and something many of us crave these days: a feeling of togetherness. Zooming through new technology training over the past few months, scholars in museums, libraries, and archives have turned to virtual book talks to build community, explains Angela Oonk, who runs The Clements Bookworm and is director of development at William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan. This means creating a scholarly home at each event that is welcoming to all. Oonk drafts a fun poll question to launch audience participation in each event chat. She offers presenters a dress rehearsal to double-check their slides. And all that prep works—people stay online for the live Q&A rather than waiting for a video to post, Oonk says.

Be open to a range of ideas about how we make history, and “think of it as a fireside chat.”

William Roka, Hamilton Education Program Coordinator at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and host of Book Breaks, has found similar success. Via StreamYard, Roka collects questions in advance on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. “It may seem simple, but calling up a viewer question, reading it aloud for the rest of the audience, and having the guest address it in real time helps to bridge the digital expanse between the guest and that viewer,” Roka says. “And, almost inevitably, we see viewers continue the discussion amongst themselves in the comments. We are even aware of a Zoom group that gets together after our programs to talk about what they learned during the stream.”

In tweaking your book talk for a virtual audience, a few final pointers stand out. If you’re Zooming, loosen up! Get comfortable with the virtual platform you’re using, just as you’d check the tech and seating setup before a conference panel. Meet with your host for a dress rehearsal, and practice screensharing your slides. Log in early to check your background, angles, and lighting. Tape up your bullet points behind the camera, Chervinsky advises, and be animated with your voice, facial expressions, and hand gestures. Reading directly from notes can cause viewers to click away. “I want to be able to look into that green light so that audience members feel like I’m actually looking at them,” Nelson says. Consider how WiFi wavers, so practice speaking slowly and clearly. Tell attendees where to buy your book, and drop a link in the event chat. Most important? Skip the stock talk, Ambuske recommends, and dig into crafting a real conversation about your work. Be open to a range of ideas about how we make history, and “think of it as a fireside chat.”

Are virtual book talks here to stay? Will all these Zoom stops translate into big sales? Like so many academic traditions recreated during the pandemic, it’s hard to know. But the fresh format does reunite authors and readers, inviting us to talk more about the curious and complex history of, well, everything. That’s all for the best.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.