As institutions transition to online instruction in the face of COVID-19, historians are struggling with what it means to teach history online. The AHA had planned to announce guidelines in June 2020 for online teaching in history, and we will continue to work to do so. In the meantime, we are publishing a series of short pieces in Perspectives Daily to help the many historians now working to navigate this emergency.

We offer these pieces with a few caveats. Much of what can be done quickly is not properly online instruction(courses envisioned for online or hybrid execution). Rather, for many, this is a rapid transition to remote instruction. Similarly, much of the advice depends on your own institutional circumstances; with regard to policy, particularly ADA policy, always defer to the rules of your home institution. Still, we hope these posts will help support student learning during these turbulent times, and we invite discussion of them and an exchange of ideas—both broadly conceived and narrowly practical—on the AHA Members’ Forum.

If you teach history at any sort of educational institution, whether K–12 or higher ed, chances are your institution has “pivoted” to remote (online) instruction, if not closed campus entirely, as a response to the rapid spread of COVID-19 and the imperative for social distancing. Over the past week, a wave of these pivots and closures has left many of us scrambling for alternative means of engaging our students in an online and likely asynchronous setting. This is not the optimal way to teach and learn history, given that good online courses take more time and planning to develop than the handful of days most of us have been given.

Lean Forward/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

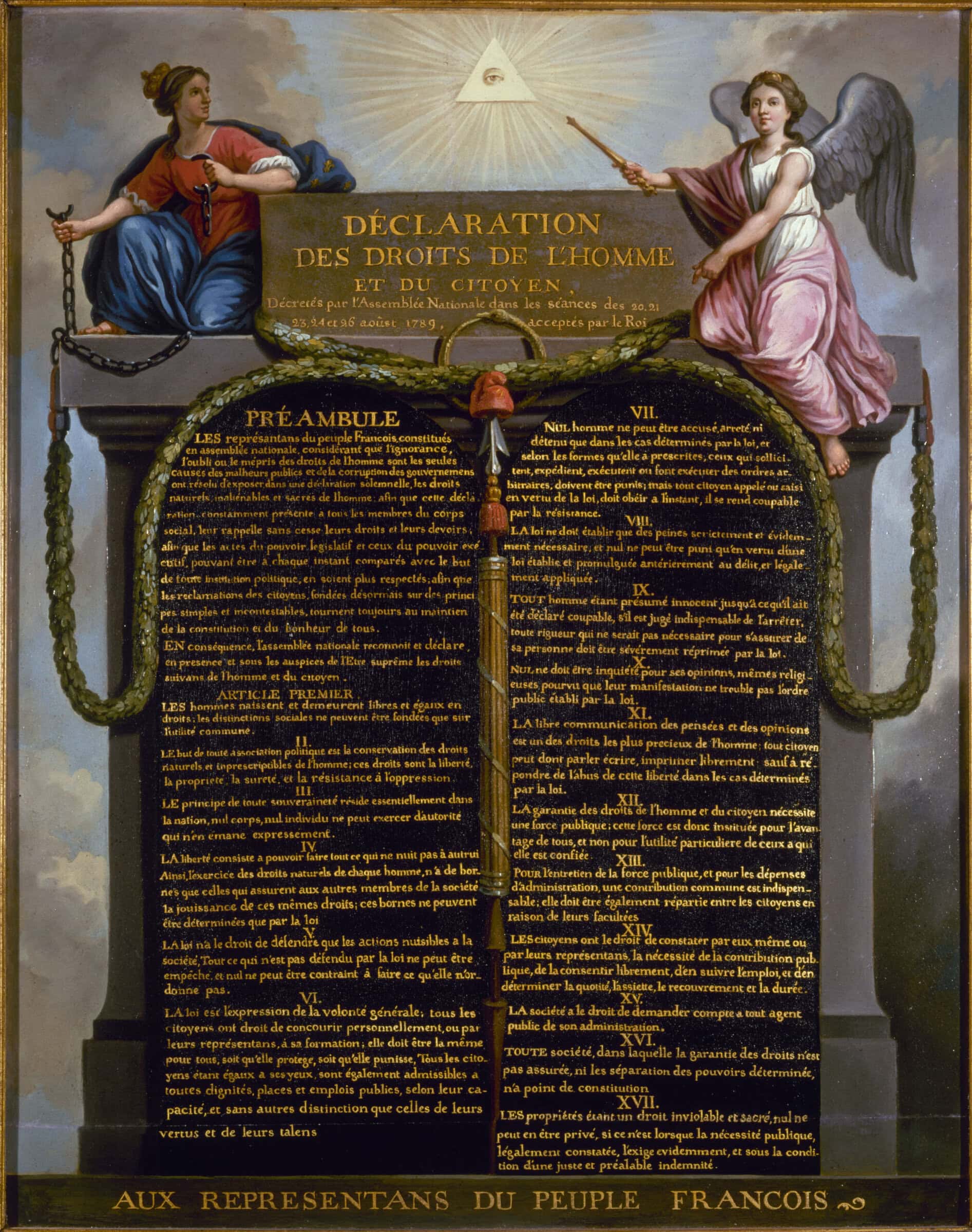

So what do we do? How do we keep as many of the essential elements of our course as possible, even if those look different online? We want to help our students to continue to be engaged with history; that is, to still feel present in the course and actively work with the course material. We want our students to do things like discuss, analyze, work with primary sources, and be able to communicate their interpretations to others.

Here I suggest a few basic tools you could use to promote those activities in an online course space. I’m writing for the novice online instructor, for those whose primary experience is in face-to-face classrooms where digital tools aren’t the primary mode of interaction. These suggestions may be familiar; if they are, great! Start with the tools with which you’re familiar and scale out from there. If these are tools you haven’t used, the hyperlinks direct you to overview pages or tutorial videos that can guide you through their setup and use.

- Google Drive (or another cloud-based file sharing system like Dropbox or OneDrive): Sometimes the simplest tools, those most familiar to both you and your students, are the best ones to use. Using the sharing features in Google Drive, students can collaborate on documents or presentations, peer-review one another’s work (you can comment on Google Docs just like you can in Microsoft Word), or upload media files to share. This starter guide from Yale’s Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning has great ideas and easy-to-follow steps for setting things up. Dropbox and OneDrive have similar capabilities; check with your institution’s IT Department to see if you have campus licenses and access to these services, and how you can use them via your learning management system (LMS) or campus network.

- Hypothes.is: Hypothesis is a web annotation tool that allows you to mark up a webpage the same way you would review and comment on a Word or Google Doc. It only works in the Google Chrome browser, but there are plug-ins to add it to your LMS and have students work on documents through that platform. Using Hypothesis, you could assign students an online primary source and they can leave comments, notes, questions, and links to other resources. It’s like a discussion board and document wrapped up in one. There is a well-curated page of tutorials, too; I recommend the quick-start guide for an overview.

- Video: Think about how content will present itself differently in this online environment. For example, a 50-minute recorded lecture might not be the most effective method (even if you’re a great lecturer). Consider “chunking” out material into 8–10 minute segments—lecture nuggets, if you will—and allowing students to view them in sequence on a more flexible timeline. Breaking up large swaths of content will help you to draw out important themes and continuities that could be the basis of a response paper or discussion. Once you’ve planned how you’ll chunk out your material, there are a few different video recording options you can use. If your institution uses a tool like Adobe Collaborate within your LMS, that might be the easiest route; your students are likely used to it, and you have institutional IT support for it. Many faculty already use Zoom, a videoconferencing platform that works easily through an extension for your web browser. You can conduct a “meeting” with just yourself (using the screenshare feature if you have slides or other visual material), record the session, and then share the link of the recording. You can also use Skype or Google Hangouts similarly—and all three of these video platforms have good mobile apps. If all else fails, use a smartphone, tablet, or laptop to record short segments of yourself in your office or in a classroom. Create a YouTube channel for your class (you can set it to unlisted to keep it private) and post your recordings there. This YouTube video (appropriately enough) walks you through the steps in creating a channel.

Many historians have already been doing this kind of teaching online, so there might not be the need for you to re-discover fire. Check out the #twitterstorians hashtag on Twitter to read and participate in ongoing conversations and resource sharing. Waitman Beorn, a senior lecturer in history at Northumbria University, has generously created a spreadsheet of teaching tools, digital history sites you can direct students to, digital tools for historical scholarship, digital humanities projects, and digital archives (use the tabs at the bottom of the spreadsheet to navigate between categories). H-Net has put together a repository for resources on teaching history online, which should be a thriving community soon. One of the most exciting cross-disciplinary products has been the “Keep Teaching” online community set up by the staff of Kansas State University’s Global Campus, an excellent virtual gathering spot where faculty, staff, and designers are sharing tips, tricks, techniques, and—most importantly—solidarity as we navigate this rapidly changing landscape together.

As historians and teachers, we pride ourselves on being able to engage students with the complexity and wonders of the past. Though our current circumstances are far different than we anticipated, we have the research skills and critical faculties to help solve this new set of problems. Being analytical and discerning about the tools we use is a necessary part of that process, but so, too, is our discipline’s remarkable willingness to collaborate and share expertise. If you’re one of the thousands of us “moving online,” good luck, and see you on the internet!

Kevin Gannon is director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning and professor of history at Grand View University, and a member of the AHA’s ad hoc committee on online teaching. He tweets @TheTattooedProf.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.