As I reflect back just a few short months ago to March, I am amazed at how quickly everything changed at my university. Within two weeks, faculty at my small midwestern college, Denison University in Ohio, went from expressing concern for colleagues in COVID-19 hot spots like Seattle and the Bay Area, to canceling conferences and other professional travel, to transitioning to remote teaching and saying farewell to our students for the remainder of the semester. In those two weeks every day seemed to bring a new major announcement from the college president or provost, sending us scrambling to redesign our courses, learn new technology, and—for those of us with children—figuring out how to accomplish all of this while homeschooling. As department chair during this crisis, I prioritized working on behalf of our department’s untenured faculty because COVID-19 had more serious implications for the careers of junior and contingent faculty than for those of tenured faculty.

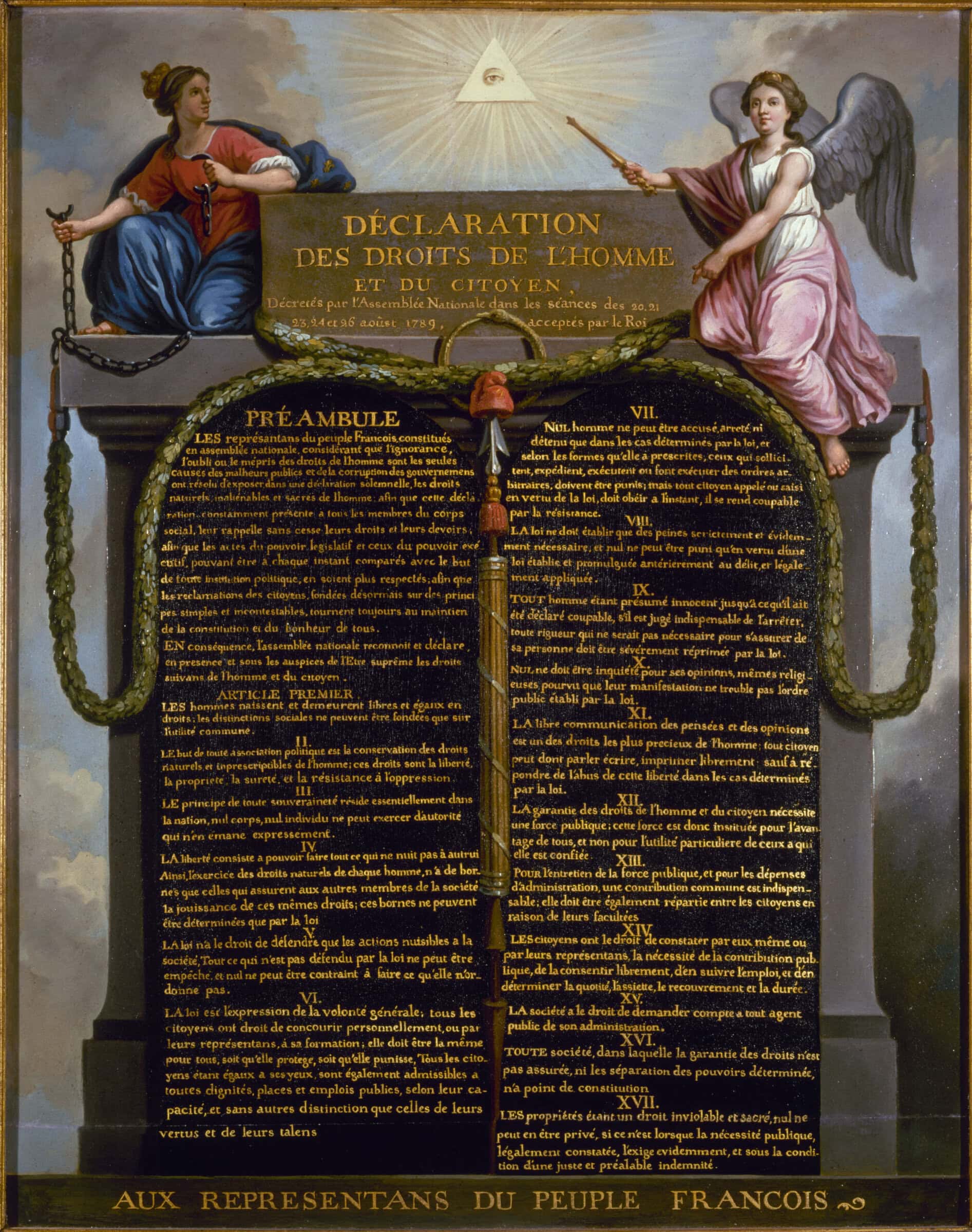

Lauren Araiza says that during COVID-19, it is important for departments chairs to support their untenured colleagues. PxHere Public Domain.

The most pressing professional concern for untenured faculty is their looming reviews for promotion and reappointment. Despite the volumes of scholarship documenting the inherent biases of student evaluations and legal issues with using a discriminatory tool in the review process, Denison and other teaching-focused colleges persist on relying heavily on them. Because I am a tenured faculty member, student evaluations no longer determine my professional success. But as chair, I have a responsibility to help untenured faculty successfully navigate their careers. I believe that preventing the use—and abuse—of student evaluations during the pandemic is crucial to the success of untenured faculty. My concern (shared by many others) was that students would use their evaluations to express their discontent with the transition to remote learning in general and the university’s overall response to the pandemic. Knowing that this would make an already stressful situation worse for untenured faculty, I pushed the provost to consider suspending evaluations for the spring semester. Ultimately, the university decided to collect them but let faculty decide if they will be used in reviews.

I prioritized working on behalf of our department’s untenured faculty because COVID-19 had more serious implications for the careers of junior and contingent faculty.

As chair, I see myself as the department’s liaison to, but not a part of, the administration. In turn, I serve as the administration’s translator back to the faculty. In the first few days after Denison announced that we would transition to remote learning, the faculty received several conflicting messages. On one hand, we were instructed to adhere to the course schedule and maintain the university’s credit hour policy. On the other hand, we were told to be flexible and accommodate our students’ needs. As confusing as these messages were for me, I realized that they would be much more stress-inducing for untenured faculty who believe that closely adhering to university policies was essential for successful reviews and reappointments. I remember clearly how, as a junior faculty member, the support of my senior colleagues was essential to alleviating uncertainty and self-doubt. As chair, I wanted to assuage my colleagues’ confusion and concerns. I therefore sent a simple email to my junior and contingent colleagues that basically read, “Whatever you’re doing is great. It’s up to you whether you teach synchronously or asynchronously, what tools you use, and what pedagogies you employ. However you decide to teach is fine with me.” As chairs, one of the most important things that we can do is to let our untenured colleagues know that we are in their corner, even—or especially—if it means that we are in conflict with the administration.

The chair’s role is also to raise important topics on behalf of their colleagues. Denison is a small liberal arts college with approximately 220 members of the teaching faculty. This small number means that just about all the faculty know each other (at least by name or sight) and the senior administrators know all of us. This contributes to its often-touted sense of community but can also be intimidating for untenured faculty who sometimes feel like they are constantly being evaluated by their colleagues, which can have a silencing effect. Something chairs can do is leverage our positions on behalf of untenured faculty and ask questions of the administration that push issues with their needs in mind. For example, scholarly productivity during this period has been of heightened concern to all faculty, but especially for junior faculty. The nature of the pandemic and the attendant restrictions has limited our ability to conduct archival research and lengthened publication timelines. These challenges are compounded by the time necessary to redesign courses, learn new technologies, and care for loved ones. In conversations with administrators and fellow humanities chairs at my university, I have pushed for both clarity and flexibility regarding university expectations for scholarly productivity.

As chair, I see myself as the department’s liaison to, but not a part of, the administration.

The Denison history department has argued that official language needs to be added to the faculty handbook so that faculty are not penalized in the future for being less productive as scholars during this time. When talking to administrators I made it clear that although the pandemic has completely undermined my research agenda, my concern is for untenured faculty who are expected to publish to be reappointed and promoted. From talking to my untenured colleagues, I knew that some of them did not feel comfortable asking administrators and senior colleagues about allowances for scholarly productivity, lest they be judged for failing to find a way forward. I therefore use my position when I can—and when untenured faculty need—to give them a voice. (After I became chair, I was at a cocktail party with many of my faculty friends. One of them asked how being chair had changed me. Before I could answer, my husband said, “She’s gotten mouthier.” He wasn’t wrong.)

Serving as department chair during the advent of COVID-19 presented many challenges. I attempted to stay connected with my department colleagues and maintain a sense of community (we even managed to have a lovely, virtual sendoff for a colleague who retired in the midst of all this madness). I kept everyone informed of new developments at the university and tried to be a resource for our majors and minors, newly admitted and prospective students, and colleagues. But I am most proud of the work that I did on behalf of the junior and contingent faculty in the department. Chairs can use our positions in myriad ways to help our untenured colleagues and friends feel secure and be successful, even in times of crisis.

Lauren Araiza is associate professor and outgoing chair of the department of history at Denison University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.